The games industry has changed quite a bit in the past thirty years. While today’s biggest blockbusters are the work of hundreds of people toiling away countless man hours, the pioneers of PC and video gaming worked in a very different landscape. In the early eighties, a PC game created by one or two people could be quite profitable. Apple II games like Wizardry, Ultima, and Mystery House, each with a two-person development team, sold tens of thousands of copies. This meant six figure profits, and in a world where a small fraction of people owned a personal computer, this was a big success. More impressive still, console titles developed by single men such as Pitfall! and Kaboom! sold millions of copies, an achievement that would be impossible to replicate as technology advanced over the following years.

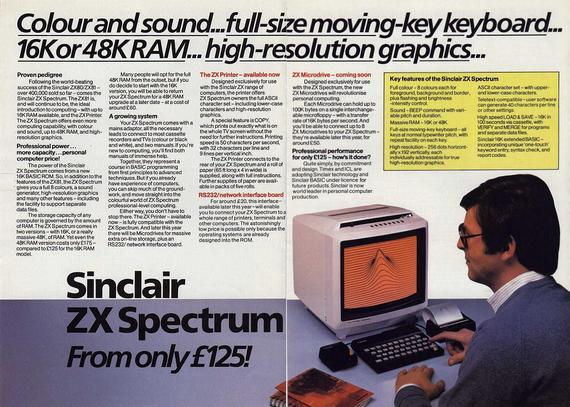

For the UK, the PC market greatly expanded with the introduction of Sinclair’s ZX Spectrum in 1982. With 16K or 48K RAM and capable of producing 15 different colors, the system was pretty low tech upon release. The Commodore 64, released a mere six months later, had more RAM, more ROM capabilities, and a much larger color palette. Still, Sinclair managed to gain a large market share thanks to its comparatively low price of £125. The Spectrum quickly became the king of cheap British home computers, finding its way into millions of homes.

A Spectrum advertisement circa 1982.

Seemingly overnight, a host of companies started churning out software and hardware for the inexpensive computer. For many aspiring game makers, Spectrum development was their golden ticket into the mainstream. Before founding Rare, Chris and Tim Stamper’s first company, Ultimate Play the Game, made over one million pounds off the Spectrum port of their first release, Jetpac. Other veterans like Earthworm Jim creator David Perry and PC strategy pioneer Julian Gollop started their development careers on the humble Spectrum. This environment was the backdrop for Gargoyle Games, a small independent software company formed by two systems analysts and a menswear specialist.

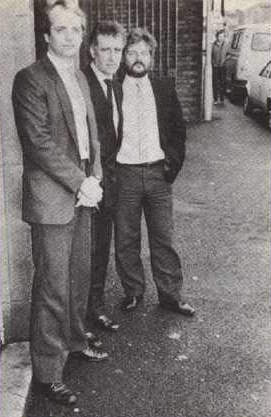

The men behind Gargoyle Games: Greg Follis, Ted Heathcote, and Roy Carter.

Greg Follis and Roy Carter became good friends working at a company called Hewitts. For fifteen years, they dealt with different mainframes and served a variety of different roles. The pair eventually had their own office, reportedly because of their loud, playful jesting that distracted all their peers. At one point, Greg and Roy pitched an idea to form a New Product Research and Development team headed by them. Their bosses went for it, and very little was accomplished by the new division.

From the start, Follis and Carter loved gaming and sci-fi/fantasy culture. The pair often took mornings off to visit arcades and a science fiction bookshop called Dark They Were and Golden Eyed, trips that probably greatly influenced their future games. Their initial plan was to focus on Dragon computers, but the big success of the Spectrum led them to one conclusion: they had to make a sci-fi game for the new platform.

The original goal was to make games first so they could build enough capital to start writing business software; their legal company title, Carter Follis Software Associates, was professional enough to attest to this. Perhaps this objective had more to do with concerns regarding market security. Obviously, with all of their experience in programming and systems, they were older than the typical game developer. Although no source gives precise ages, the fact that Greg and Roy had been working IT together for 15 years when they started their company makes it clear that they were at least in their mid-30s. Often wearing suits and ties in their publicity photos, they had an air of professionalism that their younger peers lacked.

With Greg working on most of the game design and graphics and Roy doing the bulk of programming, Gargoyle Games was formed in 1983. Greg recruited a friend named Ted Heathcote to deal with the sales and marketing aspects of the company. Ted was a successful businessman, owning a large chain of menswear shops before becoming a “menswear agent” for big clothing companies across the UK. Evidently the transition was easy for Ted: he told Crash magazine that “menswear is really very similar to software”, a statement that might have been true in the early ’80s computer scene.

Initially, the company was based in Birmingham and all three men retained their full time jobs. Unwilling to accept the financial risks of developing and publishing games full time, their first entry into the Spectrum scene would be delayed until the spring of 1984. After months of late night coding, Gargoyle Games released Ad Astra, an arcade shoot-em-up with 3D effects akin to Sega’s Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom and incredible animations. As the game plays, the planets appear to be rolling toward the player, giving the rather typical game some gorgeous visuals.

Ad Astra did not reinvent the shoot-em-up wheel, and the public and press took note of this. While admitting that “there’s nothing new to speak of” in Ad Astra, Computer & Video Games also declared that it “deserves to do well” because of its “quality of graphics.” Although Personal Computer Games noted that many gameplay elements didn’t quite gel, they still came to the conclusion that the 3D effects were “superb.”

Technical achievements like these became staples of the Gargoyle catalogue. The focus on graphics was largely indebted to Greg’s short stint in art school prior to working in IT. The entire Gargoyle Games library is filled with fluid animations, something that many other games of the era ignored. In addition, Roy’s coding would go on to introduce a variety of techniques to the Spectrum world, although this wouldn’t become clear until their next game.

With the experience of Ad Astra behind them, the team decided to alter their approach. While working as systems analysts, Follis and Carter found and played a variety of adventure games on different mainframes. Their new idea was to make a graphical, inventory-based adventure game, a haughty goal considering the traditional graphic adventure was hardly set in stone. King’s Quest was months away and LucasArts wouldn’t begin their foray into adventure games for another two years.

Despite their initial success and acclaim, the Gargoyle graphic adventures are now often met with confusion or indifference. Their strange use of cameras and unconventional control schemes often cause people to reconsider their classification as adventure games and doubt their quality. Still, they remain an important stepping stone in the adventure genre and a technical marvel on the 48K ZX Spectrum. What Greg Follis and Roy Carter came up with melded together their diverse talents into a unified whole. Fluid animation, expert coding, and intricate design are the hallmarks of Gargoyle’s four graphic adventure games, creating a distinct style in a genre that relies far too often on typical conventions. While the unique qualities of the Gargoyle adventures make them worth examining, their excellence makes them worth playing.

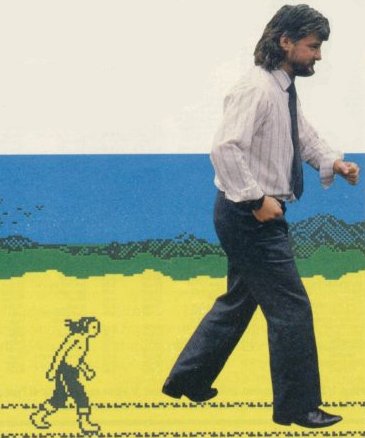

Greg and Roy gave conflicting stories about how development began on their first graphic adventure. In one interview, Greg states that he created a fourteen part animation of the “walking man”, which would become the basis for all player characters in future Gargoyle adventures. In another, Roy describes how he wrote a routine that showed a character walking in a scrolling background.

Either way, the next step was to determine a setting for this walking man. Originally given the generic title “Arabesque”, the game had no story until further into development. The Epic of Gilgamesh was their first idea for inspiration, but Greg and Roy quickly realized that Celtic myth was more relatable for their European target audience.

Greg Follis struts alongside the “walking man”

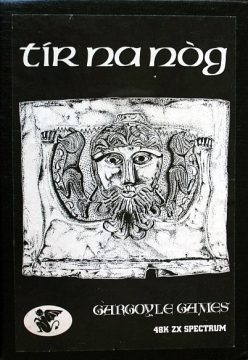

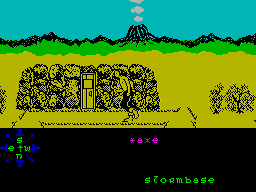

In Irish folklore, the Tír na nÓg, or Land of the Young, is a name for the Celtic Otherworld, a realm inhabited by deities and spirits. It’s the backdrop for many stories and an iconic part of Celtic mythology. The game’s hero, Cú Chulainn, is a prominent Irish myth hero, the archetypal heroic son of a god and a human. With setting and hero determined, the title became Tir Na Nog.

The rest of the story has no mythological basis and was largely conceived by Greg. The manual contains fictional extracts from the Leabhar Glaodhach, the Book of Tears, which details the game’s story.

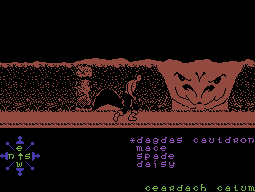

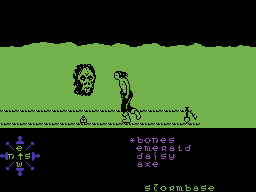

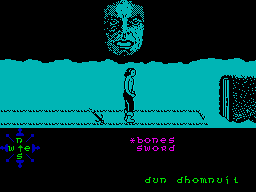

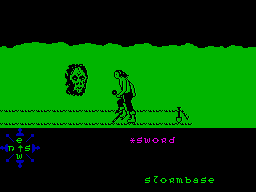

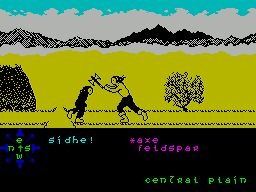

The Sidhe are a prominent race of people who take it upon themselves to emtomb the big baddie of the area, the Great Enemy using the Seal of Calum. Eventually, a thief steals the seal while the Sidhe are celebrating and the Great Enemy break frees and reigns torture across the land. After this tragedy, the Sidhe people become dark, simian-like creatures that roam Tir Na Nog, the afterlife.

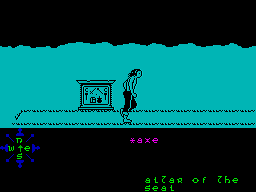

The remanants of the seal are shaped into four separate items: the Stone of Fal, the Spear of Lugh, Dagda’s Cauldron, and Nuades Sword. These artifacts do have a mythological basis as the Four Treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann. The mythical Tuatha Dé Danann were a supernaturally-intelligent race that inhabited early Ireland. Somehow, these four treasures wind up in Tir Na Nog.

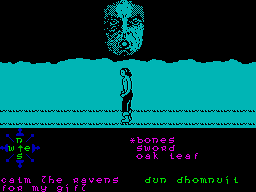

Cú Chulainn is killed by his enemies at the feast of Samhain and awakens in Tir Na Nog. He realizes that he has one last quest to complete: to unite the four fragments of the Seal of Calum, defeat the Great Enemy, and save the Sidhe.

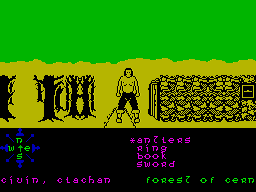

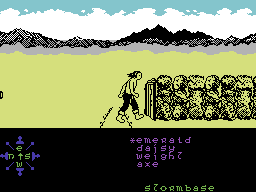

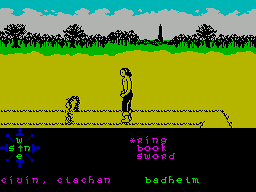

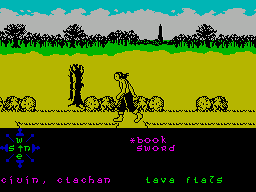

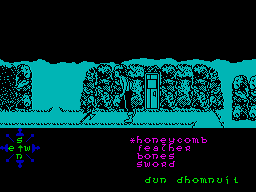

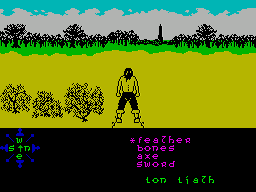

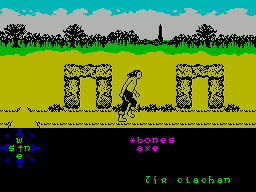

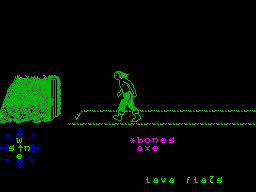

Even with the detailed story, the gameplay is more centered around Greg and Roy’s original animation than anything else. The “walking man” stays true to his title throughout, constantly going from place to place. The Gargoyle team estimated that Tir Na Nog’s roads equal 3,000 miles actual distance. While this seems to be a huge overstatement, the game remains vast, with hundreds of paths to take and dozens of caves to explore. Greg reported that the game is consciously winding by design: “we were trying to produce a real time environmental experience where the puzzles are three miles away from each other, not just next door”.

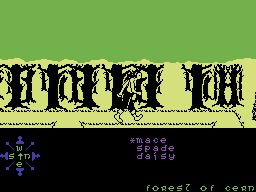

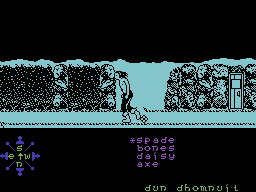

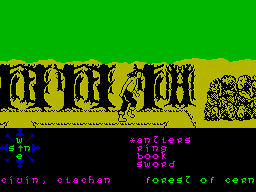

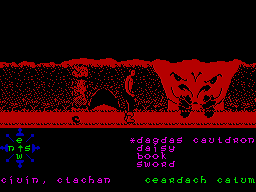

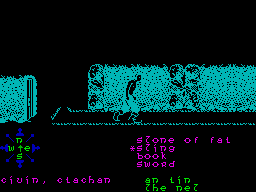

The game is always side-scrolling, but paths go off in all cardinal directions. To achieve this goal, the Gargoyle team programmed all the paths as simple vectors made up of north-south and east-west paths that intersect in various spots. To move to another path, the player switches to a cardinal camera perspective at any time. The camera switches at 90 degree angles, keeping everything two-dimensional throughout. Although navigation is difficult at first, a few minutes playing with the camera controls and several hours of careful mapping make everything much easier.

Even though walking is the focus, the stellar animation isn’t the only eye candy: the backgrounds feature some brilliant parallax scrolling, an almost unheard of achievement on the Spectrum. The background scrolls a thin band in the middle and clouds on top, which are all drawn onto an offscreen bitmap using the correct pixel offset and then quickly drawn on the screen. The game’s fifteen different sub-areas also feature different backgrounds, offering up more visual variety than the typical game. While this might sound pretty basic today, this was huge for the Spectrum scene circa 1984.

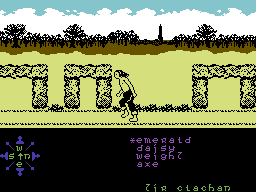

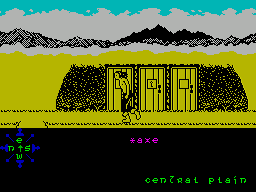

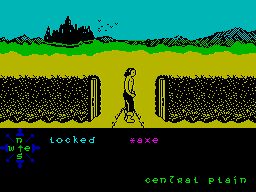

Tir Na Nog (ZX Spectrum)

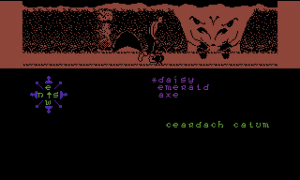

Inventory management is the game’s second core design element. Cú Chulainn has four inventory slots, and there are many keys, weapons, and other tools to fill them. Items, when picked up and dropped off elsewhere, will remain in that spot for the duration of the game. Eventually, juggling items becomes important, as you’ll need a certain key or weapon to reach new areas. Items are usually found in caves, but many can be found lying on roads, buried underground, or guarded by a monster. Some side-quests are available, but they are minimal and usually yield a weapon inconsequential to completing the game. All in all, it’s an inventory slog from start to finish, using item A on item B to get item C.

Figuring out what item A to use on what item B is where the game becomes deceptively difficult. Oftentimes, the player will stumble upon messages written on stones and scrolls across the land, few of which have any obvious answer. “Find my crown for a gift” might sound like you’re supposed to give Cernos his crown, but it’s never that obvious. He really wants a pair of antlers. “Linger by finger”, “key is cold then net unfold”, and “the backdoor key is me” are just some of the taxing hints that the game presents you. Suffice to say, many Spectrum magazines were filled with hints and tips to solve the game’s difficult puzzles. Only true adventure gamers with superhuman lateral thinking skills will be able to quickly ascertain the solution, and only after familiarizing themselves with every item found throughout Tir Na Nog.

Difficult puzzles aside, the only thing stopping Cú Chulainn from frantically grabbing the pieces of the Seal of Calum are his would-be friends the Sidhe. An axe or sword will always be needed to combat these dark beasts. Battle is incredibly superficial, with the player simply hitting a button to strike. The player can also humorously attempt to attack enemies with any non-weapon item found in the game. This isn’t advised, as hitting a Sidhe with a flower will only lead to problems. If the Sidhe ever touch Cú Chulainn once, all his inventory items are dropped in that spot and he re-spawns at the very beginning of the game. Since Chulainn’s already dead, he’s impossible to kill, but the anguish of having to retrieve crucial inventory items from far-off places is occasionally torturous. As the player can save at anytime, this rarely becomes a problem aside from the lengthy cassette load times.

While all of these options for movement, camera, and inventory may sound complex, the controls are relatively simple. The Spectrum’s three bottom keyboard rows perform separate tasks. The bottom row moves, the middle row controls the camera, and the top row picks up and drops items. Any of the Spectrum’s corner keys are used as an attack button. It’s quite different from most games, but in many ways it’s easier to manipulate than a shoddy text adventure parser or Police Quest 1.

Following the release of King’s Quest by only a few months, Tir Na Nog is one of the earliest graphic adventure games. With a basic inventory-driven gameplay and a simple control scheme, Tir Na Nog is as purely graphical as the genre gets. There’s no text parser, no environmental descriptions, just a brief story and exactly what you see on the screen. The imagery is stunning with stylish animation and great minimalist backgrounds, but it admittedly leaves many elements rather underdeveloped, specifically combat.

Still, the sheer size of the game world and sense of exploration it imparts is positively intoxicating. It’s very different from a typical ’90s LucasArts game, creating a tight-lipped, concealed world that refuses to give the player any easy answer. Mapping the area, experimenting with different items, and solving intricate riddles are enough to keep the best gamers busy for weeks.

Released in autumn 1984, Tir Na Nog sold very well on the Spectrum. One source claimed it quickly sold over 35,000 units. It was nominated Game of the Year in the Computer Trade Association Awards, and Roy Carter himself was nominated as Leisure Programmer of 1984. Reviews were uniformly stellar, and many magazines talked about Gargoyle as the next big thing. The game’s success allowed them to leave their jobs and dedicate themselves full-time to game development.

The release dates for other ports are difficult to determine. Shortly after its initial release, development of a Commodore 64 version was outsourced to Design Software. Based on reviews, the game was probably released around May 1985. This version suffers from some incredibly washed out colors, making it look much worse than the ZX Spectrum version. While many sources claim the Amstrad version was released in 1984, it was probably ported by Gargoyle themselves and released in 1985. This version sports a fully colored Cú Chulainn and gets incredibly choppy when there are multiple animations onscreen. Some sources erroneously claim that the game received an MSX port, confusing it with SystemSoft’s similarly titled strategy series Tir-Na-Nog.

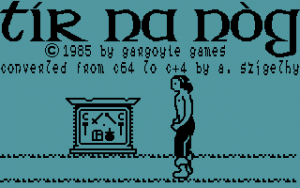

A fan port for the Commodore Plus/4 was made in 1988 by Andras Szigand, a prolific figure in the demo scene at the time. This version is similar to the C64 version, but the background image is drawn erratically along the edges of the screen as it scrolls. It’s rather distracting, but the game seems to be wholly intact otherwise.

As with any great 8-bit computer game, the Tir Na Nog cassette was constantly reissued over the years. Hewson Consultants’s Rebound label seems to have existed solely to reissue the Gargoyle Games library. They quickly re-published the game in 1986. It was also featured in the compilations Now Games 2 and the Amstrad Action Pack. It eventually was featured as the cover tape of Sinclair User 118 and Your Sinclair 65.