Exclusive titles are the backbone of a console’s legacy, and they should ideally bring something noteworthy to the table. While the Lynx’s handful of exclusive titles don’t get much in the way of recognition, they all made a strong effort to try and provide the underdog console with interesting games even in the face of stiff competition. Robo-Squash, developed and published by Atari Corporation itself in 1990, was actually something of a trailblazer among the Lynx’s early lineup. It was the second sports title to appear on the Lynx, one of the first games to make use of the ComLynx cable for multiplayer, and it was even an early example of the Lynx’s notable pseudo-3D graphical abilities.

Robo-Squash was developed by a team of four people: Ed Schneider was the programmer, Robert Nagel handled the artwork, Craig Erickson is listed as the game’s producer, and David Tumminaro is responsible for the game’s two music tracks along with its sound effects, though he is strangely uncredited within the game itself. Three of the four team members previously worked together on 1989’s Whitewater Madness (the first title for the Atari STE model computers) and would go on to help create the Lynx ports of Hydra and Roadblasters, two titles that make excellent use of the Lynx’s pseudo-3D and sprite scaling capabilities.

It’s a shame the story isn’t a prominent factor in the game because what’s on offer in the manual is delightfully absurd – in the 31st century, the president of the world has died, plunging the United World Federation into chaos and leaving a rift between the “World Party” and the “International Party”, the two groups at the forefront of power. As a representative of the World Party, your goal is to settle the dispute between the two parties by winning games of Robo-Squash and prevent the International Party from dividing the world back into the nations of the 21st century. In the game itself, all you get is a brief text introduction via a computer before the game starts and an even briefer ending should you win the competition.

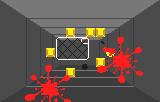

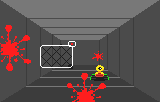

While the game’s title makes it clear that traditional squash is used as a foundation, several liberties are taken with the concept, resulting in more of an amalgamation of Breakout, Pong, and squash. Instead of playing next to one another on the same court as in traditional squash, competitors are instead placed across from each other with a wall of bricks between them. A game of Robo-Squash has two possible win conditions: get the ball past your opponent three times, or destroy all of the bricks and then hit the yellow spider that appears in the court before your opponent does. Once the ball is served, players can move their paddle around the screen in order to hit the ball and angle their shots based on where the ball hits their paddle. The ball increases in speed as it gets rallied back and forth in order to make things more intense, though the speed caps at a certain point depending on the difficulty chosen. If a player misses the ball, their screen will get splattered by the ball, obscuring part of their screen and creating additional pressure as they now need to deal with more restricted vision for the rest of the match. This is a great idea when playing against another human, but against the AI it’s nearly impossible to tell how much they’re actually being affected by it, if at all.

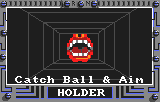

The pseudo-3D perspective makes aiming take some getting used to, and using a directional pad to move around in eight possible directions can be tricky since movement can feel somewhat sensitive. Luckily, there are four possible power-ups per round that can help you turn the tide of a match. The shooter power-up allows you to shoot projectiles to destroy bricks and even other power-ups, with the ensuing explosion leaving behind a cloud of smoke that can hide the ball. While clearing the field faster and preventing your opponent from getting other power-ups is very helpful, it comes at the cost of earning fewer points per brick. The Holder lets you catch the ball each time it comes back to you, letting you re-serve the ball and aim wherever you wish. The Expander is probably the least effective power-up of all, as the increase in paddle size it grants you is somewhat difficult to notice. Last but not least, the Spotter shows you exactly where the ball is going to land, so returning it is a simple task. All the power-ups look vastly different (the Holder is a pair of lips and the Spotter is an eyeball, for example) and they constantly animate in a way that’s more charming than the icons or letters that power-ups are commonly depicted as in other games.

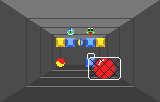

Between matches, players are greeted with a screen showing 16 spheres arranged in a 4×4 grid. The winning player gets to select a sphere, which determines the arena that the next game will be played in. Should a player win enough games to fill out an entire row or column of spheres in their color, they’ll be rewarded with a big point bonus, giving the game a second layer of strategy that’s very much welcome. Once all 16 games are played, the final scores are tallied up and the player with more points is declared the winner.

This structure gives Robo-Squash a unique sense of flow compared to other sports games, but it ultimately makes the game feel drawn out. The only difference between each arena is the arrangement of the bricks and power-ups, so they all look identically drab and play out the same way. Additionally, the AI is very adept at keeping the ball in play even on the lowest difficulty, so matches can drag out to the point where it feels like hitting the spider is the only reasonable way to win. Simplicity is ultimately Robo-Squash’s greatest strength and biggest weakness – the simple rules and tight mechanics make it easy to jump in for quick sessions on a hypothetical commute, but the sheer repetition makes the game fail to engage long-term in favor of more substantial experiences on the Lynx with concrete endings and goals to achieve.

Once the days of Pong consoles in the 1970s were over, squash adaptations became exceedingly rare in video games, so it’s a pleasant surprise to see one of the Lynx’s earliest titles represent the sport. In the following years, other developers would go on to adapt squash in interesting and ultimately more successful ways. Just a year later, Sega’s Twin Squash would use a similar concept of combining squash with Breakout to greater effect thanks to a livelier presentation and more variety. Gaelco’s 1992 arcade game, simply called Squash, offered a much more accurate and authentic take on the sport. The Virtual Boy’s Space Squash also used a sci-fi approach, but offered a wider range of opponents, more gameplay mechanics, and a sense of progression to keep players engaged.