Video Game Book Reviews

The great Ralph Baer, inventor of video game consoles, passed away recently, so it's high time to take a look at his memoir of the events that led to and followed this innovation that would so greatly change the world of home entertainment.

Ralph Baer is often fondly referred to as the "father of video games", but in less favorable eyes he is also remembered for fiercely defending his patents and a perceived bitterness towards Nolan Bushnell's long-time "usurpation" of that title. And that image is confirmed in the book's first chapter, which seeks to establish who really invented video games, and it's mostly an unabashed lashing out against Bushnell and the gaming industry's early history keeping faults that had exiled Baer's name to "further mentions" for so long. In Bushnell's case it might be all deserved, but it seems a bit petty and also a bit sad when he starts attacking the other fathers of video games. This applies mostly for Stephen Russell, whose seminal creation Spacewar! he dismisses mostly on the grounds of Russell not having called dibs in the form of patents and the lack of mass market ambitions: "To put a finer point on it, both "what-ifs" and even real inventions are a dime a dozen and not worth more unless they lead to practical results in the real world and stand up in court, if it comes to that." Disregarding on the fact that Spacewar! gave rise to the university game programming culture, which resulted in most of the more complex genres we know today. Then he gets stuck up in an awfully technical, outdated definition of video games, which is limited to a specific method to display games on a CRT TV set via a peripheral. By that account, video games apparently died with the spread of HD TVs, while arcade and computer games never truly were video games to begin with.

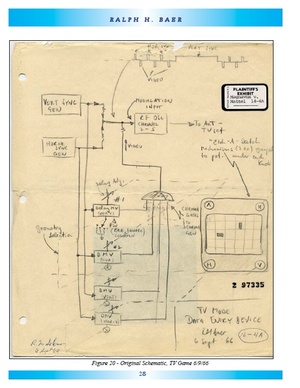

Troubled entrance put aside, Baer's clinging to technicalities is what makes the rest of the book so phenomenal and special. His accounts are so precise and detailed that it might seem incredible that anyone's memory would be so impeccable after all these years. But when it comes to the hard facts, you never have to take his word for it, because he has kept all his documents close and in order, and the whole book is teeming with scans and photos. When Baer describes how he first kicked around ideas for TV game concepts with his subordinates as an unofficial side project at Sanders, the defense contractor he was employed at, you not only get to see his original hand-written notes, but also the official company document he made his secretary type in, and even the diagrams for the circuitry. The narrating part of the book even ends after 170 pages, and beyond that it's all schematics and patents and detailed timelines (with the respective sources listed!) and photos upon photos of TV game devices and other inventions. It really is such a remarkable and unique document, the video game medium can consider itself lucky to have such a thorough bookkeeper among its pioneers, and it should be held up as an example in an industry where companies often frivolously discard meaningful documents and loose source codes.

This also means, however, that Videogames: In the Beginning often reads more like a dry historical chronicle compared to the sweeping storytelling and human drama that makes it so hard to put away David Sheff's Game Over or the many interesting big print quotes that pull you from paragraph to paragraph in Steven Kent's The Ultimate History of Video Games. Especially for those not versed in electronics, it might be a bit of a chewy read at times. For anyone who actually wants to know how game consoles came into being, and not just when, where and by whom, the book is a treasure.

Some of the most interesting parts of the account aren't necessarily those aspects that were eventually turned into Magnavox' Odyssey console, but the many inventive game concepts, peripherals and features that didn't make the cut, or the plans to team up with cable firms to deliver games with life-like TV backgrounds. Although Baer wants no misunderstanding about the fact that he was the inventor of video games, he never forgets to give credit to his colleagues where it is due, mostly Bill Harrison for developing much of the actual circuitry and Bill Rusch, who was brought on board as a game designer when the project needed a killer app, and came up with the ping pong game that would have such a bright future in other people's hands. The book also goes beyond The Beginning to delve into not as often retold episodes in Baer's career, like his contributions in getting Coleco's video game operation off the ground, and also of course the patent litigations he got involved in during the decades to come.

While In the Beginning may not always be the most engagingly written book on video game history, it is certainly among the most important, and it convinces through its incredible content rather than extravagant prose. Whether or not you subscribe to the narrative that paints Ralph Baer as the ultimate, undisputable founding father of video games (the publisher was wise enough to credit him as "The Inventor of Home Videogames" on the cover), there is no doubt that he was one of the most important of several fathers In the Beginning, and that makes him more than worthy of more celebration than he has been getting for much of his lifetime.