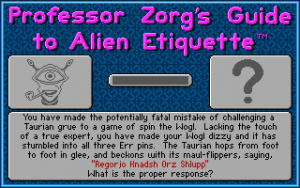

The Star Control series, published by Accolade but primarily created by Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford, is known for a few things things: its deep lore, a comical cast of aliens, and its combat system. The story imagines an intergalactic war between two factions: the Alliance of Free Stars (the good guys) and the Ur-Quan Hierarchy (the bad guys). Within these factions are a number of races, each with their own unique starships. Each race has a detailed backstory of its own evolution, how it discovered space travel, and how they first dealt with discovering life outside of their own planets. Some of it is based on classic science fiction and lore – there are elements of Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica, plus the inclusion of the classic “grey” aliens, whose origins go back to the 1950s – but the galaxy is also filled with other strange and bizarre species, ranging from kamikaze foxes to religious spiders. Most of the best parts of this universe shine through with the second game, which features numerous dialogue sequences, and a much stronger storyline.

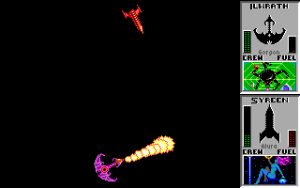

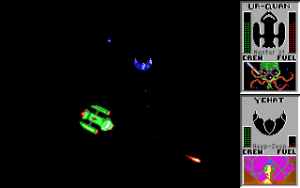

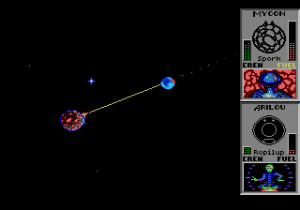

The other draw of Star Control is its “melee” battle system, heavily inspired by the classic game Spacewar!, and its many offshoots. Combat is one-on-one, viewed from an overhead perspective, as each ship tries to outwit, outmaneuver, and destroy the other. The space field is vast, but zooms in and out whenever the two ships approach or retreat from the other. Each playing field also has a planet, with its own center of gravity, which can be harnessed to slingshot your ship around the arena. This is fairly important, as each ship has its own speed, and this is often the only way for slower ships to catch up with the faster ones. You can also crash into the planet and suffer significant damage, if you’re not careful.

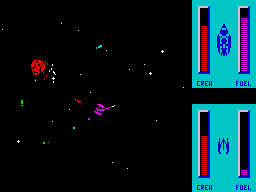

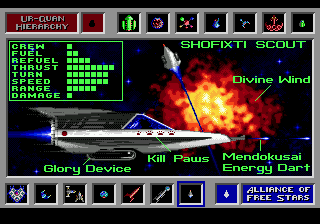

Each ship has two weapons, typically a standard, forward firing attack, and some kind of secondary ability. Most of these are powered by a separate “battery” meter, which recharges automatically (with some exceptions). Your ship doesn’t have traditional HP or shields, but instead its health is determined by the number of crew members. The logic is that each impact will kill some of its staff; when none are left, the ship is abandoned and therefore destroyed. This is designed to accommodate the colonization aspects of the first Star Control, where members of each base were used to re-staff damaged ships, but some vessels use this in creative ways. For example, the Ur-Quan Dreadnought can launch little jet fighters, each piloted by a crew member to home in on their opponent and pelt them with tiny lasers. They can be killed, though, so essentially you’re sacrificing a small amount of your “life” meter for a special attack.

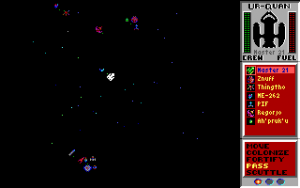

There are a number of details that add character to the ships, particularly the randomized names given the captain of each vessel, and the little status window that shows the pilot controlling it (and exploding when they’re killed). The humans are named after assorted science fiction characters, the fox-like Shofixti are given Japanese names, the crystalline Chenjesu have various combinations of “brzzz” and “zrrr” sounds, and the evil, caterpillar-like Ur-Quans are simply assigned numbers. Each race has their own little victory theme, too.

There are three games in the Star Control series: the first is a strategy game, while the second and third defy traditional genre classification, though they’re the closest to an RPG. There were numerous planned sequels that were eventually canceled, with assorted reboots currently in legal hell.

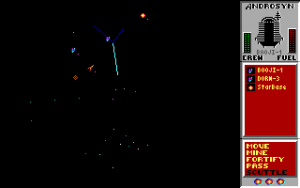

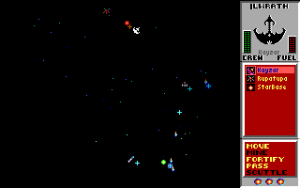

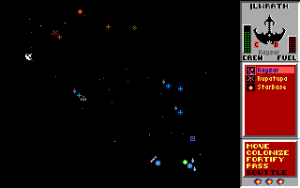

The first Star Control is actually somewhat similar in concept to one of Reiche III and Ford’s earlier games, Archon, in that it’s a strategy game where conflict is resolved via action-based one-on-one combat. (It could even be termed a spiritual successor, given that it’s even in the title – “StAR CONtrol”.) However, the strategy here is fairly straightforward. Each game begins with two players on opposing sides of the map. The goal is to work your way across the galaxy, claiming the planets along the way, and eventually destroy your opponent’s starbase. You can only make three moves per turn, regardless of how many ships you have. On each planet, depending on what type it is, you can colonize it, mine it, or fortify it. Colonies will provide reinforcements for your ships, while mines will provide extra “starbucks”, which are used to create new ships at the home base. Fortifications are used to prevent the opposing player from passing too far into your territory. When two ships meet, then they enter melee combat.

One of the most important things to remember in Star Control is that the ships are not at all balanced, owing to way the economy works in the strategy segments. The more powerful ships, like the Ur-Quan Dreadnoughts and Chenjesu Broodhomes, can steamroll over most others, because they’re the most expensive. That doesn’t mean the weaker ships are totally worthless, though, because the Syreen and Spathi ships, in particular, can be extremely damaging in the right hands, due to their special powers and maneuverability. The sides are not really equivalent either – there’s a solid argument to be made that the Hierarchy ships are, generally, better than the Alliance’s.

There’s not much structure to the game. There’s no campaign mode, just nine scenarios to play through, each with a brief written introduction. You can pick which side to play as, though. When one side win, there’s a victory screen, and then it’s back to the main menu. There is a scenario creator, but there’s not much variety to the type of missions you can create anyway.

As a strategy game, there’s not much really wrong with Star Control. The only real hassle is the fact that the stars on the map constantly spin around, making it difficult to tell where they are in relation to each other, until you try to move. But it’s just not particularly exciting either – it’s really too simple to become invested in. Instead, it feels like the strategy section just provides context for the melee battles. In two-player mode, it’s a lot of fun, but in single player mode, it’s pretty dull. It doesn’t help that the series really came into its own with Star Control II, largely thanks to its strong story and writing. This game has almost none of that, outside of what’s in the manual and the short pre-mission blurbs. There’s no background music either, and other than the sound effects and victory songs, most of the game is played in silence. As a result, it really just feels like a stepping stone to bigger and better things.

As a strategy game, there’s not much really wrong with Star Control. The only real hassle is the fact that the stars on the map constantly spin around, making it difficult to tell where they are in relation to each other, until you try to move. But it’s just not particularly exciting either – it’s really too simple to become invested in. Instead, it feels like the strategy section just provides context for the melee battles. In two-player mode, it’s a lot of fun, but in single player mode, it’s pretty dull. It doesn’t help that the series really came into its own with Star Control II, largely thanks to its strong story and writing. This game has almost none of that, outside of what’s in the manual and the short pre-mission blurbs. There’s no background music either, and other than the sound effects and victory songs, most of the game is played in silence. As a result, it really just feels like a stepping stone to bigger and better things.

The IBM PC and Amiga versions are pretty closes to each other, really only different in minor visual and audio elements. The Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum version are drastically simplified. Beyond the downgrade in graphics, the battle scenes are missing the planets. In the Commodore 64 version, the status bar is moved to the bottom of the screen, but the view is still fairly large. In the Amstrad CPC version, the status bar chews up about a third of the screen. Considering the 8-bit hardware, these ports are alright, but they’re definitely the inferior versions.

Star Control was also ported to the Genesis. Graphically, despite the console having a lower color palette than the 256 VGA DOS version, it looks almost identical despite slightly less colorful ships – most of the game is just the black background and grey interface anyway. It was the first 12 megabit cartridge released for the system, and most of that space seems to have been devoted to sound effects, which were then re-used for Star Control II. Since there is no battery backup, the scenario creator is gone, though there are a handful of extra ones that were added. Unfortunately, there’s significant slowdown in the melee segments, marring the best aspect of the game. According to the developers, they were given no time to optimize this part, which they were disappointed with.

Star Control was also ported to the Genesis. Graphically, despite the console having a lower color palette than the 256 VGA DOS version, it looks almost identical despite slightly less colorful ships – most of the game is just the black background and grey interface anyway. It was the first 12 megabit cartridge released for the system, and most of that space seems to have been devoted to sound effects, which were then re-used for Star Control II. Since there is no battery backup, the scenario creator is gone, though there are a handful of extra ones that were added. Unfortunately, there’s significant slowdown in the melee segments, marring the best aspect of the game. According to the developers, they were given no time to optimize this part, which they were disappointed with.

Screenshot Comparisons