Great games often come from humble beginnings. Indie designer Edmund McMillen created Meat Boy, a tough-as-nails platformer with a retro aesthetic, and released it for free on the popular flash website Newgrounds in October 2008. Within six months the game received nearly one million views and inspired a larger and more ambitious project. Programmer Tommy Refenes joined McMillen to form developer Team Meat, and the two tirelessly worked on Super Meat Boy, an expanded version of the original flash prototype. When the game hit Xbox LIVE Arcade in October 2010, just two years after Meat Boy’s debut, a new indie sensation was born.

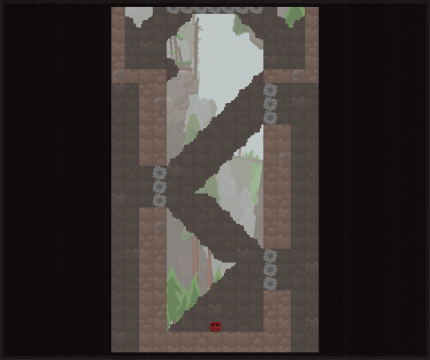

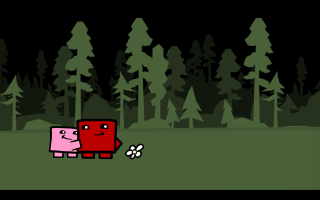

On the surface, Super Meat Boy doesn’t seem particularly special. The game stays true to the platformer genre – players merely run and jump to reach Bandage Girl and in turn the end of each level, but much of the game’s brilliance lies in its simplicity. One needs to only play Super Meat Boy for a few short moments to understand how it operates and what it asks of the player. The lack of extraneous content allows the straightforward mechanics to shine. It also allows McMillen and Refenes to focus their efforts on insidious level design that gets at the core of Super Meat Boy.

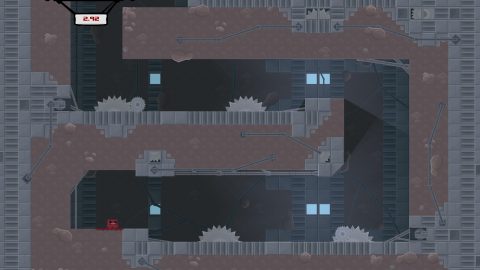

Plenty of Super Meat Boy discussions address the game’s difficulty, and it clearly offers a challenge like few modern-day releases. Players must avoid buzz-saws, homing missiles, and the most dangerous obstacle of all – salt – in order to complete each level. The death count rises higher and higher by the minute, but Super Meat Boy doesn’t confuse challenge with frustration. It uses old platforming classics such as Ghosts ‘n Goblins and Mega Man as references points, but unlike those games, it eliminates the fear of poor checkpoint systems and frequent game over screens. It’s the ideal case of contemporary meets retro.

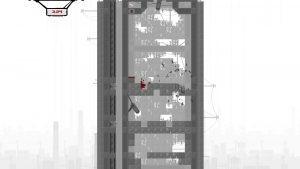

Each level takes roughly 10-30 seconds to complete (with the exception of some late-game content), and a single button press allows players to jump back in following a death. The game also combats frustration with an ingenious replay system that documents every death. There’s nothing quite like the simultaneous joy and horror of watching a hundred Meat Boys die and the ensuing meat juice trail.

Additionally, the difficulty emphasizes the relationship between challenge and progression and its importance within the genre. Super Meat Boy presents a gradual learning curve in content more so than mechanics. Anyone can learn to run and jump within seconds, and the ease of early levels stresses that fact. But when the game introduces new obstacles and more devious level layouts, players must familiarize themselves with the intricacies of the game’s design. An example that immediately comes to mind is the eighth level of world two, which features crumbling walls and a series of small platforms surrounded by slug-like enemies. The first instinct is to play it safe and carefully navigate the level, but if the player constantly holds the run button and pushes forward at a steady pace in the first half of the level, they avoid every single enemy. Die enough times and these subtleties become second nature.

Even though Super Meat Boy is an experience with many deaths, the pinpoint precision of the controls forces players to take ownership of their mistakes. Meat Boy can jump long distances, and the level of in-air control provided sits near the top of the platformer genre. That remains the case even when the run button is held down and the game moves at a far more brisk pace. It’s hard to blame any death in Super Meat Boy on the game itself. It signifies a reemergence of challenge in games, a torch carried by other titles such as Dark Souls and Spelunky. Ultimately the games instill a sense of accomplishment in which victory transcends putting X number of hours into a game. It’s a sign of perseverance and genuine skill.

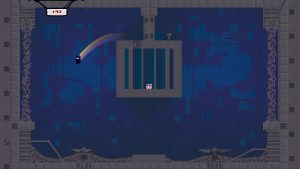

Super Meat Boy also stands out as a content-rich game, with a light/dark dichotomy for its six main worlds. Only light world levels are required to complete the game, but dark world levels provide masochistic twists on the original layouts and pave the way to an alternate, crowd-pleasing ending. Upon completing the game, players are treated to a seventh world – Cotton Alley – which uses a special new playable character.

The XBLA version of Super Meat Boy also features Teh Internets, a hub in which developer Team Meat adds new levels to the game. The company’s tenuous relationship with Microsoft and the needlessly difficult process of adding new content to Xbox 360 releases hindered the full potential of the XBLA-exclusive mode. Instead, McMillen and Refenes focused their efforts on the PC version, which came out in November 2010. It includes Super Meat World, which touts a level editor and incredible user creations. It also introduces The Kids Xmas, a brand new (and very difficult) chapter by Team Meat.

All of the game’s content speaks to the obsessive types out there, as each level includes its own time requirement for an A+ rank. In addition, collectable bandages are strewn across the seven playable worlds, which in turn help unlock new characters. The XBLA and Steam versions of the game include achievements, though the latter has far more. They range from collecting a set number of bandages to beating individual worlds without dying. Most people won’t get a majority of the achievements, but Super Meat Boy is the kind of game that inspires perfection from the most dedicated audiences. It also finds itself as a new staple within the speedrunning community, making appearances at both Summer Games Done Quick (SGDQ) and Awesome Games Done Quick (AGDQ).

Beyond its initial releases, Super Meat Boy was eventually ported to the PlayStation 4 and Vita in 2015, and Wii U and Android in 2016. Performance-wise, they’re solid, and match the Xbox 360 version (though good luck playing the Android version without a controller). Still, there’s one pretty major problemc

The original releases have a fantastic soundtrack. Composed by Danny Baranowsky, each of the songs are perfectly suited to both the intensity and weirdness of the game. There’s a lot of it, too, with different music for the light and dark worlds, as well as their associated world maps, tracks for each boss, and even “8-bit” versions of most of the songs for the “warp zone” areas.

However, due to a falling out between Baranowsky and Team Meat, they were unable to use any of his music in these later ports, requiring them to create a completely new soundtrack. They didn’t cheap out, and got a fair number of excellent composers to provide the replacement tracks, including David Scatliffe (Hotline Miami), Laura Shigihara (Plants vs. Zombies), and Matthias Bossi and Jon Evans (who did the replacement tracks for the updated version of The Binding of Isaac, which ran into the same issue.) The new soundtrack is pretty good, but it doesn’t even come close to the original. Much of it has a different texture than Baranowsky’s signature electronica, with the new track for the first level relying heavily on a banjo, for some reason. The new title theme music is pretty decent, and arguably more appropriate than the original theme, but that’s about the only track that doesn’t disappoint in some way. Had this been the soundtrack from the get-go, it’d probably be well-liked (if not loved), but it’s hard not to think of it as a disappointment.

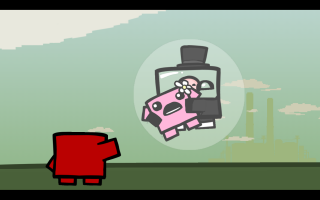

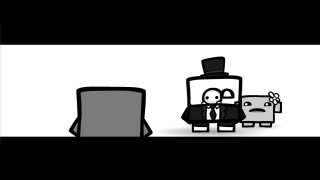

Characters and narrative take a back seat in Super Meat Boy, but they do add to the overall charm of the game. A hunk of meat isn’t the most obvious protagonist, but Meat Boy’s infectious smile and love for Bandage Girl can’t be ignored. Dr. Fetus is an equally absurd adversary – he’s literally a fetus in a glass jar, with a top hat and suit. It’s both amusing and disturbing, and gets at McMillen’s uniquely twisted art style. It also represents the game affinity for sometimes-crude humor, which may turn off some players. One can only take so many poop jokes in the course of 10+ hours.

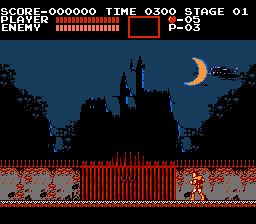

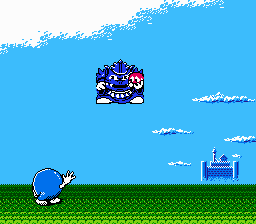

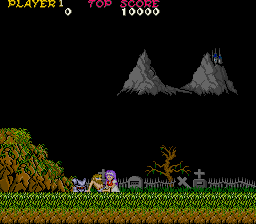

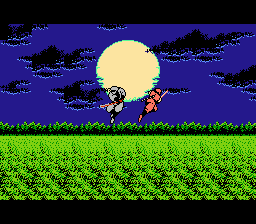

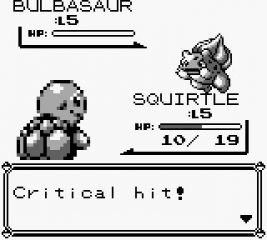

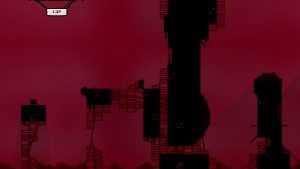

Presentation also establishes Super Meat Boy‘s personality, specifically its retro-inspired visuals and kickass soundtrack courtesy of Danny Baranowsky. It truly feels like playing an old classic in the modern day, right down to each individual pixel and sound. In fact, Team Meat’s obvious reverence for retro classics goes beyond mere visuals and music. Each new world in the game opens up with a reenactment of a famous video game scene. Remember the intro to the arcade version of Street Fighter II? Well that’s the intro to the first world in Super Meat Boy. Other references include Castlevania, Adventures of Lolo, Ninja Gaiden, Mega Man 2, Pokémon Red / Blue, and Ghosts ‘n’ Goblins. The game also features Warp Zones (Mario anyone?), which sport platform-specific art styles. Let’s just say McMillen and Refenes know how to pay homage to their favorite games.

Despite Team Meat’s love of old classics, Super Meat Boy utilizes more than retro influences. It entrenches itself within the history and camaraderie of independent game development. Character unlocks include recognizable names from other indie releases: Alien Hominid, Josef (Machinarium), and Tim (Braid) are just a few examples. Meat Boy, meanwhile, has gone on to star in other indie games as an unlockable character too, such as Dust: An Elysian Tail. These appearances stress the importance of community within indie game development, and showcases Super Meat Boy as an important success story within an entire development scene.

The game’s success proves even more impressive when we consider the old Newgrounds prototype. Meat Boy establishes the basic framework – the titular protagonist, challenging levels, and even some of the music – but the pinpoint precision and excellent level design has yet to emerge. Many opening levels are bland and the keyboard controls occasionally feel unwieldy. In just one year McMillen and Refenes were able to refine that experience and craft something special. Super Meat Boy embraces controllers and excels because of it. Super Meat Boy features environmental variety and devious traps that rival the most satisfying platforming experiences. In short, Meat Boy is a great idea whereas Super Meat Boy is a great game.

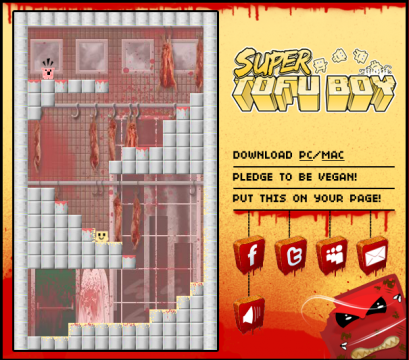

That doesn’t mean Super Meat Boy pleased everyone though. In fact, PETA responded with its own browser game – Super Tofu Boy – in an effort to promote veganism and turn people away from meat. The game promotes such helpful tips as, “Tofu Boy is not only sexy, he tastes great too!” PETA even got Tommy Tallarico to donate music for the game. Team Meat included its own response with a hidden character in the PC version: Tofu Boy. By typing in “petaphile” in the character select screen, players gain access to the worst character in the game. Tofu Boy’s “major iron deficiency” renders him completely useless. Despite being an independent company, Team Meat must have done something right to attract the attention of a big organization like PETA.

Super Meat Boy‘s success transcends indie game development though. It’s one of the best platformers in recent memory, regardless of system, budget, or release method. The retro influences are obvious, but McMillen and Refenes tweak those influences and craft their own singular experience. Only one question remains: will it stand the test of time? Perhaps 20 years from now we’ll look back on it fondly the same way we do with games like Mega Man or Super Mario Bros. Perhaps that’s hyperbole. Let’s reconvene in 2034.