Throughout the 1980s, gory violence in video games was very limited. The controversial 1976 arcade classic Death Race had players run over gyrating stick figures, turning them into little I-shapes. No blood, no gore, just a letter that allegedly represents a tomb stone. The occasional horror text adventure or action arcade game would feature some descriptions of gore or graphical depictions of bloody murders, but for the most part, few existed and they rarely received widespread mainstream success.

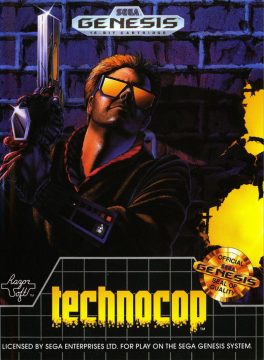

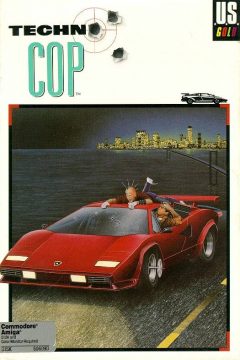

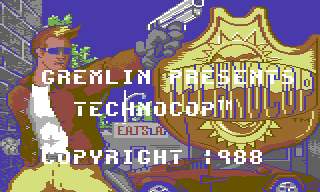

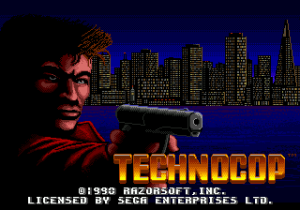

Up until the ’90s, Nintendo of America, controlling the vast majority of the console market in the territory, forced publishers to eschew excessive violence. There are exceptions, but if Douglas Crockford’s “The Expurgation of Maniac Mansion for the Nintendo Entertainment System” teaches us anything, it’s that developers were thrown into a meat grinder. Throughout 1990, the team was forced to make dozens of content alterations while porting the game, including the removal of a pixelated statue that Nintendo thought had visible pubic hair. Crockford, obviously frustrated with the constant revisions, writes that Nintendo’s policies were “not intended to make their products bland, but that [was] the inevitable result.” In 1990, Sega of America had a similar policy to preview games developed for their consoles. However, it wasn’t long before developers figured out just how relaxed Sega’s Seal of Quality was in regards to graphic imagery, with RazorSoft quickly getting the okay to release their gory port of Imagexel’s Techno Cop, a PC game that Gremlin Graphics published for every popular European computer in 1988.

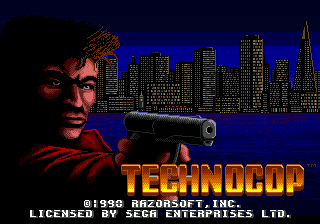

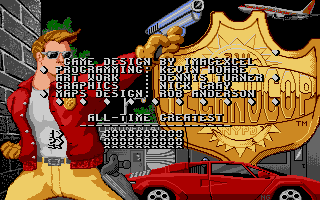

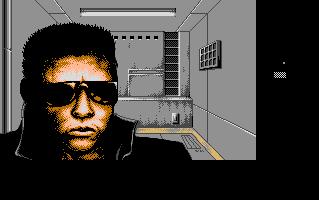

The post-apocalyptic 21st century is a wasteland, filled with mutated punks known as the DOA. Operating outside of eleven dilapidated tenements, their criminal acts are spreading lawlessness across the land. It’s up to a member of the elite Enforcer unit, a Techno Cop, to drive up and down the highways, scour the tenements, and put the DOA leaders out of commission. If Techno Cop sounds like every other action game from 1990, that’s because it is. The game is broken off into RoadBlasters-style driving sequences and mazelike side-scrolling levels, neither of which are particularly original.

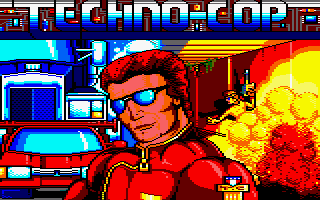

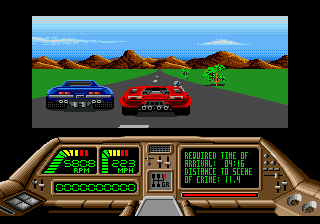

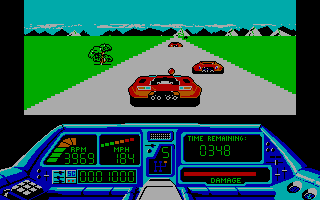

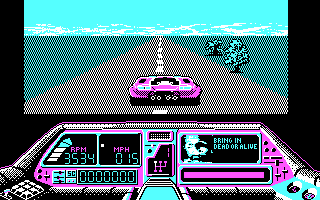

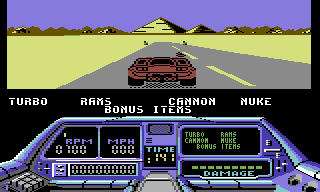

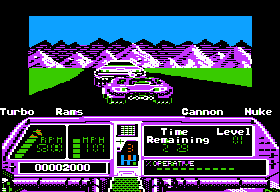

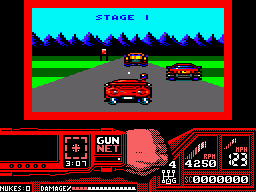

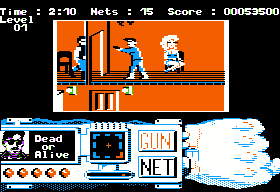

The driving sequences are probably the worst part of the game, although their low difficulty level and simple mechanics do help break up the more difficult mazes. In these portions, the player must drive to the next DOA hideout while avoiding foes. Enemies are limited to small cars and big trucks to blow up or run off the road. Occasionally, a DOA member can jump from a truck onto your car, continuously draining your health until they eventually fall off. When diving punks or other vehicles destroy your car, the game ends immediately, a peculiar design choice considering the player is given lives during the side-scrolling portions.

Multiple weapons for the car are unlocked as you progress through the game, including wheel rams, side-mounted guns, and giant mushroom-cloud-generating nukes. There’s also a timer, but there’s no penalty if you take too long. Bonus points are awarded if you reach the DOA tenement within the limit, which is only important when going for a high score.

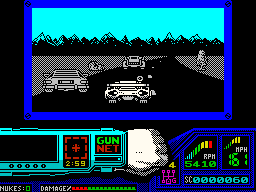

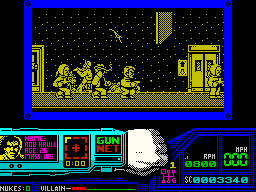

Once you reach the hideout, the real struggle begins. Rushing from the car and into the the building, the player is thrust into an elaborate maze. Navigating this requires the Techno Cop to use his wrist-mounted computer, which functions as a locator. It continuously points an arrow in the direction of the stage’s boss. Even with the extra help, navigation is rough: while the arrow does give a general sense of direction, the levels are very large and filled with countless dead ends.

Elevators are the key to exploration, although they quickly grow frustrating. Some tenements are ten floors tall, and few elevators let off on more than three floors. Every new floor quickly becomes a scavenger hunt for elevators or a gap to fall through. Even worse, holes in the ground are rarely trusthworthy, since Techno Cop instantly dies if the drop is two stories high. Without a proper way to move the camera down, it’s difficult to discover the proper route without trial and error. Dying and retrying becomes commonplace in later levels, with massive five story drops popping up everywhere.

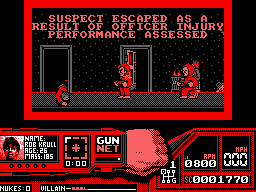

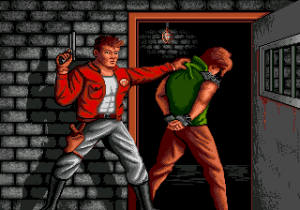

Melee-weapon toting DOA scum are everywhere and can be dispatched with two weapons: the Tonari Snare Gun and the .95 AutoMag. The former functions as a net and is required if the area’s boss needs to be captured alive. The AutoMag on the other hand explodes enemies into a twitching puddle of gore. Had the game been more popular, this probably would have sparked the same controversy as Mortal Kombat a couple years later. Instead, North American magazines largely ignored the title. The only real reactions that can be found pertain to the Amiga original from European print sources, which either praised or shunned the blood and guts. Commodore User gave the game a 77%, noting the detailed and gory graphics and little else. Meanwhile, Amiga Resource, The Games Machine, and Amiga User International gave the game low ratings, all expressing concerns regarding the violence. Many print sources also compared the violence to Death Wish 3, a similarly brutal C64 game also by Gremlin Graphics, in which a pixelated Charles Bronson blows up goons with a rocket launcher.

While blowing up punks isn’t the wildest idea in the realm of video games, much more unusual is how you can kill a variety of civilians who don’t directly harm the Techno Cop. Different people, including little boys, grannies, and runaway baby carriages fill the halls of the DOA tenements. While mostly harmless, running into an innocent causes Techno Cop to stub his toe, forcing him to uncontrollably start bouncing up and down on one foot and leaving the player open to a quick bludgeoning from the DOA. The easiest way to remedy this is to shoot the civilians, at the cost of only a few thousand points. There are few prior action games where players can gleefully mow through innocents with reckless abandon; in most rail shooters, the player will lose some health, while all the Grand Theft Auto games and their many clones send the police after you in a flash. Here, the terrorism has little impact on gameplay, making Techno Cop a gleefully cynical game.

Aside from being a precursor to our now violence- and blood-ridden gaming landscape, Techno Cop is an interesting footnote in a few other ways. It was the first success of main programmer Kevin Hoare, who went on to become the Studio President of Rockstar North, now overseeing big budget games that still alternate from driving around to shooting people on foot. The Genesis port is also noteworthy for being one of the first games to feature a parental warning, recommending adults only buy the game for children twelve and older.

While the game was not a huge success, it proved successful enough for RazorSoft and its controlled interest development team Punk Development to continue creating mature-themed games. Unfortunately, Sega eventually started to grow wary of RazorSoft’s approach. This eventually lead to a large federal lawsuit in which RazorSoft claimed Sega violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by refusing to license Stormlord, Punk Development’s latest game. Sega claimed that they had violated the licensing agreement, leading to said agreement’s termination. The results of this case were never divulged to the public, but the probable issue was that Stormlord originally featured nude fairies. In the end, RazorSoft had to manufacture Stormlord themselves, which must have been a large financial burden. A few more games were published, including the much gorier Death Duel, before RazorSoft and Punk Development quietly dissolved their partnership and totally disappeared in 1992, years before extreme violence became a normality in the industry. Many of the staff from Punk moved to Iguana Entertainment, where lead designer Jeff Spangenberg eventually became the studio’s president.

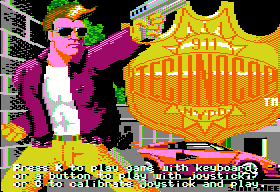

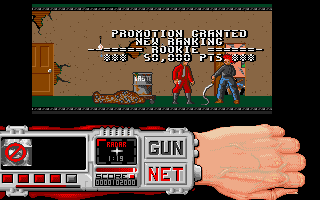

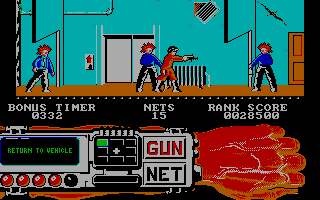

Most of the Gremlin Graphics computer versions of the game received little love from critics. The handful of positive reviews were all directed at the 16-bit Amiga original and the Atari ST port. These versions are clearly what the Genesis version was based on, although they both lack the amazing digitized voice sample featured in Punk Development’s version.

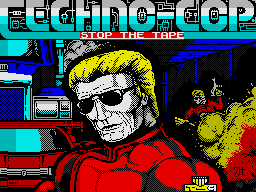

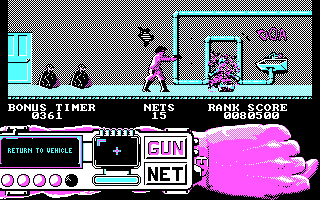

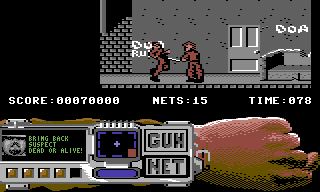

The other ports are largely inferior. The Apple II version is the only game ever produced by a mysterious unit called James & Paul Software. It loses all of the gore animations while maintaining the original’s look and feel. The DOS version awkwardly scrolls screen by screen, but otherwise plays and looks as good as the other 16-bit versions. The Spectrum and Amstrad versions are totally different, with cartoony characters that turn into clouds of smoke and an overall much slower pace, both in the driving and shooting sequences. The Commodore 64 version is probably the worst looking and playing version, with all sections playing slower and a tendency for the racing portions to suffer from graphical glitches.

Tengen had Probe Entertainment develop a port for the NES in 1992. Rumors say the game was completed but scrapped, probably due to the 8-bit console’s impending retirement. The only evidence of this port is a few sprite sheets and a complete soundtrack circulating online. A retailer price list in the January 1994 issue of EGM also advertised Techno Cop 2: The Final Mission at a price of $52. No other evidence of its existence is currently available, so there’s a high chance of it being just information or a complete vaporware title.

Screenshot Comparisons

Driving

Side-Scrolling