- Spyro the Dragon

- Spyro 2: Ripto’s Rage

- Spyro: Year of the Dragon

- Spyro: Reignited Trilogy

After the success of Ripto’s Rage, Insomniac started producing another sequel, but found themselves becoming increasingly constrained by the limitations of the Spyro character; unsure of how to meaningfully improve on a gameplay style they’d been working on for four years. While Year of the Dragon is very good, this would explain why it has a more scattershot focus, with an emphasis on new playable characters and minigames that won’t appeal to everyone in the same way.

Once every twelve years, the Dragon Realms celebrate the “Year of the Dragon”, when dragon eggs are brought to the kingdom. One sleepy morning, a rabbit named Bianca and a band of Rhynocs appear from holes in the ground to steal the eggs. While the dragons soon wake up, they can’t stop all 150 eggs from being taken to the Forgotten Realms, a region on the other side of the world ruled by the Sorceress. The holes are too small for the adults, so it’s up to Spyro and Hunter to head to the Forgotten Realms, rescue the eggs, and defeat the Sorceress if they must.

Year of the Dragon retains the same gameplay, but changes things up. Enemies drop gems again, and power-up gates are always active. The main collectable are Dragon Eggs, which are earned by helping people out, exploring, completing minigames, and more. Levels are accessed through four hub worlds, with each one featuring four Spyro levels, a speedway, an ally level, and a Sparx level. To reach the next hub, you have to beat Spyro’s worlds and the ally world, which will prompt their residents to build a vehicle to take you there. However, some worlds are inaccessible unless you collect enough Dragon Eggs.

Spyro controls the same, and doesn’t have any new moves to unlock. Instead, the focus is on new characters and their playstyles. In each hub world, you’ll find an ally who’s been jailed by Moneybags, who you have to bribe with gems to release. After that, you can play as them in their own worlds, along with designated areas in Spyro’s levels. Sheila uses her enormous feet to jump great heights and give enemies a good kicking; Sgt. Byrd flies around freely and fires rockets at anything in his path; Bentley whacks enemies with his powerful club; Agent 9 runs about and shoots wildly. You can also play as Sparx in top-down shooter levels unlocked after beating the boss in each hub world, which give him extra abilities to help you in regular gameplay when beaten.

Combined with a greater variety of minigames (including Tony Hawk-styled skateboarding stages), there’s a lot more non-Spyro gameplay. While this was likely based on Insomniac not knowing what else to do with Spyro, it might’ve also been inspired by the trend of including several gameplay types in 3D platformers at the time (e.g. Crash Warped, Sonic Adventure). However, Year of the Dragon is by far the best of these games.

Firstly, the new playstyles are largely good. Sheila and Bentley are satisfyingly brutal, Sparx’s stages are simple but fun, and plenty of the minigames are enjoyable while iterating on their ideas for new challenges. That said, Agent 9 and Sgt. Byrd feel awkward to move and aim, while some minigames suffer from being clunky and underdeveloped. While they’re overall not as good as Spyro, they thankfully never take precedent over him.

It helps that you still play as Spyro mostly, and can even skip many of the other playstyles. While you do have to beat the ally world in the first three hub areas to progress, you only need 100 eggs to fight the Sorceress – something that can easily be done as Spyro, though you have to be very diligent about finding every egg. This is a big improvement over games like Crash Warped, which forced you to trudge through every gameplay type to get to what you wanted to play.

This freedom also extends to collecting the Dragon Eggs. Because they’re the only major reward, you’re allowed to approach levels however you like. You can find every egg, or you can only get eggs through your preferred mechanics, and there’s plenty around if you get stuck. Even the Speedways do this, with challenges now giving you eggs. However, you’re still restricted in how much you can do at any time, since you have to beat the Spyro and ally worlds to progress. Needing eggs to unlock worlds does give you the interesting choice to either collect what you like but have less to explore, or find everything to give yourself more options earlier on.

Unfortunately, this makes the structure much more repetitive. Like the first game, you end up doing the same things in each hub world, which can get especially tiresome if you like finding everything. The level-to-level structure can be fairly varied, with some stages focusing on minigames while others emphasize exploration. However, the designs themselves lack the variety in linearity and objectives its predecessor had, but without the original’s platforming.

In an attempt to address criticisms of Ripto’s Rage being too easy, Insomniac implemented a dynamic difficulty system, where many variables subtly change depending on your performance. The game becomes harder if you’re very good, and eases up if you’re having a tough time. It’s a nice touch that lets the player tackle the game in a way that suits their ability. This does mean that the game can’t tell you how tough challenges are going to be, which can result in a sudden difficulty spike. However, you don’t lose lives in these sections, allowing you to try them as much as you want without consequence.

While most changes are divisive, one area that feels like a definite downgrade are the boss fight. They still employ changing attack patterns, but most of them aren’t that challenging, and some of the strategies are a bit too repetitive. This is especially the case for the final boss, which should be an exciting climax but instead feels throwaway. The greater emphasis given to the post-endgame doesn’t work either, since the rewards for finding everything are equally unsatisfying. It weakens what’s otherwise a very good Spyro game that sacrifices some strengths to make for variety.

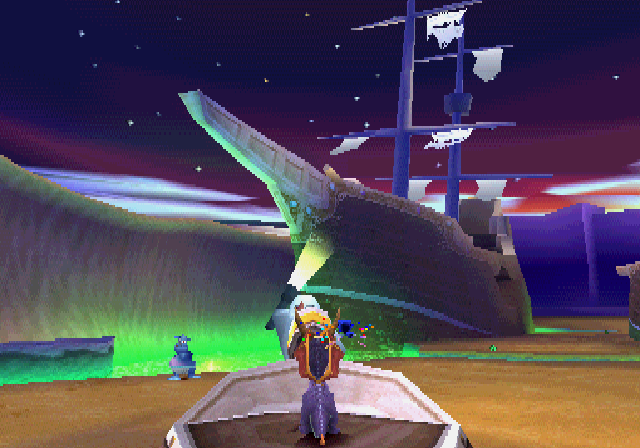

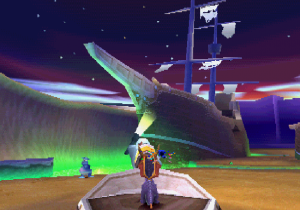

The graphics are still impressive and gorgeous, but what stands out this time is the use of color. Worlds and even select locations are given striking color schemes with a particular focus on gradients to create beautiful, somewhat melancholic locales. This helps to alleviate some of the more uninspired levels such as Bamboo Terrace and Haunted Tomb, which use generic fantasy themes. The character designs are still charmingly expressive, though they’re a bit more esoteric this time (something likely influenced by character designer Oliver Wade’s request to not redo any designs, since he was heavily involved on what became the original Ratchet & Clank).

The soundtrack is once more done by Stewart Copeland, but TV composer Ryan Beveridge also contributes a few tracks (likely to lighten Copeland’s workload, which was also occupied with the music for Alone in the Dark: The New Nightmare at the time). Beveridge’s involvement, along with the inclusion of new loops and samples, give Year of the Dragon a sound distinct from the previous games. While a lot of the instruments and melodic sensibilities return, the way the tracks are written provides an upbeat, but often eerie mood that makes certain levels more powerful. However, some tracks focus too much on having a unique sound, and become grating after a while (Sgt. Byrd’s theme is the worst example of this).

The music was lacking in the game’s original US release, which was rushed to tie into the Chinese zodiac year Year of the Dragon was named after. Along with a number of glitches, some of the tracks had to be re-used in a couple of levels (a first for the series) because the songs intended for them weren’t put in on time. One peculiar glitch is that the final boss uses the theme of the first home world, which creates a baffling dissonance. These issues would eventually be corrected in the Greatest Hits re-release, although the European versions still had to remove some of the songs in order to make room for the non-English language tracks (this also impacts the audio for the cutscenes, which have been heavily compressed).

The story is better in some aspects than Ripto’s Rage and worse in others. The dialogue is much improved with a lot of genuinely funny lines, which is bolstered by a solid voice cast including Pamela Hayden (best known as the voice of Milhouse from The Simpsons), Neil Ross, Carolyn Lawrence, Richard Tatum and Edita Brychta alongside returning actors. There’s an attempt to develop the characters through the cutscenes, and Bianca gets a particularly compelling arc. But the sense of community from before is gone, with levels feeling very disconnected and a lack of opening/ending cutscenes to provide context. Characters do refer to other worlds, and some characters from previous games even return, but it’s not enough to make the Forgotten Worlds feel as investible.

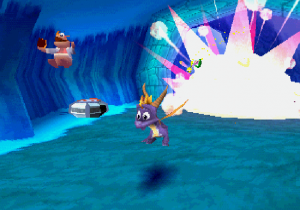

Like many games at the time, Year of the Dragon employed anti-piracy measures to prevent pirates for cracking it and selling illegal copies. However, this game is infamous for having an extensive crack protection that was very difficult to overcome, and the effects that triggered if anything off was detected. Select collectibles would either vanish or constantly reset, and travelling would frequently take you to the wrong place. Bigger changes include the game regularly soft-crashing and not being able to pause, while the language constantly changes in the European version. Most notoriously, it crashes on the final boss battle and wipes your save data, similar to EarthBound. It took over two months for a correctly patched version to be made, which was an impressively long time considering how most games normally took a week or two to crack back then.

Year of the Dragon was the last Spyro game developed by Insomniac, who moved on to create the Ratchet & Clank games for the PS2: a series that developed some of the concepts introduced here such as a third-person platformer/shooter while introducing new ideas to make for a distinct series. The rights to Spyro remained with Universal Interactive, who went on to commission several developers in creating more games over the next decade, though it’s largely considered that none of them hit the same highs as the original trilogy.

(The screenshot from the cracked version was sourced from Geek.com: https://www.geek.com/)

LINKS:

An article on Gamastura by Gavin Dodd detailing the process of creating the anti-piracy crack protection, its effects, and how it could be improved: https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131439/keeping_the_pirates_at_bay.php

A list providing most of the common effects caused when triggering the anti-piracy crack protection: https://tcrf.net/Spyro:_Year_of_the_Dragon#Anti-Piracy