- Suffering, The

- Suffering, The: Ties That Bind

Back in 2002, designer Richard Rouse III pitched the idea for a new game that would take the action of Devil May Cry, the atmosphere of Resident Evil, and the immersive world design of Half-Life, telling the story of a single character as they discover who they truly are deep down. With the additional inspiration of horror films like The Shining, Surreal Software ended up making an action heavy horror game with Midway Games, one that could be see as Silent Hill with all melancholy and despair replaced with rage, violence, and uncomfortably reality in its subject matter. The Suffering has a strange role in the history of horror games, because it takes from dozens of sources to create something that doesn’t really fit with everything that came before it. It has the pulp and kitsch of the cheesiest of Resident Evil rip-offs, but it manages to create an absorbing atmosphere by embracing and exploring subject matter few horror games have ever touched, or at least touched so effectively.

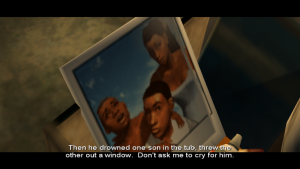

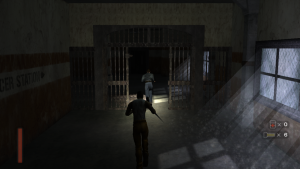

The game has you playing as silent protagonist Torque, a man on death row for the murder of his wife and children. Just as soon as he’s put in his new cell on Carnate island’s infamously horrible prison, everything goes straight to hell. Literally. An earthquake shakes the compound as guards and prisoners alike start getting slaughtered by grotesque mockeries of the human form armed with blades in their arms, guns on disgusting back growths, needles in the back, and other nasty things. Torque now finds himself in the position to escape, but he finds himself haunted by three ghosts of Carnate who have taken an interest in him. A man killed in the electric chair warns him, an executioner wants to see him kill, and a doctor who appears through old film reels wants to fix him. Its clear Torque isn’t all together, as he finds himself assaulted with strange visions, the ghosts of his dead family talking to him, and then there’s those times where Torque actually turns into one of the monsters trying to end him…

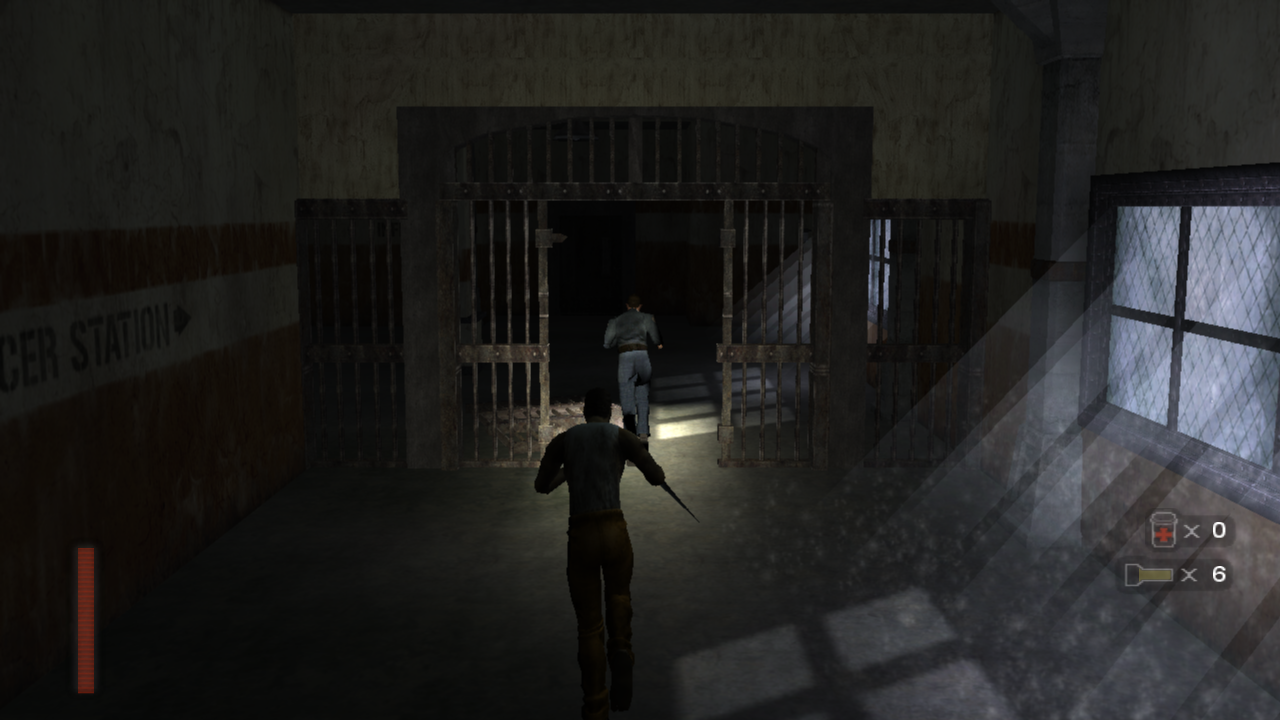

The Suffering is kind of fascinating, because it feels like something both ahead of the curve and very much of its time. The “of its time” part comes from the mechanical side. It’s a third person shooter that also lets you play the entire game in first person view, which was somewhat of a trend among shooters in the early and mid 2000s. Combat is fairly simple and focuses on either wildly swinging a basic melee weapon or shooting with a set of firearms you slowly gather as you move through the game, with the occasional puzzle segment here and there. Those segments can be pretty interesting, like one where you have to stop malfactors (the monsters of the game) from spawning by strategically pointing spotlights around (strong light does not agree with them, like the taken in Alan Wake), but its definitely an after thought. Everything comes back to action, and its pretty solid for this era and genre.

Third person shooters were still figuring out how to do 3D right, and Resident Evil 4 didn’t get things in order until 2005. The Suffering had to use design norms of the era with its two year development time so the team could properly focus on narrative and atmosphere, so there’s a good deal of jank. Because the game tried doing a “living world” sort of thing, where everyone and everything moved at its own time or when triggered, dialog and scene events would often overlap. In the worst cases, some characters would get trapped behind doors, which affected what morality points you could get, like Dallas getting stuck behind a door in the Hargrave fight so you can’t help him get out. Combat fared far better, though things got awkward in third person view when enemies got close, or when you’ve activated your insanity mode.

Torque can turn into a twisted version of himself when his insanity meter is full, which fights by ripping enemies apart with its claws. Its powerful, but controlling it with third person mechanics feels a bit strange if you’re more used to modern action games. You have to line up your sights with your target like you would with a fire arm, instead of an auto-aim situation occurring. Its not a huge issue, but its easy to see why this aspect was phased out in later third person shooters. Other small gripes include the moments where the game phones it in and has you fight a bunch of enemies in a small space before you can continue (usually with a turret hidden by the games heavy shadowing), the awkward difference between your weak basic jump and the strong jump you can use to grab ledges, and sections that require you explore an era with lacking variety in rooms and areas. The action is all serviceable, and certainly challenging on any difficulty besides easy, but what makes the game memorable is its particular brand of horror.

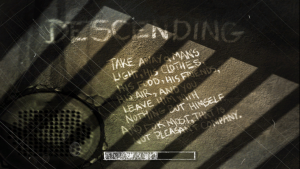

Where Resident Evil takes from zombie and B-flicks, and Silent Hill focuses on the psychological horror of the self, The Suffering takes both inspirations and adds in exploration of real world atrocities. It’s just as much about Torque as it is about the inhumanity we’re all capable of in large numbers, less about the evils a single person can do and what a culture can inspire and normalize. The sequel really pushes these themes, but the first game does a great job by focusing on the prison theme. From the dehumanizing views that propagate from just living in a prison to the use of atrocities in medicine and the carrying out of real world genocides (particularly with Haight, a ghost executor who killed others and later died in a gas chamber), the horror of the game seeps into every scene and room.

The malfactors are the evils done on Carnate made flesh and blood, each with a design that reflects various methods of murder and suicide, including hangings, beheadings, and being buried alive. You can thank their awful looks on Stan Winston, special effects legend who worked on The Thing, Terminator, and Predator. Where Silent Hill benefits from abstraction, The Suffering‘s monsters stick out for how obvious the symbolism is by making it as grotesque as possible. It works, re-contextualizing the violence on display into yet more horror poisoning the island.

Torque’s central story doesn’t fair as well, but its an interesting example of early use of morality systems outside RPGs or choice heavy genres. The gist is that there are moments in the game where you have to make a choice of some sort, usually signified by two voices in your head giving conflicting advice of “help someone” or “murder.” Because video games. You get evil karma for killing innocents, good for successfully helping people, and none if you fail to protect someone. This changes the ending, affecting just what Torque is actually guilty of, if anything at all. The neutral ending is the strongest, fitting the game’s themes much better than the other two, but the good ending also hints at bigger developments that get explored in the sequel.

The attempts to make Torque a blank slate you can latch onto, even making it unclear what his race or ethnicity is (something the next game fixes by making it clear he is black, possibly mixed), were a bit misguided and just result in a bland lead character we only get glimpses of depth of. The real stars are the people and spirits of Carnate, who see Torque not as he is but as a particular sort of person or an extension of themselves. Its only here that Torque’s generic design works, as it better lets you connect with the cast and define who your Torque is by your actions with them. Its by no means at the level of Mass Effect or Alpha Protocol, but the attempt, especially in the early to mid 2000s, is appreciated.

The Suffering doesn’t create a sense of dread or fear like you’d normally expect from a horror game, but it is absolutely a brilliant work of horror. It is researched well and creates a world that feels real in all the wrong ways, its more camp elements (like Dr. Killjoy, the Vincent Price-like mad brain doctor) used to subvert expectation and create impressive showpieces. Its a very clunky game, but there’s so much to explore and take in. It may be a flawed work, but its an incredibly entertaining and at times sobering one. This makes the sequel all the more interesting, because the team suddenly found themselves having to follow one of the greatest action horror games ever made on a heavily rushed development cycle. The results are somehow better than you’d expect.