- Sonic Generations

- Sonic the Hedgehog

- Sonic the Hedgehog 2

- Sonic CD

- Sonic the Hedgehog 3

- Sonic & Knuckles

- Sonic the Hedgehog 4

- Sonic Mania

- SegaSonic The Hedgehog

- Sonic The Fighters

- Sonic 3D Blast

- Knuckles’ Chaotix

- SegaSonic Bros.

- Sonic the Hedgehog (8-bit)

- Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (8-bit)

- Sonic Chaos

- Sonic the Hedgehog Triple Trouble

- Tails’ Skypatrol

- Tails Adventures

- Sonic Labyrinth

- Sonic Drift

- Sonic Drift 2

- Sonic Blast

- Sonic R

- Murder of Sonic the Hedgehog, The

- Sonic Advance

- Sonic Advance 2

- Sonic Advance 3

- Sonic Rush

- Sonic Rush Adventure

Sega was one of the largest arcade game developers during the 80s, but they didn’t quite have the same success in the console space. The SG-1000 and Sega Master System was trounced in many territories by Nintendo’s Famicom/NES, particularly in Japan. And while it had gotten an early start in the 16-bit generation with the release of the Mega Drive in 1988, Nintendo was set to release the Super Famicom in late 1990, where it was expected they would crush the competition.

Sega’s plan to fight back was a mascot character, someone that would be as recognizable as Mario or Link. During the Master System days (and at the Mega Drive launch, the closest they had was Alex Kidd, a monkey boy who could break rocks with his fists. His games were relatively popular, but he obviously didn’t have as wide appeal as Nintendo’s characters, and his games, while enjoyed by Sega fans, just didn’t reach the same level of quality either.

Their solution was Sonic the Hedgehog, a blue spiked mammal with attitude, capable of zooming through levels with speed and exhilaration. It not only gave a recognizable face to Sega, but also created a technical showcase for the Genesis, giving a reason for gamers to upgrade their crusty old NES, or potentially lure them away from the SNES.

Sonic began development in a department called Sega AM8, where the company solicited designs for this new mascot. The selected character was created by Naoto Oshima, who had previously worked on the two Phantasy Star titles, as well as Last Battle. Several other team members were selected to join the newly formed Sonic Team, including Jina Ishiwatari and Rieko Kodama (also known for her work on the Phantasy Star games, as well as many Master System titles), as well as designer Hirokazu Yashura, who had only been with Sega for a few years at that point, having worked on the Genesis port of Altered Beast. The game was programmed by Yuji Naka, one of Sega’s most talented minds, who created some absolutely brilliant graphical effects for Master System games like Space Harrier, Black Belt, and (again) Phantasy Star.

The specifics of the world of Sonic the Hedgehog are somewhat distorted, particularly between the original Japanese version and the localized English version, especially given the assorted media later produced in North America, particularly the cartoon and comic book series. But the general setup is: there’s an evil mad scientist named Dr. Robotnik (or Eggman in Japan) who seeks to harness the power of the mysterious Chaos Emeralds. To this end, he kidnaps animals and turns them into evil robots, and it’s up to Sonic the Hedgehog to save the day. In the American version, the game takes place on the planet Mobius, while in the Japanese version, there’s no specific planet, as it just takes place on a location called South Island.

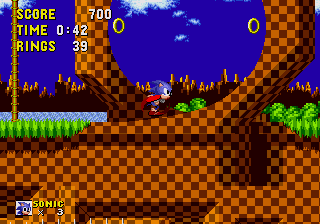

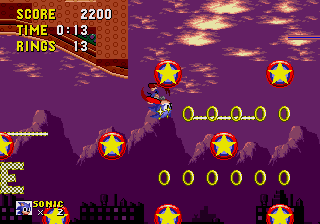

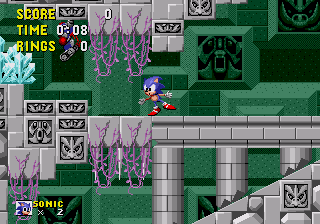

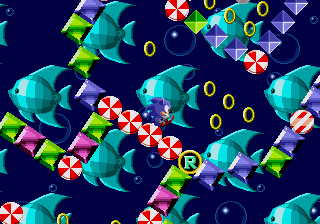

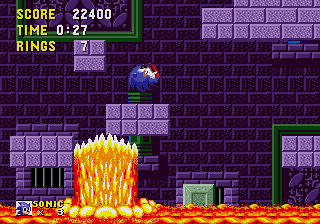

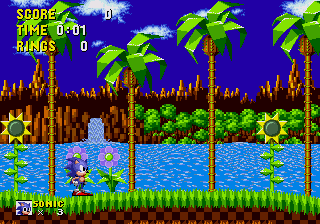

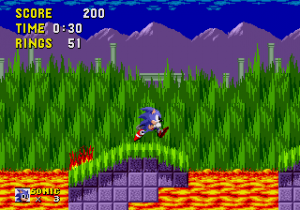

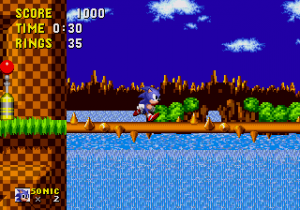

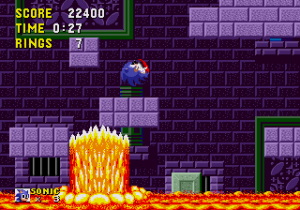

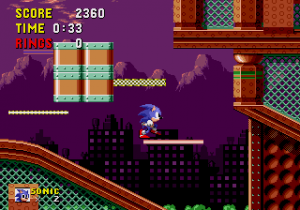

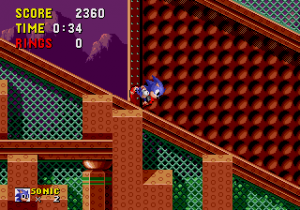

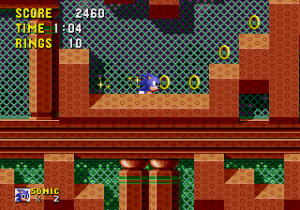

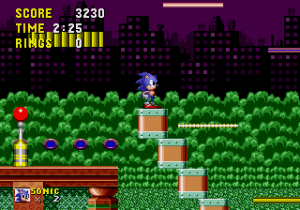

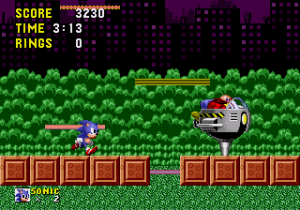

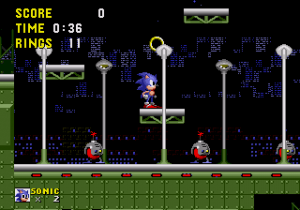

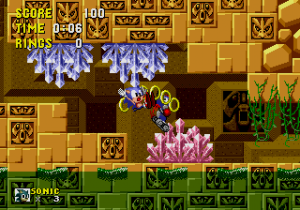

The game is divided up into six “zones”, each with three levels. The game starts in the sunny Green Hill Zone, before moving to the underground, lava-filled corridors of Marble Zone, then to the pinball bumper-filled playground of Spring Yard Zone. The back half of the game consists of the flooded ruins of the Labyrinth Zone, the dazzling, night-themed Starlight Zone, and finally Robotnik’s base, Scrap Brain Zone. At the end of each level, you fight Robotnik himself, each time piloting a different evil contraption, giving him a recurring presence in the game instead of sitting at the end like many video game villains.

One of the biggest appeals of Sonic the Hedgehog is, of course, the speed. From a technical standpoint, this is where Yuji Naka’s programming prowess was demonstrated. Mario could always run in his games, but it was never something you did for long, since the main goal was to jump over pits and avoid enemies. That element is still in Sonic, of course, but there’s a much greater emphasis on giving places for the eponymous hedgehog to show off his speed. The levels are filled with not only long flat planes, but also hills, slopes, and most impressively, loop-de-loops giving the game a more dynamic landscape than most other platformers. Plus, while other games had simple physics systems that implemented inertia, Sonic is much more complex, especially since the central gameplay relies on it. Sonic can’t quite build up to high speed on his own (at least in the original version of this game), so he needs, at bare minimum, a running start, but can go even faster via the springs and curves that are placed judiciously around the landscape.

Furthermore, the levels are gigantic, with extremely high vertical space. Though it changes on a level-by-level basis, many stages are quite open ended, with different paths in the high, middle, and low parts of the stage. And even the levels that aren’t as open typically have branching paths. Each level not only has a ton of hidden stuff, but it lends greatly to the replay value, since you can take any route you want, at least in the stages that allow it. Power-ups are kept in destructible monitors, including ring bonuses, extra lives, shields (which let you absorb a single hit), speed boots (which temporarily let you run even faster) and invulnerability. There are also checkpoint posts littered generously throughout each level, indicating where you’ll restart if you die.

One of the game’s other big innovations is the damage system. Like Super Mario Bros., the levels are littered with collectibles, though here they’re rings rather than coins. Grab 100 and you get an extra life, but they serve an even more important function – as long as you have at least one ring, you can’t be killed, at least by an enemy. Take damage and Sonic will drop them all, scattering them all around the screen, letting you pick them up if you can reach them. (Obviously, if you have more rings, it’s easier to grab more of them, but if you had only one or two, they’re harder to re-collect.) It solves one of the central issues with the game’s speed – that is, there’s always the chance that you might run too fast into something you can’t see. It also reconfigures the platformer formula by allowing you to attack more aggressively than other similar games, since you almost always have some kind of safety net. Conversely, in the few moments where you don’t (or can’t) get any rings lends a sense of urgency and vulnerability.

Along with this are other subtle ways that makes Sonic more powerful than other platforming heroes, even if he still can’t attack directly. Since he curls into a spiked ball when jumping, you don’t necessarily need to jump on top of an enemy, you just need to touch them. Sonic can also curl up when running, allowing him to buzzsaw through enemies on the ground (at the expense of building up extra speed). Of course, some enemies have spikes themselves to defend them against such assaults, so it’s never quite too easy. The Genesis version doesn’t offer any save game function, and continues are limited, but there is a level selection screen if you’d like to jump around.

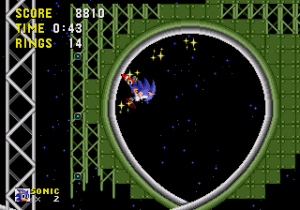

In addition to beating the levels, there’s also a secondary goal of finding the Chaos Emeralds. If you beat a stage with more then 50 rings, than a gigantic ring appears above the sign that marks the stage’s end. Jump in and you’ll reach the bonus area, a spinning arena with trippy backgrounds and hypnotic music. These are often simple mazes, with passages that lead to dead ends, sending you back into the main game. Here, you’re working against the constant rotation of the level, destroying walls and bouncing off bumpers. In addition to rings, there are also little indicators that can speed up or slow down the mazes, or even reverse its rotation. At the end is the Chaos Emerald – if you manage to get all six of these by the time you beat Robotnik, you’ll unlock the best ending. Naturally, this is an incredibly difficult task, because navigating these stages takes a huge amount of practice, and there’s not a lot of margin for error.

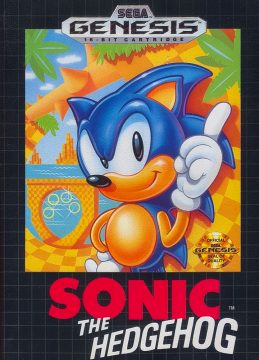

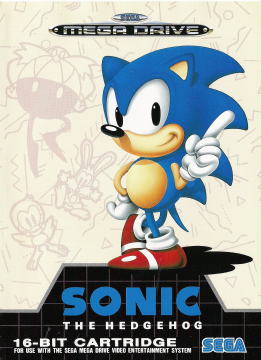

Of course, much of the appeal of the game lies on both the characters and the visuals. Sonic shows a remarkable amount of personality for a video game character – he teeters worriedly at the edges of cliffs, he gets annoyed when the player lets him set for too long, and he gives his characteristic finger wag when beating a level. It made him seem “cool” to an audience that was getting slightly older and growing out of more broadly cartoony characters like Mario. So in that end, he was a perfect foil. The robotic enemies, similarly, exude both a sense of cuteness and dangerousness.

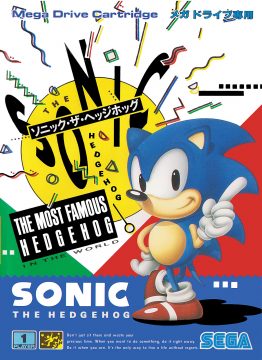

The Japanese cover for the game has a pop-art feel to it, with a white background with various shapes and colors. This theme never appears in any of the games, but the same basic kind of style can be seen in little background details, like the angular leaves of the palm trees or the checkerboard ground of the Green Hill Zone. Indeed, the fact that there are six completely distinct levels, with various styles and color palettes (the green flora and light blue skies of Green Hill, the dark blue bricks and red lava of Marble, the pink backgrounds and lights of Spring Yard, and so forth) sets it apart from the fairly repetitive look of the Super Mario Bros. games. The parallax scrolling is also many layers, acting as one of the major showcases for the 16-bit power of the Genesis.

The music is composed by Masato Nakamura, the bassist and producer of the J-pop band Dreams Come True. Like the color palette, each level has a distinct tone and mood, from the peppiness of the opening area to the more mechanical foreboding songs in the final area. The sound effects are just as important, particularly the iconic cash register sound at the edge of each level, taking Sonic’s rings and turning them into points.

For a first entry in a series, that would go on to birth dozens of sequels and spin-offs, Sonic the Hedgehog is surprisingly well formed. But, there were a few areas where the game slightly falters, as the developers hadn’t quite gotten a handle on the game’s design. The biggest fault is the inconsistent pacing of the levels. Green Hill Zone is a brilliant first area, because it shows off all of what Sonic can do. And the best levels are the ones that seamlessly blend the times where Sonic is running and jumping over enemies, or the times where control is basically wrestled away from the player, sending them on a roller coaster ride throughout the level. But the second area, Marble Zone, contains absolutely none of this, just walking beneath spiked traps and sitting on bricks floating in lava. Spring Yard Zone gives lots more areas to play around, but the dreary Labyrinth Zone takes place mostly underwater, where Sonic’s speed is not only drastically slowed, but requires finding regular bubble pockets to restore his air. Starlight Zone is, again a return to form, as is most of Scrap Brain, but the third act of the penultimate level takes place in yet another variation of the Labyrinth Zone, which sucks the fun out of what would otherwise be an exciting climax. The game also curiously makes you fight the final boss with no rings whatsoever, making this battle substantially more difficult than all of the rest.

Ultimately, the problem with giving the game such sensory rushes is that the slower moments feel really boring in comparison, even if they’re perfectly fine by the standards of other platformers.

The other notable issues, which is a problem in pretty much every Sonic game, is that it is quite buggy. While it’s not pervasive, it is possible to get caught in, or drop through, the scenery, sending you to unfortunate deaths through no fault of your own.

Still, most of these are only considered problems in retrospect. At the time of release, Sonic the Hedgehog was enormously popular, garnering accolades from press and gamers alike. It also became the pack-in for the Genesis, a smart move on the behalf of Sega of America President/CEO Tom Kalinske. When it was initially released in 1989, the pack-in was Altered Beast, which was a good selling point to show off the system’s arcade ports, but not exactly the type of software you’d use to sell the console to kids (or their parents). From here on out, Sega finally had not only a true counterpoint to Mario, but the “cute but edgy” personality that helped define the console for the rest of the generation

Sonic the Hedgehog was actually launched first in North America, giving the developers a little more time to polish up the game for its other releases. Particularly, in the Green Hill Zone, there are more clouds in the background, and they scrolling independently of Sonic. The initial release also has a glitch where invincibility periods don’t apply to spikes. This results in many cases of players falling into spikes, bouncing onto the spikes next to them, and then immediately dying, rather than getting a chance to regain any rings. This was fixed to prevent this from happening.

There’s also a slightly different version of the game released for the Mega Play arcade hardware. Changes include the removal of Marble and Labyrinth Xones, as well as the third act of Scrap Brain (the slower ones), as well as the bonus stages, plus the ability to get extra lives via monitors is gone. Each level also has a specific time limit, requiring that you run through each stage as fast as possible. All of these tweaks were done to make the game harder, especially since the player can get extra lives by inserting more credits. There’s also an added high score screen.

Most subsequent releases of Sonic the Hedgehog are emulations of the Genesis game (not counting the Game Gear and Master System versions, which are totally separate games). There are some exceptions, though. The version featured on the Sonic Jam compilation for the Saturn adds in a Spin Dash, like the one found in Sonic 2 and other later games. This feature was also added to the 3DS port by M2, which, like all of the other games part of the Sega 3D Classics line, adds in 3D support for the parallax backgrounds. The Nintendo Switch port is based on this (without the 3D, of course) but adds in the drop dash ability from Sonic Mania, and includes the Mega Play version as a bonus.

The Game Boy Advance version is one of the most dreadful ports of all time. For starters, all of the visuals were ported over directly from the Genesis version. While there were three other Sonic games for the Game Boy Advance, these were all original titles that scaled the characters down for the smaller screen. Since this game doesn’t, Sonic is simply much too large, and the playing field is too cramped, a huge problem in a game where you need to see what’s around you.

This is compounded by the fact that the game is extraordinarily glitchy, and barely ever functions at full speed. It also sounds really, really terrible. The game does record any level you’ve beaten and lets you start at later ones, but it doesn’t actually save your game, like the number of emeralds you’ve obtained. Altogether, despite looking okay in screenshots, it’s also almost entirely unplayable.

The best port is the mobile release, published for iOS and Android platforms in 2013 and developed by two long standing members of the Sonic Retro fan community: Taxman (Christian Whitehead) and Stealth. Taxman had basically created his own Sonic the Hedgehog engine from scratch and came into an agreement with Sega to use it to officially port games to other platforms. Not only does it perfectly replicate the original game, but it adds in proper widescreen (since it’s not just emulating the Genesis game) and numerous features from subsequent games, including a spindash, the ability to play as Tails and Knuckles, the ability to unlock Super Sonic, and an expanded debug mode that includes some stuff that was planned but never implemented in the final game, like the goggles that let you breathe underwater. A few tweaks have been made to the boss fights and levels too, primarily to add in a few extras paths (for areas that only Tails or Knuckles can take into reach) or take into account the added difference in screen space. It also fixes up some bugs and runs smoother than the Genesis version, adds a save game function, and lets you change between the physics from the later games. It’s a brilliant port, the perfect way to update a retro game for new technology while keeping its core, and it’s baffling it was not made available for other platforms.

Screenshot Comparisons