There’s been a growing resentment with some aspects of the indie game scene in communities lately. Some people feel that the creators’ artistic ambitions (or pretense?) celebrated in the mainstream and indie outlets tend to distract from the actual gameplay. Despite most of these games harken back to the good old days when video games were made out of blocky pixels, the verdict is often that there’s a lack of respect for design traditions, replacing them with countless cheap deaths – cheap in both the ways they are inflicted and in their consequences. Stylistical clashes like blocky sprites and backgrounds with high-res effects or similar disregard of authenticity are frequent probable cause to assume “retro throwback” doesn’t mean more than a bad excuse to put as little work as possible into the graphic assets.

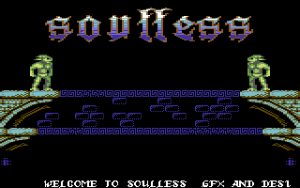

But then there are the developers who go the extra mile not only to make the games look and feel like the kind of games we played in our childhoods, but even make them run on the hardware we’d have played them on. One of the institutions dealing in real retro throwbacks is Psytronik Software, producers of such modern Commodore 64 classics as Sceptre of Bagdad, Psyko Zone and Joe Gunn. Now the latter game’s programmer Georg Rottensteiner has teamed up with Trevor Storey, who already did the title artwork for Joe Gunn, to create the latest Psytronik release: Soulless.

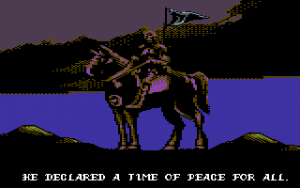

The result is a honest-to-god explorational platform game that could just as well have existed in the C64’s heyday. Beginning with the story told in the animated intro, there’s no nebulous artistic message, only refreshing ’80s simplicity: The good king declares “a time of peace for all,” which pisses off his plainly evil right-hand wizard, who rips out his soul, turns him into a beast and throws him into the dungeon. After a thousand years, the former king finally sees an opportunity to escape, but before he can retake his country, he needs to regain his soul.

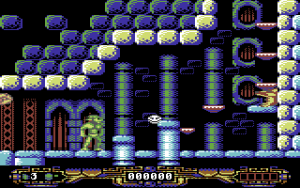

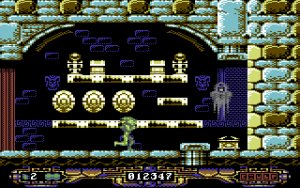

However, the precious thing is inconveniently torn apart into twelve pieces, which are scattered around the catacombs, so the monster/king has to look inside every nook and cranny to get them back. The search takes a while per item, but not only reveals the uniquely painted Spirit Stones, but also other useful stuff like gold and jewels (which accumulates to the old-school high score), and a number of instant magic effects that grant temporary invincibility, freeze enemies or rid the screen of them entirely. When all twelve are gathered, they have to be brought to the Soul Chamber and put into the correct order, hints to which are painted on the dungeon walls here and there.

Some paths can only be unlocked with the right key (also notice the different life bar in this promo shot)

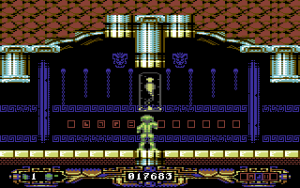

The map might not be as “massive” as the promotional bullet-point features would have one believe, but still big enough to get lost in. A perfect player could still beat the game in less than an hour, but getting there is a long way. It begins with mastering the jumping mechanics, which are done the old-school, hardcore way. Like in classic Castlevania or Ghosts ‘n Goblins, everything is said and done as soon as the player sprite is airborne, then all that’s left is hoping the jump is timed and placed right. The king also has no means to fight the monsters that lurk in almost every room, side from the aforementioned spells. And even then they respawn, unlike the containers that might or might not hold the spell.

Items, as a matter of fact, actually are in different places with each playthrough, as they are randomized. So as soon as one runs out of the sparse reserve of extra lives, the stones and clues have to be found all over again. The one concession Soulless makes towards modern game design philosophy are the instant respawn points that also heal the player (who takes six hits to kill), but they’re only good as long as there are lives left. All this doesn’t quite make Soulless “Nintendo-hard,” but it’s no walk in the park, either.

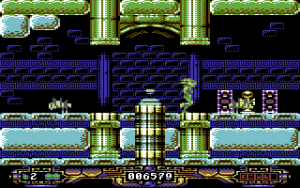

Of course, it is always easier to make a game look and feel like the real deal if it is the real deal, but the graphics Soulless does an excellent job of capitalizing on the strengths of the hardware while downplaying its weaknesses, and look leagues better than most other games Psytronik Software has put out for the C64. The soundtrack likewise makes a good case on why it had to be created in SID format. Aside from the intro and ending, it’s always the same track throughout the game, but that one is incredibly long, so one hardly notices it looping back from the beginning, and it gives a nice impression of continuity.

All this makes Soulless for once a genuine throwback to the good old days of classic gaming. It relies on traditional, simple mechanics that don’t wear off even after 25 years, unlike the gimmicks of some other “progressive” indie platformers. The level design does nothing that’ll make anyone shout out “genius!”, and typically for this kind of open-maze exploration game can never hope to provide a steady difficulty curve, but it’s functional, challenging and – with the exception of two aggravating rooms full of instant deaths – remains always fair.

To make things as comfortable as possible, Soulless is available for every thinkable C64 storage device. Binary Zone sells the Floppy and Tape versions at various price points, while the game is even available on cartridge at RGCD, which is the most expensive variant but also spares one the initial loading time. It’s especially impressive since that format is currently limited to only 64KB storage space. Every purchase comes with a free digital download to play in an emulator or copy to whatever device to play on a real Commodore, which can also be bought standalone for no more than 1.99 British Pounds. The “Premium Edition” variants all come with a map, short comic/manual and a companion CD full of behind-the-scenes material and other goodies.