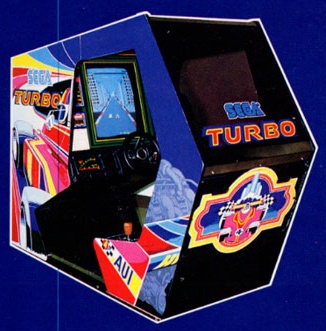

One of the more interesting video game genres is that of racing. As one of the earlier types of games to have become popular, racers are very simple by definition: Go fast, pass cars, don’t crash, drive far. One of the earliest games ever in the racing genre as we know it today is Monaco GP, one of the great Sega’s many early-day innovations. Its graphics were multicolored, its background scrolling was smooth, and it came in a fantastic sit-down cabinet back then which made it resemble actual driving. The real kicker is that this was back in 1979, and most other games only looked a step or two above Pong, whereas Monaco GP looked several million tiers above that. Sadly, the original arcade version of Monaco GP cannot be played as it was programmed entirely on logic circuits without a CPU. Thankfully, Sega’s next technical racing marvel, Turbo (no relation to TurboTime from Wreck-It Ralph), was programmed by the fantastic Steve Hanawa with an interchangeable CPU and still managed to look impressive, if not even moreso than its indirect predecessor. Turbo was also the grandfather of nearly every racer as we know them today.

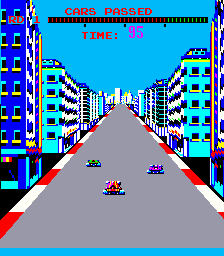

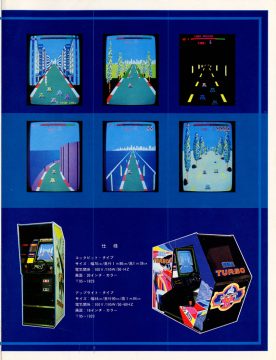

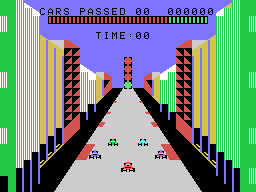

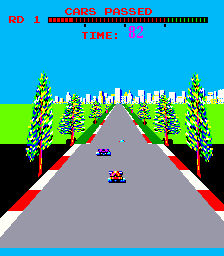

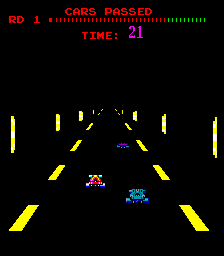

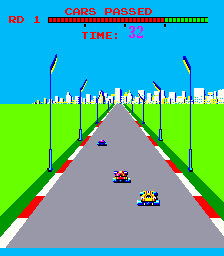

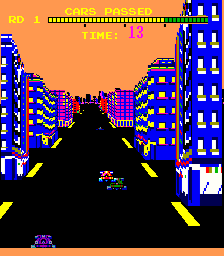

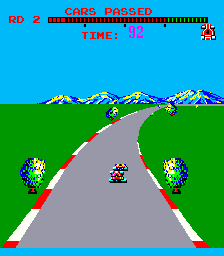

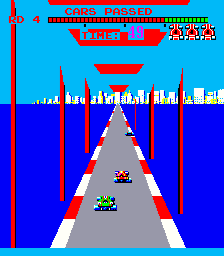

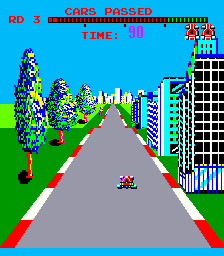

Most of the few racing games that existed around the time took a bird’s eye view of the vehicle, and some car-centric titles would continue this perspective like Spy Hunter, but Turbo began a trend upon which other companies began to clone. For a more realistic feel, the action takes place behind your vehicle’s tailpipe and you get to experience the rush of obstacles and rivals rushing by you. Atari’s Night Driver had experimented with a pseudo 3D view years before, but Turbo took the idea from the lonely ride along an abstracted road into a busy, zooming race. Turbo‘s foremost feature is its graphical prowess, which employs pseudo-3D effects in tandem with some smooth scrolling. It’s not quite yet to the level of the Super Scaler technology Sega became known for later: The central road stays mostly in place, while the stripes indicating the track edges wildly flicker by. On the sides of the screen are large city buildings and trees which grow larger as you drive past them, vertically scaling as they zoom towards and beyond the screen. Now while none of this may seem impressive by modern standards, bear in mind that this is a game from 1981, when most games were still just stiffly animated sprites against all-black backgrounds. Not that Donkey Kong and Tempest weren’t technical marvels in their own right, but what Turbo did essentially revolutionized the genre of competitive racing games as we know it.

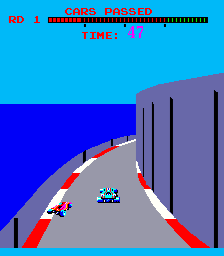

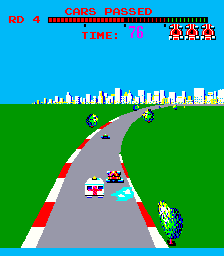

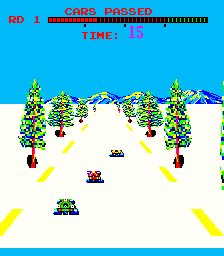

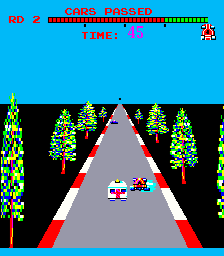

Not only did Turbo inspire the look of competitive racing games, but it’s also at the flashpoint of the insanely steep difficulty most such games warrant. The game predates the concept of the “goal line,” so you instead have to pass as many cars as you can before your time runs out. The bar at the top of the screen indicates a notch for every car you pass, and you have to try and earn enough notches so that you’ll reach the green portion of the bar. Getting hit by an obstacle, whether it’s on the track or on the side, will immobilize you for a couple of seconds. You can switch gears to help accelerate after a crash, but it can be rough to reach the first level quota. A feature that is simultaneously amazing and frustrating is that the scenery keeps changing, wherein you have to deal with hazards like lowered inclines where you cannot see part of the road. Sometimes, you’ll drive on the coast on a narrow curved road, you’ll pass under tunnels that hinder your visibility, and you’ll even drive through snow which takes a toll on your steering. Occasionally, a flag will warn you of an nearby accident, which means an ambulance will be rushing through, which has to be avoided. Later, puddles on the road also appear to hinder your progress.

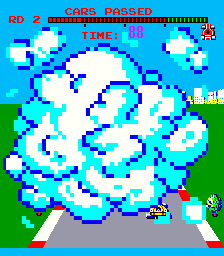

If you somehow manage to complete the first level, the game decides to quit holding your hand… or only then do you learn that it was actually holding your hand, as it is difficult enough to try and win the first round. Your further chances of winning plummet as you are now forced to drive with a limited number of lives. If you run into any obstacles from this point on, your racer explodes in a massive burst of smoke that zooms up in your face; you can only do this about two or three times before your game is immediately declared over.

While it can be tough to actually win, the experience of playing a technically advanced racing game from 1981 is gratifying. It may not look like all much alongside all the Ridge Racers and Project Gothams of today (or for even more realistic examples, the Gran Turismos and Forza Motorsports), but it is in part because of Turbo that these games have a presence. If you want a more historical example, a little Namco game by the name of Pole Position further popularized racing games with graphical effects similar to Turbo. However, while Pole Position is decidedly the more popular game, Turbo was released an entire year before Pole Position. Namco was more famed than Sega at the start of the eighties thanks to Pac-Man, so Pole Position and its sequel went on to a fair degree of fame, while Turbo was mostly left in the dust. Not that Pole Position wasn’t a great game in its own right, but it’s too bad that Turbo was mostly forgotten while the genre soared, especially within Sega. Thanks to Hang-On, OutRun, Enduro Racer, Power Drift, and later Sega Rally, the company’s presence among arcade racers became legendary. It would not be so if Turbo had never been made, so always keep it in mind next time you ever feel a need for speed.

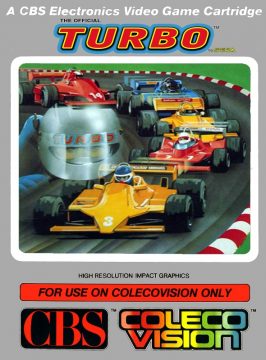

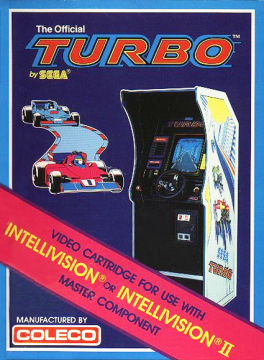

While Turbo never made it to any known arcade compilations, it did enjoy brief sustenance on the golden age console scene thanks to the ColecoVision. It actually was a big release for Coleco back in the day, and was bundled with the Expansion Module #2, a steerign wheel & pedal combo. As a machine oftentimes designated for bringing arcade experiences straight to home, this port actually performs admirably, even if the arcade’s butter-smooth scaling effects couldn’t be replicated. The action is still at least fast, and it even seems slightly easier than the arcade version, if only just. Coleco also licensed Turbo for release on the Intellivision, but the graphics are cruder and the scrolling effects choppier compared to the ColecoVision port. It’s still serviceable, but the CV was definitely the better of the two back in the day.

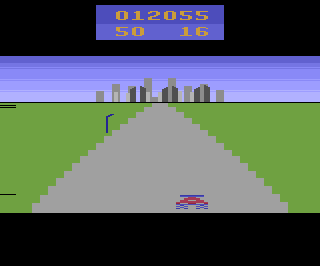

Atari 2600 Prototype (photo from Atari Protos)

Turbo was intended for release on the Atari 2600, however, it was never finished. It was partway finished when programmer Anthony Henderson got in a car accident, which unfortunately delayed the completion indefinitely. However, he was able to dig up a prototype indicating what it was to look and play like. It was originally played to use the paddle controllers, but since they were processor intenstive, they changed to a traditional joystick. While it is easily the weakest looking of the home conversions, reports indicate that it was a fairly decent effort for the platform.

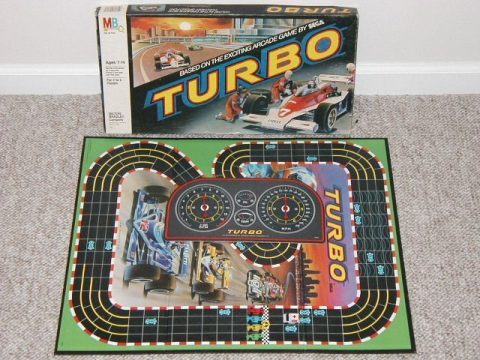

The oddest part of Turbo‘s legacy is the board game by Milton Bradley, though. Made for two to four players, it naturally couldn’t quite recreate the rush of the arcade game, but it was neatly designed nonetheless, with spinning speedometers replacing dice. Even the ambulance had a part in it, even though the board looked more like an official racing track, and not like the public road it is in the original.

Turbo board game (photo from BoardGameGeek)

Screenshot Comparisons