- Incredible Machine, The / The Even More Incredible Machine

- Sid & Al’s Incredible Toons

- Incredible Machine 2, The

- Incredible Machine, The (Mobile)

- Contraption Maker

A staple of any fine comedy — the incredibly complicated machine made of all kinds of wacky parts that somehow shouldn’t work at all, and yet is capable of performing some simple task in a convoluted fashion. This is what we know as the “Rube Goldberg machine”, so named after the cartoonist best known for his drawings involving simple tasks being performed by highly impractical machines. Such a concept makes for a great idea for a puzzle game, and the series is far from the first. Creative Contraptions, released in 1985, is a very similar idea, albeit in a very early form. It’s this series in particular that really popularized the concept, however, along with more than a few sequels along the way. While there have been plenty of imitators, few, if any, really quite match it for various reasons.

Despite getting several sequels, the main gameplay of the series never really drastically changes. New puzzles come by the dozens, a handful of new features are slotted in, and new parts become part of the myriad of machines. If you play one, however, you’re more or less ready to tackle all of them. It works out – when a series about solving puzzles makes a drastic change, you’re more likely to turn off fans rather than get new ones. (Just look at Lemmings, for example.) Because of this, it’s not really difficult to call any game but the latest the “best”, unless you particularly prefer the look of an earlier game.

Aside from a few questionable design decisions that’d be ironed out in future games, the original title makes just as fine of a start as any to dip into the series. It’s also highly likely to be the first many people grew up with, given that more than a few schools had copies of their own. Truth be told, it’s not really all that educational, given the sometimes strange physics and the general wackiness of the concept. Perhaps, at least, you could make the somewhat flimsy argument it teaches kids “creativity” and “problem solving skills”. That, and it holds up a lot longer than your average Super Solvers game.

There’s absolutely no plot to get in the way – there are puzzles to solve, 87, to be exact. Why? Well, that’s why you bought the game, isn’t it? Some of the puzzles have briefings giving the flimsiest of excuses on why you’re doing the things you do, but even that’s honestly more than what the game needs.

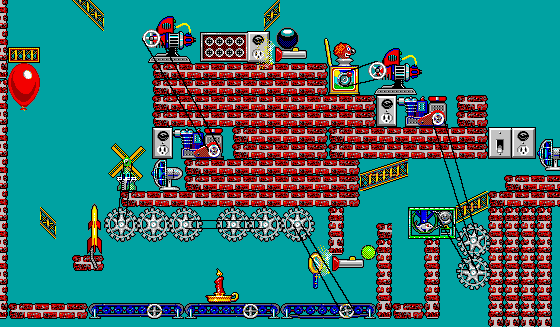

Each puzzle follows the same format – you’re presented with a field with various walls, objects, and other features placed across it. You’re presented with a simple task – usually involving making sure a certain thing goes in a certain place, activating one or more objects, or destroying certain objects. More specifically, you might be asked to pop every balloon on the field, make sure a mouse reaches a certain part of the field, or switch on a light bulb. To do this, you’re given a certain set of parts that can be placed onto the field as you like, provided they don’t overlap something already on the field. Certain parts can also be rotated, which you’ll have to do plenty of to solve most of the puzzles.

There’s a wide assortment of parts to place down, all of which have their own unique functions. Generally, they make logical sense – balloons float up, and get popped by sharp things, dynamite explodes if its fuse gets lit, basketballs roll down inclines and bounce up when they fall upon trampolines. Some objects also need to be paired with others to function – a flashlight won’t do anything if nothing hits its switch, which means it can’t have its light focused through a magnifying glass to light the fuse on that cannon. A lot of objects also need power to function, which can be provided in various ways – through switches, by wind power offered by windmills, solar power provided by light, and so on. You’ll also make use of a lot of rope and cable, which needs to be strung around the field in various ways to make sure certain objects get tugged or certain other objects like gears are given motion, respectively.

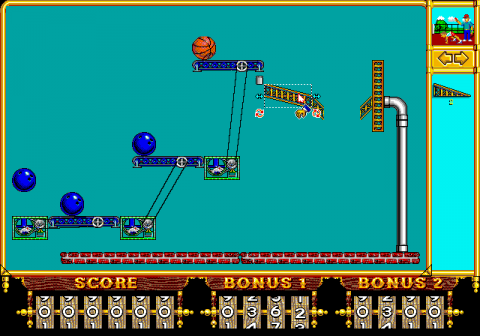

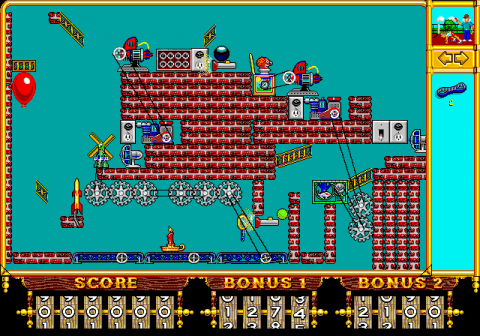

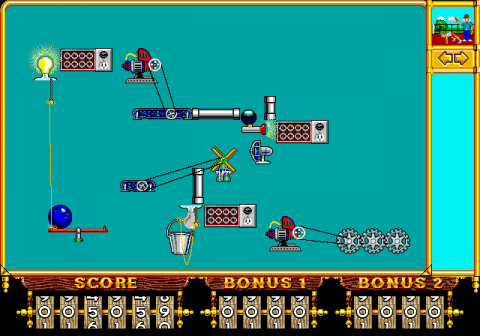

The first puzzle of many — they’re gonna get a lot meaner than this.

It’s not all mechanical bits and pieces you’re dealing with, however. Sometimes you might be tasked with handling live animals like cats and mice who have their own interactions to work with. They’ll generally stay still, but cats will chase mice, who will naturally flee, while shattering a populated fishbowl will draw a cat towards it. A monkey on a bicycle won’t do anything until the a sharp tug pulls up the curtain hiding a banana, which will motivate the monkey to pedal and power things attached by cable to the bike. None of the parts get especially wacky aside from those few, and they are, of course, part of any self-respecting Rube Goldberg machine.

While you’re placing objects, nothing will happen – things you place remain frozen until you click the “go” button, which activates your machine. If you’ve placed your parts correctly, you’ll accomplish the thing you were trying to do and move on to the next puzzle. If not, you’re thankfully not punished in any way – you’ll just have to stop the simulation, mess around with your parts, and give it as many tries as you need. It can be helpful to place down one part, run the machine to see what happens, and try filling in the holes as things inevitably go off track. The game’s forgiving nature makes it useful to experiment as you go along, just to see how trying one thing or another works. There’s also thankfully no timing involved – once you’ve started the machine, the only control you have over it is to stop it once you’ve seen enough.

One particular example is a puzzle where you’re asked to pop a balloon. It all starts when a tennis ball flicks a switch, turning on a fan that sets a tennis ball rolling onto the switch of a flashlight. The light of the flashlight is focused through a magnifying class onto the wick of a candle, which gets set aflame. Meanwhile, the tennis ball hits the cage of a mouse, who runs on a wheel that turns a set of gears that are attached to a generator that runs a motor. That motor is attached to a jack-in-the-box that launches a cannonball onto a flashlight that gives a solar panel enough power to motor attached to another generator. This second generator turns on a fan that blows a windmill, connected to several conveyor belts that now convey the now lit candle under the fuse of a rocket – which flies up and pops the balloon with its exhaust.

That’s, of course, assuming that you’ve placed everything in the exact right places.

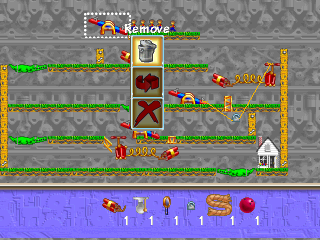

Not all the puzzles are quite that complicated, but it’s the sort of thing you can generally expect once you get past the tutorial stages. There’s a whole lot of trial and error involved, as there’s a whole lot of parts that can go a whole lot of places on that field. With all the interactions that can occur with the game’s parts and the game’s sometimes unknowable physics, most puzzles often have several solutions, with some being easier to implement with others. The game often helps with this by supplying you with parts you might not actually need, some of which may not even have use in the puzzle at all.

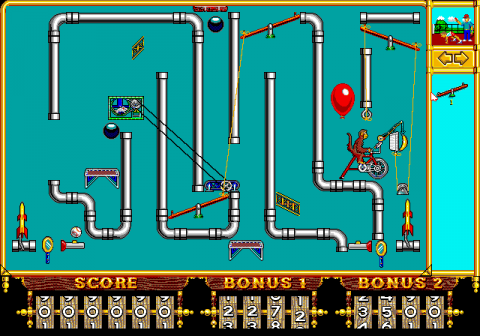

Here’s one way to solve a puzzle.

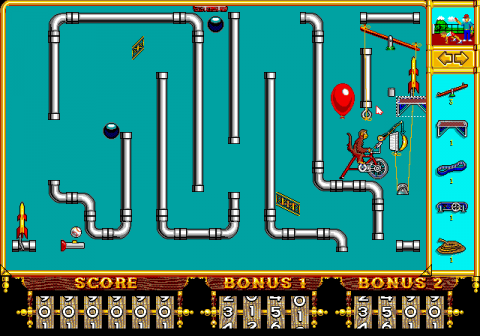

Then again, this works just as well.

It gets especially tricky where ropes and cables are involved. They’re a part of many puzzles, and figuring out just how to use them can be a little frustrating. Certain objects need to be tied with rope have to be tugged in just the right way to get them to work, which often involves stringing them around pullies to find just the right setup. Meanwhile, cable only stretches so far, which means you often have to be very exact with your gears and how they connect to things that need their motion to get them going. It’s frustrating, since rope and cable are often a part of many puzzles, and the way their physics work isn’t entirely clear.

In fairness, ropes and cables aren’t the only thing you’re going to have to figure out, and the game does a good job at keeping themselves varied. There might be times when you’ll have to figure out how to make certain things happen at the correct time. Sometimes, parts might need to be used in ways you might not have considered to get things done. There are even times when you have to prevent something from occuring entirely, like making sure a revolver’s bullet doesn’t hit whatever’s in front of it. While pretty much every goal can be summarized in a single sentence, the game still does a good job of keeping you guessing on just what you’ll do next.

By the game’s very nature, there’s going to be a lot of trial and error involved – starting the machine to see what happens, placing a new piece, then another, trying it again, moving things around, and so forth. Depending on the solution you’ve come up with, success and failure might hinge on pixel-perfect placement of your parts. You might run the simulation one way, see a failure, and then move an object just a couple of pixels another way, before suddenly seeing everything work perfectly. One particular flaw amplified by this is that there’s no way to fast forward the animation once it’s begun – and all those failed attempts can begin to add up.

The game also handles progression somewhat unusually – from the start, you can freely select from 47 of the game’s 87 puzzles. To unlock anything beyond that, however, you’ll have to finish the 47th puzzle, which will then unlock the 48th, and so on. Any puzzles before that point aren’t strictly necessary, but given how tough later levels can get, skipping ahead won’t make the game that much easier for you. While the game saves the highest level you’ve reached to memory, it also offers passwords that track your progression and optionally, your score. Given that score has no meaning in this game, however, they’re mostly better for bypassing the most difficult puzzles.

If you’ve exhausted yourself trying to figure out the puzzles, however, the game also offers a sandbox mode. Here, you’re given the opportunity to place an unlimited supply of every part in the game wherever you’d like, as well as adjust the gravity and air pressure of the simulation. It can be a good way to see how certain parts work together, which might give you an idea for some of the puzzle solution. More likely, however, you’ll probably place a ton of TNT and write silly words in with the wall parts. Either is valid, since you can’t actually make your own puzzles in this mode.

The graphics are somewhat on the simplistic side, but have enough style to them that they easily fit with the comics that inspired the game itself. There are no backgrounds aside from a light blue fill, which, while plain, never becomes distracting from the puzzle itself. The music, while all in MIDI format, features a wide variety of styles, from slow country-style music to metal, to a funky new jack swing-esque track. They’re all pretty listenable, and while there’s not that many songs, the fact that the game offers a different track for each puzzle keeps them from getting old too quickly.

Overall, the game makes for a great concept, but the execution will definitely depend on how patient you can be with it. It’s definitely a game that demands a lot of effort and time spent to really enjoy, perhaps more than some people might be willing to offer. The basic concept is solid, however, enough that it would remain nearly untouched with later games. There are a handful of minor design flaws that get ironed out with future sequels, but for the most part, you can expect a lot of the same with this first release. If you’re willing to put with the sometimes fiddly gameplay, you’ve got plenty more puzzles to solve.

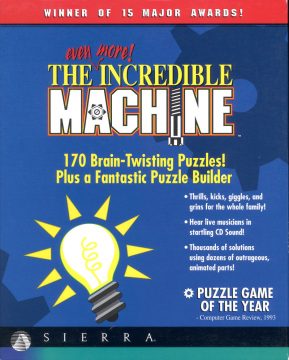

The Even More Incredible Machine – IBM PC, Apple Macintosh

Cover

More of an expansion pack than a true sequel, TEMIM offers the same gameplay, interface, and graphics as the original. All 87 puzzles from the first game are included, plus 73 more exclusive to this version. The password system has also been removed entirely, with all puzzles now unlocked for play from the very start of the game.

The new puzzles have a variety of new parts on offer, most of which lean towards the wackier end. There’s Mel Schlemming, a tiny man who much like his namesake, will continually wander forward no matter what dangers lie in his path. Sometimes you might be instructed to help him walk into his tiny house. Other times, you might be made to have an alligator eat him. On that somewhat dark note, the alligator can also bounce things off of its snout and tail. Mice will scamper towards cheese if they can see it, while pinball bumpers bounce things off of them and generally cause a whole lot of chaos.

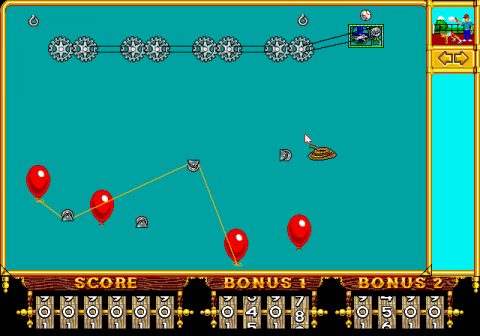

Something about this feels wrong in so many ways.

The audio has also seen some enhancements, with a few new tracks covering a few new styles, like a jazzy “big band” track and a noir-styled “detective” track. A CD version also exists alongside the disk release, with the former playing music straight off the CD. It sounds significantly better than it would if you had still been playing on a Sound Blaster, with a few tracks even adding vocals at appropriate points. In a small touch, the puzzle objectives are now spoken by a disembodied voice, presumably the professor the lab you’re so busy bouncing tiny men off of pinball bumpers in. This particular release is what you’ll find on digital distribution.

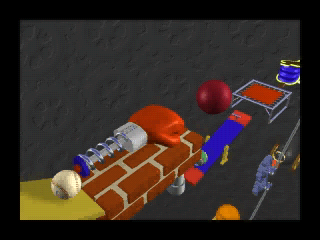

The Incredible Machine / Pala Rancho – Panasonic 3DO

The first of a very small number of console ports, this particular version is less its own unique entry and more a further enhanced version of Even More Incredible Machine. 28 new puzzles have been added to TEMIM’s set, most of which are on the extra difficult side. Aside from obviously using a controller, however, it’s basically the same game. On that note, the controls do feel sluggish at times – the cursor can be a little slow to accelerate, which can lead to a somewhat uncomfortable ‘sticky’ feeling. That said, the button layout is fairly logical, so the slow cursor is something that can be acclimated with, given time.

There’s also been a visual and audio overhaul, with everything having a brighter, shinier, somewhat cartoonier look than the computer versions. Unfortunately, the game lacks the resolution of the original version, to the point where some puzzles have to be scrolled around to see their entirety. Everything is also far more pixellated, which while it doesn’t get in the way of the game itself, certainly makes it pale in comparison to the other versions. On top of that, when the simulation is running, it does so with a far choppier framerate. This doesn’t really cause any problems besides make things take longer to finish, but it is somewhat of a bother once you’ve played for long enough. Overall, it’s not a terrible port, but unless you’re dying to play the exclusive puzzles or you’re a major fan of the system, it makes a better curiosity than anything.

There’s a pretty cute FMV intro to start things off, now.