- Colonel’s Bequest, The

- Laura Bow in: The Dagger of Amon Ra

Envisioned by Roberta Williams, Laura Bow is the star of a short lived series that draws from classic mystery novels. Based on a healthy diet of Agatha Christie and games of Clue, the heroine finds herself in situations where her compatriots are all being murdered under mysterious circumstances. They rely heavily on mystery tropes, and thoroughly acknowledge this fact, giving them sort of a classic feel. Based on silent movie actress Clara Bow, at least in name and looks, Laura is meant to personify the spirit of the Roaring Twenties, much as the woman she was based on. In practice it doesn’t quite work out like this – she’s largely a silent protagonist in her first game, The Colonel’s Bequest, and morphed into a polite Southern belle in her second game, The Dagger of Amon Ra. Laura Bow is still unlike most other computer game heroines, not only for her personality but for the setting of her adventures. Despite being a cornerstone of American history, the 1920s have rarely been explored in gaming.

The lineage of the Laura Bow games can be traced way back to Sierra On-Line’s very first game, Mystery House. Sierra published several text adventures before introducing King’s Quest and changing the landscape of the genre forever. In the new age of graphic adventures, they occasionally found themselves revisiting and revising some of their older games. King’s Quest was loosely inspired by Wizard and the Princess, Sierra’s second game, while Leisure Suit Larry was explicitly a remake of Softporn Adventure. While taking a break from the King’s Quest games, Roberta Williams decided to once again develop a mystery game. While not technically based on Mystery House, it borrows elements from the same Agatha Christie stories, and reuses many of the same themes, although it’s obviously much more fleshed out due to the use of more advanced technology.

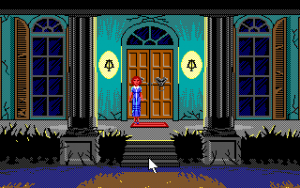

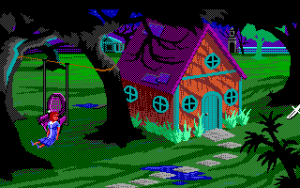

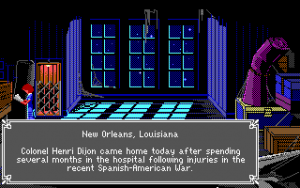

The heroine is Laura Bow, an old-fashioned Southern girl from Louisiana attending Tulane University in New Orleans. Her friend, Lillian Prune, invites her to spend a night at her family’s mansion. The gargantuan house, on an island in the middle of the swamp, is inhabited by the aging Colonel Dijon, who has called his kin for the reading of his will. This is clearly a bad situation, as the Dijon family has a number of quarrels, not to mention all of the drama going on with the Colonel’s flirtatious French maid. As to be expected, people start dying one by one, with Laura somehow being the only one noticing. She needs to survive the night, all the while exploring the old mansion in hopes of finding the true killer.

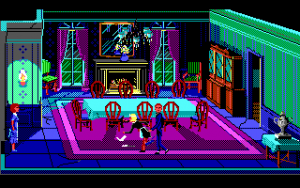

While not always the best game designer, Roberta Williams was always trying something new and unique with her games. Movies and books, by their very nature, are linear experiences which must involve the viewer/reader at all moments. Most games are developed the same way too, in that the world revolves directly around the player and their actions, but The Colonel’s Bequest tries to shake things up a bit. There are secret meetings, arguments, fist fights and murders, all going on in the house, but Laura isn’t necessarily privy to viewing most of them, unless she’s at the right place at the right time. It creates a sense that there’s a living world beyond the immediate gaze of the player, one which could theoretically go on even if the player wasn’t involved.

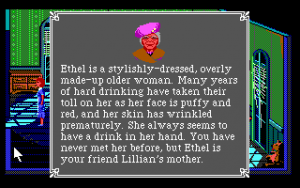

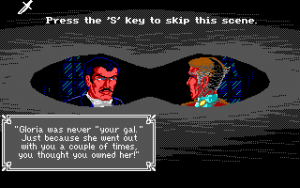

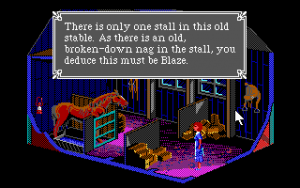

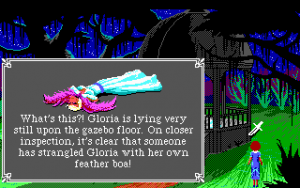

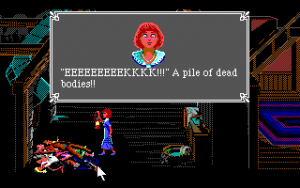

There are many problems with the whole package, the least of them being that the mystery just isn’t terribly interesting. The characters are all familiar archetypes, and most are named after figures from the era, like the suspicious doctor Wilbur C. Feels (W.C. Fields), the untrustworthy lawyer Clarence Sparrow (Clarence Darrow), and the stuck up actress Gloria Swansong (Gloria Swanson). The French maid is named Fifi, and the butler is named Jeeves, while Colonel Dijon is a not-so-subtle reference to Colonel Mustard from Clue. Despite their naming conventions, they are sparsely characterized, as they’re mostly defined by their vices or conflicts, and little else. Therefore, it’s hard to feel for the characters when they get killed. Laura has no real personality either, and it’s almost sociopathic the way she stumbles upon body after body, acts horrified for a moment, and then completely carries on for the rest of the night as if nothing happened. Laura can, of course, get herself killed, usually by walking into some place she shouldn’t. These events are easily avoidable once you know where they are, but there are a few sticking points, like the shaky railings on the second floor, where it’s entirely too easy to stupidly fall to your death, or the chandelier, which will randomly fall on you if you walk underneath it. (There’s also an amusing reference to Psycho if you decide to take a shower.)

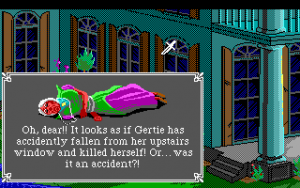

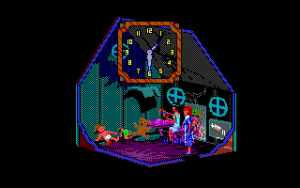

The most frustrating issue is the way time is structured. There are eight acts, one for each hour, and each hour is further broken down into fifteen-minute quarters. The clock does not operate in real time – instead, it advances when certain triggers are met, usually when walking in certain rooms or interacting with certain people. There’s rarely any indication of how to do any of this without stumbling around, which leads to another problem – it’s far too easy to propel forwards through the plot, missing important events without meaning to. You might find two people yelling at each other, and it will make absolutely no sense if you failed to view an establishing scene from earlier on. When you barge into two people chatting and they get pissed off, you were supposed to crawl into one of the many secret passages and spy on them rather than charging into the room, but how would you know that beforehand? There are only a few scenes that are required viewing, and they’re mostly so Laura can happen upon the dead bodies.

The strange time-skipping also causes some severely awkward aspects that totally defy logic. Walk into a room and find a person sitting happily. Exit the room and immediately re-enter, and you’ll find them dead. Yes, in that split second, someone else snuck in the room, murdered them, and left without so much as a sound. And then, once you leave the screen, the bodies will mysteriously disappear, so even if you can convince one of the other characters to check for the body, they’ll simply think you’re a lunatic. It’s not much of a spoiler to say that the killer isn’t a ghost – they’re bound by the rules of reality, and turning them into a phantom so it fits into the game’s narrative framework almost completely undermines the whole experience.

By its own admission, The Colonel’s Bequest really isn’t even a traditional adventure game. There are very few puzzles to solve, and most of those involve an optional treasure hunt that reveals a bit of background on the Dijon family. When you break down the components, all you do is explore and spy on the family members, which translates into wandering around and being very meticulous. The onus is put upon the player to question the other characters, discover their motives, and attempt to solve the mystery for themselves before the night is over.

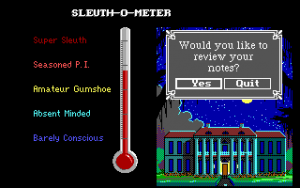

Uncovering this backstory is supposed to be the point of the game, but one can’t help that it feels superfluous by the end, where the gist of the story is spelled out for you anyway. Laura is put in the classic situation where she finds two people struggling, and needs to use what she’s learned from earlier on to decide who to shoot. Your decision leads to one of two endings, but it’s easy to figure out the solution just through the mandatory scenes, and one of the endings is clearly the “bad” one. Regardless of which finale you get, you’re graded on your performance with a “Sleuth-O-Meter”. Like other Sierra games of the time, you get points for accomplishing certain tasks, although here this is all kept hidden from the player until the very end. If you’ve spied on all the right people, asked the right questions, and investigated the right items, you’ll get a perfect score. If not, you’ll be given some clues on what you should be doing on your next playthrough. Williams must have expected that very few people would really follow the plot all the way through, so the Sleuth-O-Meter is a way to provide some extra replayability, instead of just making the game ridiculously tough like their other titles.

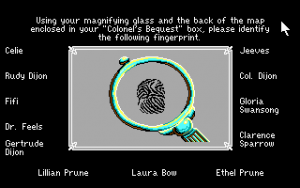

In spite of some of its awkwardly implemented elements, The Colonel’s Bequest completely nails the atmosphere. While it runs in the SCI0 engine and is limited by 16 color graphics, the artwork is consistently fantastic, easily outclassing any of Sierra’s similar games at the time. The mansion decor is a combination of purple and green, clashing against the darkness throughout the house, with the only illumination provided by the moonlight, pouring through the windows. The exterior, consisting of several gardens and courtyards, and surrounded by a bayou, is about as beautiful as you can possibly make a swamp with 16 colors or less. It’s one of the first Sierra games to use portraits to accompany dialogue, and includes several close-ups for important cinemas. All interaction is still handled through a text parser, though, which is a pain when interrogating the various characters about all of the other various characters. The story is presented like a stage play, complete with a cast introduction. The copy protection shows a finger print and asks you to identify it based on the included documentation. Get it right, and you’ll be asked to take a seat. Get it wrong, and you’re informed that the show is sold out.

Despite the narrative issues, the irritating deaths, and many, many illogical elements, it’s this classiness that helps The Colonel’s Bequest rise above mediocrity. And like most of Roberta Williams’ games, it’s a noble attempt at furthering what an adventure game can be, even though the programming restraints often show its limitations.