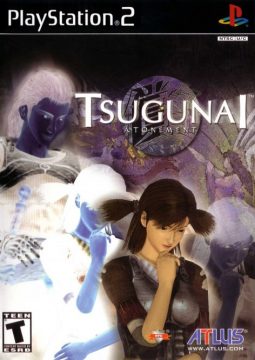

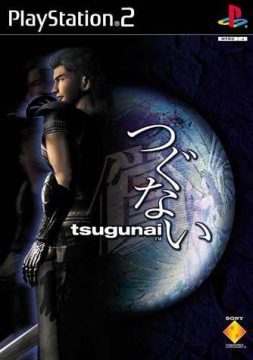

RPGs are long and take time to develop, so it’s rare that many are available at console launches. In the early days of the PlayStation 2, there were just a few titles, like Sony’s Okage and Atlus’ Tsugunai, to tide eager gamers over until the release of Final Fantasy X. In Japan, Tsugunai beat Square’s giant to the market by a couple of months, while its US localization didn’t appear until just a few weeks before it got pushed out and quickly forgotten. It very much has the hallmarks of a low budget, early PS2 title, but it’s an interesting game nonetheless.

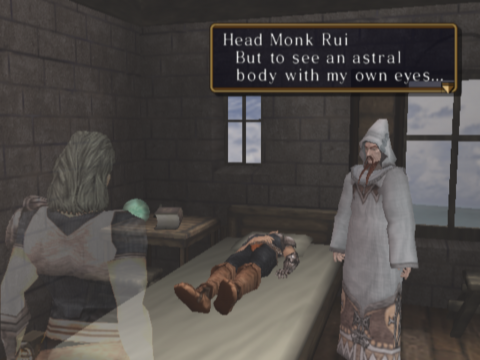

As a member of a mercenary corp known as the Ravens, our silent protagonist Reise is assigned to recover an ancient artifact for a powerful government leader, Lord Cole. This artifact, the Treasure Orb, is cursed. After stealing it from a guarded tower, supernatural forces separate Reise’s spirit from his body. His body winds up in a local monastery, alive but comatose. His spirit is helpless-unable to be seen, unable to speak, unable to interact with the world around him aside from being able to pass through light materials such as wood.

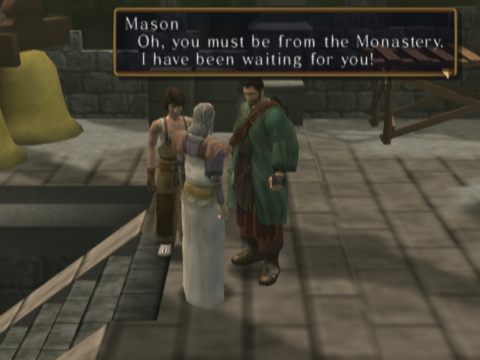

Thankfully, the head monk of this monastery has enough spiritual power to perceive Reise. He informs the mercenary of his strange position, that he has indeed been cursed for stealing the Treasure Orb. The monk then informs him that the only way for his body and spirit to be reunited is through demonstrations of kindness and courage. And in order to do this, he must possess the bodies of others and carry out tasks which they otherwise might not have the strength to do. These tasks range from helping a child find a cat to saving a lost soldier in a treacherous cavern. Thus, Reise heads into the local fishing village to atone for his transgressions.

As far as JRPG tropes go, two in particular seem to be pretty much a given for any major genre release: 1) Trotting through a variety of different locations-whether on different parts of the world or even planets and planes of existence-and 2) saving the day from an evil force bent on destruction or domination. Tsugunai: Atonement is a unique JRPG in its subversion of these generic expectations. In regards to the former, Tsugunai limits itself to one town and a few short dungeons. There is no world map. The town contains a mere handful of screens, with maybe a dozen houses, many of which you never actually need to enter and many of which are essential to one or two particular quests and little else. There is an item shop and a weapons and armor shop. There is no inn, or at least not an inn where you can heal your character as is traditionally expected. The monastery and the castle provide a little more than an average JRPG town, as the focal points for spirituality and power respectively, but even these locations are limited in access until key quests. You may train in the castle catacombs if you are in control of a combat character, but to explore areas outside the village Reise has to possess someone and talk to the gatekeeper.

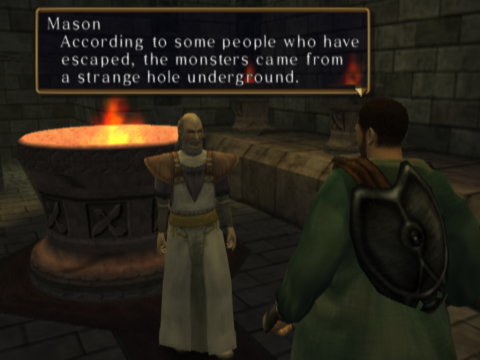

In regards to the latter trope, Tsugunai does still have a narrative about preventing an evil force bent on destroying the world. Or more specifically, resurrecting an evil demon. Let’s just say, Lord Cole isn’t exactly seeking the Treasure Orb for benevolent purposes. It’s obvious pretty much from the start. But this overarching narrative is almost an afterthought. For the most part you will be helping various characters through many interweaving sidestories. Tsugunai is much more about its slight world-building and character development, more about the banal day-to-day activities of a fishing village in a fantasy setting than it is about good versus evil.

Characters

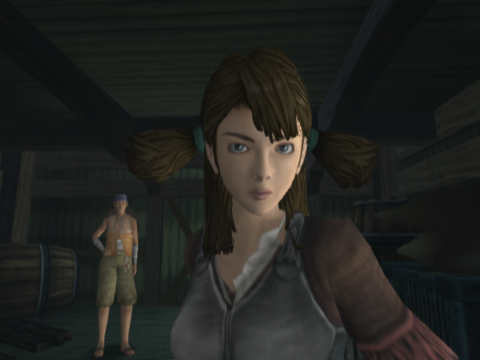

Fisela

A tomboyish young woman. Her story mostly deals with her strained relationship with her father, who seems to have checked out emotionally during her mother’s dying days. She fights with spears.

Ifem

A Raven with an immense amount of debt, accrued no thanks to his mother. His story is a progression of increasingly difficult mercenary missions, at the end of each of which the greedy debt collector takes your whole paycheck. His weapon of choice is the bow and arrow.

Ashgo

An apprentice monk. He is extremely clumsy and lacks confidence in his ability to even become part of the monastery. His story connects many of the magical aspects of the monastery’s gods and goddesses (particularly their powerful artifacts) to the overarching plot. Fights with a mace.

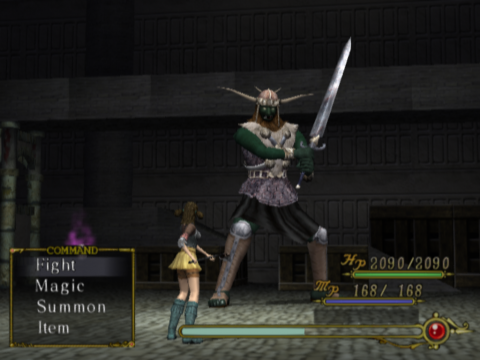

The battle system in Tsugunai is unique, incorporating proto-quicktime event gameplay. You control a single combatant, never utilizing more than one character at a time. While on the offensive front, the controls are business as usual-attack, magic, items, etc, as well as a sort of limit break bar-things get more complicated when you are on the defensive. Instead of having a percentage chance of an enemy attack missing you, the player has four buttons to press for four different outcomes. Press the button at the right time and you will be rewarded accordingly.

“X” is the standard defense. This has the longest buffer time, so it is the safest option to choose, especially when facing a new opponent. This merely decreases the amount of damage you take from an enemy attack. “O” will dodge. This allows you to completely avoid an enemy attack. It is more difficult to pull off, however, as it both requires more prep time and an amount of your limit break bar. “Square” is the limit build-up. If pulled off, attacks will hit for more than your standard defense, but you will build up your limit break bar faster. And “Triangle” will counter, which is the high risk, high reward option. If executed, you get to attack the enemy as well as defend yourself.

This system can be both a good and a bad thing. While it requires the player to get more involved in the nitty-gritty of fighting, keeps them attentive (like the ring system in the Shadow Hearts series), it can also make battles move exceedingly slow. The battle animations are slow to begin with. Tying this with the fact that it’s one combatant versus several enemies, even an ordinary battle can take forever.

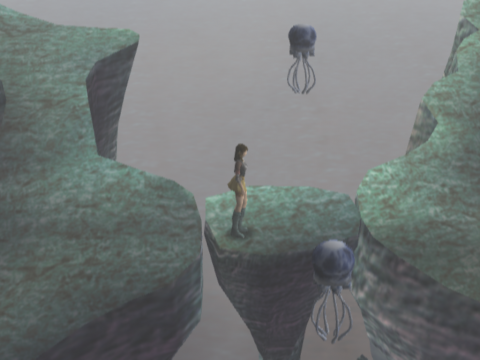

Another interesting aspect of the battle system is the summon system. As you go through the game, you’ll collect magic amulets. In order to use magic, you have to fit the magic “pieces” into each amulet’s particular shape. Some magic will be a square, others different sized triangles or a rhombus. Once fit together perfectly, you’ll be able to summon that amulet’s respective creature. These creatures act like a second party member, though you aren’t in direct control of them. Some will simply attack the enemy, others will give you status boosts or heal you. If summoned, they will also suck up a little bit of your magic power each turn. When your MP hits zero, the summon is simply rendered inactive. Ultimately it’s not that complicated, but it’s a pleasant added layer to the battle system, and figuring out which summons work best in a particular area can really pay off.

The game is split into 35 different quests. Only the ones involving Ashgo, Ifem, Fisela and Raffer require combat. Many are simply fetch quests, or just a matter of talking to people between several different places. It isn’t exactly an exciting game, but it does have a great deal of charm to it. The many little plots in themselves may not stand out as snippets of extraordinary storytelling, but they breath some life into the concept of a JRPG town. Unlike many JRPGs, where the town functions simply as a place to rest, gather materials and advance the narrative, Tsugunai‘s little fishing village becomes a character in itself. One really gets to actually dwell in the town, let its personality sink in.

Much of this town charm stems from the Celtic-inspired soundtrack, which was composed by the famous Yasunori Mitsuda. “Morning Fog in the Village” is a particularly representative track, exuding the same brand of calm and peace one gets from Chrono Cross‘s Arni Village themes. The graphics are early PS2 quality-a bit drab and gray, lacking much style-so this game actually leans greatly upon the strength of its soundtrack. Luckily, Mitsuda’s work here is almost worth the price of admission alone. One can take a listen on most streaming services under the name “au cinniuint”.

Aside from the aforementioned quirks and genre divergences, Tsugunai is at its core a pretty standard JRPG. The dungeons are simple, linear pathways interrupted by the occasional puzzle or key. Most bosses are merely larger versions of each area’s token monster, so it feels a bit uninspired there. It isn’t particularly difficult either until around the last quarter of the game. The difficulty spikes severely around the time you gain control of Raffer, and it can get nearly unplayable without some serious grinding. Late-game enemies can kill you in one hit if you fail to defend yourself at the right moment. It starts to feel a bit cheap, forcing you to restart from many faraway saves and making you be very, very neurotic about when to defend and which defense button you press.

The only optional areas in the game are the castle catacombs, where you can find several different caves to traverse. At the bottom of each you can find an additional summon and a cache of treasure. Unfortunately though, these areas are tedious and take forever. With no save points and a difficult boss standing between you and the rewards, it can be unnecessarily unforgiving to you and your time.

Tsugunai: Atonement is an interesting game for sure. It tries to do some things in a more innovative manner than other JRPGs, most apparently in its setting and the defense-centered battle system. But regretfully it suffers from many early PS2 JRPG pratfalls, such as its tediousness and the uninspired graphics. It was met with average to mixed reviews and sold poorly, and is now mostly forgotten. Despite its flaws though, Tsugunai contains a lot of elements worth checking out for the curious JRPG enthusiast. The approach to storytelling is admittedly a mixed bag-some stories, Ifem especially, just seem to sort of dangle there by the end without much feeling of connection to the rest of the game-but at least it tried something different. One can criticize Tsugunai for many reasons, but at least it’s not one of the multitude of trope-saturated JRPGs that have flooded the genre market before and since.