Introversion Software, the company behind Uplink (not to be mistaken with a Half-Life standalone expansion by the same title) is quite an unusual one: a small British software house created after most of the small British software houses dissolved and the market became dominated by AAA developers but before the indie boom and the popularity of crowdfunding which made businesses like that profitable again. When they made their first game, they couldn’t compete with big-budget projects as creating contemporary-looking games required manpower and technology they didn’t have but they also couldn’t just rely on nostalgic gamers looking for something more oldschool as the retrogaming market was much smaller than it is now (not to mention that current definition of “retro” is much broader than the one from the beginning of the century). The only way for Introversion to succeed was by making the kind of games nobody else was making – and this is exactly what they did, developing unique games about things ranging from hacking to administrating a prison to annihilating humanity in a thermo-nuclear war.

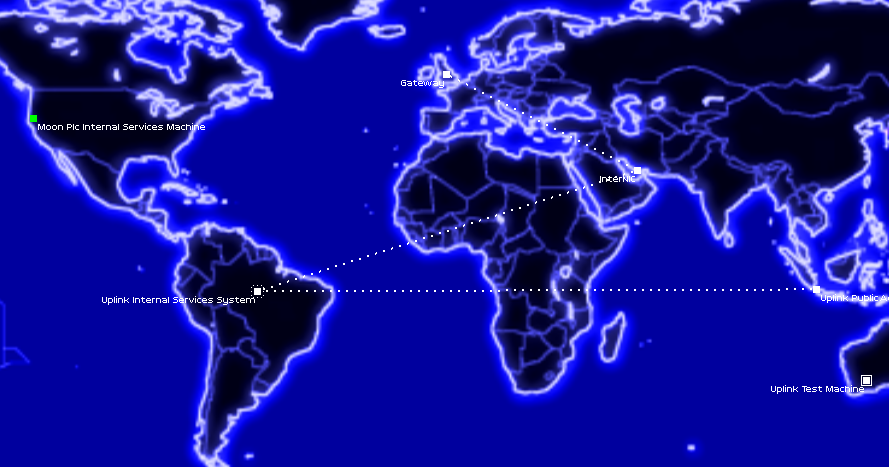

While Uplink might not be the first ‘hacking simulator’ ever created (System 15000 predates it by over 15 years), it’s probably the most important one as it codified most of the elements of this (admittedly pretty small as most games that feature the concept of hacking generally reduce it to a simple minigame) genre and popularized it among gamers. This was undoubtedly achieved in part by the game’s strong art direction: from start to finish, Uplink looks like a playable version of a hacker-themed movie like WarGames or Sneakers. It’s nothing technologically fancy – just a a bunch of buttons and menus, small text, a world map, a few static images and a dark background – but it nails the ‘computers in films’ look perfectly with its stylized interface, black and blue (with occasional red and green indicating failure and success respectively) color scheme, animated text and the occasional use of real photographs.

The game’s atmosphere is further enhanced by its soundtrack which consists of electronic/IDM/ambient music created using software known as trackers. Unsurprisingly for tracker-based music, all the songs were composed by people and groups related to the demoscene movement. They’re all pretty great, especially Karsten Koch’s track ‘Blue Valley’. Uplink’s sound effects consist of various high-pitched beeps and phone dialling noises as well as occasional speech samples when hacking voice identification systems. Like the graphics, those effects are nothing too fancy on their own but when combined with everything else about the game’s audiovisual aspect they serve an important role in creating Uplink’s trademark ‘Hollywood hacking’ feel.

All this talk about how Uplink feels remarkably similar to 1980s and 1990s hacker films fortunately doesn’t mean that the game has anything to do with the ‘cinematic experience’ trend in modern video games. While the game does look similar to how movies portray hacking, it does so without relying on cutscenes, scripted setpieces and linearity – it’s all seamlessly integrated into its fairly open-ended gameplay. Uplink is an immersive game, played through a diegetic interface – you start it by registering as an agent of the eponymous Uplink Corporation, you play it by using your in-universe computer and it ends when your character either manages to break it or gets disavowed by Uplink. Everything on the screen represents what the player character sees as he reads e-mails and news (the game’s way of delivering its storyline), buys upgrades for his machines and, of course, breaks into other computers.

Hacking is quite an involved process in Uplink. First, the player has to connect to the target machine – preferably by routing his connection through as many different computers as possible so that he won’t be too easy to find. After doing that, he has to deal with various security measures – sometimes realistic like a password that needs to be broken by brute-force (that is by trying every possible combination of letters) or a dictionary attack (by trying every password from a prepared list) and sometimes seemingly based in reality but really just using cryptography or computer security terms like ‘elliptic curve encryption cipher’ as a bit of technobabble. Security measures usually work in two different ways: they either prevent you from logging in or make it impossible to do certain changes to the system but dealing with them is similar – you need to run a specific program and wait for it to do its job. This is made time-sensitive by the fact that you’re being traced the way police procedurals think tracing phone calls work (complete with red lines over the world map if you buy a certain piece of software). After completing an attack, you should also delete logs on one of the computers you’ve used for routing the connection so that the police won’t find you a few days later.

The performance of your hacking arsenal (and its contents as you need to buy all the software) depends largely on the power of your CPU while some things are also affected by the speed of your internet connection. This of course means that hacking more difficult targets requires better equipment which you can buy through Uplink Internal Services System. You also need money to continue playing the game as a small sum is deducted from your account every month by Uplink Corporation. The hard way of making money is by hacking bank accounts – something that will usually end your game if you’re not prepared for it as the security is high and the police can trace you not only through logs but also through bank statements. The easier one is by taking missions ranging from stealing some data (which might require a better HDD as in the later stages of the game it can take a lot of space) to hacking into a criminal database and messing with someone’s records to get them arrested. Completing missions makes your Uplink rating (basically an experience level) go up and unlocks more missions in process while also having an effect on your Neuromancer rating (a karma meter which goes up if you attack corporations or government and goes down if you harm people, work against other hackers or help criminals) which doesn’t seem to do anything.

If Uplink was released today, its randomized missions combined with the fact that if you get caught doing something really illegal your save gets deleted (if you get caught doing something less illegal you’ll have to pay a fine and you get a criminal record which prevents you from accessing some missions – of course, you can break into Global Criminal Database and make yourself look innocent) would probably get it labelled as a game with roguelike elements. Unfortunately, it’s one of those games that don’t really benefit from procedural generation and permanent death. The randomization of missions just alters some names and the amount of money you’re going to get – thus, missions of the same type don’t feel too different from each other. You never learn the stories of your questgivers, there are no event chains or moral decisions (other than taking or not taking the mission that is). Permadeath does make things tense as after a certain point you simply can’t afford to fail but as each game plays more or less the same, it seems that the real punishment here is the tedium of doing the same early-game missions over and over again. The game would benefit either from dropping those things altogether (with no permadeath and fixed missions) or fleshing them out a bit more, making different playthroughs feel unique by increasing randomness.

While at first the game doesn’t really seem to have a plot other than ‘you’re a freelance hacker and you hack things’, the larger storyline gets revealed slowly as the game progresses. The central plot is related to the mysterious ‘Revelation project’ created by a shadowy Andromeda Research Corporation and the disappearance of hackers working on it. The player will either align himself with ARC or work for Arunmor – ARC’s enemies who’re trying to prevent Revelation from succeeding by developing a program known as Faith. Your choice can potentially influence the future of the whole internet as the game asks the question whether the possibilities given by a global computer are worth the potential loss of privacy as the government begins to use it for surveillance. Like with many classic cyberpunk stories, there’s something almost prophetic about its look at the future of the internet.

There seem to be no differences between the versions of Uplink made for different platforms, aside from the touchscreen control support for the mobile release (and the OS icon of your omputer when creating a character). There have been legal and financial difficulties between Introversion and Strategy First regarding the Hacker Elite version and Introversion claims that some mods and patches might not work with Hacker Elite but there’s no outside confirmation for those claims, even after Hacker Elite has been released on Good Old Games. It seems that aside from changed cover art, Hacker Elite is the same as all the other versions of UplinkUplink source code.

Uplink is an interesting game with an amazing atmosphere and some great ideas behind it. While after spending some time with it the repetition starts to become annoying, the first few hours of playing it are genuinely great. The game’s success is what put Introversion on the map and allowed them to release other memorable titles like Defcon and Darwinia. It’s definitely a game that’s worth playing although it also makes you wish there was more content in it (an issue somewhat solved by a dedicated modding community). Despite some of the flaws, it’s worth remembering that almost every modern hacking-themed game – from the obvious spiritual successors like Onlink or Codelink to things like Digital: A Love Story – owes a lot to Introversion’s first game.

Links:

Uplink official website

The ultimate guide to Uplink

Hacking in Uplink at PC Gamer