- Planescape: Torment

- Toment: Tides of Numenera

Warning: this article contains major spoilers for Torment: Tides of Numenera and Planescape: Torment

Torment in times of Kickstarter

As the success of crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter has allowed many industry veterans to pursue their own artistic vision and revisit once-forgotten genres, it seems that the mid-to-late-1990s style of computer RPGs has returned to popularity in mid-to-late-2010s. Tides of Numenera, a spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment, follows in the footsteps of Divinity: Original Sin, Wasteland 2 and Pillars of Eternity by attempting to both revive and modernize the gameplay and the narrative of the role-playing classics.

Like many crowdfunded games, Numenera‘s development was long and troubled. The game went through a very successful Kickstarter campaign (at the time it was the highest-funded video game on the platform), Steam Early Access, a release delayed by more than two years and a few fundamental changes which led to the game being available on consoles and having one of the initially small areas turned into a full-fledged hub levels but also to much of the content promised in the campaign (including areas and recruitable companions) not making it into the finished title. This, combined with the fact that it had to live up to its famous predecessor, ended up making the game very controversial among gamers.

When seen outside of the gaming hype cycle, Numenera is a game that shares many of its strengths and weaknesses with Pillars of Eternity, Obsidian’s spiritual successor to Baldur’s Gate. It’s a game that is more even and more polished than any of Black Isle or early Bioware titles – but it’s not as memorable. It solves many of the balance issues that could be found in the old game but in turns it makes different playstyles feel too similar to one another. The setting is intriguing, the writing is good and the story raises some tough moral dilemmas – but it ends up lacking much of the emotional impact of its predecessors.

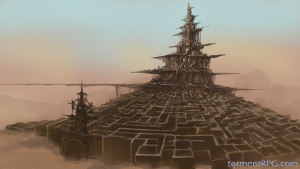

As Dungeons & Dragons license is now more expensive and more difficult to acquire than it used to be, we won’t be coming back to Planescape and Sigil in this game. Instead, the new Torment is set in the Ninth World – the setting of Numenera, a new (and also crowdfunded through Kickstarter) RPG system by D&D veteran Monte Cook. Despite apparently being set on the far-future Earth, it’s about just as weird as Planescape was, and even more disjointed. It’s a medieval fantasy world built on the ruins of eight vastly different and far more technologically advanced ones, with the eponymous numeneras – objects created in those worlds – functioning as magical artifacts. It is an interesting blend of sci-fi and fantasy, although while playing the game it’s difficult not to get the feeling that there isn’t much cohesive lore behind those worlds and that they’re more of an excuse to put literally anything into the game than anything in the Planescape multiverse ever was.

Re-thinking role-playing

Probably the best thing about Tides of Numenera is that, unlike many other crowdfunded RPGs, it doesn’t just blindly recreate the gameplay of the older games, instead attempting to innovate in some areas. As is often the case with such experiments, the actual results are mixed – but it’s the kind of ambition that made titles like Arcanumor, of course, the original Planescape: Torment stand out from the crowd.

Numenera’s characters belong to one of the three classes: Glaive, Nano or Jack. This has probably the least noticeable departure from the convention as despite a few technicalities (Nanos are expert on ancient technology, Jacks are supposed to be jacks-of-all-trades), it would be possible to replace those words with ‘warrior’, ‘mage’ and ‘thief’ without much impact on anything. The more notable change is how stats work: they’re now resources which can be used to increase a chance of success during combat and skill-checks (base values for success chance are calculated in a traditional way, through ‘skills’ and ‘abilities’ which can also be increased while levelling up) and get replenished only while resting. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work as well as it should – creating a party that can just keep succeeding is trivial, and despite many quests having hidden timers to prevent you from resting all the time, it’s actually pretty hard to fail a quest. The protagonist’s immortality doesn’t help the matters here.

The game’s combat system is based on a few really good ideas and, with some more polish, could actually become influential in the genre. During any dangerous and time-sensitive situation, the game enters turn-based ‘crisis’ mode. In this mode, all the characters present at the scene can move a specified distance and perform a single action. Those actions include the usual use of weapons and spells but not only that – they allow the characters to initiate conversation, interact with the environment or just run away. While the system’s slowness can be irritating, the encounter design is amazing – there are almost always multiple ways of dealing with each crisis and they don’t always involve fighting (a memorable one in the late game has you engaging in a turn-based negotiation between two hostile groups, making it possible to prevent bloodshed from happening). The whole thing is a great idea, and an obvious step forward from purely dialog tree-based skill checks.

Speaking of dialog trees, the game has no shortage of those. Not unlike Planescape: Torment, Numenera has a fairly large number of flashbacks – but now they’re interactive. When using a ‘merecaster’ (a device which allows ordinary people to revisit someone else’s memories and our main character to alter the past), the game’s normal interface disappears to be replaced with a visual novel-style full-screen static picture with text-based descriptions and choices. This isn’t a big departure from the previous game’s already text-heavy narrative – it’s more of a natural evolution (a VN interface is obviously better for such thing than a small text box on the bottom of the screen).

The fall and rise of the Last Castoff

Torment: Tides of Numenera begins with your character literally and metaphorically falling from heaven to earth – he was first created as a new body for The Changing God and gained consciousness when the body was abandoned. Not coincidentally, the protagonist’s fist memory is that of falling from the great height and hitting the ground (this is the game’s intro sequence and despite the main character’s near-immortality, it’s possible to get one of the game’s few game overs here by intentionally accelerating the fall).

The protgaonist’s divine origin is the central point of the game’s plot. In Numenera, you’re not the only living castoff – The Changing God’s former bodies keep living in the Ninth World, and they don’t get along with each other. There’s a neverending battle fought between the two factions of immortals, and their conflict centers around the attitude towards their creator. The question of castoffs’ identity seems to be the root of the problem as not even they know whether they’re separate, individual beings or just reflections of The Changing God.

While the questions the game asks about the characters are interesting, the same cannot be said of the characters themselves. They all have a basic personality, a few bits of backstory and maybe there will be a plot twist or two in their story arcs but there isn’t much beyond that. The relationships between The Last Castoff and the recruitable characters are a far cry from what could be seen in Planescape. In fact, the game’s most memorable character has to be Changing God himself – we discover his many lives just like we did with different incarnations of The Nameless One and it’s all really interesting but it’s also very loosely connected to the game’s much less engaging current events. This all makes sense thematically in a game about castoffs living in the shadow of their creator but it also doesn’t make for a story as powerful as that of The Nameless One.

The Last Castoff

Last in the long line of castoffs who gained sentience after The Changing God switched to a different body. Unlike The Nameless One, he (or she, as the game allows you to choose the protagonist’s gender) is more of an avatar for the player than a defined character. Like the protagonist of Planescape, he’s able to survive deadly situations, although now it involves a visit to a labyrinth inside of his mind. During the course of the game, he’ll have to decide the fate of all the other castoffs.

A nano focused on researching numeneras and The Changing God. As a result of her experiments, she is permanently stuck between dimensions and constantly surrounded by her ‘sisters’ – different Callisteges from parallel worlds, half of whom want her dead. She wants to abandon her physical body and become a part of the datasphere – a virtual reality network containing archives of all knowledge.

Aligern

Callistege’s former lover. He’s a bitter, sarcastic nano who used to be a priest until an encounter with Changing God led to the disappearance of his family and left him with strange, unexplained tattoos covering his body. He seeks revenge against Changing God and wants to find the truth behind the events that ruined his once-peaceful life. He will not travel with you if you have Callistege in your party.

Tybir

A jack who used to be a solider but is now earns his living through various shady deals – from smuggling to espionage. He’s a great liar, which makes him a rare (not just in this game but in RPGs in general) example of diplomacy-focused companion. During the course of the game, he’ll be forced to confront his past – especially how he betrayed his lover Auvigne.

A young girl (to young to even have a character class) who got lost in an unfamiliar dimension. She doesn’t remember much of her past but wishes to be able to return home. She ‘s always carrying an oddly-shaped stone with her and claims it’s Ahl – a god of running and hiding that she herself created. She’s good at stealth but completely useless in combat – that is, until her adult form returns from her home universe to help you. She’s probably the game’s most interesting companion, with a surprisingly complex and emotional story arc that actually wouldn’t be out of place in Planescape.

Comparing Torments

There are many ways in which Numenera is similar to Planescape. Sometimes they’re the ones that fans of the first game wanted to see: once again we have an immortal protagonist exploring a world that doesn’t quite work the way we expect, once again the game asks us heavy questions but is non-linear and open-ended enough for us to be able to answer them. When we reach the game’s third (and best) location – The Bloom, a living biological monstrosity which eats people (or aspects of them) and opens portals to different worlds – we even get a taste of the old mixture of personal stories and interdimensional travel. Unfortunately, most of the time we just see things that the classic game did better.

In Numenera, the main character has to live with the legacy (both the good and the bad) of Changing God who once inhabited his body – but it never hits as hard as The Nameless One having to deal with the consequences of his own past. City of Sagus Cliffs has its faction politics – but those factions are nowhere near as interesting as those found in Sigil. The Sorrow chases the castoffs the way shadows hunted The Nameless One – but it’s clear that it’s real target isn’t you but Changing God. Endless Battle between the castoffs is just like Planescape’s Blood War – but now we aren’t its victim, we’re a major power which will decide its fate. Big words like identity, death, entropy and memory show up here again – but there’s not much new to be said. More often than not, it’s just the same issues with a different coat of paint.

The audiovisual experience

The game’s graphics are a mixed bag. The main character is just ugly, and it’s not the same kind of ugliness that characterized The Nameless One – it’s just that both the model and the portrait are this shapeless, expressionless blob (the model is also devoid of any details, as if it was an early 3D render). Other characters, on the other hand, look fairly decent, with an occasional interesting touch which relates to their backstory – like the golden glow surrounding Erritis or ghostly images of sisters around Callistege. Most of the locations are pretty but also dull – with some exceptions like the hand-painted parts of The Bloom, although even that doesn’t reach the expectations set up by the amazingly creative and bizzarre concept art. With a few exceptions, the game doesn’t look as strange as Planescape (or rather those parts of Planescape when it didn’t make you run around the same few brown-and-gray slums) and it’s not as pretty as its contemporaries (e.g. Pillars of Eternity) to make up for it.

A large part of the game’s problems with emotional impact has to be the result of its soundtrack. It’s not that it’s bad, it’s just that it’s simply not as good as the one in the previous game. While I can recall some of the Planescapemusic (e.g. Deionarra’s theme) despite not playing the game for a while. there’s nothing similarly powerful and memorable in Numenera soundtrack. The voice acting, on the other hand, is really great – especially when it comes to Erritis and Rhin. Unfortunately, there isn’t much of it and the writing they’re given is simply nothing special.

What does one game matter?

It is difficult to judge Torment: Tides of Numenera. Without any biases and expectations that come with its Kickstarter campaign and the fact that it’s a spiritual successor to a cult classic, it’s a collection of neat ideas and interesting mechanics in a relatively well-polished (unless you’re playing a terrible console port) package that still lacks something in both gameplay and narrative that would make it a truly great title.

Unfortunately, the game itself doesn’t want to be its own thing. It’s not just that it’s called Torment – it’s full of references and callbacks to locations, characters, questions and themes from its predecessor. It’s constantly reminding you of a different game which already did most of the things it does, and did them better. It is, in a way, a castoff to Planescape’s Changing God. It’s inviting comparisons, and those comparisons are rarely (although not never – for example, there are no boring sections in which you’re forced to fight repeated enemies like in Curst Prison or Baator) favourable. The fact that despite a successful crowdfunding and lengthy development the game shipped without some promised content (there was supposed to be another companion, an underwater hub city and a crafting system) certainly doesn’t help.

Numenera is a victim of its own hype: it is a good game but it’s simply not as good as the thing people imagine when they hear ‘record-breaking Kickstarter campaign’, and ‘spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment‘ while at the same time looking at the amazing concept art. Paradoxically, it is too much like Planescape: Torment (when it comes to story and themes) to be judged on its own but to little like it (when it comes to mood and atmosphere) to be a worthy follow-up. Many of those sins could have been forgiven though if the game had a bigger emotional impact – but unfortunately and ironically, Torment isn’t good enough at tormenting the player.

Links:

Torment: Tides of Numenera official website

Torment: Tides of Numenera (for Planescape veterans) – a more favourable review at Rock Paper Shotgun

A less favourable review at RPG Codex

Developing a modern cult classic – RPGSite’s interview with Colin McComb