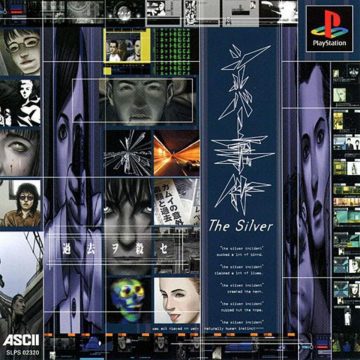

- Silver Case, The

- Silver Case, The: The 25th Ward

Prior to founding Grasshopper Manufacture, Goichi “Suda51” Suda got his start at Human Entertainment, where he created, among other things, the twisted “Syndrome” series, consisting of two titles: Moonlight Syndrome and Twilight Syndrome. Although he directed these games, he never felt that he had complete creative freedom. As said in this interview, Suda51 was inspired by actual crimes in Japan to tell gritty crime dramas based on around real life, but he was restricted by Human Entertainment while making Moonlight Syndrome, so he wasn’t able to make the game as violent or true-to-life as he would have liked. This was how Grasshopper Manufacture came about: so Suda would have the complete creative freedom that Human didn’t allow. And Grasshooper’s first game was The Silver Case.

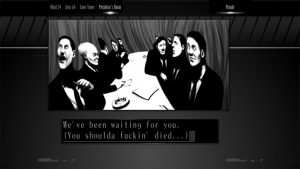

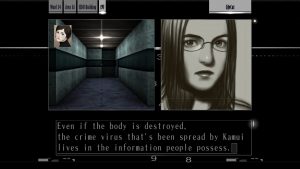

The primary story of The Silver Case, Transmitter, follows a survivor from a government task force called The Republic (named by the player, though his canon name is “Akira”), who eventually joins the police force known as the Heinous Crimes Division. The game’s events transpire in a fictional district within Tokyo known as the “24 Wards”, which is the result of the city being divided between different governing parties. While certain criminal cases call for the government and police to collaborate, as in the game’s primary scenario revolving around a legendary serial killer known as Kamui Uehara, the introduction states that the two groups each serve different interests, and even political factions, namely the CCO (which is run by a civic branch of government) and the TRO (run by a technological branch of government). Though the story starts out with the primary focus on the police attempting to track and apprehend Kamui Uehara, though the conflict blossoms out from being about a mere individual to affecting entire corporate organizations, political factions, and even inspiring copycat killers.

The events of each case rarely make sense during an initial playthrough. The protagonist doesn’t comment on major events as they happen (if he’s even there to witness them), they’re often told as if everyone involved is already expected to know the significance. For instance, a group of hackers are the focus of Case 4, and much of the case is spent in a chat room navigating their confusing interactions. After they succeed in causing a city-wide power failure, they disappear from the story and are never seen again. This could be considered part of the theme in Case 5, as their actions help bring about society’s fascination with Kamui Uehara and the serial killings, though it’s never explicitly spelled out; the meaning is largely left up to player interpretation.

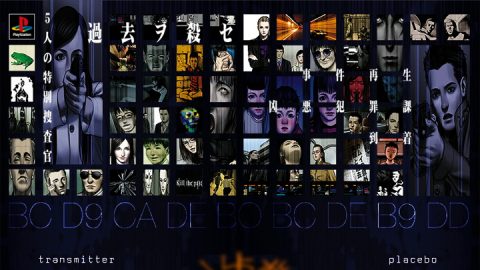

If the core story of the game proves baffling due to the obtuse nature of the storytelling, Suda actually did something to help it become more understandable. He brought on a co-writer, a novelist named Masahi Ooka. While the Transmitter story focuses on the protagonist’s silent observations of crime scenes and the detectives’ interactions, there is also a secondary story: Placebo, each chapter of which is unlocked after clearing the Transmitter chapter that precedes it.

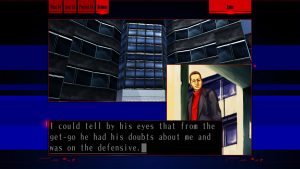

The protagonist of Placebo is also anything but silent. The player takes on the role of a reporter named Tokio Morishima who’s investigating the events surrounding the reappearance of Kamui Uehara, and has his own take on events. While he manages to break down the more confusing elements of the story, he has his own problems that pose many mysteries of their own. Placebo is also a very straightforward story, more of a literal visual novel than the Transmitter story.

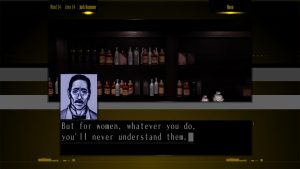

While Akira’s adventure involves investigating crime scenes and moving around different locations, Tokio mostly stays in his apartment: reading emails, talking with his turtle, and sleeping. When he does venture out, it’s to talk with contacts, get drunk at the local bar, or purchase his favorite cigarettes (brand name “Placebo”) from a nearby vendor. The difference in storytelling between Suda and Ooka is very clear, as Ooka is more straight-forward versus Suda’s obtuse and open-ended narrative, but both still spin an engaging tale. In this interview, Ooka talks about how the Placebo scenario was written to be the “other side of the coin” for the Suda scenario, meant to offer an alternate perspective from a journalist’s point of view, instead of an investigator actually in the thick of events.

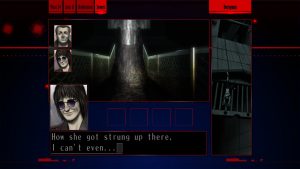

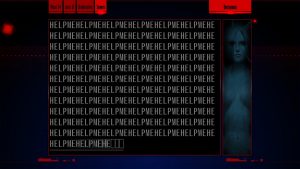

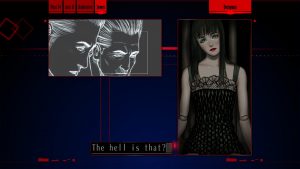

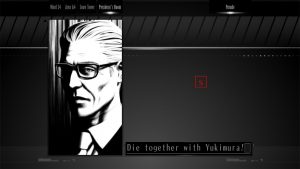

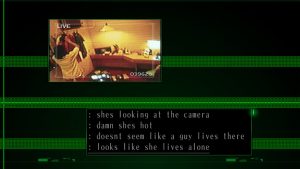

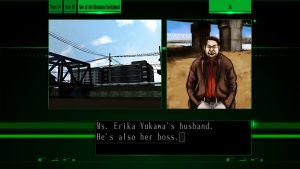

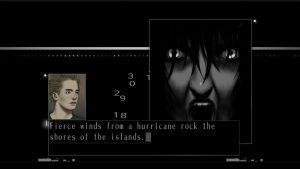

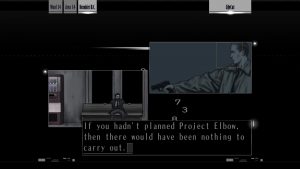

Grasshopper started out with a team of only five people, so this required the group to think of a way to tell a story using limited means. Since The Silver Case had such a small team, Suda51 devised a simple solution to minimize the need for elaborate presentation: The Film Window system. Rather than take up the entire screen, most of the visuals consist of a backdrop of thematic imagery for each chapter. The fourth case (titled Kamuidrome) has a dot matrix-esque array of text and green colors running through the background. Others, like Parade, has various interlocked words, and Lifecut shows a constant rotation of numbers circling around each other.

What displays with each event in the story also depends on what’s taking place. While the majority of The Silver Case uses a visual novel-style presentation, with text and traditional static artwork, some chapters incorporate animation, 3D cinematics, and even live action footage, which is used to optimum effect during a segment of the game in which the player is watching secretly recorded footage of an idol from a hidden camera in her room.

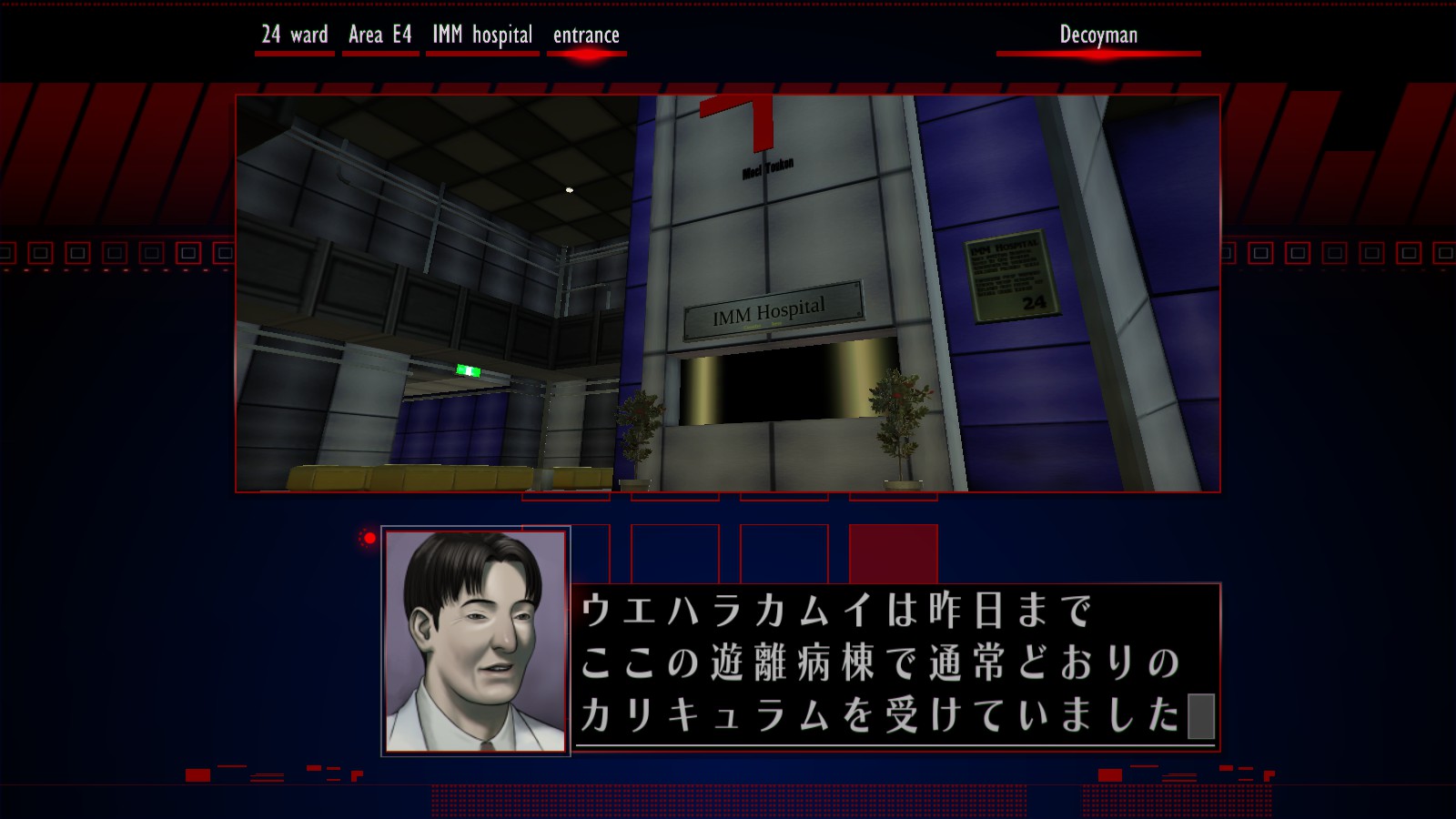

While much of the game’s story and presentation are done through visual novel progression and Film Window vignettes, there is also investigative segments of gameplay that break up the story-driven walls of text(of which there are many). Though these are typically brief and involve less puzzle solving and more investigative leg work, they’re most comparable to Tex Murphy’s first person investigations, though the Tex games’ adventure segments were far more thorough, non-linear, and involved way more puzzles. They also limit the player to four directions, as opposed to the free range exploration of the Tex Murphy games.

The Silver Case typically has one major puzzle per chapter, and they typically involve knowing who or where to go and then entering the appropriate piece of data into a terminal. Some puzzles were so difficult that it lead to Suda making its predecessor, Flower, Sun, and Rain, having far simpler puzzles that were strictly based around numeric solutions.

While the connections to Moonlight Syndrome and the sequels (Flower, Sun, and Rain and Killer7) may appear vague if even discernible, the’re definitely there for the observant viewer. The prologue chapter of Transmitter, Lunatics, focuses on the few remaining survivors from Moonlight Syndrome, shortly before they are killed by the police force and Republic.

Flower, Sun, and Rain appears to be a completely separate story, though as the tale of Sumio Mondo and an endless day spent at a resort hotel drags on, it becomes clear there aren’t just connections to The Silver Case, but even several returning members from the original cast, including some characters who are referenced but never seen. Sundance Shot, for instance, was seen in the opening of The Silver Case, but never actually appeared in-game. The main character himself is eventually revealed to be Sumio Kodai, a key figure in The Silver Case, who was later imprisoned for crimes committed against a corrupt corporation. However, even though they’re technically the same characters, according to Suda 51, the storylines are not directly related, much in the way that Meryl Silverburgh appeared in both Policenauts and Metal Gear Solid despite not being canonically back of the same universe. Whether or not Flower, Sun, and Rain is actually happening, or a giant construct of his psyche, is left wide open to interpretation.

Killer7 largely has its own story, though themes of political conflict and conflicting ideologies are as present as ever. Most of the connections to the earlier games are thematic in nature, namely the underlying theme of “Kill The Past”, which is why the three games are known as the “Kill The Past” trilogy. Each of the characters, in some way, are haunted by events in their past, and must eventually accept then and move on before they can develop, or in some cases, accept an inevitable end.

This is also a theme of No More Heroes, the last game Suda51 personally directed, though its events are far more satirical in nature. Travis Touchdown certainly has a deranged past, though he doesn’t confront it until the very end. Most of his time is spent living it up and gathering money to impress a woman and kill every adversary in his way to become the greatest killer in Santa Destroy. The ending also implies that the entire game could have been simply the result of the hyperactive imagination of a little girl.

Another connecting factor between each of Suda’s Kill The Past titles is the music. Each has maintained the same composer: Masafumi Takada, who has since left Grasshopper to work on many other games, namely the Danganronpa series. Each of his works has a different style that reflects the world the music accompanies. While Flower, Sun, and Rain has a tropical and relaxing motif, and Killer7‘s score runs the gamut from jazz to techno to classical, The Silver Case relies primarily on ambient, moody synths. Takada typically makes use of a different track for each scene, and occasionally for key characters, such as Tokio Morishima’s catchy theme that always plays in his apartment, and the down tempo jazz track “Jack Hammer”, for the bar he often frequents.

Another connecting factor between each of Suda’s Kill The Past titles is the music. Each has maintained the same composer: Masafumi Takada, who has since left Grasshopper to work on many other games, namely the Danganronpa series. Each of his works has a different style that reflects the world the music accompanies. While Flower, Sun, and Rain has a tropical and relaxing motif, and Killer7‘s score runs the gamut from jazz to techno to classical, The Silver Case relies primarily on ambient, moody synths. Takada typically makes use of a different track for each scene, and occasionally for key characters, such as Tokio Morishima’s catchy theme that always plays in his apartment, and the down tempo jazz track “Jack Hammer”, for the bar he often frequents.

The Silver Case was originally an unlocalized PS1 title, and long seemed doomed to remain that way, since even attempts at a DS version fell through. This changed when, after a long period of time in which Suda was trying to find an appropriate partner, Playism and Active Games Media became involved. As stated in this interview, Suda was long reluctant to bring the game to the US due to the massive amount of text and work that would be required, but the team managed to convince him that they were up to the task of delivering not just an accurate but an era-specific localization, reflecting the year in which the game was developed and its events occur. While the game’s translation is very liberal and contains a significant amount of profanity, it bears noting that Suda51 considers The Silver Case a very important game in Grasshopper’s history, and was closely involved with the localization process.

Not only did the game receive a complete and accurate translation, which was already a massive undertaking in and of itself, Playism and Grasshopper also collaborated to completely redesign the game’s visuals, including redrawing many of the illustrations. While they retain the core aesthetics and appearance, and all the cinematics are unchanged with the exception of being upscaled, the 3D investigative scenes have been given a welcome face lift, as well as including improvements to speed up the gameplay, namely a faster means of exploration, and puzzles that can have the solution automatically provided if the player desires. Masafumi Takada’s score also remained completely intact, with the option of a remixed OST done by current Grasshopper composer Akira Yamaoka, though the remixes are so faithful and near identical that it seems almost unnecessary to have the new OST. A PlayStation 4 port, released in 2017, adds two additional chapters, which are added as DLC to the PC version.

Although the reception of such an experimental and occasionally baffling game has been mixed, Suda51 fans have definitely been rewarded for their patience, especially since plans are possibly underway to localize the mobile-only sequel, “Ward 25”.

Screenshot Comparisons