PlatinumGames’ Vanquish is very heavily informed by the time and place it comes from. When it was first released in 2010, the game stood out as a Japanese game in a non-Japanese genre. The shooting genre was dominated by American games like Halo, Call of Duty, Battlefield, Gears of War, and so forth. While the East/West divide Vanquish pointed to wasn’t the only talking point about it, it was definitely a recurring theme in many of the discussions surrounding the game.

Given the state of shooters at the time and the ways Vanquish sets itself apart from its peers, these comparisons aren’t without merit. Still, they risk exaggerating how representative (if at all) the game is of Japanese culture. On the one hand, it bears PlatinumGames’ unmistakable stamp. That’s likely why Vanquish is hailed as a cult classic: because of how all the studio’s minor inflections interact with the strong third person shooter base. On the other hand, the game isn’t as distant from American shooters as critics have made it out to be. It still reflects many of the design trends that were popular in those other games, both for better and for worse.

Maybe the easiest place to see Vanquish‘s Japanese qualities (in a very broad sense, at least) is in its narrative. The story takes place at an unspecified point in the near future. The United States has reached new heights, both metaphorically and literally. The launch of its space colony and 51st state, the Providence, allows the country to send cheap solar energy to its other 50 states. By contrast, Russia finds itself burdened by overpopulation and political instability following the Cold War. Eventually that burden proves too much to bear as the Russian government is deposed by a military group known as the Order of the Russian Star. After their coup, the Order takes over the Providence, turns it into a weapon, and fires that weapon on San Francisco. Threatening to do the same to New York City, the US government sends a group of Marines and DARPA soldiers to return the Providence to American hands.

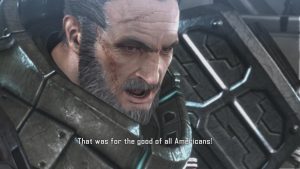

The hero of the game is Sam Gideon. Recruited into DARPA after an injury cut his football career short, Sam is equipped with state-of-the-art military technology and leads the mission against the Order of the Russian Star. He’s essentially the aloof action hero whose disaffected attitude allows the player to enjoy the absurdity behind each situation. It’s also worth mentioning he bears a slight resemblance to Sam from Metal Gear Rising. He’s joined by Elena Ivanova, a support character who provides logistical aid, and Robert Burns, a commanding officer from the US Marine Corps, and a hyper-masculine military figure who prefers brute force, immediate action, and raw strength to nuanced tactics, something he criticizes Sam for throughout the story. (In addition, some of Sam’s squadmates get amusing names like Shinji Mikami or D. Grassi.)

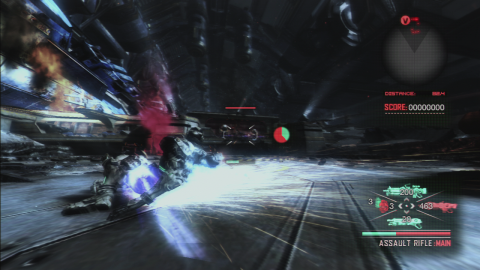

When the game begins, it’s clear that it’s trying to mimic something like Gears of War, but simultaneously, there’s a sense of style that seems uniquely Japanese (or at least, distinct enough from other American games). For starters, despite the heavy military technology and presence of large, stomping robots, it’s actually quite bright, to contrast the brown-and-grey color palette these games otherwise utilize. There’s also an intensity to the way that the battlefield is presented – bullets are presented as projectiles, rather than just using the invisible, hit-scan function. Missiles blast around in every direction with Itano Circus-like rocket trails. When the screen is littered with fire, friendly or otherwise, you don’t even need to be running and gunning to feel the exhilerations; merely existing in the game world is enough.

The central mechanic of the game is like if someone at Platinum looked at Gears of War‘s “roadie run” and decided “how can we make this cooler?” So in Vanquish, Gideon has a “power slide”, which now only sends him rocketing forward, but can also slow down time using the Augmented Reaction (AR) function, allowing you to carefully aim while you’re zooming across the battlefield, like a jetpack equipped, cybernetic Max Payne. It has numerous uses than just getting from directly Point A to Point B more quickly, as you can use it to quickly retreat or attempt to hunt for cover if you take too much damage. In most moments, you’re also accompanied by your fellow warriors, who don’t have the same awesome abilities as you do and tend to get killed. Just rocket on over to patch them up, and they’ll join back in the fray.

From a narrative perspective, Vanquish is heavily inspired by American action movies and deluge of media satirizing them, Metal Gear Solid in particular. (That latter affinity is so strong that it makes Metal Gear Rising look inevitable.) From a mechanical perspective, its sources of inspiration are more diverse, pulling from contemporary shooters like Halo 3 and Gears of War, to older games from the 80s and 90s. Particularly, the moments when you see a large enemy robot open up its chest and spew a gigantic laser around the battlefield. Or the jeep that, when its back is turned, will reveal a large red weak point. In many ways, Vanquish is Gears of War by way of Contra III. Aesthetically, it draws from manga and anime too, of course – the cylindrical space colony is heavily modeled like the type you’d see in Gundam. Yet the game doesn’t blindly mimic what its predecessors did. In fact, it will just as often make very important breaks from the trends they were following.

For example, Vanquish has a sense of humor that many other games lack. Those other games may have a funny moment scattered here and there, but Vanquish‘s comedy is consistently applied across the entire experience and delivered with an apparent amount of flair. The robot dancing easter egg, aside from fitting an ethos Vanquish develops elsewhere, is warm and cute in a way that games are tailor-made to capitalize on. The closest parallel from American shooters to this game’s sense of humor might be the football scene from Gears of War 3 (released one year after Vanquish), although even that comparison leaves something to be desired.

To be more specific, both games speak to a much broader trend in video game design that Vanquish is reacting to, consciously or not. It’s widely understood that American shooters were hailed as the vanguards of video game realism, and that they often would often comport themselves with a degree of self-seriousness. Their worlds were doused in gritty textures, and their protagonists would step foot into those worlds with a conspicuous thud, as if the game wanted to impress into its players just how real the action was. Whether or not shooters deserved such a reputation (and what other goals those games had in mind) is a separate matter altogether and almost certainly varies on a case-by-case basis anyway.

What’s important is that Vanquish functions as a reaction against this nascent ideology. It’s happy to borrow the disorienting spectacle a lot of these games were known for, but it never once thinks of pursuing their self-serious realism. Vanquish‘s logic is different from that: it sees the visual arts (animation in particular) not as a prompt to mirror a single idea of what’s real, but as an opportunity for creative expression. Hence it cuts anything it feels is unnecessary and exaggerates whatever features it happens to be interested in.The results of this approach should be plainly visible: where other games demanded that they be taken seriously with a rough, dirty art style, Vanquish aims for what it finds is aesthetically pleasing: smooth mechanical surfaces. Its greys are brighter and more colorful with subtle tints of blue, green, yellow, etc. Bullets visibly whiz through the air, and some of the boss battles climax with a Macross-esque spray of missiles. And from an animation perspective, movement feels bizarre. Characters in hulking armor traipse about the Providence with an unexpected quickness, their suits only weighing them down when you wouldn’t expect them to.

As unsuited as this approach is for capturing the there-ness contemporary shooters sought, it’s a perfect fit for the game’s theatrical, fun-loving nature. Animations have a strong presence not because they allow you to believe Sam (your avatar) really is an extension of your own being, but because their quirks make Sam’s personality all the more palpable. Vanquish‘s intelligent use of Quick Time Events to accentuate the action render that personality all the easier to read, but the Power Slide provides a much better example of this in practice. Sam’s laid back animation during the Slide matches his trivial relationship with the environment around him.

The narrative carries things even further, at least insofar as Vanquish even has a narrative. There’s a decent argument to be made that it doesn’t. The story doesn’t have much in the way of plot or character arcs, and few of the original premises hold any relevance as the story advances. And with the Providence floating out in space, divorced from any larger political context Earth might supply, the animosity between Russia and the United States becomes completely unnecessary to understanding the story. The result of these decisions isn’t so much a coherent narrative as much as it is a series of opportunities for the story’s actors to give the most passionate performances they can.

No wonder, then, that Vanquish‘s greatest asset is its unreal sense of spectacle. That’s the force that breathes life into the game, No longer tethered by the strict confines realism would have placed on it, Vanquish is free to celebrate its own unlimited potential. In its jubilee, the game is imaginative, over the top, and enthusiastic; so much so that you feel yourself sucked in, wanting to have just as much fun with the game it’s having with itself.

Read in context, this approach allows Vanquish to realize things its contemporaries could never hope to accomplish. Where shooters hide their roller coaster design approach beneath the surface like a shameful secret, Vanquish draws that approach up to the surface to get everything it can out of it. (Act 2 is a strong example of it in action. The Providence’s curved architecture allows for tracks to bend and gravity to twist as the designers see fit.) This is, again, an element that recalls classics 80s and 90s game design. Read on its own terms, the game’s a celebration of the post-human condition, or how much power technology has to expand humanity’s potential. And in that regard, Vanquish is a perfect synthesis of form and function: every ounce of the game’s energy is being used to realize that idea wherever and whenever possible.

Of course, there are problems with interpreting the game as representative of what an entire culture is capable of creating, or as little more than a reaction to trends American developers set into motion. Vanquish isn’t just a third person shooter from Japan; it’s a third person shooter from PlatinumGames. More specifically, it’s a game from their earlier period: it was released during their second year in existence, one year after Bayonetta and Madworld and long before some of their more iconic titles like Metal Gear Rising and The Wonderful 101. Even at this early stage, Vanquish clearly reflects a lot of PlatinumGames’s design philosophies. Its style of play is highly technical, every facet of the experience calculated down to the last detail. But it’s not polished, per se; the connotations behind that word imply the game focus tested away all its flaws, idiosyncrasies, and any hint of self expression to appeal to as wide a swathe of people as possible.

If anything, the opposite holds true: Vanquish confidently presents itself to a very specific set of players, one it believes would be comfortable navigating all its technical details. While the results may superficially resemble what its peers were doing, the nuances are unmistakably Platinum. For example, consider the fuel system that ties together the Power Slide and the Augmented Reaction mode. The concept is fundamentally similar to the idea of regenerating health, but with two key differences. First, both the Power Slide and AR draw from the same energy pool; draining one will drain the other. Second, you can activate AR at will, something the game highly encourages. In addition to the added tactical nuances (especially when aiming for higher scores), these systems allow you to control the speed of play, ranging from the Power Slide’s rapid pace to the measured progression of AR. These features encourage direct and highly controlled action as opposed to conflict as a distance.

The weapons, meanwhile, let Vanquish express its enthusiasm and its sense of humor while adding minor strategic touches to play. You have your run-of-the-mill assault rifle, your close-quarters shotgun, your rocket launchers with delayed lock-on features, your sniper rifles, grenades (both regular and flash), etc. Any weapon outside this menagerie tends to be more fantastic in nature and to play into Vanquish’s specific design. The Disc Launcher cuts through close groups of enemies and is indispensable to melee combat. The LFE Gun performs a similar function by stunning enemies with a giant ball of electric energy. The Lock-on Laser, with its Panzer Dragoon-esque paint-the-targets functionality, makes taking down widely spaced out foes (or one beefy foe) easier. Means of attack that don’t rely on ammunition play into Platinum sensibilities even further, whether that’s draining all of Sam’s fuel to punch an enemy to death or throwing a cigarette into their face to shave off that last sliver of health.

But it’s the way Sam upgrades his weapon that really demonstrates how Vanquish‘s brand of action differs from the crowd. The broad strokes are very similar to what other contemporary shooters were doing: not counting his grenades, Sam can only hold three weapons at a time, meaning he’ll often use whatever weapons the enemy’s using to ensure he doesn’t run out of ammo. Vanquish complicates this set-up with its upgrade system, where picking up a weapon when it already has full ammo will permanently upgrade that weapon. It might gain more firepower, it might reload more quickly, it might have a larger magazine, etc. This system allows Vanquish to achieve two things. First, by emphasizing the weapons beyond their immediate use, it becomes easier to appreciate all the little quirks in how they handle, giving those weapons a strong presence. Second, the system introduces a tension between short term and long term that enhances tactical thinking. Do you prioritize making Sam’s weapons more powerful in the long term by reserving one of his weapon slots for an upgrade-only weapon, or do you make full use of his arsenal for whatever conflict he’s currently embroiled in? Unfortunately, the scoring system isn’t as fortunate as either of these other two features. It lacks too much context to work like it does in many other action games (Metal Gear Rising, Devil May Cry, Bulletstorm, etc.)

As much as these two factors – the unreal spectacle and the finely tuned Platinum gameplay – help the game, they also introduce problems that Vanquish has trouble addressing. The most pressing of those issues is also one of the most mundane, as far as shooters are concerned: a refusal to engage with politics the game itself brings up. The game celebrates all of the awesome action hero stuff your character can do, but the world was always designed to avoid its own political implications, whether that’s by reaching into the past with Cold War politics or by extending the action into the future, where presumably the present situation doesn’t apply. (This is the same fallacy Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare would later commit.) It doesn’t help that it’s never clear if the game is making fun of Western-developed meathead military shooters or embracing them. It has many of the same dumb characters and dumb scenarios, but it can’t decide whether the portrayal is intentional or ironic. As such, if there’s any intended satire, it doesn’t really work.

It may be unfair to blame Vanquish for all of these problems, given how rampant they were in its genre of choice, but many other games were already incorporating those critiques into their design. Those deconstructive games had either been out for years (BioShock, Braid, the Metal Gear Solid series) or were just a few years away from seeing release (Spec Ops: The Line). It’s clear that PlatinumGames is far more in favor of spectacle than serious thinking, but with the other ways it ribs on Western shooters, it can’t help but feel like a missed opportunity.

Despite an obvious set-up for a sequel, PlatinumGames has never announced plans to follow up on Vanquish. The game received high marks from critics (though not as high as other Western developed shooters) and the sales were never quite spectacular. It had a problem that there were too many other shooters at the time, and only so much attention that could be paid to them. It was lacking the multiplayer elements that turn those type of games into multi-million sellers, and it’s not the type of genre that most fans of Japanese game fans would typically be into. Then again, the market was crowded, and even Western-developed games that also got high marks – like People Can Fly’s Bulletstorm, which has a similar speed power slide mechanic, went overlooked and underappreciated. Still, it grew in popularity over the years as a cult classic, slowly finding an audience that missed it upon release.

With the trend of porting more Japanese console games to computers, PlatinumGames and Sega released Vanquish through Steam in 2017. This allows for a number of substantial improvements – perhaps most importantly, higher frame rates (the console versions, roughly identical, are capped at 30 FPS), which gives the intensity of the power slide an extra bit of punch. It also has higher resolution and fancier visuals, and most important, mouse control. Given the speed and precision that the game asks, Vanquish, like many first person shooters, ultimately it feels much more at home with this method.

Vanquish still holds an important place in the recent history of video games. It offers a preview of how later Platinum titles would look, but its importance stretches beyond that. Its scoring system foreshadows the newly revived interest in arcade-esque game design, as seen in Inti Creates’ recent output. In addition, its juxtaposition alongside American shooters foreshadows other Japanese games that took influence from popular Western design trends, like the open worlds of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain and Final Fantasy XV. If Vanquish has left its mark on history, then it’s a subtle yet significant mark.