“The fear of blood tends to create fear for the flesh.”

Capcom’s Resident Evil wasn’t the first horror adventure game, but it did codify what would become known as the “survival horror” subgenre. And given its massive international popularity, many other publishers rushed to create their own similar games. As expected, these all varied in quality, but the one series that not only stood up to Resident Evil, and arguably surpassed it in many ways, was Konami’s Silent Hill.

Resident Evil is a game about zombies, so its inspiration lies primarily with George A. Romero flicks like Dawn of the Dead. In contrast, Silent Hill‘s horror is more psychological, as fears and traumas find themselves manifested in the gruesome monsters that the main characters face. In facing these horrific creations, the heroes of the games stand up against their anxieties, giving the storylines far more thematic depth than the pulpy story of the evil Umbrella Corporation could ever hope to obtain. Each game has different protagonists, but the town of Silent Hill and its supernatural connections remains central to almost all of the games.

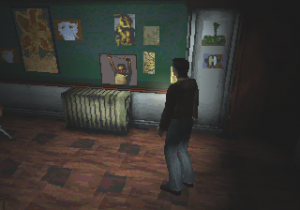

From a technical perspective, there are also significant differences, at least when comparing each series’ PlayStation entries. For starters, all of the graphics are 3D, as opposed to the 3D models over 2D backgrounds many similar games, and the camera is placed behind protagonist’s shoulders most of the time, changing to dramatic camera angles as necessary. However, the basic gameplay is the same, with a focus on ammo conservation and limited puzzle solving. It even features the same “tank style” controls as the competition, though given the rarely changing camera orientation, controlling the character is a little easier.

The Silent Hill games were developed by staff within Konami who eventually became known as Team Silent. The first game was directed by Keiichiro Toyama, who left the company shortly after to join SCE Japan Studio and create the Siren series of horror games. Both the visual style and writing are central to the feel of the series, which are credited to visual designers Masahiro Ito and Masashi Tsuboyama, and writer Hiroyuki Owaku. Musician Akira Yamaoka lends his distinct stylings to the soundtracks, and he later become involved more closely as a producer. The team was disbanded after the release of Silent Hill 4 on the PlayStation 2 – some remaining staff eventually left to join Kojima Productions, while the games themselves were outsourced to various Western developers.

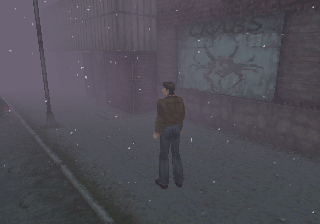

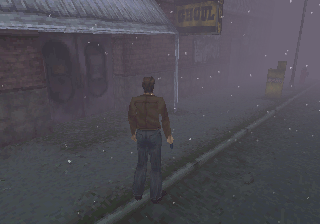

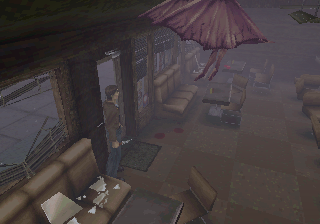

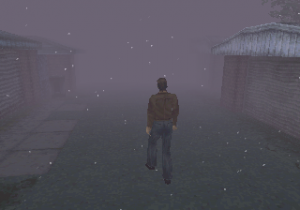

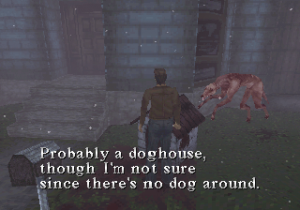

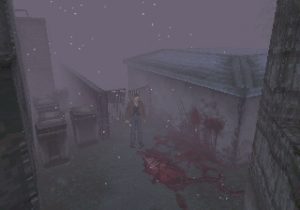

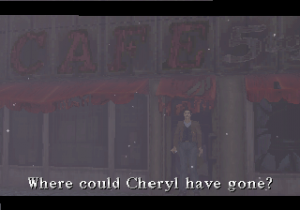

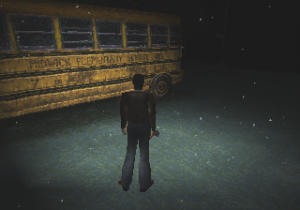

Released in 1999 for the PlayStation, the original Silent Hill tells the story of Harry Mason and his daughter Cheryl. They’ve recently set out on a trip to the eponymous town for a little vacation. Things go awry, though, when a young woman appears in the middle the road. Harry swerves to avoid her, causing his vehicle to crash through the guardrail and land on the pavement below. When he regains his senses, he finds that his daughter is missing from the passenger seat. He exits the vehicle to find himself on a street in Silent Hill. It appears to be snowing out of season, and a thick fog covers the town, making it difficult to see more than a few feet ahead in any direction. Harry resolves to search the town and find his daughter, with the rest of the game entailing his journey.

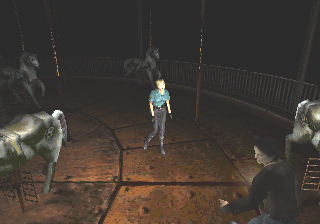

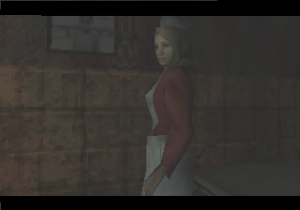

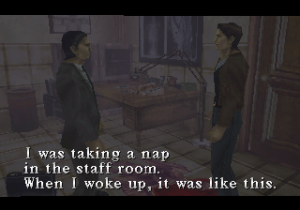

Though the town is largely deserted, there are other characters to be found, though each of their existence is enigmatic. Cybil Bennett is a police officer from a neighboring town who seems friendly enough, and even equips Harry with a gun. Michael Kaufman is a local doctor with some clear secrets to hide, and Dahlia Gillespie is a creepy old woman who rants and raves about the town being consumed by the demon Samael. And Lisa Garland is a nurse at the hospital, the most defenseless of the characters, who looks to Harry to guide her from this nightmare.

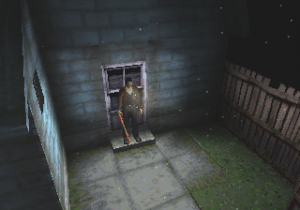

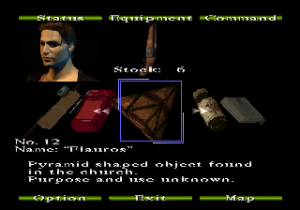

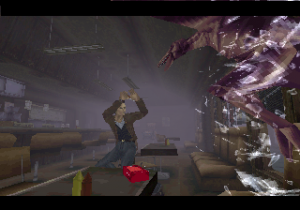

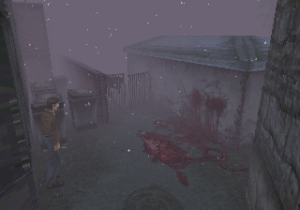

Compared to many other horror games, the player character of Silent Hill isn’t a cop or a soldier of any kind – he’s just a normal man, trapped in a situation that’s far outside his realm of experience. To that end, Harry isn’t that agile, nor is he an expert marksman. Indeed, you’ll find that even with the game’s auto-aim feature, some of your shots will miss their target. This is especially true if there are more than a few feet between the two of you. Even if you do connect enough hits on an enemy to make them fall, that isn’t the end of the encounter. After a few moments, they’ll get back up and resume the fight. To truly eliminate their threat, you must stand next to them and stomp on their bodies a few times. While this can definitely be seen as an act of self-preservation, there’s also a sense of brutality to these moments. It’s somewhat passive to take a life through firearms. Silent Hill forces you to really get dirty and break the bones of your opponents to ensure your own safety. By comparison, it seems almost mundane for a member of a special forces unit to decapitate some random zombie with a shotgun blast. Speaking of guns, as the game is set within a typical small town, the weapons in Silent Hill are a bit less exotic than some other action titles. You won’t find any acid grenades or infinite rocket launchers, but there’s still a rather fair variety of instruments to utilize on your opponents.

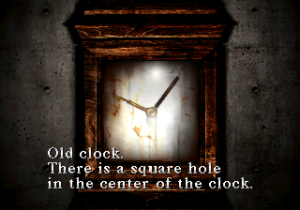

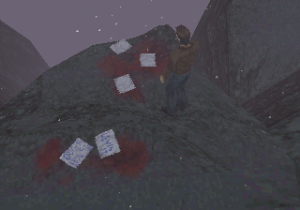

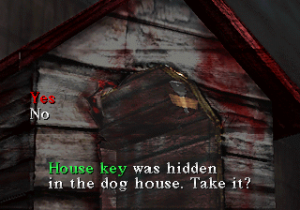

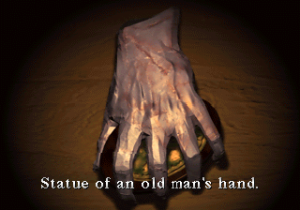

The town of Silent Hill is fairly large, and you’re allowed to explore a bit, though not much. Neighborhoods will randomly be cut off by chasms, conveniently railroading you to the next destination as the plot requires. Thankfully, Harry is quite handy with maps – he’ll helpfully mark off your current destination, scribble out locked doors, or make notes of areas of interest. These maps are not the typical, abstracted kind usually found in video games, but rather realistic looking road maps and floor plans, a unique detail.

The town of Silent Hill is fairly large, and you’re allowed to explore a bit, though not much. Neighborhoods will randomly be cut off by chasms, conveniently railroading you to the next destination as the plot requires. Thankfully, Harry is quite handy with maps – he’ll helpfully mark off your current destination, scribble out locked doors, or make notes of areas of interest. These maps are not the typical, abstracted kind usually found in video games, but rather realistic looking road maps and floor plans, a unique detail.

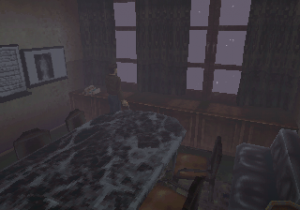

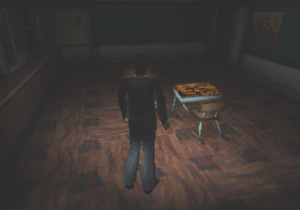

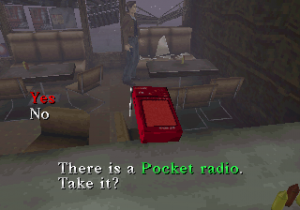

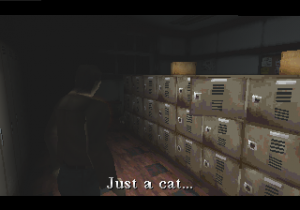

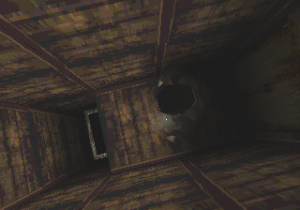

Outside of combat and your menu, Silent Hill places a large emphasis on sound and light. Relatively early on in your journey, you’ll find a flashlight and a radio. These two items are nearly as important as your gun when it comes to surviving your ordeal. This is due to the nature of the town in comparison to other games of this type. When Harry arrives, the place appears to be completely abandoned, with several roads covered by barricades or fallen debris. Others simply break off into seemingly bottomless pits. With that in mind, many of the places you explore will be pitch black and lacking electricity, making your flashlight the only method of getting your bearings.

As for the radio, where the flashlight can be considered an extension of your eyes, the radio serves as your ears. Whenever an enemy gets within range, the device will give off a stream of white noise, serving as an early warning system of sorts. The closer you are to a monster, the louder the noise becomes. Additionally, your enemies can see the light created by your flashlight, and are drawn to it. For this reason, it can be in your best interests to turn your light off at times, and use the noise of your radio to help evade your opponents.

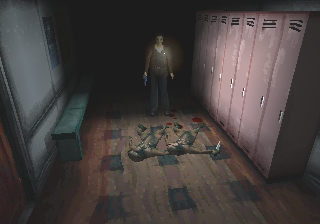

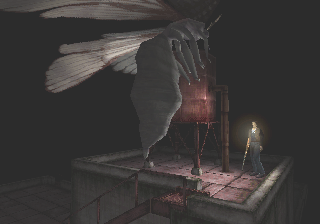

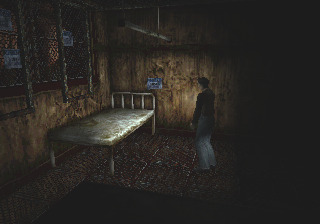

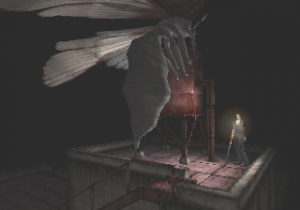

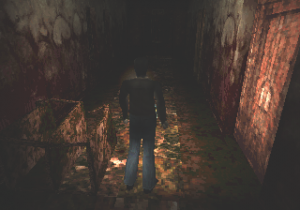

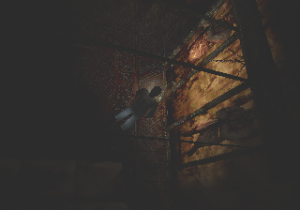

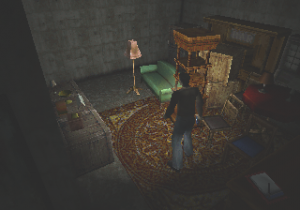

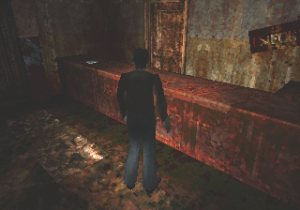

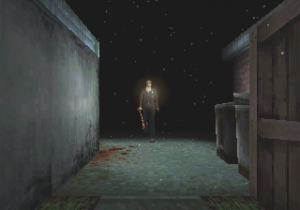

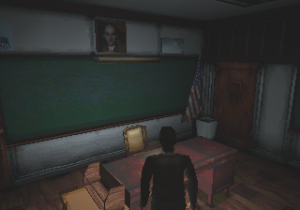

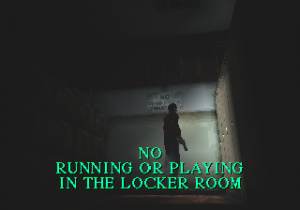

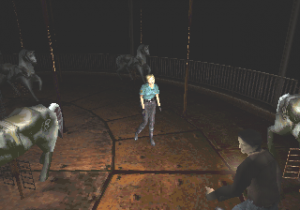

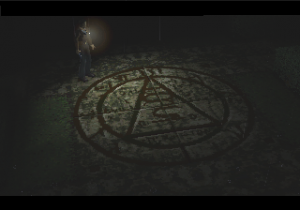

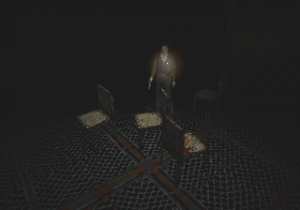

Along with the use of light and sound, Silent Hill also stands out from other survival horror games through the implementation of something known as the “Otherworld”. Harry’s quest to find his daughter will take him through many areas of the town, including storefronts, houses, an elementary school, a hospital, a shopping mall and an amusement park. Most show at least some level of disrepair, but this is nothing compared to this sickening alternate dimension. From time to time, a loud siren will be heard in the distance, marking the shift to something that could be described as an industrialized version of hell. Floors and walls are replaced with rusted metal grating, with dead bodies hanging from chains and covered in occult symbols. The rusted out walls and floors seem to serve as a mockery of the more normal versions, with blood smears and grime serving almost as the wallpaper. The darkness even seems to feel heavier in these parts, to the point of almost being suffocating. New paths open up within each area with the shift, while previously open ones are blocked off. This is compounded by the fact that the unnatural fog of the town is replaced with an ominous, all-encompassing darkness. It becomes almost a relief when you revert back to the “normal” world and the relatively manageable level of insanity it entails.

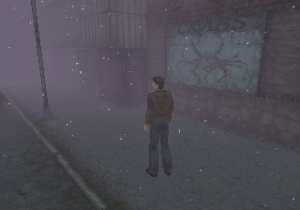

That fog, of course, can be thought of in a couple of ways. Developers often made use of it back in the mid-to-late 90s, where it served as a relatively cheap method of reducing a game’s draw distance, and it could certainly be said that the fog in this game serves a similar purpose. It also ties in with the Stephen King story The Mist, believed to be a major inspiration, which has a similar idea of a small town covered in a mysterious fog that cloaks the presence of horrific monsters.

The character models and environments do look rather rough. Harry runs in a very unusual fashion, arms and legs akimbo, as though he has some kind of problem with his joints. However, this extends over to your enemies, as well. Most of them come across as oddly-shaped brown and red blobs that vaguely resemble dogs or birds or people. But there’s a certain grittiness to be found in the low resolution textures, the short draw distance, and the choppy frame rate. They give it a stylized, abstract look that gets lost in later installments due to the improvements in technology.

Indeed, it’s the largely this off-kilter atmosphere that makes up the Silent Hill experience, and it consists of more than just graphical details. On a moment-by-moment basis, all you’re really is alternating wandering through towns and hallways, checking every door possible, scrambling to your next destination while occasionally killing a gruesome creature or solving a negligible puzzle. Rather, Silent Hill is all about experiencing a lucid nightmare. The “Otherworld” is representative of familiar areas in your psyche, twisted into a vile corruption. Most of the game is spent frantically running down hallways, grasping at the seemingly endless number of locked doors, hurtling through the darkness as nothing but overwhelming dread surrounds you. Logic ceases to enter into the equation – you may enter into a door and find yourself transported to a whole other floor.

There’s a certain dream-like quality to way that the characters act. Harry is distraught his surroundings but his singular focus on finding his daughter takes precedence. Neither Cybil nor Kaufman have any real handle on the danger they’re in; the only character that seems to have any vague grasp on the situation is Lisa, who is, understandably, scared out of her mind. The voice acting ranges between “serviceable” and “poor”, but the uneven tones of each awkwardly delivered line somehow works in its favor, in a certain kind of way.

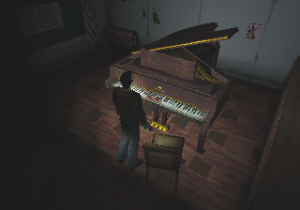

The outstanding quality of the music, at least, is less debatable. Much of the soundtrack has a very industrial feeling to it, with many tracks giving a sense of echoes reverberating through dark, damp and rusted corridors. The overall effect is rather imposing, and suits the atmosphere of the game. The overall sound design also makes good use of the “less is more” approach. Some of the most terrifying moments in the game can come from just the sound of your footsteps in a small, tight corridor, illuminated only by your tiny flashlight. You’re lost, running low on ammo, and then you hear the harsh sound of the radio telling you that you’re not alone. And when the gears and pistons begin pounding louder and louder, you can be sure you’re in for a fight against something particularly nasty.

There are a few other more traditional songs throughout. The intro track is led by an old instrument called a cimoblin, which lends a creepy, Eastern European feel, along with the type of bass guitar riffs made famous by Twin Peaks. The influence from Portishead is entirely clear. One of the ending songs, “Esperándote”, is a melancholy Spanish song that, while suitably depressing, doesn’t really fit along with the rest of the soundtrack.

For all of its harsh detachment, Silent Hill can get emotional when it needs to. At one point, one of the characters realizes that they’re turning into the same kind of faceless monsters that inhabit the rest of the town. They hurl themselves towards Harry, bleeding from all orifices, changing into something indescribably terrible, with only one desire – to be held. Harry, horrified beyond words, scrambles out of the room and barricades the door. When he returns, there is absolutely nothing left. Harry’s reaction is more than understandable, but tragic, and it’s an unintentional sin he can never truly atone for.

And yet, the game does occasionally get lost in its obfuscation. There are multiple endings (one of which pays homage to the ending of the movie Jacob’s Ladder), but no indication of where or how to undertake the subquests to get the good ones. It’s a short game, like many of its kind, but it’s annoying to find that you’ve irreversibly missed an important point without any clear signal. Still, it gives quite a bit of replay value, and there’s much goofiness to be found in the secret fifth “UFO” ending, which gives some absurd levity to the otherwise brutal proceedings.

There’s plenty of absolutely brilliant moments in Silent Hill, even if the most memorable ones can just as well be chalked up to bad writing or system limitations. Even from a less ambiguous perspective, it’s certainly much better than other similar games of the era, like Countdown Vampires or T.R.A.G. It’s one of those rare games where the flaws define it as much as its strengths, and still comes out as a fascinating product.