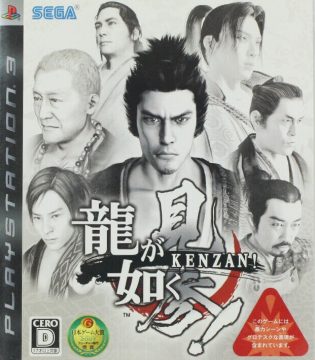

Before making a proper sequel, the RGG devs decided to make a spinoff to get used to the tech on the PS3. The end result was Ryu ga Gotoku Kenzan, taking place in ancient Japan, with little to do with the main series apart from featuring many of the same mechanics and characters – or rather feudal approximations of them. What makes it especially interesting is that this side-story is also a reworking of the classical novel Musashi, by Eiji Yoshikawa, which was in turn based on one of Japan’s most revered and skilled swordsmen. If you want a cheap analogy, imagine if all the actors from the first two Godfather films came together afterwards and reprised loosely equivalent roles for a radical reimagining of the Robin Hood fable. It’s that degree of strange and awesome.

This sort of thing is not without precedent. The early Yakuza games are often compared to the Kunio-kun series (more widely known under the River City moniker for English speakers) in the way they compared open-ended RPG exploration with beat-em-up action. The Kunio-kun series took a similar route with the Famicom game Downtown Special: Kunio-kun no Jidaigeki da yo Zen’in Shuugou!, which similarly recast all of its modern day characters in the roles of their feudal forebears.

It should be noted now that the story of Kenzan is complicated, weaving itself between real historical events and characters, plus characters from previous games. To full appreciate its epic scope, it’s worth taking the time to read up on various subjects. Thankfully FAQ writer Patrick Coffman has made an exceedingly excellent guide for Kenzan, available through GameFAQs, which not only acts as a frighteningly detailed game guide, but goes to great trouble explaining the story’s intricacies. Even without knowledge of Japanese, having the guide explains everything, and so where applicable we’ll quote Mr Coffman directly. There are also various YouTube video guide to help English players with progressing through the game.

The story actually differs a fair bit from Musashi (see section on the novel itself), with series stalwart Kiryu taking on the role of the eponymous Miyamoto Musashi sometime around 1600. As a renowned swordsman and instructor, Musashi is headhunted by military man Marume Nagayoshi for a secret mission for the Tokugawa clan. At the game’s start, Musashi is showing his students a style of sword-fighting which wields two swords, and which Nagayoshi is impressed by. The secret mission is meant to take place just before the real historical battle of Sekigahara, which marked the end of the Sengoku era in Japanese history, unified the country under one ruler and ushered in the Edo period.

Coffman: “It is important to note that the end of this era was a time full of treachery and betrayal. It was an age when military might made right. This, we are to believe, was the day of the swordsman, or ‘kenshi’, which is one of the main themes in the game.”

During the secret mission Musashi (Kiryu) meets Majima Gorohachi, aka Shishido Baiken from the novel. He’s pretty much like Majima from the main games: insane, volatile, quite fond of Kiryu, and generally rather cool. After a near-fight over refusing to drink sake, they become friends and volunteer for a critical role in the secret mission. This turns out to be assassination of Yuuki Hideyasu.

Coffman: “Musashi and Majima are enlisted by Nagayoshi to assassinate him in a secret plot designed by Tenkai, a monk and chief advisor to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Because Hideyasu is Ieyasu’s son and heir, even though he apparently was at odds with Ieyasu, he could not kill him directly. So Tenkai sent troops to kill Hideyasu, and then kill those troops. This was a common strategy: you could assassinate someone, and then make it look like you were defending them by bringing their murderers to justice.”

With things going awry, Musashi and Majima avoid being executed and escape to an old temple. They’re pursued, and we’re introduced to Sasaki Kojirou, who fights Musashi and goes on to become his main rival in-game. As Musashi and Majima again escape, Majima asks Musashi to deliver his sword to his younger sister, before cutting a suspension bridge to plunge both himself and the pursuing soldiers to their deaths. Musashi eventually finds the sister, Ukiyo, who turns out isn’t Majima’s sister, rather Majima killed her father in a duel. She refuses to accept the sword and Musashi decides to give up the way of the sword and instead help her farm rice. Eventually bounty hunters visit her home searching for Majima and, given that Musashi also has a bounty on his head, a fight ensues and Ukiyo is accidentally killed. Now Musashi is wanted for her murder despite trying to save her. Hearing her dying words he decides to return to the way of the sword.

On the run again and being chased by bounty hunters, he is eventually aided by an old monk, who gives him a change of clothes and takes him to the Gion in Kyoto, a “pleasure district” loosely equivalent to Kamurocho. Here Musashi meets Yoshino, the top girl in the district’s most popular brothel (the Tsuruya), who looks alarmingly like Ukiyo and it eventually transpires is her sister. Of course Musashi is immediately enamoured. He also adopts a new name, Kiryu Kazumanosuke, and then takes on work as a bodyguard/general man for hire. He befriends Itou Ittousai, bodyguard for the Tsuruya and who is an amalgamation of Detective Makoto Date and Kawara Shirou from the other entries.

After several years of living incognito, a little girl, Haruka, comes to visit Kiryu. She wants him to find the murderer of her family, whom she incorrectly believes to be Miyamoto Musashi! Unable to pay Kiryu, she sells herself to the Tsuruya brothel (all the brothels had smaller girls as servants, doing things like serving drinks etc). With his fee paid, the game is afoot to track down the real killer of Haruka’s family (since in reality HE is Musashi), meeting up with various series favorites, such as clandestine Honami Kouetsu (Kage the Florist, the big info broker from the early games), and getting embroiled with conspiracies which go to the heart of who will rule Japan. It’s all thrilling stuff and makes for a rousing adventure.

If you’re feeling confused by this point it should be noted that the first four lengthy chapters of Kenzan are mostly backstory with battles, setting up events. There are a lot of characters to keep track of, many with pseudonyms, and a tremendous amount of intrigue tying them all together. It’s safe to say that even if Yakuza 2 is regarded as the high watermark for story in the early series, Kenzan just about equals it in terms of scope, complexity, and rich characterisation – though with a less twisting ending. It’s difficult to judge the quality of the Japanese writing compared to the English releases, but certainly the detailed setting and sequence of events make for utterly gripping participation. There have been other samurai themed games, such as the Way of the Samurai series, but Kenzan is demonstrably leagues ahead of the competition.

Kenzan follows the same structure as the other games in the series. You have a base area to work from and a main series of storyline missions to follow, accompanied by roughly 140 side-missions which you stumble upon and can complete for rewards. There are numerous restaurants, coin lockers, women to woo at the various brothels, a fighting coliseum, criminals to hunt down, and all the other expected stuff – albeit all set in the Edo period. With the combat now focusing on sword-fighting, there’s also a blacksmith who can create and improve weapons, similar to the weapon dealers, but with a much greater range of depth to the system. There’s also the obligatory mini-games, now with a more feudal flavour. For example, you can practice archery atop horseback, or find and raise baby turtles, which can be used for racing in one of the gambling dens. The raising aspect alone constitutes a game in itself, though you can ignore this and just bet on other people’s turtles. Some mini-games, such as bowling (yes, Sega managed to recreate bowling in 1605), are only accessible through courting the courtesans, so along with the bonus missions the ladies grant, it’s worth visiting them for the extra fun and games.

One key difference is how the game is split between being inside the Gion pleasure district, where you control Kiryu in his silk leisure clothing but without access to swords, and the surrounding areas outside Gion, where he reverts to standard traveller’s clothes and can equip weapons. It’s similar to how Yakuza 2 was split between Kamuracho and an Osaka district, except in Kenzan, the Gion district is much smaller than Kamuracho, and the surroundings areas are absolutely massive, comprising several interconnected maps. The Gion and outside areas are also much better connected thematically, and it doesn’t feel like you’re jumping on a plane to reach a new area.

In many ways, Kenzan is ahead of the other entries before Yakuza 5. This is logical when compared to the first two titles, since it followed on from them and was developed on the next generation of hardware. What’s interesting is how it eclipses even the follow-up games on PS3. Fans of the series complained about how Kamuracho is reused with each installment and, in the case of the PS3 follow-ups, whole art assets were recycled from the previous generation with only slight improvements. With Kenzan, everything is bespoke, having been built from the scratch. This means not only is the entire adventure tremendously refreshing, but the character models, textures and animations are noticeably better than in Yakuza 3, which in some places resembled its PS2 forebears.

It can’t be overemphasised how gorgeous Kenzan looks. When you see the range of colours and level of detail in the procession of drunken Gion revellers, it’s an awe-inducing moment. Outside Gion there’s a whole other town to explore, along with dojos, temples, tea rooms, open fields, shady forests, caves, a lengthy river to walk alongside, plus a few story-restricted locations. It’s not totally open ended, but there’s more freedom than previously and it does a good job conveying a seamlessly connected, living, functioning world. Washing women work at the side of the river, while errant children bully each other outside of resting areas. If you’re too tired to trek from one end of the prefecture to the other, then hop in a palanquin and get taxied.

The most significant difference between Kenzan and all the other Yakuza entries of the time, though, is the combat. Whereas before it was all about bare-knuckle fighting and using any nearby weapons, now it’s about one of three diverse sword styles, in addition to unarmed combat. Inside the Gion proper, swords are forbidden, so you’ll need to equip an umbrella or similar, or go at it unarmed. While the unarmed style may seem useless compared against swords, it has the advantage of being able to throw enemies and grab any nearby item, whereas with swords, your interaction is limited. Outside Gion swords are a must, and real-time weapon change can be initiated at the tap of the d-pad.

Greatswords are slow but powerful, made for fighting armored foes or those with projectile weapons, which it can block like a shield. Single swords have a diverse range of attacks, and plenty of swords to choose from. You’ll be using mostly combos of weak attacks followed by a strong finisher. Duel swords are a long and short blades and you can duel wield, which not only looks super badass, but it allows you to block attacks from ANY angle. The downside is that the combos available tend to have less pronounced finishers than the single sword style, though both styles have their uses. Each of the three styles also have their own unique heat actions for given situations. Kenzan also introduces Revelations to the series, with Kiryu carrying around paper and an ink brush, to sketch something interesting that increases his moveset. Although there’s a multiple choice question for each, it’s not too difficult to stumble through with trial and error. There’s a lot of depth to the swordplay, and it’s a little disappointing that subsequent games stuck to the standard brawler mechanics until the genre switch-up in Yakuza: Like A Dragon (though Yakuza 4 would shake things up with the introduction of multiple characters).

Kenzan still suffers from a core series issue, namely being a nightmare for completionists. There are several permanently missable side-quests and cut-scenes (including the best in the game, where Kiryu gains access to a flying contraption), made even more troublesome by the language barrier. Some side-missions also have rather bizarre requirements, which would be tricky to accomplish even in English. A guide is essential if you want to see and do everything. The other problem is that while it looks absolutely stunning, it still sounds rather empty. There is background noise in places, but outside of cut-scenes there’s no dialogue, everything is conveyed in text boxes, and the sense of immersion is lessened. It would have been infinitely cooler if while walking through the market you could hear merchants haggling with customers – instead you get little text boxes popping up, to convey what they’re shouting out. But as with most of the niggles you can raise against the series, these are petty and insignificant against the broader scope of how much it achieves.

Tragically, Kenzan never saw a western release, and most likely never will with major staff leaving RGG Studio that supported a Kiwami style remake, not to mention studio members stating that they’d have to do a full remake instead of a simple remaster/remix like Ishin got (Kenzan still has a lot of archaic PS2 era elements left over the studio seems uninterested in using in modern day). Also, the opening (yes, it uses a rap song!) and overall story which deals with young girls being sold would have been disastrous for Sega’s PR. The series had never done especially well in the west until Yakuza 0, and it’s likely that were Kenzan localised it would have sold the least, especially competing against the all-consuming domination of military sims in the seventh gen’s market.

Luckily it’s very easy to play on import, as the PlayStation 3 has no region lock. Also, apart from a few specific missions, almost every main storyline goal is pointed out on the mini-radar. Theoretically you could ignore all text, mess around and still finish it by following the arrows. The slightly more insane option is to print out Coffman’s guide, and play through it one page at a time. Not the most convenient option, but it makes for a rich experience. Additionally, once you complete the game there is a wealth of post-game content, involving a series of fun action challenges, such as running through obstacle courses in your underwear while carrying explosives.

Interestingly, had Sega decided to localize Kenzan, the game already contains a built-in glossary system that would have made it easy. Since it’s set in the past, some archaic words might not be known even to the Japanese, so whenever an unusual word is mentioned, it’s highlighted. You then have the option to push triangle and receive a little pop-up box explaining it. Useless to a non-Japanese speaker, but were it localized this could have been adapted to explain all manner of things and make the game more accessible.

As it stands, if you’re a fan of the Yakuza series, or Japanese games in general, you should consider putting a little work into playing through Kenzan. It ‘s totally worth it.

Musashi

by Eiji Yoshikawa

Hardcover: 984 pages

Publisher: Kodansha International Ltd

Language English

ISBN-10: 4770019572

ISBN-13: 978-4770019578

It would be remiss to discuss Kenzan without briefly examining the book Musashi on its own terms, since when the Japanese think of Musashi as a character, it’s often based on the romanticized image painted in Yoshikawa’s book. At close to 1000 pages, it will last as long as one of the Yakuza games themselves. You don’t need to read the book to enjoy Kenzan, but playing might help you to appreciate and provide the motivation to slog through the novel – though the story in each is quite different.

Musashi starts off portrayed as a troublemaking teenager, joining the army with his friend to participate in the battle of Sekigahara. His side loses and, through sheer luck, he and his friend survive. With surviving soldiers being hunted down, the two force their way through roadblocks and end up wanted men. Sheltered by an attractive woman, Musashi refuses her sexual advances and so she elopes with his friend. Alone, Musashi sets off to rescue his sister who is being held captive, but is captured himself and sentenced to death. As a prisoner he meets a young woman who falls in love and helps him escape. He is again captured and, instead of being put to death, is sentenced to three years of solitary study. Emerging from captivity, he promptly rejects the woman who saved his life and waited for his release, to instead pursue the way of the sword. What follows is a seemingly endless series of near misses as she chases after him while he rigidly sticks to his samurai code.

It could be argued that Kenzan the game is actually more palatable to a Western audience, since the portrayal of Musashi is one of a hedonist. He fights hard and plays hard too; gambling, drinking, getting into brawls and romancing women. In the novelization, he is portrayed as too puritanical for modern youth to relate to, some of his behavior is downright baffling, and his emphatic dedication to the way of the sword, at the cost of everything else, becomes extremely tiresome by the halfway mark.

Toshihiro Nagoshi and his team at Sega did a fantastic job updating the character of Musashi for a modern audience with Kenzan. Your appreciation of the original will be dependent on a predilection for outdated styles of thought.