- Silver Case, The

- Silver Case, The: The 25th Ward

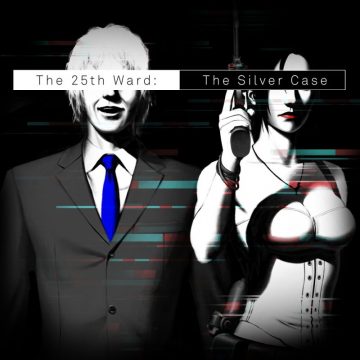

With the DS remaster of Flower, Sun, and Rain from 2008 and The Silver Case‘s 2016 remaster, the release of this full-on remake of The 25th Ward in 2018 marks the complete localization of Grasshopper Manufacture and SUDA 51’s Kill The Past thematic series, alongside Killer7, Killer is Dead, and the No More Heroes games (though Human Entertainment’s Moonlight Syndrome remains as elusive as always). Originally a Japanese mobile release that was only up for play from 2005 to 2011, the game has been a missing piece to the puzzle for western players for a long time now, fan translations not even possible due to the way it was distributed. It’s fitting that it ended up being the final one of these games to get a proper translation too, because The 25th Ward, especially with the new chapters added in this version, manages to tie up every theme and idea shared by these games with a nice little bow.

Granted, trying to following the stories contained logically remains near impossible. The game does a one up on The Silver Case by having three story lines, with Suda and Ooka returning for Correctness and Placebo, while also introducing Masahiro Yuki as the writer for Matchmaker. All three stories run in parallel – or at least do at first, before Correctness takes a massive jump forward around episode three. Correctness follows two HC detectives, the crass ballbuster Kuroyanagi and slightly dim rookie Shiroyabu, as they investigate a series of crimes connected to the Postal Federation’s delivery men and possible government ordered hits on civilians. Placebo has the returning turtle loving reporter Tokio Morishima brought into the ward with no memory and the vague mission to investigate a new Kamui themed website. Lastly, Matchmaker introduces Tsuki and Osato, another vet and newbie team of delivery man managing divers who work for the Federal Adjustment Bureau, quickly stumbling into a conspiracy relating to a thought long gone yakuza clan. Connecting all three stories is the threat of a returning Kamui, as we see people start to worship the serial killer and disrupt the order of the ward. However, it doesn’t take long for things in all three story lines to go in very different directions – ESPECIALLY in Correctness.

Yuki’s Matchmaker chapters are definitely the most out of place of the three, but not for a lack of trying. The writing in his story is far more straight forward, less interested in creating thick and meditative atmosphere and more in examining his own characters. While it’s the weakest story line, partly because it feels unfinished (a planned sixth chapter was never made originally and wasn’t added for this version), its straightforward nature makes it a great pallet cleanser to the more dense writing from Suda and Ooka. He’s also a much better comedic writer than either, using classic comedy pacing and personalities to put out a lot of darkly fun gags, the first two chapters having some of the funniest bits in the entire Grasshopper Manufacture library. While the style is different, it remains thematically resonant with the other chapters by focusing on that ever familiar theme of struggling with the past, plus some absurdist political commentary with how nice the state sanctioned murderers generally are in private.

His stuff is solid, but it pails in comparison to the Placebo chapters, Masahi Ooka showing his own experience as a writer by diving deep into Tokio’s psyche and creating some of the strongest moments in the whole game. While Matchmaker is most interested in dealing with troubled pasts and understanding one’s self, Placebo this go around focuses on the theme of purification. Tokio’s journey is a deeply personal one that starts to dive into his own psyche, using his awakened powers to toy around with what you’re experiencing as a player. His last few chapters start breaking the boundary between the reality in the story and Tokio’s reality, connecting you with the depressed medium on a very emotionally resonant level. For him, the journey isn’t about stopping an evil or understanding himself, it’s about coping with all the misery and sorrow he’s had to endure for so long. The additional final epilogue chapter, YUKI, is also easily the highlight of Tokio’s story, bringing back an unexpected setting for a very satisfying cap on this era of Grasshopper’s work.

Of course, Suda steals the show in Correctness, which flows in a similar manner to Transmitter from The Silver Case. At first. Kuroyanagi really stands out as a pile of contradictions that all break from the traditional Japanese woman archetype, a perverted closeted otaku who acts like a complete ass because she’s the best and knows it, making sure everyone else does too. Shiroyabu compliments her well, adopting her violent badass persona to make up for his inability to logically piece things together, usually treated as everyone’s whipping boy. He acts more as an outsider who needs things explained than even your own POV characters, including Kamui Uehara. No, not that one. In true Suda fashion, the game never really explains what the deal is with this Kamui, and it starts to become clear he might not even exist, the first major clue being that nobody on the HC unit is instantly alarmed when this new guy is transferred in while having the exact same name as a famous serial killer that nearly sparked a complete revolt not too long ago.

It’s the third chapter where things dive into Killer7 surrealist territory and the stories start to disconnect, simply because it would be impossible to try and connect the new plot Suda came up with any other narrative. The villain switches to a man named Kurumizawa, and your connection within the story through a POV character goes from shaky to shattered. Shiroyabu comes into his own as a disgustingly human person as the structure of the story begins to unravel, and it’s not just the divide between in-universe reality and character viewpoint reality that breaks apart, but the one between the player’s perspective and their understandings of the rules of fiction. By the end of the story, any sort of traditional narrative has been completely broken apart, the forth wall completely burned to ash, and it works incredibly well for Suda’s intentions.

What results is a brilliant political and social satire, showing how modern society’s dehumanizing nature and culture of conformity can bring out the worst in all of us, while also only being the initial layer above a deeper exploration of the entire concept of the protagonist and our own relationship with stories. After awhile, we’re not given a real reason to invest with the characters on any level, and the ones we do side with have minor importance in the main plot. The rules of the world no longer start to function as we’re exposed to characters existing in a way that doesn’t at all match the art style, characters seeing things nobody else can or logically should, and following random thoughts from nameless antagonists as the structure goes from second-person viewpoint to third and even first for random characters that get constantly shifted around.

That doesn’t even get into chapter four, which makes one of the most unexpected character shifts imaginable that completely shatters any possible continuity between this, The Silver Case and Flower, Sun, and Rain. It’s almost as if Suda wanted to shatter our sever our usual methods of connecting with stories, especially in the new last chapter made for this version. Without giving it away, it is the single most SUDA 51 thing he has ever written, and that is saying a lot. The connecting tissue between the politics and meta commentary could very well come from how POV characters are used, completely robbing the player a place in the story until the final chapter, where it shifts into absolute mockery. It can be argued a major attraction of games is the illusion of being able to assert ourselves into a story and have a real, meaningful place and impact on it, giving us concrete meaning reality ultimately lacks. Just as the 25th ward and our own world robs us of individual, egotistical meaning, so does the game itself, leaving you to either ponder, be wrapped in confusion, and reacted in livid frustration.

What makes these chapters so engrossing is that they’re so purposefully alienating from the scope of classic literary and game design norms. There is real meaning and depth in every scene, but the narrative cares so little about you or trying to please you. It either trusts you can follow along with what its saying (which isn’t too difficult, thanks to those random spots of inner thoughts), or it simply doesn’t care. It’s not unlike Spec Ops: The Line in that respect, but instead of being designed in a way to provoke and enrage the player, it simply ignores the rules to tell a story that doesn’t require the player in a medium used to working within the expected wants and whims of the player (the new final chapter primarily used to troll in a very open way). It’s a bold choice, but it works to the benefit of the game itself, especially with the wider themes at work. It all comes back to Kurumizawa, a bizarre anomaly that twists the entire concept of the story on its head and serves as a whole melting pot of symbolism and metaphor. How the Kamui effect from the first game weaves back into the narrative and what even Kurumizawa even is makes for the connecting piece of the puzzle that makes every narrative thread and theme come together to make a cohesive but complex whole. Like Suda’s best work, it leaves you thinking and mulling over what you just experienced, revealing new layers even years after if you’re willing to engage with it.

The game is mechanically the same as The Silver Case was in this version, with a significant amount more password puzzles that all prove to be incredibly simple. No joke, there’s a password in Matchmaker that’s just the name of the place you’re at. That’s not a bad thing, mind you, as difficult puzzles would only distract from the thick narrative. There are a few interesting bits early on, though, especially a maze and key puzzle in chapter two that has a remix version in Placebo with different solutions but a similar path. The purpose of these sections seem more to serve the themes of the story than anything else, or to purposefully disappoint and antagonize the player. The chat puzzles in Placebo are as funny as they are frustrating, the answers to many of the questions seemingly random, and the game well aware of it as it snickers under its hand. The highlight remains in Correctness, though, as you’re forced to go through an entire hotel worth of floors and rooms to find a single person. It’s not as bad as it sounds, but solving the puzzle is impossible unless you approach the task like you have to check every room.

What really makes the whole experience pop is the complete graphical overhaul. This modern version has been sold as a complete remake instead of The Silver Case‘s remastering tag, and you can definitely see that just from how well the old work fits with the new added chapters in Correctness and Placebo. Like The Silver Case update, the art and hud style changes among each chapter set, shifting from chapter to chapter at times, especially in Placebo’s last chapter. Said new art and hud assists are absolutely beautiful, with complex and abstract backgrounds moving as the picture frames pop in and out. It’s quite engrossing in the nigh hours, especially the Placebo chapters, when paired with the experimental soundtrack. It never sticks out at you outside the fantastic opening title track, just doing its work in the background and adding to the atmosphere.

Mobile Version

Mobile Version

It’s hard to compare this new version to the old due to its presence online basically being non-existent outside a scant few screenshots, but what comparisons that can be found definitely show that this is the definite version of The 25th Ward. The translation is great outside a few odd choices for trying to make untranslatable puns work, and the amount of improvements and added content is beyond impressive. Most importantly, if you truly want to understand SUDA 51’s early work, you absolutely must get around to playing this one. It caps off every idea from the early Kill The Past games, and you can even see some of the more meta blueprints from No More Heroes being worked out here. A visual novel that deserves to be known as one of the best in the genre, and definitely one of the most unconventional, even by the studio’s usual standards.