- Vectorman

- Vectorman 2

“WINNERS DON’T USE DRUGS” is probably one of the most iconic political slogans of all time, with most – if not all – arcade cabinets produced during the last ten years of the 20th century spreading a unique fraction of USA President Bill Clinton’s war against drugs all over the world. “RECYCLE IT, DON’T TRASH IT!”, which was introduced in game centers nationwide half a decade after Williams S. Sessions’ ever-popular catchphrase hit the market, is not as fondly remembered, but its message stays true up to this day, with both global warming and pollution levels still increasing at an alarming rate and bringing a swathe of other problems alongside them. The manufacturing of video games and other electronic devices is partly to blame for all of this, but this didn’t stop the former from joining the pro-green ride of the mid-to-late 90s at the same time the race for 16-bit supremacy was coming to a digitized end. Sega of America was one of the first big-name game developers to cash in to such circumstances, and the result of their collaboration with BlueSky Studios – who had previously worked on the Genesis Jurassic Park games – was Vectorman, an action-platformer that is not only a worthy competitor to Nintendo’s Donkey Kong Country trilogy, but also a game that perfectly encapsulates what 90s Sega was all about.

Vectorman‘s plot may be familiar for anyone who watched Pixar’s 2008 movie Wall-E: after centuries of environmental degradation and pollution, mankind has fled to the stars, leaving Earth in the hands of the Orbots – highly-intelligent, self-maintaining robots who, despite their shape-shifting abilities and heavy armaments, work almost exclusively on menial tasks – for a major clean-up operation, one that was going smoothly until an abandoned nuclear warhead was accidentally plugged into the Orbot leader Raster’s control unit, filling not only his, but all of his kind’s programming with a mad desire for death and destruction. Now known as WarHead, the Orbot hive-mind declares war against the incoming humans, with Vectorman – a sludge barge-piloting Orbot who was busy doing his job in outer space when his brothers’ minds fell under the mechanical warmonger’s control – now being the only hope for the planet and its original inhabitants, who are already on their way home after decades of space travel.

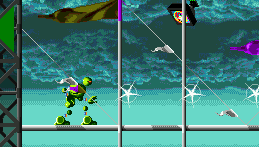

Unlike in Super Mario Sunshine and the Oddworld franchise, Vectorman‘s environmental message has no ties to the title’s gameplay, which combines both Western and Eastern game design philosophies into an interesting hybrid of Donkey Kong Country, Mega Man and Turrican with a few quirks of its own. Right from the start, Vectorman is equipped with a long-distance peashooter and a kickass double jump which also doubles (pun intended) as a powerful offensive technique if timed just right, with powerups being acquired either as rewards for defeating enemies or by destroying the floating televisions which are scattered through the game’s 17 stages. Pickups here are divided into four “classes”: health orbs, which can either heal you in various increments or expand your life bar by a point for the duration of the game; weapons, of which the most iconic is the oddly-named “Bolo Gun”, an extremely powerful (and rare) spinning shot which can hit multiple enemies several times if timed right; Morphs, the game’s most obviously Donkey Kong Country-inspired element besides the digitized graphics; and finally, Multipliers, usually useless leftovers of the arcade era that prove themselves to be the player’s best friend in Vectorman, since they have an effect not only on the score (which awards extra lives on certain thresholds), but also on extra life pickups, which means that, with enough patience and exploration, a skilled player can get up to ten extra lives with a single pickup. If Vectorman‘s huge amount of items to pick up boggles your mind, don’t worry: the good guys at BlueSky Studios thankfully included a handy item guide in the game’s options menu, something that may be common nowadays, but was practically unheard of back when it was released.

While Vectorman owes its graphical style to Donkey Kong Country and most of its gameplay to the run-n-guns of its time, its level design is clearly influenced by Rainbow Arts/Factor 5’s Turrican franchise. Much like in the first two installments of Manfred Trenz’s classic euro-platformer series, the game’s stages are huge, non-linear and filled to the brim with secret passages and invisible platforms, with exploration being limited only by the player’s memorization of enemy and item placement and the strict time limit that comes along for the ride. However, Vectorman‘s level design is not only one of its biggest strengths, but also its greatest weakness, as enemy placement often feels sadistic due to the character sprites’ large size and the free-form-scrolling nature of most stages. This, combined with the fact that most enemies take a lot of punishment and the occasional leap of faith, makes the game have a slow, methodical gameplay style that is unique to it and may take a while to get used to, again, much like in Turrican.

What Vectorman lacks in consistent difficulty and compact level design, it more than makes up for in its presentation, which is where all of BlueSky Studios’ offerings shine the brightest. Proclaiming that the SNES is graphically superior to the Genesis may be a tired cliché nowadays, but it’s an undeniable fact that most titles of the time looked better on Nintendo’s 16-bit console than they did on the competition and that Donkey Kong Country deserves praise for stuffing all of its then-high-tech graphics and timeless soundtrack in a single 32-meg cartridge with no special chips inside despite its bland gameplay (which the sequels greatly improved upon). In comparison, Sega’s console had a much paltrier VDP/PPU and less access to large ROM sizes, but its lightning-fast and easy-to-program-for Motorola 68000 processor could easily trump Nintendo’s choice of CPU (the unique, yet terribly slow Ricoh 5A22) in every aspect imaginable if in the hands of a talented programmer, and this is what makes Vectorman‘s unique graphical style look good up to this day. The game’s title may be a bit misleading, since there are no vector graphics to be seen here (unlike Ranger-X, which uses them in its boss debriefing/intermission cutscenes), but Vectorman‘s visuals are impressive anyway due to the character sprites’ large size and silky-smooth animation, which is achieved thanks to Treasure-esque multi-jointing techniques (this is best seen in most bosses’ death animations, where their individual sprites swirl around Vectorman and explode one-by-one as your final score gets tallied up, and in the main character’s morphing and death animations), some very effective parallax scrolling and ingenious use of the Genesis’ unique shadow/highlight routines, which provides not only fantastic lighting effects, but also effectively triples the console’s infamously limited color palette on certain occasions. Kickass graphical trickery aside, the game’s stages also ooze with creative charm, with the player traversing through the bright arctic ridges, desolate ruins and dark, maze-like structures of a clearly interconnected pseudo-futuristic world.

The soundtrack, composed by San Francisco musician/producer/small-time filmmaker Jon Holland, is an incredibly catchy showcase of Sega of America/Technopop’s infamous GEMS Sound Driver’s capabilities, being mostly comprised of low-key techno tunes that fit the game’s slow-paced gameplay for the most part but that sadly grows repetitive by the time players reach the final boss. Jon himself also worked on the high-quality arrangements of the game’s soundtrack included on the Sega Tunes: Vectorman CD, which was released one year later and, strangely enough, used the sequel’s boxart for its cover artwork.

All in all, Vectorman is one of the Genesis’ best hidden gems, a great platformer that, while having a few faults of its own, manages to aurally out-do Donkey Kong Country in almost every way while staying unique and memorable up to this day, with the title’s commercial and critical success (and eventual re-release under the budget Mega Hits label) gracefully backing up such claims.

Vectorman was originally released exclusively in North America and Europe, with its Japanese debut coming five years later on the Sega Archives From U.S.A. (A.K.A. Sega Smash Pack) compilation for Windows PCs, which was the first of many to include the game as a bonus treat among other, better-known Genesis titles. Some of the compilations which feature this title are the Sega Genesis Collection for the PS2 and PSP and its seventh-gen upgrade, Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection / Sega Mega Drive Ultimate Collection, and the GameCube/PS2 Sonic Gems Collection, which also marks the first time its sequel was released outside of the US. It is also sold separately on Steam and the Wii Virtual Console, as par for the course for most Genesis titles nowadays.