North American Cover

Rising Zan: The Samurai Gunman opens with one of the most memorable theme songs in any video game. It’s unique to the North American and PAL releases; rather than attempt to translate the original Japanese song, modeled after heroic themes for classic tokusatsu shows like Kamen Rider, two of the American voice actors wrote and performed their own country-rock song. Entitled “Johnny no More”, it sets the game’s story in just a few lines. It takes place in the Wild West, and it’s about a blue-eyed boy who dreams of being a hero. After being defeated by a ninja assassin, he leaves for Japan to learn to use the sword under the tutelage of an old master. A few years later, he returns, half-cowboy and half-samurai: he’s not Johnny anymore, but Zan, and demands that everyone refers to him as such. He also believes that he’s sexy.

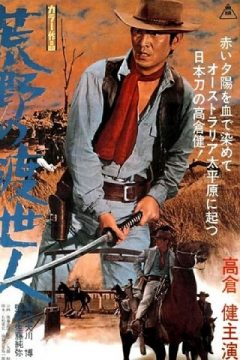

Sexiness aside, this is not an original idea. Westerns and samurai movies inspired each other back and forth throughout their history, and the idea of combining the two emerged decades before this game. As early as 1968, Japanese studio Toei, better known in the West for their anime division, released The Drifting Avenger; shot in the Australian outback with a cast of locals standing in for Americans, it starred Ken Takakura as the son of a samurai who sets out to avenge his family after they are slain by bandits (his father is played by Takashi Shimura, co-star of The Seven Samurai, easily the most famous samurai movie outside of Japan). Finding his katana maladapted to the Wild West, he learns to use firearms from an older gunslinger before going after his enemies, like a mirror image of Rising Zan‘s Johnny. Several other movies would continue this Ancient-East-meets-Old-West tradition in the following years, including one literally titled “East Meets West” in 1995, just four years before this game.

The original samurai gunman

But the Japan from which Zan‘s foes and sensei come from isn’t just Japan; it’s wacky-Japan-as-seen-by-Westerners-long-ago, full of mystery and strange inventions. That isn’t an original idea, either; that conceit is central to the Tengai Makyo/Far East of Eden RPG series, down to referring to the country as “Zipangu”. Similar depictions of Japan are not uncommon in anime, manga, film and video games (Konami’s extensive Goemon series being another prime example of wacky feudal Japan).

At the very least, Rising Zan is the first to bring these things together within the medium of videogames. More significantly, its gameplay plays as a rough prototype of most 3D sword-based action games from the PS2 on. You’ve got a basic sword attack chain, and special moves that can be chained together with them, in a limited fashion. The moves use a gauge that refills automatically at a pretty rapid pace. You’ve got a gun with unlimited ammo that does less damage but obviously has more range; there’s a special move for it that’s probably the coolest attack in the game, and an attack chain that combines sword and gun. You can block, but you still take chip damage, evade attacks with a sidestep (or occasionally, a jump), and deflect projectiles back at your foe. It’s all there already, none of it as good as it would soon become.

Though some of those games feature adventure elements, Zan is pure arcade action. This is a game that wants to be exciting all the time. You spend more time fighting midbosses than “regular” enemies. Time limits always seem to be popping up, forcing you forward. Traps are everywhere. When you’re not trying to break down random pieces of machinery while dashing around to avoid both floating balls of spikes following you from above and a rotating fire cannon, you’re given 15 seconds to free all the prisoners from cells inside a train wagon before it explodes. Make it through that wagon, and you suddenly find yourself ducking and weaving through security lasers coming out of the walls like a sophisticated diamond thief in a heist movie. At various moments, you come across All-Button Events, which is what the game calls it when it wants you to mash every button on your controller in order to hurl a giant bomb back at a half-naked ogre or push a man named “Push-man” into a wall so hard that his head comes off. Because it is a video game from the 1990s, there is a mine cart sequence. Of course, it’s really a crazy rollercoaster ride, and you have to jump and block and shoot your way through it, until you face off with what may be a living train. Put together roughly 10 minutes of such setpieces in a nearly completely linear succession, add a “real boss” at the end of each stage, plus about a million in the final two, and you’ve got a game.

It’d be one long, zany rush of adrenaline, if it weren’t for all the technical flaws. Nearly every early 3D game has been described as having “awful cameras” at one point or another, but it has rarely been as true as it is here. The camera does a particularly bad job of following you as you move, and the only form of manual control you have over it is the L1 button, which is supposed to turn it to the direction you’re facing. But it’s capricious. The camera will continue to move for a second or two after you do; as long as it’s still moving, L1 will not work. It’ll also refuse to work if you happen to be standing in a spot it doesn’t like; sometimes you’ll get an “error”-type sound effect so you know to move a bit and try again. Sometimes you get nothing. At time, you’ll get into a corner and the camera will go crazy, moving left and right in a frenzy of unfixed buggy programming. And sometimes it’ll inexplicably pull a 180 on you in the middle of a fight, suddenly hiding your enemy from view. This isn’t a horror game; there’s no excuse for any of this. The only relief comes in the form of the lock-on button; as long as you’re locked onto an enemy, the camera will usually try to keep both Zan and said enemy on-screen. This is particularly efficient during the countless boss battles, though even then, things will still go wrong on occasion for whatever reason.

It isn’t much help when facing weaker enemy waves, which tend to surround you, or bosses that like to warp around, losing your lock-on in the process. For the latter, the game actually provides something like a small radar in the lower-right corner of the screen that can come in handy. When it doesn’t work, you can always just run circles around the room until you come across the boss again. There’s no good solution for the weaker enemy waves; your spinning sword attack will dispose of weakest, while the strongest of them will be a pain to deal with no matter what you do.

That’s not all. For all his training, Zan’s swordplay is slow and clumsy. The first attack tends to miss because it has so little range, and the attack animations take too long for the fighting to feel responsive. At least you can cancel them by blocking, though no fast enough to do anything with it beyond actually blocking. The visual feedback for hitting weaker enemies is a bit lacking at times, too. The bosses and midbosses that you spend most of your time fighting have visible health bars, so it’s less of a problem, but it makes the weenies even more unsatisfying to fight.

There’s also something called Hustle Mode, which is triggered by using a gauge that fills up as you kill foes. In Hustle Mode, your attacks are much faster and your sword much longer. You also move like you just found all the Chaos Emeralds, so it’s even more essential that you remain locked onto your enemy if you’re going to be able to do anything.

You can restart a level as many times as you like when you die, and the game can save the last level you reach so it’s accessible from the start menu. If you train long and hard – as hard as Johnny trained to become a samurai gunman, maybe – you’ll eventually be able to tame the cameras and controls, but the amount of frustration it takes to get there is greater than the amount of excitement the game has to offer.

They caught the programmer in charge of the camera routine

Among all this bad execution, there are some amusing touches and clever ideas. During the cutscenes, the American characters speak English, while the bad guys from Zipang appear to be speaking gibberish (with English subtitles); listen closely, however, and it turns out each character is just repeating one particular Japanese word over and over, usually with some connection to their character. The geisha is saying “kimono”, while the sumo wrestlers repeat “chanko” (chanko nabe is a protein-filled stew sumo wrestlers eat to gain mass and strength). Sometimes, they’ll get mad and swear at you, and one repetition of the word will get bleeped out. One level has you playing through minigames to rescue hostages; in one of them, a giant Lucky Cat statue lobs bombs at you that you have to bat back with your sword, while another has you shooting at a slot jackpot machine to force the jackpot that’ll open a door. Fun ideas, but the timing on both minigames is too strict, considering they’re not optional. One level, run by a kabuki actor, has you going from one theater set to another, fighting a different boss in each set.

There’s very little to the story beyond the premise. The villains constitute an organization named Jackal; they showed up one day to kill innocent folk and steal their gold. That’s about it. They sometimes refers to people as “humans”, so some of them may be robots or aliens. It’s not too clear. Despite the cartoon silliness of it all, death is dealt downright casually in this game, by good and bad guys alike. Zan doesn’t just beat his enemies and let them come back another day like so many video game heroes of the era. “Can’t you just kill them all?”, asks a former neighbor after recounting how those comical goofballs from the cutscenes murdered her entire family. “No problem, ma’am”, he replies. And he does.

One of the characters that (barely) appears in the cutscenes is a female ninja named Sapphire. The game doesn’t say so, but according to the manual, she’s the daughter of Suzuki, the old master that trained Zan (Suzuki, by the way, is voiced by Charles Martinet, the voice of Mario). Finishing the game unlocks her as a playable character. Instead of a gun, she throws shuriken, and she has fewer special moves, but she’s much faster, which generally makes her easier and more fun to play as. She should have probably been available from the start.

The developer, UEP Systems, had started out a few years before with a snowboarding game, Cool Boarders. The sport’s popularity was growing then, and the game was a surprise hit. After a first sequel, they sold the American rights to Sony, who had an American developer continue the series in the West. Meanwhile, UEP continued to make Cool Boarders games in Japan, some of which were released in America under alternate titles. Their entire history consists of snowboarding and skateboarding games; Rising Zan was a complete outlier. For whatever reason, UEP began bankruptcy proceedings in 2000, a little over a year after Rising Zan was released. The game’s director, Makoto Sunaga, founded Studio Zan in 2004, which reinforces the impression that the game must have been his passion project. His company handled the game’s later PSN release, and is still active as a contract developer working under larger companies. The other two planners (or game designers, if you prefer) joined Namco and Koei, respectively. Though it never got a sequel, its setting often draws comparisons to Samurai Western, a spin-off of the Way of the Samurai series released a few years later for the PS2. While that game also has a sense of humor, it’s a much more straightforward hack-‘n-slash gameplay-wise.

With its catchy theme song, offbeat tone and setting, and excellent title, Rising Zan: The Samurai Gunman is a more interesting game than many. And if it did influence later games like Devil May Cry, Onimusha and the like, then it even has some historical significance. If it were just more polished, better realized, it may have become the cult classic it seemed destined to be. But it isn’t, and it didn’t.

Links –

Mobygames – Game Credits