While nostalgia for the 1990s has become a cliche over the years, for anime, it feels at least somewhat appropriate. During this decade, artists and writers were given free range to experiment with whatever ideas they wanted, no matter how esoteric. Revolutionary Girl Utena is a perfect reflection of that: it’s hard to pin down what genre the show is, as it doesn’t borrow too heavily from any established genres. What it does offer are complex messages about gender roles, romance, and sexuality; an endless supply of symbols and literary allusions; and a theatrical flair to tie it all together. Some of this can make the show difficult to understand, but it’s also what lends the show its appeal.

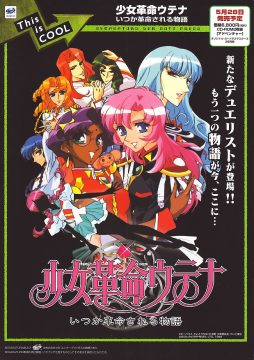

At the very least, it made the show attractive to audiences at the time. It enjoyed a relatively successful run, leading to a feature length film, a stage production, and even a video game for the Saturn: “Revolutionary Girl Utena: Story of the Someday Revolution”. Unlike other licensed video game tie-ins, though, the Utena game isn’t just a dating sim with the Utena name slapped on at the end. In fact, not only does the game understand the show’s values, it also knows how it should apply those values to dating sim conventions. The game may hit its limits in a few places, but it’s clear that the game is making a conscious effort to remain true to its source material, which is more than can be said for other games at the time.

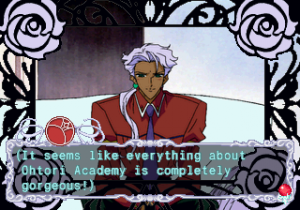

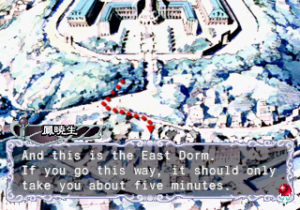

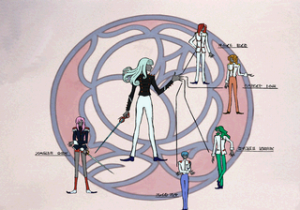

For those unfamiliar with the show, Utena follows the eponymous hero’s daily life at a prestigious school known as Ohtori Academy. She spends a lot of her time fighting the Student Council in a series of elaborate duels for control of the Rose Bride. The major characters include:

The Protagonist

A transfer student to Ohotori Academy, the protagonist serves as little more than the player surrogate. While she has some backstory, she mainly exists to react with wonder and excitement to all the schools events – just like the player would in this situation. She doesn’t even have an official name; the voice actors skip reading her name in the script, and the credits only list her as “protagonist.”

Utena Tenjou

The main character in the show (but not in the game), Utena Tenjou is boyish with an anti-authoritarian flair. She’s the only girl on campus who wears a boy’s uniform, and she challenges a lot of Ohotori Academy’s preconceived notions the minute she steps on campus. In the show, she spends most of her time either enjoying her school life, bonding with Anthy, or dueling the Student Council. The only difference here is that she bonds with the protagonist, as well.

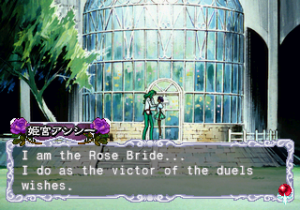

Anthy Himemiya

Utena’s friend and the second major character in the show, Anthy holds the title of Rose Bride. In theory, this means she holds The Power to Revolutionize the World. In practice, however, it means she’s essentially a slave to whoever last won her hand in a duel. Not that she has a problem with that. She’s glad to accept this, and is passive almost to a fault. She also has a pet monkey/mouse creature calls Chu-Chu.

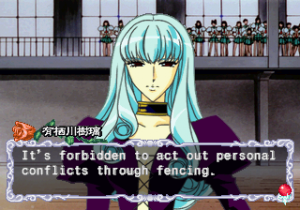

Juri Arisugawa

Juri holds the honor of being the Student Council’s only female member (within the game, at least). Personality-wise, she’s the opposite of Saionji: there’s an air of nobility about her, but she lacks the kind of posturing that some of the other characters have. She’s also a notable member of the fencing club.

Miki Kaoru

Unlike the other Student Council members, Miki isn’t as interested in the Duels or the power struggles that come with them. He’ll go along with their plans, but doesn’t show quite as much ambition as his peers. So it shouldn’t be surprising to learn he’s one of the few people that treats Anthy like an actual person.

(There are a few other recurring characters in the game, like Wakaba and Nanami, but they’re not as relevant to the game as Utena, Chigusa, or the Student Council.)

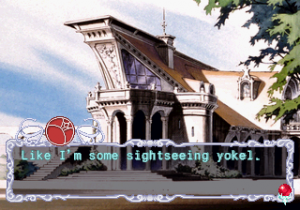

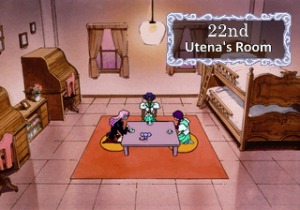

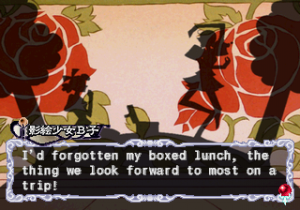

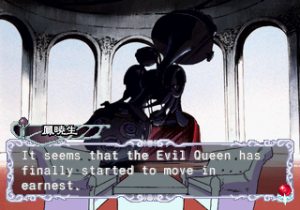

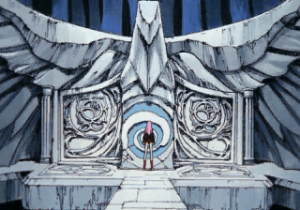

As some of these screenshots indicate, “Story of the Someday Revolution” doesn’t envision itself as a game as much it does an interactive episode of the show. The game goes to great lengths to recreate the look and feel of the show, repeating a lot of the visual motifs, cinematography and pacing to the best of its abilities. It even includes several animated sequences made especially for this story, like a few duels and a campy opening. Gameplay-wise, the game borrows a lot of its structure from Sakura Taisen, another Sega dating sim that presents itself like a TV show. (Given Sega’s involvement with both of these games, that shouldn’t be too surprising.) To its credit, the game’s efforts pay off. It knows what techniques to borrow from the show, and the end result feels like something that could have aired alongside any episode of the show. This would have appeased the show’s fans, who, at the very least, would have wanted to be part of the Utena story.

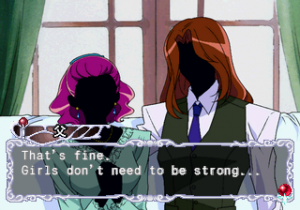

Yet to praise the game for simply resembling its source material would be to stop short of appreciating what it does on its own, as a game. This would also mean ignoring the game’s more noteworthy accomplishments. The show’s writers must have found it strange that they were adapting something like Utena into a dating sim. Why? Because the genre embodies the very ideals the show works so hard to fight against. Their protagonists are often nothing more than princesses waiting for their prince to make himself known. They don’t take an active role in getting what they want; they just wait for the opportunity to present itself and then react to the situation as it occurs. To a certain extent, this is because these are the only actions that dating sims can allow. The player has little if any control over the conversations in these games, so all they (and, therefore, the protagonist they control) can do is react to whatever the developers decided they’re allowed to react to.

In any case, “Story of the Someday Revolution” is aware of these implications, which is why it works so hard to debunk dating sim conventions. This is especially apparent within the story. Between the occasional allusion to Snow White, the story splits its focus between Utena preparing for a mysterious duel and Chigusa tormenting the protagonist whenever she finds an opportunity. The conflict between these two characters eventually culminates with one very important question the game poses: “Why isn’t my love worth as much as yours?” That’s what makes the game’s criticisms so poignant and incisive: they cut right to the heart of the genre. According to the game, anybody willing to treat high school as their own personal harem would have to be incredibly selfish, since they’re telling everybody else that their emotions just aren’t worth as much. Not only does that include an outside party like Chigusa, but, as the game demonstrates, it also includes the object of your affection! After all, your partner’s feelings on the matter don’t hold that much importance. This relationship is all about your own romantic desires. The game tears dating sims out from their root, showing how destructive and harmful they can be if left unchecked.

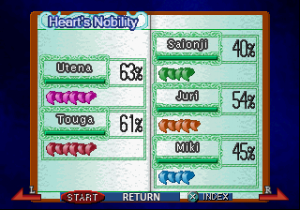

Naturally, the game also applies these lessons to its gameplay. In fact, it’s within the gameplay that the game finds some sort of solution to the problems it raises. You’re not expected to look at the students of Ohtori Academy as a means to fulfill your own romantic desires, but to treat them like equal classmates. In practice, that looks something like this: hang out with everybody a little bit, but don’t act so possessive toward them. Give them some space to breathe. Maybe even see Chigusa once in a while to keep her off your back. Whatever your strategy, the game’s core message is, “Put aside your own feelings, and don’t pursue any one person at the expense of everyone else.” This is a substantial twist on generic conventions, adding an air of selflessness and responsibility to the dating sim in a way that feels appropriate to what the show was about. Granted, “Story of the Someday Revolution” still looks a lot like the games it criticizes. You socialize with the cast, manage a multitude of relationships, choose what to say when the game asks you to, etc. Chigusa even acts like the bomb from Tokimeki Memorial, albeit more frequently and aggressively. Yet within the narrative context the game provides, these familiar mechanics take on an entirely new meaning. You’re not as concerned with fulfilling your own romantic desires as you are protecting everyone around you from Chigusa’s schemes.

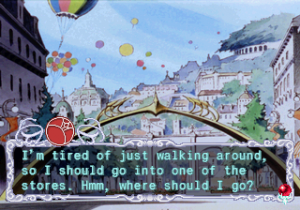

Which isn’t to say that the game has no place for the player’s desires. Indeed, one of the more notable aspects of the game is how it incorporates those desires into the Utena world. This is where its Sakura Taisen influences become the most important, as they’re what give the game its slice of life character. Romantic endeavors end up taking a backseat to experiencing what the world has to offer. All the world is there for you to wander, and it’s entirely up to you whether you participate in whatever event you find.

As counterintuitive as it may sound, what makes this approach tenable is how much it decenters the player. Although the story caters to the player a lot (sometimes to an implausible degree), framing the world this way still allows the other characters to exist on their own terms. They’re just another part of the world, not just an object for the player to mess around with. This doesn’t mean the player can’t get what they want out of the game. You’re part of the episode, after all, and given how much of the game takes place off campus, you stand to learn more about the Utena world than you would from simply watching the show. What’s more, the game’s non-canon nature (it takes place shortly after an episode that doesn’t affect the plot too significantly) gives the player free reign to experiment with the game as they please.

The only downside worth considering is how the game caters to its audience’s wishes, even as it castigates them. For a game that critiques traditional ideas of romance, “Story of the Someday Revolution” is surprisingly willing to let you see the cast naked. In fact, you can see almost every major character in a state of undress at one point or another. A strange thing to do, considering how much the game denounces the kind of objectification that fan service like this entails. It’s not even like these scenes serve any greater narrative purpose. They exist only to let the player see their favorite characters naked. The game is trying to have its cake, and eat it, too. And on that subject, the unlockable answering machine messages (along with Utena singing the show’s theme song) also arouse suspicion. They’re nice to have, but they also reach out to an otaku crowd that the show would have been critical of.

Be that as it may, “Story of the Someday Revolution” is by no means restricted to that particular audience. In fact, it’s worth contrasting this game against the Neon Genesis Evangelion game to illustrate that point, as they tackle similar challenges in completely different ways. Evangelion aims for a scene-by-scene recreation of the original story, but falls short because it doesn’t capture the spirit of the show. “Story of the Someday Revolution”, on the other hand, is more concerned with making sure its own story stays true to the Utena spirit. Not only does this feel more natural than a straight conversion, but it also opens up new doors that wouldn’t have been available to the game otherwise. It can take the game’s thoughts about gender roles and romance and transfer them to a new context where they might be needed. Sure, the game hits some rough patches, but at least it understands what it’s doing.

Links:

Fan translation at In The Rose Garden