It’s rare that a game comes along packed full of new ideas, trying something very different for the first time, even if not all of the ideas come together perfectly. But such games can be some of the most refreshing experiences the gaming industry has to offer, and nowadays, they usually come from the indie scene.

Road 96 is one of those indie games. In some ways, it fits neatly into the genre of story games such as Life is Strange and the Telltale games. In others, it innovates with enough new ideas that it feels unique and in some ways unlike anything else out there. Like any experimental idea, it has its flaws, but it also does some things very well.

Road 96 is about a road trip. Multiple road trips, in fact, as you play the role of multiple randomly generated teenagers who are trying to flee a fictional country named Petria. Each trip eventually ends in some form: either escape, arrest or death. Once that happens, another trip with another randomly generated teen begins, etc. until eventually the final trip is completed, and the player gets to see which of several endings they’ve earned. Trips are divided into a handful of chapters chosen at semi-random, and many of those involve interacting with at least one of the game’s major characters in the story.

Characters

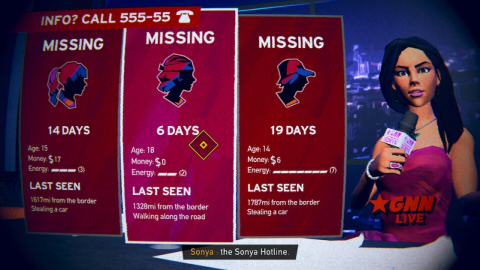

Sonya Sanchez

Petria’s biggest celebrity, a TV and radio shock jock who supports President Tyrak.

Zoe

A teenager who ran away from her wealthy home.

John

A friendly, strong and stocky truck driver who’s also a member of an extremist group.

Alex

A teen genius hacker who builds computers and creates his own video games.

Stan and Mitch

Two stupid robbers who love to brag about their crimes.

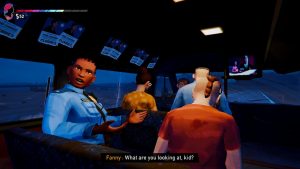

Fanny

A police officer who is conflicted about her job.

Jarod

A taxi driver with major anger issues and an itchy trigger finger.

President Tyrak

The dictatorial president of Petria, willing to do anything to keep control over his country. He’s a polarizing figure who is loved by his supporters but hated by many others.

Lupe Florres

Tyrak’s opponent, running for president on a platform of change.

There is also a group known as the Black Brigades. Their symbol is sometimes tattooed on the arms of its members, and shows up as graffiti sprayed on walls where supporters congregate. They oppose Tyrak, but they disagree about tactics. They play a major role in the story.

You control your character in a first-person perspective, with only a silhouette in the corner hinting at what your current character looks like. You can walk around and click on floating commands to interact with things, or click floating dialog choices in conversations. The areas where you walk around are often pretty interactive, with food to eat, money to steal, posters to vandalize, doors to break into, secret areas to discover, documents to read, cassette players and radios to play, and more. And you can gain or lose money or energy. Running out of energy results in passing out and being robbed or arrested. And actions you take affect later chapters and the ending.

If this sounds a bit tricky to understand, here’s an actual chapter used as an example.

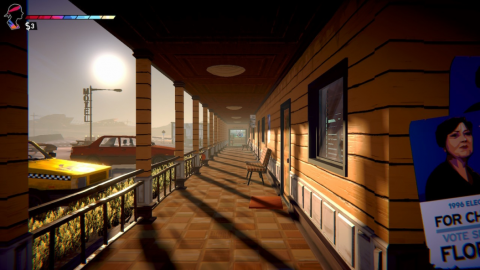

In one chapter, you come across a two-story motel. There are posters for Florres everywhere, along with Black Brigade graffiti. Cars driving by blast slogans for Florres, Tyrak, or both, depending on each candidate’s current standing in the polls. A pay phone allows you to call home for a dollar.

Walking around, you can overhear what sounds like terrified muffled yelling behind one of the doors on the second floor. On the first floor, a door to an empty room can be entered if you’ve previously earned the “pick locks” ability. Doing so leads to what appears to be just an empty room… unless you notice the lamp that can be tilted to discover a secret room. Inside that secret room is a letter on the table. The letter appears to be written by a father to his adult child, explaining that the father is being stalked by someone. Could this be the same man who is heard making muffled noises upstairs, as if bound and gagged?

All of that is optional, however. Instead, to progress the story, you must go to the motel’s front desk, which triggers a scene where Fanny, a police officer, enters and asks for your help. Her rationale is that this is Florres territory, and the people there are Black Brigade supporters who hate police, so she’ll need a teenager to avoid suspicion and ask people for information on a suspected terrorist. She gives you a chart containing a bunch of faces to cross out, and you essentially play Guess Who? by asking people for information on the suspect. This gives you an opportunity to be truthful or lie to Fanny. Before you return to Fanny, the motel manager begs you not to tell Fanny the truth, saying that police are the enemy.

After you give Fanny either true or false information on the suspect, she receives a phone call which you overhear. Shortly after, Fanny then rewards you with some money for your help, and you can then choose your method of leaving the area by walking up to and choosing the appropriate symbol: hitchhike, walk (which uses energy), take a taxi (which costs money), take the bus (which costs more money), or steal a car (if you managed to find a randomly spawning key).

That’s an example of only one chapter. Each chapter has its own unique characteristics, including gimmicks such as playable minigames including Connect Four, air hockey and even video games. Some chapters have situations with other characters which result in a “tension” or “anger” meter appearing, which triggers something bad if it gets full. Sometimes making the wrong choice can result in either you or other people being killed or arrested.

You never know what will happen next, whether it’s being asked to operate a camera during a stakeout, help two robbers carry out a heist, or help someone make a difficult phone call to an estranged family member by suggesting what to say. Most chapters contain opportunities to influence the direction of the country, characters to talk to, and more traditionally video gamey elements such as things that can be purchased or collected, or secret areas to discover which sometimes contain additional plot-related elements.

You can even earn special abilities such as lockpicking, a permanently extended energy meter, and a government ID that you get to keep between characters. There are things you might not be able to do yet, due to lacking a needed ability or item, or not having enough money or energy, forcing you to plan things out ahead of time if you want more options available later. Eat food now to get more energy, or save money in case you need to buy something useful later?

Your choice of how to leave the area influences which chapter occurs next – as some chapters take place inside buses, cars or taxis in which you cannot move freely around but can still look at details and try to find hidden items such as money, while others take place in areas where you can walk around and explore. One consistent feature is that you’ll never encounter the same character twice on the same trip, with some story-specific exceptions. All the chapters may seem disconnected at first, but it’ll eventually become clear that characters connect to other characters, and everything connects to a bigger story.

Player choices such as vandalizing Florres or Tyrak posters, stealing money, and eating rotten food, all influence the direction of the country as well as your “karma.” Tyrak gains more supporters if you go on a shameless crime spree, so while you do need money to buy food, and food in order to live, whether or not to steal is a choice that should be measured carefully. There are ways to earn money that don’t involve stealing, and sometimes they can be even more lucrative. There will even be times when the player is asked to do something for a person, such as film someone on camera. Deliberately not doing what you’re supposed to (in this case, pointing the camera at other important things instead) can also impact the story.

Eventually, at the end of a trip, you will reach Road 96. Road 96 leads to the border of Petria, where after spray painting a slogan from a list of several choices, you can attempt to escape through one of several means, each of which is closed off for the next trip, forcing the next refugee to try a different tactic. You can also choose to leave money behind to help other people who are trying to escape. When the next trip begins, a news report by Sonya will dishonestly describe what happened in the previous trip, the current polls will be shown so you can measure the direction of the country and likelihood of getting the desired ending, and the next playable teen can be selected from a random group.

Road 96 runs on video game logic, of course. Why does it only take about a half dozen hitchhiking teenagers to dramatically influence a country’s election or desire for revolution? Why does spraying a slogan in a cave cause even a single percentage point change in the president’s approval rating? There’s a logic behind why stealing money from people increases those people’s chances of voting for Tyrak, the “stability” candidate (who, quite frankly, doesn’t have a very stable country under him), but the effects of roughly six teens on the entire country are pretty exaggerated.

And for that matter, why do so many characters want to dump their personal lives and deepest secrets on random hitchhiking teenagers? Or ask them for advice on what to say in phone conversations? And there are the conversation choices which have symbols next to them representing voting, protesting and fleeing. Choosing these magically affects the polls. Does that mean you swung one million votes with a brief conversation with a truck driver? At least it makes sense that you can swing the polls by filming live police corruption instead of what you’re asked to film.

The video game logic extends to the location itself. The dystopian country of Petria is inspired by real world locations such as North Korea, the United States, and the Middle East, and isn’t directly analogous to any real country. Petria appears to be an oil-rich predominantly desert nation of roughly eight million square miles, which uses dollars as currency, has a voting age of 14, ten-year presidential terms, limited entertainment choices, exists in some hybrid of the 1980s and 1990s, and leaving the country is criminalized except under special conditions.

It’s also loaded with corruption galore, including the police force. Its dictatorial leader is popular with a majority of the public, and many of his supporters are cruel, especially to teenagers trying to flee the country.

Road 96 has a very fleshed out setting and atmosphere. Characters often reference other characters or events in the story, including things you did on a previous trip. Many people have opinions on what’s happening in Petria, and aren’t shy about expressing them. Tyrak and Florres supporters often put their posters up on walls or in their cars, making it very clear which way they lean, while some people are apathetic or apolitical. Even the people who hate Tyrak are divided on whether or not Florres will be a good replacement.

Televisions are frequently playing the Sonya Show. Vans adorned with Tyrak and Florres banners drive by blasting election slogans. You can even call any phone number that exists in the game and discover some secrets. Everything in the game world ties into its story, themes, or even reveals additional information on its characters. Even hidden areas such as caves, locked sheds or abandoned vans which sometimes contain notes and letters referencing events in the story, or the personal lives of characters who are affected by the events in the country.

Due to your choices, later chapters can actually change to feature more protests, and more or fewer Florres or Tyrak signs or Black Brigade graffiti. It might take several playthroughs to notice these differences, but the same chapter will not look the same every time. Even the location of a chapter can be different, such as a drive taking place on a winding mountain road instead of on a flat road, or a burger joint being located near the woods instead of in wasteland. Keys used to steal cars have a low chance of randomly spawning.

Many characters have hidden depth that becomes apparent as you encounter them repeatedly across additional chapters, or meet other people who know them. Characters who do immoral things sometimes have good reasons for doing them. Some people are regretful about their past. Every character has some connection to at least one other character in the story. And despite the core story involving life in a totalitarian nation, everyone has their own uniquely personal problems, which are directly affected by the country’s problems.

Another thing that might be surprising, given how tense the game’s atmosphere can be, is the amount of humor in the game. Even with the serious dystopian theme, there’s quite a cast of eccentric characters. Alex spits off some mad outdated slang, dog. Stan and Mitch, the goofy robbers have endless enthusiasm, chaotic energy and a willingness to pal around with and sometimes hire teens for their crazy schemes. Zoe dresses punk but plays the trombone. And Sonya Sanchez is the kind of character some love to hate.

Not all of the semi-randomly chosen chapters will play during a single playthrough. If you complete the game once and see an ending, there will likely be more chapters you haven’t seen yet, which you’ll have to discover in a second or maybe even third playthrough. In fact, the loading screen shows a percentage for each major character, representing how much of their story you’ve played through, making it clear if there’s more to discover. Since some chapters take place in vehicles and others involve freely walking, it’s a good idea to diversify your method of travel to experience as many as possible.

One thing that works in this game’s favor is its pace and relative brevity. Conversations are typically short and to the point, often giving a character a chance to make a statement, and you usually aren’t able to ask multiple questions – pick one of the choices and that’s all you get this time. Longer conversations are generally the story-important conversations, and they’re not super long. A full trip typically takes between 50 and 75 minutes, and the number of trips needed to reach an ending is typically from five to seven.

At the same time, there is one thing holding back the game’s replayability. Like so many other story games before it, Road 96 has many choices that seem like they’ll affect the story, but things will conveniently play out in a very similar fashion anyway. Did you refuse to rescue this character? That’s okay, someone else rescued them, though trying does raise karma. There’s a lot of that, where something that seems like it should majorly affect the story instead only slightly swings the polls/karma.

Speaking of the ending, it’s divided into segments that are separately influenced by different factors, such as whether or not certain characters lived, how you interacted with specific people, and finally, the polls and karma. It would have been better if the ending had more segments that could be influenced in more ways, to truly create even more replay value and make your choices feel like they matter more. Instead, Road 96 succumbs to the most common flaw of story games – being railroaded into where the story wants you to go, with only a few things truly changing in any meaningful way, and most changes just being cosmetic or involving new dialog.

Which is a shame, since this game has so much interactivity. Replaying the game and seeing the changes in the world that occur as a result of your actions helps bring the world to life in a way that goes beyond atmosphere alone. The use of money and energy, the ability to die, the ability to influence what chapter comes next via how you choose to leave the area, and the randomization, are all innovative features for the genre. As it is, Road 96 is an imperfect but unique experiment that some will love and others may find intriguing, and an example of how to innovate in story and adventure games.

Finally, a word on content, for those who might be wondering if this game is appropriate for their kids. The cartoon graphics, humor and lack of excessive “big words” help make the story and its themes approachable and easy for kids to understand. Dialog sometimes contains mild profanity, with heavier profanity replaced with shorthand (e.g. “A-hole” and “F-in”). There’s the occasional mild sex joke which is written in such a way that it’ll go over nearly all kids’ heads, and there’s some alcohol use and portrayals of drunkenness, which is always portrayed negatively. And while characters die, there is no blood.

Road 96 deals with adult issues without feeling like it’s throwing around “adult content” for the sake of doing so. It’s not posturing at being grown up just to grab a higher age rating, but is actually mature enough to not overdo things. Even for adult gamers playing it for themselves, that can feel refreshing. And with the themes its story tackles, such as political polarization, poverty, corruption, cover-ups, revenge, media bias and the correct way to fight against an unjust system, the game can feel both timely and timeless.