Video Game Book Reviews

Dungeons and Dreamers is another book that doesn't quite follow up on its title - actually, the fact that it doesn't include the name Richard Garriott alone is enough to constitute false advertisement. A good portion of the book is basically the Ultima inventor's biography. It begins with his school days and first contacts with both home computers and Dungeons & Dragons and first follows his career up to the foundation of Origin. A few anecdotes about other developers are thrown in for good measure, followed by a whole chapter on id and the Doom story. (Did you know Wolfenstein 3D was an Ultima Underworld clone? No, seriously, the book dramatically says about an early tech demo by the team that would eventually make Ultima Underworld: "Romero saw it, too.") Mostly to lead into the development of the LAN culture and online gaming, to set the stage for Garriott's Ultima Online as the revolution in gaming.

Then all of a sudden we are faced with a chapter focusing on the Columbine incident and the following shitstorm against violent video games, which is one of the more differenciated narratives on the matter, but by this point feels really tacked on regardless.

It's interesting to read some quotes by MIT professor Henry Jenkins, author of the book "From Barbie to Mortal Kombat" and participant in the hearings after Columbine, especially since his theories deal with video games from an old-fashioned but at the same time rather insightful viewpoint:

Exploration of the environment has long been a critical part of growing up, particularly for boys, and video games have become that space for urban children without access to forests and fields.

As the boys play these macho games, their parents - and particularly mothers - are suddenly exposed to the content of adolescent fantasies that traditionally have been kept well outside parental view.

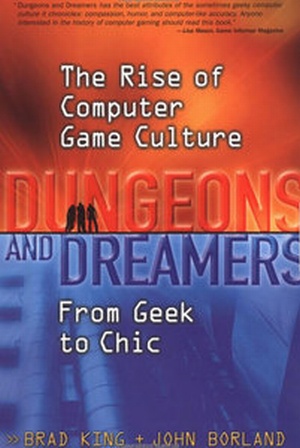

It just doesn't gain the weight it deserves in a book where the last sentence of every third paragraph opens with "Just as Richard's..." or "Like Ultima..." Who's the father of video games? Bushnell? Baer? Russell? In the eyes of Brad King and John Borland, apparently it's Garriott.

The authors are also never quite explicit about this supposed transition "from geek to chic," or what this "chic" is supposed to mean in this context, for that matter. Sure, there is some babble about changing demographics of the people that play video games, but even the book itself concludes towards the end: "It's still a little geeky." The kind of games that Richard Garriott used to make still is, eight years later.

All that said, if you cut away some of the fat (and use it for books that concentrate on other subjects) it is a very good biography. At times it feels as if Garriott's voice is felt even more clearly than the authors', and that's the way it ought to be in a biography. The language can be somewhat pompous, with plenty of superlatives and more 4-syllable adjectives than you can shake a stick at, but there's also the humble moments of sincere awe, when Garriott talks about how his do-gooding Lord British was schooled about the ethics of his creation by a petty thief, or about players that seized "his" castle in Brittania during a demonstration against bad lag: "As unhappy they were about the game, they voiced their unhappiness in the context of the game."

It couldn't have come at a better time, too. In its concluding chapter, Garriott is just working on Tabula Rasa in its early stages, his last big game project and the one whose failure marked at least a temporal halt in his exceptional career as a game designer. Nonetheless, the authors were working on a new edition as of summer 2011, but the project blog hasn't been updated in a while. The first chapters are also available for download as an audio book, although it is not a professional read and at times not that pleasant to listen to.