- Ultima (Series Introduction)

- Akalabeth

- Ultima I: First Age Of Darkness

- Ultima II: Revenge of the Enchantress

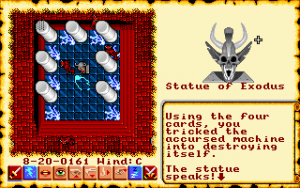

- Ultima III: Exodus

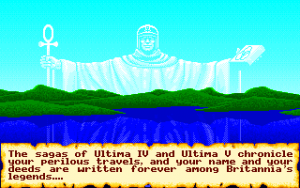

- Ultima IV: Quest Of The Avatar

- Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny

- Ultima VII: The Black Gate

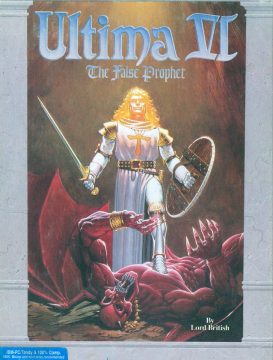

- Ultima VI: The False Prophet

- Ultima VII Part 2: Serpent Isle

- Ultima VIII: Pagan

- Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss

- Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds

- Arx Fatalis

- Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire

- Ultima Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams

- Ultima IX: Ascension

- Lord of Ultima

- Ultima Online

- Ultima: Escape from Mt. Drash

- Ultima: Miscellaneous

- Richard Garriott (Interview)

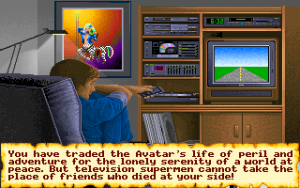

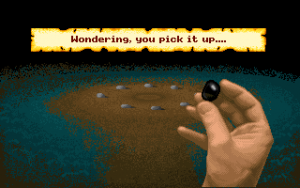

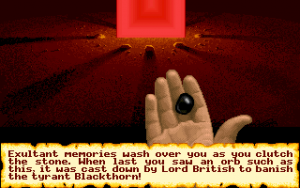

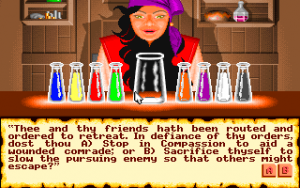

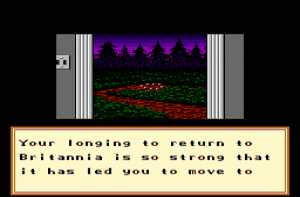

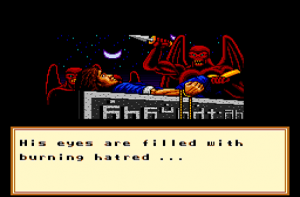

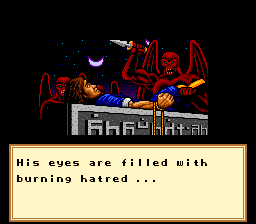

It’s been years since your last adventure in Britannia. Your perilous life as the Avatar has been traded once more for the quiet peace of Earth. But your life feels dull and empty, and you again find yourself wishing that Britannia would call once more upon you. As if in response, lightning strikes outside your house, and a moongate rises! It is red, not blue, but you don’t give this a second thought as you plunge right in. Britannia, here we come! Or is it? What is this strange, storm-covered land? What are these hordes of red-skinned, demonic beasts surrounding you? Wait, you’re strapped to an altar. One of the hideous monsters is chanting horribly from a book, and is raising a knife to strike you…

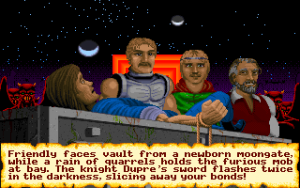

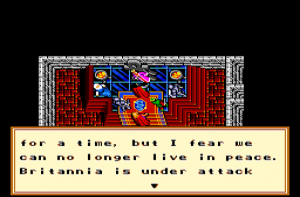

Like in Warriors of Destiny, Britannia is once again in dire peril from an outside threat. The player is rescued just in the nick of time by his old companions Shamino, Iolo and Dupre from becoming a ritual sacrifice for the skinless, fang-toothed, empty-eyed Gargoyles who, we are soon to learn, have recently begun attacking Britannia in force. The game has a fighting opening, as the creatures follow you into Castle British’s throne room and a bloody melee ensues; it is here that the real game begins, the first in the series to throw you into combat immediately. Such is indicative of the times: Lord British finds his armies stretched to exhaustion and, out of options, gambles on a hero like yourself finding a way to stop the attacks of the marauding hordes who threaten to bring a new Age of Darkness. You’ve done exactly that so many times in the past already, it shouldn’t be too much trouble, right?

It’s hardly a spoiler twenty one years after The False Prophet‘s release to say that what’s going on is a bit more complicated than it seems.

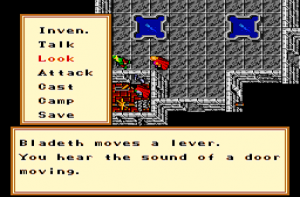

Ultima VI was a classic on release and remains a classic today, a terrifically fun game with astounding complexity and one of the best told stories in video gaming. Continuing to expand player options far beyond the previous game as each has done so far, the world interactivity makes yet another giant leap in The False Prophet. Ultima VI is the progenitor of the nonlinear open-world RPG that Fallout brought to prominence in 1997. Though you are given a goal at the start of the game and a pressing reason to pursue it, there is nothing stopping the player from simply wandering off to explore the world and see what they can find. Warriors of Destiny introduced the ‘look’ mechanic to allow the player to get a short description of whatever they saw, and The False Prophet adds to this with not only an even greater variety of world miscellanea but the ability to poke, prod, push, or pick up and take essentially everything. You can just as easily sit down for a meal at the Wayfarer Inn as you can kleptomaniacally steal every plate in Britannia and create a tower of them on Lord British’s throne (yelling “I am the king of the China!” is optional). Objects in the game all obey a set of physics rules, and have both side and weight (so good luck stuffing that expensive full-length mirror in your bag, Avatar). Besides the obvious “Save Britannia” there are plentiful side-quests and secondary goals to spend time on, and Britannia never feels like a static world existing only for you to come along.

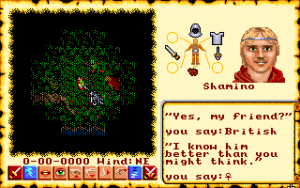

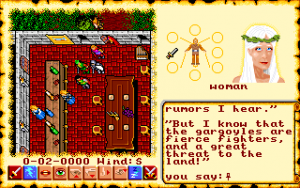

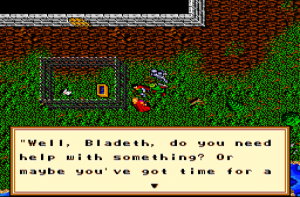

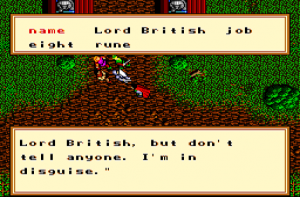

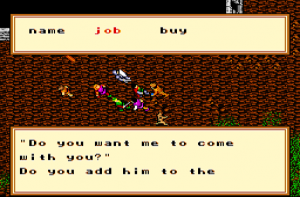

The script has been vastly expanded from Ultima V, with what feels like ten times as much text. Every NPC has plenty to say on multiple subjects and care has been taken to make even unimportant townspeople memorable. The first time you step outside of Castle British you’re likely to run into a peasant insisting that he’s Lord British in disguise among the people and asking for a donation to ‘keep up appearances’. Your Companions have more well-defined personalities, freely bantering among each other and occasionally interjecting in your conversations with their own comments. For the first time in the series you can start a conversation with people currently in your party and interact with them, a welcome feature sorely lacking in CRPGs in general and JRPGs in particular. Dialogue in The False Prophet is an in-between step between the ‘ask anything you like’ system of previous Ultimas and the ‘pick a keyword’ topic-based system of the later games and the console ports. You can still type any word as a conversation topic, but keywords are highlighted in conversation, taking some of the guesswork out of what to ask about next but retaining the ability of NPCs to hide secrets. Dialogue is now accompanied by character portraits of who you’re speaking to, which gives NPCs much more personality and leads to the opportunity for the occasional amusing Easter egg. (Doesn’t Shamino look kind of familiar?)

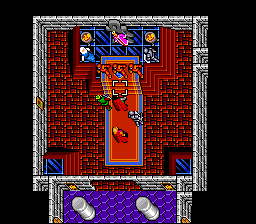

Ultima VI: The False Prophet is a technological paradigm shift in the series. As the first Ultima designed from the ground up on 16-bit platforms, the colors are richer, the graphics are more intricate, the script is longer, every character has a portrait. The size of Britannia is astounding, and it is quite possible to play the game for months without finding all the buried treasures hidden within. This sort of ambitious scale would not be attempted again until the mid-’90s with Bethesda Softwork’s Elder Scrolls titles. The familiar old tile graphics are gone, replaced by large colorful sprites viewed from a new isometric top-down angle, drawn with loving care by long-time box cover and manual artist Denis Loubet. The towns are normal part of the landscape instead of separate screens, and dungeons are no longer first-person-view crawlers; the entire game world is now seamless. It was a bit of a shock in 1990 to see towns as a to-scale part of the world rather than being single squares on a map that you entered, and made Britannia feel absolutely gigantic and very realistic.

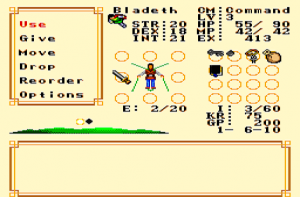

Mice were common and readily available on the PC in 1990 and the addition of mouse support in all versions makes the game easier to play for newcomers who haven’t yet memorized all of the (many) control keys. Though Ultima wouldn’t quite abandon the keyboard parser until the next game, it has been scaled down drastically. While previous games in the series made full use of the keyboard, with each of the 26 letters having some assigned task (and even more tasks in Ultima V requiring key combinations), The False Prophet is rather more player-friendly, with several commands folded down into just ten, many now part of a single ‘use’ command with the mouse handling much of the rest of the work. A subtle improvement to the game is the wealth of sound effects, which add shading and personality beyond the simple beeps of earlier games. The False Prophet was compatible with several popular PC sound cards, finally bringing to IBM PC gamers what Amiga, Atari ST and C64 gamers had long enjoyed.

The Age of Enlightenment trilogy of games have been described by Richard Garriott as a “virtue trilogy”, where Quest of the Avatar is about morality, Warriors of Destiny is about what happens when the government legislates morality, and The False Prophet is about social tolerance. There are no real final boss fights or climactic showdown battles in any of these, unlike very nearly every other computer role-playing game ever published since the genre’s inception. By 1990, computer games were no longer the niche province of a few companies making software for a narrow audience of technophiles. Ultima was competing with established titles like New World Computing’s Might & Magic and Strategic Simulation’s Dungeons & Dragons Gold Box games, as well as competing among a vast variety of other role-playing offerings that had taken Japan by storm in the wake of the success of Dragon Warrior there. The False Prophet stands out by the sheer complexity of the game world and the thought-provoking story, and even today it’s still a rarity for “role-playing” games to make the player think so strongly about exactly why a “hero” need go murdering everything in sight. Though the False Prophet begins feeling like a game from the Age of Darkness trilogy, with the Avatar leading Britannia against evil destructive invaders, this is eventually turned on it’s head when the identity of the False Prophet of the title is revealed. The dilemma of the Gargoyle invasion, while it seems fairly straightforward at first, eventually spirals into a situation where it’s hard to say who is right or wrong, and when the player learns exactly what they did to make the Gargoyles so terrified of him and Britannia, it’s hard not to feel like you’re the villain of the game. Of course, being the Avatar, you have the power to set things right.

Like with all previous games in the series, the previous code was thrown out entirely before starting from scratch. While this code reboot of each installment wasn’t actually intentional back for most of the series’ history, by the time of The False Prophet it was considered a defining trait of the series internally at Origin Systems. Ultima‘s early rivalry with Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead’s Wizardry series saw Wizardry gain a substantial sales lead over the first Ultima installment, but while Ultima‘s sales figures on average doubled for each new game, Wizardry‘s eventually slowed to a trickle towards the end of the 1980s everywhere except for a cult following in Japan. Garriott figured that this was because each Wizardry installment was essentially a continuation of the previous, while each Ultima gave players more and more new actions and things to do. Serendipity in design direction was what made Ultima win that early rivalry.

Stepping into the role of dedicated designer for The False Prophet in order to expand the game’s complexity as much as Richard Garriott’s imagination would allow, the actual programming work was done by multiple Origin Systems employees who programmed a game engine rather than a game, a combination framework and toolkit which Garriott and his designers then filled with content. In the present day when game design takes months or years, millions of dollars and hundreds of people, the use of an engine which the team then customizes to their needs and fills with content is standard, but in 1990 it was still more common for games to be coded as singular entities. This was a completely new approach for the series, and led to The False Prophet being the first Ultima that could easily be used as a base to make more games on. Later Ultima games would use this same approach and have their engines recycled for other projects, perhaps most famously Ultima VIII being the foundation for Origin’s Crusader series. Other teams at Origin Systems created a pair of spin-offs using the Ultima VI engine and released under the Worlds of Ultima label, putting the Avatar in strange new environments far away from Britannia. Worlds of Ultima was sadly short-lived; the games are discussed later in this article.

8-bit computer technology has finally failed to keep up with Ultima‘s increasing technological sophistication and complexity, and with a single exception The False Prophet is only available on 16-bit systems. The game was developed on and originally released for IBM PC, with ports to the Atari ST, Amiga, PC-98, FM Towns and X68000 following. For the first time in the series the Amiga and Atari ST ports actually look and play worse than the DOS. While PCs by 1990 had access to the 256-color VGA standard and were fairly clearly becoming the dominant computing platform (by crushing everything else in pure sales figures) the Amiga’s 32 color and Atari ST’s 16 color renditions of The False Prophet look dated and ugly. Much of the game’s soundtrack is missing on these versions and the game runs very slowly without being installed to a hard drive, which was an uncommon accessory among users of these machines. Most Amiga and Atari ST models simply didn’t have enough memory to run The False Prophet properly.

The last main series release by Pony Canyon in Japan, Ultima VI also got ports to the PC-98 and Sharp X68000. The only differences between these releases and the North American computer versions are the amount of colors and the Japanese text. Even in Japan, the computer industry was starting to embrace IBM compatible machines over formats like the PC-98 and MSX. As the ’90s went on, Microsoft’s MS-DOS and Windows operating systems only further established their hold over computer gaming, and we’re unlikely to again see something like Quest of the Avatar‘s fifteen different versions.

Fujitsu’s FM Towns port is a unique variant of the game. Besides being able to switch between English or Japanese text and having a bit of loading time, the FM Towns Ultima VI uses a keyword-based dialogue system modelled on Ultima VII‘s, and is the only version of the game with a voice track. The people from Origin provide voices for the characters modeled after themselves, with Richard Garriott playing Shamino and Lord British, Jeff Hillhouse providing Geoffrey, David Watson playing Iolo, and the like. This makes this version of the game theoretically a fantastic treat for fans, hearing what all these people actually sound like. Sadly actual deliveries are universally atrocious. None of the people providing voices are professional actors, and it shows in stilted tones and a general sense of amateurishness about the whole thing. The acting is in English, not Japanese.

The Commodore 64 port of The False Prophet was the last Ultima game developed for 8-bit computer systems, and managing to get the game to work on the C64 was a colossal feat. While IBM PC machines winning the platform race in 1990, the Atari ST, Amiga and especially Commodore 64 platforms still had plenty of users; the Commodore 64 in particular had an extremely large established userbase in Europe and failing to port the game to that platform would have meant a sizable chunk of lost revenue for Origin Systems. The False Prophet was never in development on Apple II due to the limitations of 8-bit processors, and now these limitations needed to be worked around.

Besides the obviously inferior graphical quality and resolution, the C64’s lack of proper mouse support (mouse peripherals on the Commodore 64 are treated as joysticks by the machine) means that the interface is completely different. Rather than the new half-parser and half-icon GUI, the C64 port returns to the old parser-driven interface used in the last six games in the series. A mouse or joystick can be used for targeting, but it’s awkward to do. Most damningly, though, is the way the game data is distributed. The game comes on three double-sided disks with divisions for start-up and character creation, Britannia’s surface and dungeons, the Gargoyle world and dungeons, and three sides dedicated exclusively to conversations. Every time you speak to someone in the game, you have to switch to the appropriate conversation disk and then switch back to the world disk when you’re done. This already rapidly becomes more of an annoyance, but the infamous slow loading time of Commodore 64 disk drives makes the game very difficult to play for anyone used to a more advanced version. A number of other gameplay features were cut for space, most notably the sound effects and music, successfully compressing the original game down to just over a quarter the size of the IBM PC original. Despite the extreme awkwardness of having to change disks with every conversation and sit through the load times, it seems that contemporary computer magazines were enamored with this version, seeing the excellent and groundbreaking RPG under the severe technical issues. Perhaps modern gamers just can’t handle load times as well. There’s a rumor on the internet that a glitch of some sort prevents the game from being beatable, but that doesn’t seem to be true.

Like the previous few games in the series, Ultima VI received a console port to a Nintendo system. Retitled Ultima: The False Prophet without the numeral, the game was released on the SNES/Super Famicom in 1992. Like the Nintendo ports of Exodus and Quest of the Avatar, the game isn’t quite as good as the computer original, but Origin did a much better job here at faithfully translating the original game to a console. The same approach as the Master System version of Quest of the Avatar is used here, with the same art style and as much of the original game structure left intact as was feasible for the limitations of the platform. There are cuts, of course. The intro has been abridged, character portraits have been removed, dialogue has been shortened to limit the amount of memory the script uses, and the interactivity with world objects has been reduced (there is no sitting animation, for instance). The controls have been changed to map to the SNES controller and there is no mouse support, even though a mouse for the Super Nintendo was released earlier that year as part of a bundle package with bestseller Mario Paint. Dialogue uses a branching keyword tree like Ultima VII and previous console ports due to the lack of a keyboard.

The most significant change in the port, and the one that tends to come up in fan discussion of the game, is the censorship. As is common knowledge, Nintendo of America in the eighties and nineties had a strict censorship policy to maintain their image as a family-friendly company, and this manifests itself in Ultima VI‘s script and graphics. Gargoyles no longer have horns, the gargoyle with a bolt in his head from the intro is removed, dead enemies simply vanish rather than leaving a body behind, and there is no blood or instance of the word ‘kill’. This essentially neuters the script, though not nearly as badly as it might have (see: Ultima VII‘s SNES port). The False Prophet is probably the best of the Nintendo console ports in how closely it resembles the computer original and is extremely cheap on the aftermarket; at the time of writing it could be found for about two dollars. It certainly doesn’t seem to butcher the original quite as much as the console port for the next game would.

Links:

Purchase Ultima VI: The False Prophet at gog.com

Notable Ultima’s release info for Ultima VI

Technical documents for the Ultima VI engine, hosted by Ultimaaiera.

Fan-made tools and an entertaining collection of glitches and tricks

Contemporary review of the C64 port

Ultima V for TI-89 and TI-92 calculators

Youtube video playthrough of the FM-Towns port of the game, including awful acting!

Comparison Screenshots – Lord British

Comparison Screenshots – Introduction