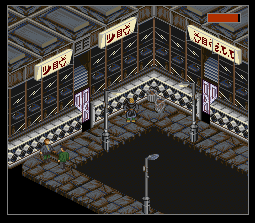

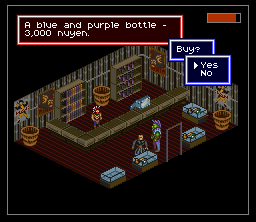

Pen-and-paper role-playing games are, now and probably forever, stereotyped as little more than fantasy-based Dungeons and Dragons clones. One of the major titles that defy this convention is FASA’s Shadowrun. The world of Shadowrun borrows heavily from cyberpunk lore, the genre practically invented by author William Gibson with his book Neuromancer, and the atmosphere is heavily influenced by Ridley Scott’s 1982 classic film Blade Runner. Expansive cities bathed in near perpetual dinginess, despite huge technological advances – Shadowrun‘s choice setting is a futuristic version of Seattle. Mega corporations rule over practically everything. And there’s an exaggerated sense of the ’80s-bred paranoia that the Japanese were going to take over the world, manifested in a heavy influence of Japanese culture, and the currency in this world is even called the “nu-yen.”

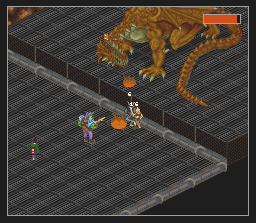

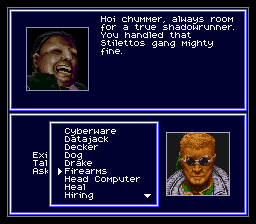

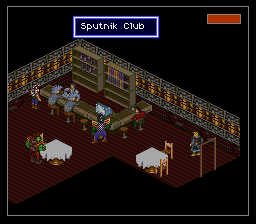

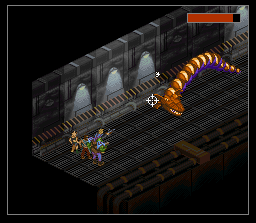

But Shadowrun does things a bit differently, by taking this dystopic landscape, filled with laser guns and computer hackers, and meshed it with the usual role playing conventions like magic spells and dragons. Humans share the world of Shadowrun with dwarves, elves, orcs and trolls. Players fight vampires and zombies with pistols and grenades. Amidst the techies that outfit themselves with the latest cybernetic enhancements to interface with digital landscapes, there are shamans who hold deep mystical beliefs and wield magic powers. The world is inhabited by strange people who speak English with their unique brand of slang (“Hoi chummer!” you’ll be greeted with many times, even as a complete stranger.) It’s a completely unique world which, naturally, made for some excellent video games.

During the 16-bit era, there were three Shadowrun games, published for the SNES, Genesis, and Mega CD platforms. Each of them were made by completely separate developers and offer entirely different takes on Shadowrun. None of them, however, strictly adhere to the guidelines usually applied to console RPGs. The SNES version blends elements of point-and-click adventure games with role playing elements. The Genesis version more closely mimics the rules and experiences of the pen-and-paper game, offering a hugely open ended game experience that’s closer to Grand Theft Auto than Final Fantasy. And the Mega CD game, released only in Japan, a digital novel with tactical combat segments liberally interspersed with the text. Even the 2007 release, published a decade after any of the 16-bit titles, takes the concept of a tournament first person shooter and seeks to reinvent it. The 2013 Shadowrun Returns is more along the lines of what one would expect, but puts an emphasis on its content creation tools. These reasons alone should be enough to convince anyone to adventure into the dark underworld of Shadowrun.

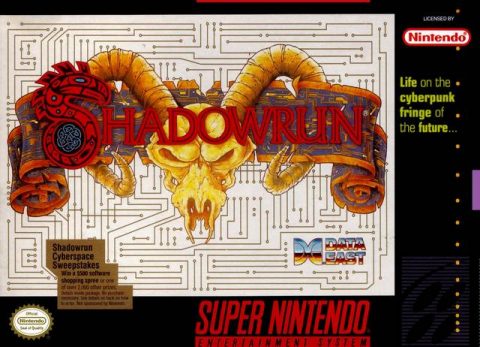

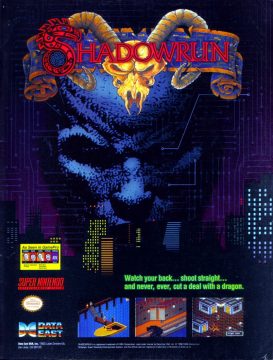

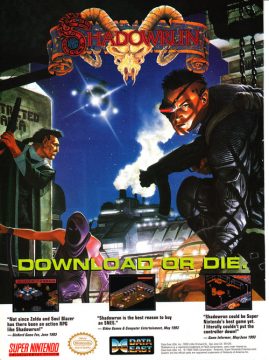

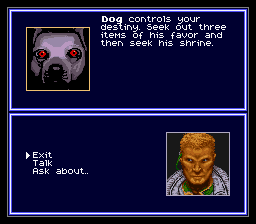

The Super Nintendo adaption of Shadowrun was developed by Australian development company Beam Software (also known as Melbourne House, which later became Krome Studios Melbourne) and published by Data East. As soon as the game begins, the protagonist Jake Armitage is seen getting ruthlessly murdered by a group of street thugs. Shortly after the thugs clear the scene, a fox crawls from the shadows, enchants his body, shapeshifts into a woman and runs away. The game starts when the morticians are putting Jake on ice. As soon as they leave the room, he awaken from his slumber, apparently unharmed despite being riddled with bullets just moments earlier. And as luck would have it, he has completely lost his memory. So after freaking out the morgue guys, he escapes, and finds himself facing a number of problems: Who is he? Who was the transforming fox lady? Why are there random snipers on the street shooting at him? Who is this man named Drake? And most bafflingly, why are talking dogs advising him of his destiny?

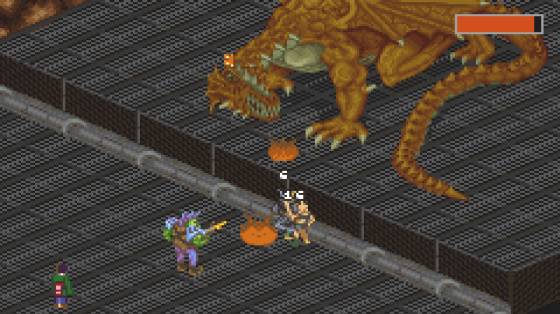

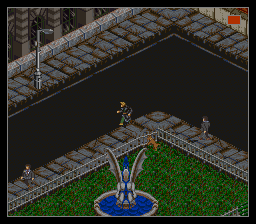

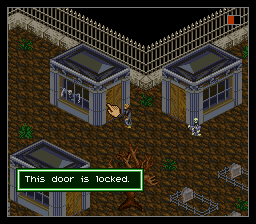

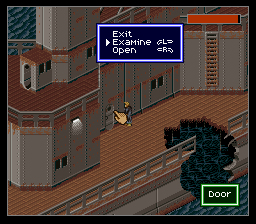

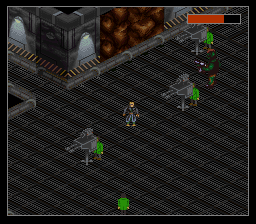

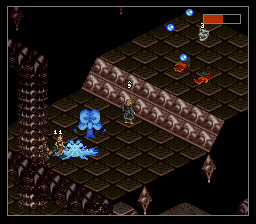

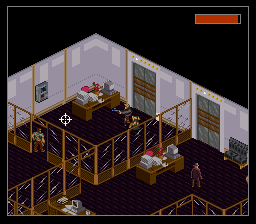

The game is an odd mixture of PC-style point-and-click adventure games with role playing mechanics. Although Jake is controlled directly with the directional pad, a cursor can be called up at any moment to look at the surroundings or interact with them. The interface is certainly very clumsy, especially when trying to attack enemies. All that’s to be done is pressing the attack button to activate the targeting cursor, highlight the bad guy, and keep hitting fire until someone gets killed. At the beginning, Jake’s skills are pretty weak, so he often finds himself missing targets even at point blank range.

This is where the RPG elements come in. Karma, Shadowrun‘s equivalent of experience points, is earned by defeating enemies. Whenever Jake goes to sleep, these Karma points can be used to raise various abilities and skills, ranging from extending the life meter to gaining computer hacking skills. Gaining Karma is tedious (especially at points where its required), but it can be lost as well. Shooting at friendly NPCs brings up a message to stop hurting the innocent. When ignoring the warning, one Karma point will be deducted from the current total.

There are also these cybernetic parts called Cyberware, which Jake can install on his body for boosts in certain aspects and stats, like the Wired Reflexes, which allows him to pull the trigger of his gun faster, and the Dermal Armor, which grants a bit of extra protection. Since Jake becomes entangled in shamanic tradition, he can also learn magical spells to aid himself in battle. Compared to other console RPGs, there’s a lot more freedom and interaction in developing the character, even though the plot itself is still pretty linear.

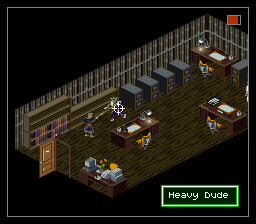

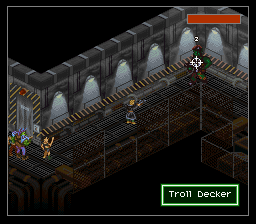

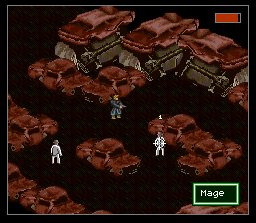

Although players technically only get to control Jake, several Shadowrunners can be hired as merchants, who’ll tag along and use their skills in any area where Jake may be lacking. They also aid in combat, where they are controlled entirely by AI. (In the early stages of design, there was to be tactical combat, with individual orders given to each companion, but this was unfortunately scrapped.)

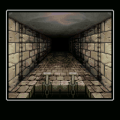

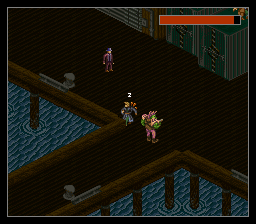

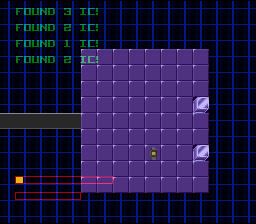

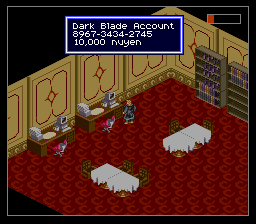

At a certain point in the game, it becomes possible to “jack” into the Matrix, a complex computer system (and world) that everybody wants to rule. In these short intermissions, the viewpoint changes from isometric to overhead, as Jake moves his avatar around this computerized world. The goal here is to try to retrieve data and be careful of various ‘mines’ that are in the way. These sections aren’t really that hard or interesting, since it’s really just trial and error, but they do their role in mixing the game up a bit.

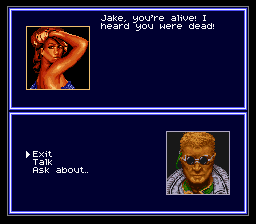

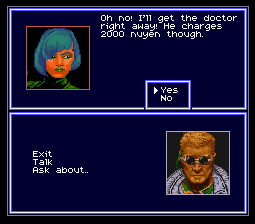

Many mysteries await their solving, so there is a lot of detective work to be done by talking to everyone around. Important people will mention highlighted keywords, which are topics of conversation that then other people can be interrogated about. Jake can ask many, many questions using the keywords acquired during various other conversations, but not everybody knows about all the keywords. During conversations, both Jake and his interview partner are represented by their mugshots. All the artwork is of mixed quality, but especially Jake’s face is so ugly that its a blessing some of it can be concealed by wearing sunglasses.

Shadowrun also has some really badass music. It’s a lot grittier than the average SNES soundtrack, but the sample quality is right up there next to the later Square games. One of the best themes is played in the morgue at the beginning of the game, driven by an electric guitar, a catchy bass line, and a haunting flute melody. While the number of tracks is low, they’re almost all excellent, and contribute heavily to the oppressive atmosphere.

It’s surprising to see such dark subject matter in a SNES game – Shadorun was released in 1993, before Nintendo loosened up its censorship standards, so seeing the protagonist brutally murdered within the first few minutes of the game is bound to have been quite a shock for many players. Yet there are points where Nintendo did some tinkering. Right at the beginning of the game, Jake needs to loosen the lips of an NPC. The only way to do this is by going to the bar, ordering his favorite drink – an “iced tea” – and delivering it to this character, who suddenly becomes a lot more talkative. There’s a beta ROM of Shadowrun floating around, which is slightly less censored than the actual release copy. In the uncensored version, the morgue is referred to as a “chop shop” (keeping in line with the pen-and-paper RPG), and rock musician Kitsune is a bit more flirtatious.

There are some minor problems with Shadowrun. Aside from the dull combat, it’s often a bit aimless, and it’s far too easy to miss small items, halting progress and requiring to scan over every visited scene. The interface could’ve used some work, but it’s about as good as it could be without the use of a mouse. Otherwise, Shadowrun has a fantastic plot, with superb writing – definitely superior to any of the Japanese translated RPGs on the system – and unique gameplay that has cemented its reputation as a cult classic.

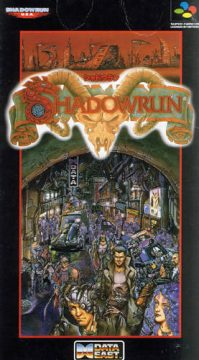

Data East also brought the game to Japan. This release is very odd – instead of replacing the text, all of the English is kept as is, with Japanese subtitles popping up around the screen. The interface has been changed a bit, too. In the English versions, when interacting with an object the default selection from the verb menu is “Quit.” This means the player has to point at something and manually select an action, even if there’s only one choice. The Japanese version instead highlights a default action, allowing to simply highlight an item and hit the button twice. On the downside, the L and R button shortcut mappings, which were meant to circumvent this issue in the English release, have been removed.