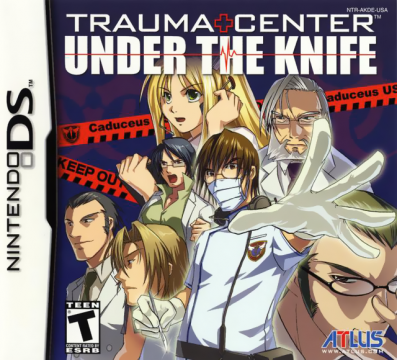

- Trauma Center: Under the Knife

- Trauma Center: Second Opinion

The unveiling and release of the DS, and later the Wii, was an exciting and anxious time for Nintendo and its players. Nintendo’s shift toward new control schemes seemed to signal a shift toward a new and different audience, and players worried that the challenges and stories of more traditional games would be left behind in the past. Trauma Center may have been the most successful counter-arguments, providing a fusion of unconventional controls and concept with fast, difficult action-puzzle gameplay.

Five games were released in the series, three of them starring the slacker surgeon Derek Stiles and his often overly-critical assistant, Angie Thompson. In each game, you begin at a small-town hospital, learning the ropes of basic surgery, removing tumors and sewing up lacerations. But, Atlus being Atlus, things quickly take a turn for the supernatural – our doctors discover they have surgical superpowers descended from Asculeipus, the ancient Greek god of medicine, and they find themselves in a battle against terrorist organizations unleashing man-made superviruses upon the world.

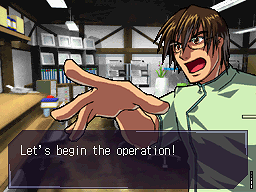

The series often comes up in the same breath as Gyatuken Saiban / Ace Attorney, and it’s not hard to see why. They were both introduced in the United States on the DS around the same time, offering dramatic anime-style spins on life in an otherwise ordinary-seeming career. And it doesn’t hurt that both of their protagonists do this a lot:

The series performed overwhelmingly better in America than in Japan, though sales declined overall with each new entry in the series (except for the final game, Trauma Team, which sold a bit more than its predecessor). After the first game, each title was released first in America, then Japan, then Europe many months later, if released at all.

You play as Derek Stiles, a young surgeon and one of many “DS”-initialed characters present in the handheld console’s early years. After carelessly putting a patient’s life at risk, Dr. Stiles finds himself at the scene of a car accident, where a mysterious power awakens in him, granting him the ability to slow down time. With the help of this power, the Healing Touch, he joins an elite medical organization, Caduceus, to combat a new epidemic of artificial parasitic infections collectively called GUILT.

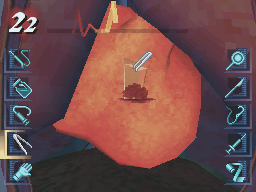

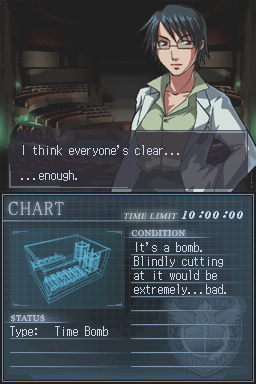

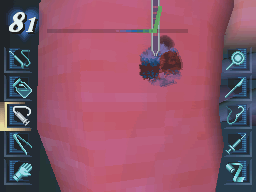

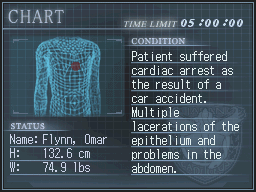

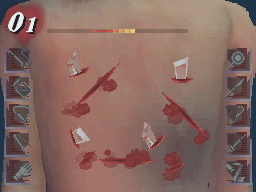

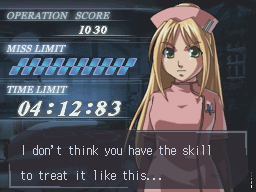

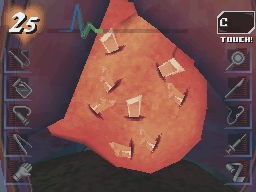

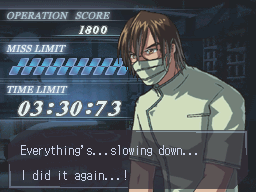

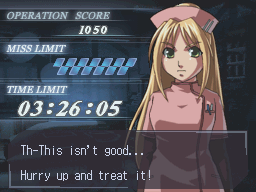

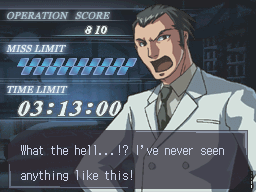

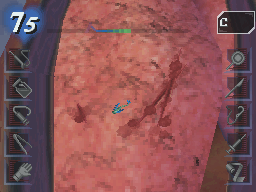

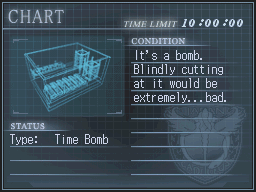

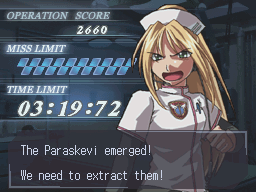

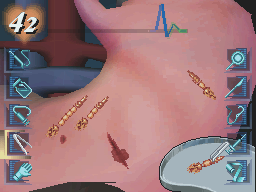

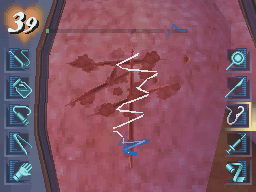

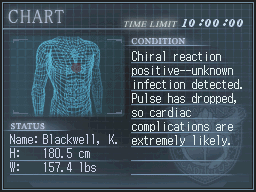

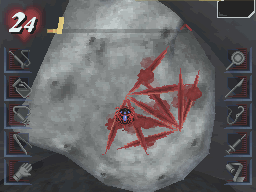

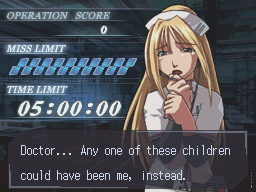

Each operation begins the same way: disinfect the operation site, then make the initial incision. You then enter a closer view of the organ in question. You might need to search with the ultrasound for tumors, suture lacerations closed, remove shards of glass, pin down and extract tiny thrombi moving through veins, etc. Your assistant, usually Angie but occasionally some other doctor, talks you through the procedure all the while, sometimes giving useful information but more often simply granting you a small reprieve from the action. Not only do you need to worry about your patient’s vitals, but there’s also a time limit and a “miss limit” – how many incorrect things you can do, from cutting outside the guidelines to simply putting the bandage on a bit crooked. The “misses” often subtract vitals and waste time, of course, so you are triply punished for your mistakes. After completing the mission and closing up the patient, you are graded from C (Rookie Doctor) to S (Master Surgeon) based on the time, the patient’s vitals at the end, and some special operation-specific criteria.

Surgery is a very natural application of touch controls – every motion feels fairly intuitive. Cutting across the screen with a scalpel, zigzagging to suture up a wound, drawing a serum with a syringe and pressing it down… it all feels very precise. Some specific motions can feel finicky, such as the game not recognizing specific suturings or sewing up a different laceration than you intended, but overall it feels great. Wrist strain definitely becomes a problem on some of the more hectic missions, particularly when a lot of suturing is necessary. Some players have even adopted the strategy of using a second stylus to distribute the work.

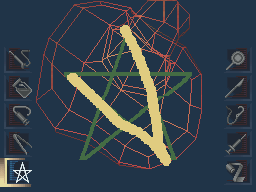

The Healing Touch, a signature element of the Trauma Center games, is introduced in this game. After a certain event in the story, you can draw a star on the screen and invoke the Healing Touch, temporarily slowing down time and highlighting the most crucial elements on the screen. It’s explained in the plot as a genetic gift given to doctors descended from Asculepius, the Greek god of medicine, giving them the ability of superhuman focus.

The game treats the Healing Touch as a wonderful ability with a great cost – Dr. Hoffman, the director of Hope Hospital who has the Healing Touch as well, warns Derek not to use it because of the tremendous burden it will place on him. The game, too, seems to discourage its use outside of emergencies – a significant score bonus is given for not using the Healing Touch, and you can’t get the highest rank, S, if you use it.

Under the Knife is an incredibly tense game to play. There is a lot of multitasking to do – should you treat the easiest lacerations first, or the more serious wounds that drain more health, or should you focus on stabilizing the patient’s vitals first? Wounds usually get worse when not attended to – lacerations open up, becoming covered with pools of blood. Luckily, the tension definitely comes in waves, granting you a brief repreive before the next set of the patient’s injuries reveal themselves.

The story of Under the Knife, like the rest of the series, bears the undeniable mark of Atlus. The game tackles some pretty serious subject matter: every surgery is a life-and-death matter. Not every patient will leave the operating table alive, either, despite your best efforts. But very quickly, while maintaining this life-and-death seriousness, the game introduces a lot of supernatural and sci-fi plot elements – namely, the Healing Touch and GUILT. This juxtaposition of serious melodrama and long, drawn-out conversations with dying patients with magical time-controlling powers is pretty jarring. In his parody of the series, Egoraptor animates the characters fighting “zombie cancer,” and he’s not too far off.

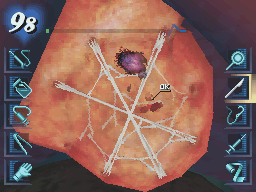

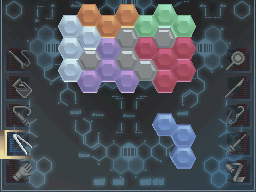

Though the tone they lend to the game is pretty unusual, operations on GUILT patients make up roughly half of the game, and they’re generally quite fun. They turn surgery into a kind of combat where scalpels and lasers are your weapons. As in the normal operations, you need to balance a lot of things at once, healing the patient’s wounds and trying to damage the GUILT. Each of the seven GUILT strains has different effects on the patient, and a different strategy for defeating them: the fishlike Kyriaki swims around in an organ and creates lacerations, and must be found with the ultrasound, excised, and burned with the laser; the infamous Triti forms a grid of triangular membranes on an organ, fastened with regenerating needles, which must be extracted in a particular way like a puzzle to prevent it from regenerating.

GUILT

In case the GUILT aren’t difficult enough the first time around, completing the game unlocks the “X missions,” a series of operations on even tougher versions of each strain of GUILT in order.

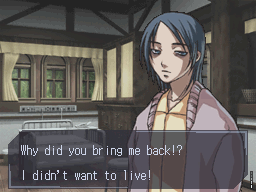

Derek and Angie save a lot of lives throughout the game. But one complication the game explores is that not every patient wants to be saved. One patient is suicidal, and is devastated to wake up again. One of Derek’s colleagues at Caduceus is secretly a practitioner of euthanasia, hoping to save his terminally ill sister from a life of pain trapped in hospitals, hooked up to invasive machines. And the game’s main villains, Delphi, argue that medicine saves lives that never should have begun; they spread GUILT to intensify natural selection and save the Earth from the effects of overpopulation and industrialization. These all begin as fairly complex issues without easy resolutions.

But these complex situations are all given easy resolutions. The patient’s suicidal thoughts were a symptom of GUILT, not mental illness; the euthanasia doctor’s sister ends up being curable in the end; and it’s hard to spend much time considering Delphi’s motives when they are revealed to experiment on young children kidnapped from third-world countries. The game showers you with unambiguous, uncomplicated priase for what you accomplish as a doctor; it feels great, but it feels cheap.

Some characteristics of Under the Knife as an early entry in the series are not particularly attractive, and were addressed in later iterations. For one, the difficulty is very high, but inconsistently so; the nearly-universal five-minute time limit for missions seems absurdly long in some cases, and very strict in other cases, particularly the Kyriaki missions, whose lacerations can stretch out the treatment time quite a bit. Additionally, this game has the lowest mission variety in the series. Before GUILT arrives on the scene, most of the surgeries are either finding and removing tumors or treating a large number of lacerations. There are a few one-off missions to treat thrombi or replace a heart valve, and these are fun for the variation they offer, but otherwise the beginning of the game offers little variety while you get up to speed on surgical technique.

The game’s visuals are unique within the series – the characters have manga-style portraits, the patients’ outer bodies are essentially Barbie dolls, but with internal organs that are three-dimensional, realistic, and bloody. There’s a bit of a disconnect here between the visual novel-style story graphics and the often grisly operations, but all the individual elements are successful enough. The game’s palette is fairly dull, predominantly the browns and reds you might expect. But the improtant elements on the screen stand out enough that the palette isn’t really an issue.

Shoji Meguro composed the music, which is a blend of synths, piano, guitar, and strings that should be recognizable to anyone familiar with his work in the more recent entries of the Shin Megami Tensei series. There isn’t much different music, but it is memorable and provides the appropriate tension during operations. Many of the themes introduced here get remixed in later entries of the series, particular the tense theme for the pre-operation briefing.

Just for fun, the localization gives many otherwise-anonymous patients the names of actors and characters on US medical dramas, primarily Scrubs and House. For example, the first patient, Kevin Turk, takes his name from Chris Turk, a character on Scrubs; the second, Noah Laurie, is named for Hugh Laurie, who plays House‘s titular character.

Under the Knife is a uniquely fun and challenging game, and a fantastic example of touch controls successfully applied to a hardcore game. But it is also the roughest game in the series, and can be terribly frustrating and repetitive. Because the enhanced remake Second Opinion is available, and addresses its problems with difficulty, pacing, and polish, it might be a better option if you only play one. But the dark atmosphere and style of this game is unique in the series, and worth a shot if you’re prepared for a rougher experience.

Links:

Atlus – Trauma Center: Under the Knife – Official site

Let’s Play Archive – Trauma Center: Under the Knife by World – a playthrough that earns all S ranks.

Characters

Angie Thompson

A nurse who transfers to Hope Hospital and becomes Derek’s assistant early in the game. She is kind with patients, but incredibly critical of Derek, holding him to a higher standard and helping him become a better surgeon.

Victor Niguel

An R&D technician at Caduceus, and responsible for many of the treatment techniques developed for the later strains of GUILT. He’s used to being the smartest person in the room, and hates to be outsmarted by his colleagues and viruses.

“Adam”

The impossibly old leader of Delphi, kept alive by a strain of GUILT called “Bliss.” Wants to grant humanity the “gift of death.”