In the mid-90s, the real-time strategy train had accelerated to full speed. Classic series like Command & Conquer and WarCraft had been established, with others such as Age of Empires and Total Annihilation to follow soon. Understandably, others wanted a piece of the real-time cake, among them MicroProse. Until then, MicroProse’s publishing ventures into the world of strategy had largely been confined to turn-based strategy titles such as Master of Magic and UFO: Enemy Unknown.

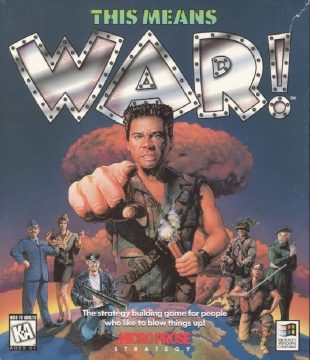

Tasked with the development of said strategy title, This Means War!, were StarJammer Studios. This Means War! is StarJammer Studios’ only game ever, implying that the studio was established specifically for this title. That said, most of StarJammer Studios’ staff worked on other games before and after This Means War!. Furthermore, the help of Illusion Machines was enlisted, though the extent of their contribution is unknown.

This Means War! has a fairly interesting premise. Everything starts with a fictional video game called Snark Hunter, which gain worldwide popularity. Created by a mysterious programmer named Shadowhawk, Snark Hunter turns out to be loaded with malware and soon destroys virtually every computer in the world. The result is a global collapse of infrastructure and public order. After a while, the dust settles and new leaders reestablish order. Here is where This Means War! goes off the rails. Almost every character is a wacky, wacky cartoon.

The player takes the role of Hotshot, a young and promising commander of the Free World Alliance. Hotshot is free of any sort of personality and pretty much just a stand-in for the player.

Cassandra Clarke is the Hotshot’s aide-de-camp and the intelligence officer of the Free World Alliance. She briefs Hotshot before every mission and comments on the development of the global situation. Will she take off her glasses and let her hair down over the course of the game? Indeed she will.

General Forrest Walker Adams is the Free World Alliance’s leader. He takes the role of a father figure for Hotshot and as such is killed halfway through the game – which would be sad, provided This Means War! gave us a reason to care.

Major McCormick is another commander of the Free World Alliance. Having ‘betrayal’ written on his forehead, cigar-smoking, sunglass-wearing McCormick does indeed betray the Free World Alliance at one point, styling himself Major Victory.

Crocodile Gandhi is an Australian Warlord and leader of the Church of Universal Siblinghood. Untrue to his name but somewhat in tune with the zeitgeist, he believes in power crystals and alien visitors.

Sheik Omar, an overweight oil sheik, is the leader of the Islamic world. Omar likes to talk about jihad and being the chosen one a lot, a portrayal that has aged poorly, and was never particularly clever to begin with.

Countess Nasty is a member of the House of Romanov, and a mix between spoiled Russian aristocrat in exile and Cold War era seductive spy. Her voice swings between seductive and bored, sometimes hitting both.

Napolienne, the only non-white member of the cast, believes herself to be the reincarnation of Napoléon Bonaparte. She has little to offer other than an ego even bigger than that of most of the other leaders as well as countless Waterloo references.

Mondo Khan comes equipped with fur, a katana, wears a taijitu arm band, and also talks about honor a lot – because why have one Asian stereotype when you can have all of them? To round things up, he is played by another white actor.

Shadowhawk is the creator of Snark Hunter and the game’s ultimate opponent. In accordance with this, his faction color is black, his voice extremely deep, and his secret military headquarters is in Antarctica.

While this sounds great, none of these characters is particularly amusing. Their lines get old quickly and are often recycled. Reduced to a sentence at the end of every battle, all of them fail to become anything more than a one-line joke that is repeated too often and was never all that funny in the first place. This Means War! does not even treat its player with full-motion video cheese and uses still images instead.

Unfortunately, This Means War!’s gameplay is as lackluster as its story and characters. The game was designed for Windows 3.x and accordingly, everything is either buried in menus or inconsistent. The trouble begins right away with the first tutorial-like mission. Here, Hotshot has to liberate Central America from Crocodile Gandhi’s forces. Superficially, This Means War! is not too different from other contemporary real-time strategy games: resources need to be harvested from mines, structures to be built by worker units, troops trained in production facilities, and power plants to be constructed to power everything.

In order to support all of that, houses are needed, and houses have to be supported by farms. Houses are built by dragging and dropping them from the headquarters to and empty building spot – and are the only structure to be raises this way. Everything else is built by worker units. Once a worker unit has been selected, selecting the build menu and then the build submenu is next. Why a submenu? Nobody knows. There is nothing else to select. There should not even be a submenu; all structures should directly be available.

Theoretically, the player can also select the build speed. Raising structures faster costs more money, but the slower build options are so agonizingly slow that they can be safely ignored. Credit where credit is due: when units are trained, they can be trained as single units, groups, or in an unlimited number. This is actually a good addition that was not a standard option when This Means War! was released.

Poor controls are by no means limited to the construction menu. Moving groups of units requires all of them to be selected. Afterwards, the player needs to hover over a single unit within the groups, hold down the mouse button, and drag and drop all troops to the location where they are supposed to go. One missed click and chaos ensues, especially when multiple groups of units are present in one location. Drag and drop is of course a Windows 3.x core feature, but there was no reason it use it here. It adds an extra step where none was needed, which would be less aggravating if moving troops was not one the game’s most commonly used commands.

However, the factor that renders This Means War! borderline unplayable are its speed and economy. Everything in This Means War! needs to be paid for. Money is gained via minerals, which in turn are gathered from mines. Mines have to be built over specific spots, lest they yield no resources. Once a mine has been constructed, lorries haul the resources from the mine to a refinery. A maximum of four lorries can service a mine at any given time, unless mine a refinery are very far apart. Roads will speed up the whole process, and can be created by letting the lorries dump their minerals onto a tile.

Building roads is advised in general, especially if the mine stands on rough terrain. Driving over rough terrain damages light vehicles, slows them down even more, and will eventually destroy them. Thus, getting any sort of steady income requires the player to set up the mine and refinery, a factory for the lorries, roads from everywhere to everywhere, houses to support everything, power plants to support the houses, and units to protect the very fragile lorries. And even after all of this has been done, money will not roll in fast. Generally, every faction only has access to a single mining spot. Some campaign maps will have additional random spots, but these can be anywhere from right in the player’s base to the middle of nowhere.

Speeding up the game is no fix for the slow and fiddly economy of This Means War!, which fits a city builder more than a military strategy game. When it was released, reviewers and consumers alike criticized This Means War! for its slow speed, especially those who played it on then older hardware. The game does offer multiple speeds, all of which are various degrees of ‘excruciatingly slow’. The exception is the highest speed, which accelerates the action to near-light speed and render This Means War! fully uncontrollable.

This Means War!’s trip-feeding economy singlehandedly breaks both single- and multiplayer. Almost all missions of the have same goal: destroy the enemy headquarters. Thankfully, most of them start the player with more money than they would ever earn from mines. The key to victory is to immediately spend all that money on the most powerful unit currently available. Once all credits have been spent, all units rush the enemy headquarters and destroy it.

This method works in almost every single mission and reduces their length to a minute or two. The alternative is a slow grind. There is no middle ground and multiplayer matches fare no better. The slow economy, painful to build up but interrupted with ease, encourages everyone to quickly spend their money on low-end cannon fodder and rush their opponent. There is no time for or point in going for high-end military hardware.

Even without boring but highly effect rush tactics, the This Means War! campaign offers no variety. There is only a single faction, and all of its units and buildings are dull and generic. The developers committed a cardinal real-time strategy sin: having a roster of units that largely replaces itself. Troopers are made obsolete by scout bikes, the bikes are replaced by halftracks, light tanks replace halftracks, followed by medium and finally heavy tanks. Even the game seems to know that simply removes the low-end units from the build menu at one point. Structures suffer the same fate, with windmills being replaced by solar panels and robotized farms replacing traditional farms. Ironically, the good old lorry gets no replacement with, say, a higher speed or a greater capacity.

There are a couple of exceptions to this rule. Hovercraft and helicopters, which can transverse both water and land, have some application, and so do long-range rockets launchers and planes. The latter is especially effective and destroys a headquarters in two shots. This may sound like a game-breaking feature on top of multiple layers of other game-breaking features, but This Means War! elegantly solves this problem by making planes only available in a few selected missions. Not that anyone would want to use planes all the time anyway; controlling planes in This Means War! is a nightmare. Aerial units cannot even be grouped.

What little variety This Means War! has is thus more or less forced on the player by removing certain units from time to time or making technology available very late into the campaign. At one point, the player suddenly gets access to the missile silo, which can either launch a devastating nuclear warhead or a satellite that reveals the entire maps – and interesting feature that barely gets used. Even more obscure is the research center, which only pops up during the last fifth of the campaign. Research can incrementally improve all kinds of units, but is so expensive that it has virtually no application.

Beyond repetition, the campaign has little to offer. Most of the maps are small and consist of nothing more than open terrain with the player and enemy bases at opposite ends. With the total number of missions being an impressive 40, staleness sets in quickly. The graphics looks fairy generic too, and tile sets and units lack any sort of personality. Equally repetitive is the music and especially the sound effects, whose quality is abysmal for a game that comes on a CD. Additionally, they clash with This Means War!’s premise of a post-apocalyptic world. Most areas look fine, and the apparent shortage of computers does not seem to affect anyone, even if a briefing or two hint at it.

The story is too thin the save campaign. In the end, it turns out that Shadowhawk, mastermind behind the apocalypse, is actually an annoying teenage brat named Sheldon. The delusional Sheldon apparently believes that everything is just a game and is unaware that his actions have killed millions. This Means War! does not comment on this either, a lame joke about violence in video games aside.

Occasionally, the games goes from campy to simply tone-deaf, with Clarke being amused by Poland being kicked around by more powerful actors, or the mission to conquer Japan not only being named ‘Thin Man‘, but also handing the player nuclear weapons to drop on the locals. The player’s faction, the Free World Alliance, on the other hand, is presented as morally superior to everyone else. An explanation for this is given – all other leaders are tyrants – but it clashes with rest of the game by putting comments on child labor and brainwashing on a flat joke sandwich.

This Means War! is a disaster of a game, and its core issues is its complexity. Complexity is a currency with which to buy depth, and This Means War! fails to do so. Worse, under its initial layer complexity, This Means War! is shallow and falls behind earlier strategy titles. It never got a sequel or expansion, and remains StarJammer Studios’ sole game. After this venture, MicroProse would stick with turn-based strategy, releasing only one more real-time strategy title with 7th Legion.

If you’d like to listen to a Patreon exclusive Top47kgames Podcast for This Means War! and a whole bunch of other great extra perks consider subscribing to the Hardcore Gaming 101 Patreon here!