Some games have the ability to transcend the bounds of entertainment and become virtual experiences, ones that lodge themselves in our brain next to the formative events of our lives. We’ve suffered the loss of our wives as James Sunderland in Silent Hill 2. We’ve saved the world, or a variation thereof, countless times, all from the comfort of our living rooms. The best of these experiences required little effort, to forgive some gaming conventions or control issues, to really get immersed and make their world our home for a while.

Not so for Sentient. This game nearly breaks its back under the heavy load of ambition, put upon its shoulders by the development team. The result is an enticing, yet unforgiving game, whose striking innovation plays a huge part in its downfall. It’s a story-driven adventure, where there is no time to let yourself get swept away by the narrative. A free roaming non-linear sandbox that prohibits exploration. A complex space station simulation, made unmanageable by restricting you to a single corporeal form. A futuristic, high-tech gem, trapped in the body of an old-fashioned text adventure.

Sentient is a much overlooked ambitious adventure simulation that first came to PlayStation owners in 1997. It was the result of two years of hard labor by the folks at Psygnosis’ external Chester Studio, thrown unto an unsuspecting populace with little to no warning whatsoever. Gamers of old remember the name Psygnosis, of course, but more as a developer of quirky and stylish, yet awkward, platformers like Shadow of the Beast in the Amiga era (all very much in the same style as their famous Roger Dean designed logo), or as the original publishers of DMA’s Lemmings. Formed in 1984, the Liverpool based company was acquired by Sony during the 1995 PlayStation boom, and they continued along as they always did. But they never seemed to get the attention they deserved (apart from mildly successful titles like Wipeout and G-Police).

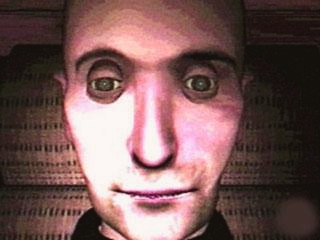

The few previews and reviews Sentient received heralded its astonishing AI and gripping plotlines, but it flew under the radar nonetheless. The PC version, with the aid of Visual Sciences, suffered a similar fate due to very limited graphic card support, leaving most players with low resolution VGA graphics – a badly rendered, washed out, glimpse of what it could’ve been.

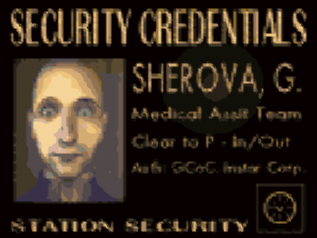

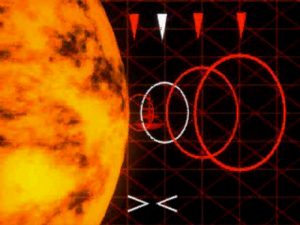

[/one_half]You are Garrit Sherova, a Medic sent to the Icarus Station to help treat and diagnose the recent outburst of Radiation Sickness. However this is not the only problem befalling the station – its orbit seems to be steadily declining, and is heading into the Xexor Sun. The ship’s captain has just been murdered. And tensions between the various crew members (much like the temperature onboard) are heating up. Not only that, the Senator visiting the station has become the target of an intergalactic political assassin known as Shatterjack, who is believed to be on board. And to make matters even worse, a level 5 solar flare erupts destroying the docking bay just as you are landing on the station.

The Medics:

The Engineers:

The Security:

The Scientists:

Thus begins an adventure that can lead you from being suspected to be Shatterjack, to being heralded as the messiah sent to save the station. From this point out it’s up to you, requiring that you make many tough decisions. For example, do you use the lightweight suit you just found on yourself, or do you give it to the gasping engineer laying on the floor?

For completionists, this game is a real nightmare. The compulsion for many adventure and RPG players (those being the most OCD-ish of genres) to find and see everything the game has to offer, will prove deadly in this game. There are 12 different endings to see, some with extremely varying events. Due to these intertwining plots, with their key events often happening simultaneously, under the constant time constraints, there is absolutely no way to experience the whole of Sentient in one sitting. You probably can’t even do it in ten sittings. Often times the AI of the characters will wander between several key locations, making running into them or their plot events differ on every playthrough. To add to the frustration, there are many unused items and half-finished plotlines to be found, often functioning as red herrings. As frustrating as this is, it really fleshes Sentient‘s world out even further, making it seem grander in scope and way more complex than it actually is.

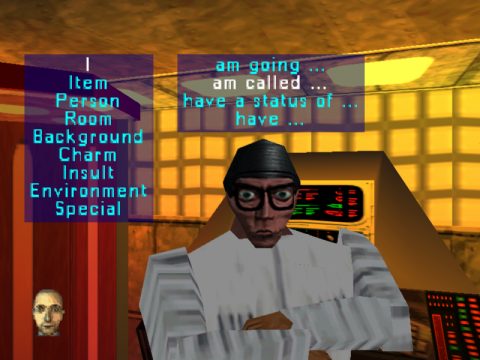

Sentient‘s interaction system is very reminiscent of the old text-parser adventures, or more specifically, the “use __ on __” type sentence building style. Except it’s extremely convoluted. And with a keyword system thrown in the mix. It even uses the old score system from the classic Sierra adventure games, though it’s hidden from the player. This gives a wonderful sense of possibility for interacting, not only with your fellow crew members, but also with the huge amount of machines, panels and objects in the station’s many rooms. Once you’ve identified a machine, by checking it, or introduced yourself to a character, it/they get added to your list. This extends as far as instructing one character to get an item or bring a message to another character. Which looks like this: Tell [character in room/character from list] that the [this room/room from list] has the status of [clear/locked/irradiated/on fire/destroyed]. It seems very overdone at first, but does really let you fully interact with the world.

You can adjust many aspects of the station, including the light, oxygen, and engine settings, truly making it feel like you’re actually on a space station. But much like the score system, the consequences are totally hidden and for the player to find out through trial and error.

Hampering the exploration severely however, is the time limit. This is where the real hurdle comes in. In the options screen you can increase or decrease three things: Disease Spread, Respect for Player, and Ship Simulator. Both the first and last settings directly influence your unseen time limit. And due to different event outcomes and AI choices, the time you have before the station reaches the sun, or succumbs to radiation disease, is influenced even further. Because there is almost no way of knowing how long you have to complete one of the storylines, the “You crashed into the sun” Game Over screen could stare you in the face at any moment. Roughly you can assume you have about 45 minutes to complete the first part of your quest (stabilizing the declining orbit), with certain story events tacking on extra time. It prevents you from sightseeing and really digging into the world, but it does bring a feeling of urgency and adds a lot of atmosphere. At least you can save any time you wish.

A lot of the perceived freedom, however, turns out to be mere padding. An early example of this occurs during a conversation. You overhear a tasty bit of gossip, that officer Voosto is having an affair with MedTek Lollie Downle, but asking either their opinion of each other yields only one of the (many) generic blurbs. This goes for items, event strands and environment interactions as well, to a degree. But there’s such a wealth of content that it becomes Sentient‘s greatest strength, in creating a believable game world, with a myriad of possibilities. And even though most of them turn out to go nowhere, there are enough different ones that do.

Sentience is a metaphysical quality of all things that require love, respect and care. The ability to feel, perceive and be conscious. The ability to suffer.

Another good example of this is the ship simulation aspect. Nearly every room has its own terminal that regulates the different functions of the ship – from oxygen supply and light levels on the Bio-deck, to propulsion and orbital control in the engine rooms. Not only is there a need for them during certain moments in the different storylines, you can also tamper with them to try and elongate your available time. Lowering the ship’s use of power on lights and environmental maintenance, and using that surplus to improve engine thrust, for example, will speed up the ship, thus making it drift faster towards the sun, and thus hastening your end. But if you’ve corrected the orbit in the “Into the Sun” storyline, the same action will stablize the ship’s trajectory, increasing your time limit. However, again, many of these functions and possibilities feel only half-implemented and it’s almost impossible to fully grasp their effect and purpose, if any exist at all.

Furthermore, there are countless machines in every room, and it’s hard to figure out what they all do. In room 214 of the 3rd Medical deck, you may find a smoking data interpretation unit. If left unfixed, it changes the outcome of some radiated crew member’s medical scan, thus releasing him from quarantine and making the rate of disease spread double. Some characters wander around fixing things, but again their routes and actions seem to alternate per playthrough. You can spend entire playthroughs following singular individuals, ordering them to fix or obtain things, and finding many different possibilities to influence ship or disease spread behavior, amongst other things. When you finally meet the ship’s own AI, S.U.S.I.E., again the possibilities seem endless.

And with the sixty two individually operating characters running around the station, with whom you can all build friendships with, you feel like you can truly shape Garret’s fate aboard the station. What seems like a point-and click adventure on the outside is actually more of a social simulation, combined with an outer space survival game. And so the first true (and only) social space station survival simulation adventure was born.

From a stroytelling standpoint, it is an unwieldy, clunky, convoluted game, with meme-worthy dialogue such as “I am poorly.” and “You smell like a deep-space pilot.” However, its unique qualities also add to the setting and style of Sentient‘s universe. Its use is consistent, and considering the nationality of the developers – it was natively written in English, ruling out bad translation – it seems quite deliberate. Think of the distinctly different ways of talking the Harkonnen and Fremen have in Dune, with their own quirky sayings and flow. Further evidenced by the obvious simularities between the Navigators in both IP’s and the Lynchian dream sequences.

What also helps is the expansive backstory, from the manual, but even more so from the extremely long and eventful FMV intro to the game.

Welcome to the New Hegemony. This is our future. Mankind is struggling to expand to stars unknown, as not only the Earth’s, but our entire system’s natural resources have all but dried up.

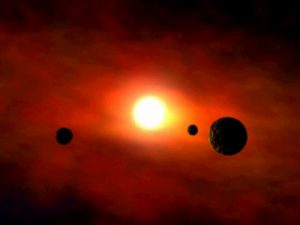

On the verges of stable space the universe continues to form, rolling out to fill the void like a liquid. A thin black frozen liquid carrying on its tides the promise of new worlds and the possibility for minds, which in aeons to come, may think as we think. And yet out here where nothing should yet exist, beyond the faint hopes of potential, we found Xexor.

The mystery of Xexor’s existence had been a short lived debate. Xexor is here, it is bright and it is healthy and (according to all stellar surveillance reports) it is teeming with the Kenyon fields which have become the Hegemony’s main power resource since the depletion of all other fuels. In a matter of mere decades, scientists had stopped asking each other why the star was here and had begun asking instead how best to mine this most valuable and sought after energy. These Kenyons however work two-fold, not only do they posses immense energy, they also seem to have the ability to store data in a way mimicking the human brain. Scientist’s have recently discovered these properties and have since been analyzing and speculating on its use as microprocessors. Some strains however seem to already contain strings of data, yet to be encoded.

After more than 20 playthroughs and pages of notes, every walkthrough and tons of FAQs you’ll still feel like you haven’t seen all this game has to offer. That makes Garrit Sherova a character to keep coming back to, even if it’s just to check if maybe by making some crew member repair that broken fuel-pump flow inhibitor in room 323, you’ll stumble into something new. By playing Sentient as the adventure simulator it tries to be, you’ll find it to be a game world worth living in.

Links:

Manual Download

Help File Download

Gamepage at Psygnosis The game’s main page at the Psygnosis site.

Developers Interview at The Gaming Liberty Retrospective Interview with three of the lead developers covering the bumps in Sentient’s production process.

Walkthrough at The Spoiler Complete walkthrough of the game including all alternate endings, subplots and scoring.

Walkthrough at The Computer Show Detailed walkthrough of the game including most alternate endings and subplots.

Hints, tips and FAQs at Gamefaqs Some helpful guides and information as well as walkthroughs.