It’s hard to imagine video gaming without Fallout, but it’s even harder to imagine Fallout without the original open world, post-apocalyptic game that allowed you to smack children around with crowbars, exterminate entire bloodlines, only to become big damn heroes saving the world from a robotic menace considering humanity to be well past its expiration date.

Origins

Back in 1986, Brian Fargo’s Interplay struck gold with Tales of the Unknown: Vol. I – The Bard’s Tale, a first person dungeon crawler that built on the ideas pioneered by Sir-Tech’s Wizardry series. While the game was followed by two sequels, subtitled The Destiny Knight and Thief of Fate, the success allowed Fargo to try something new. Together with veteran tabletop RPG designers Ken St. Andre, Michael Stackpole, Dan Carver, and Liz Danforth, he set out to create an adventure that traded swords for guns, sorcery for chainsaws, and high fantasy for the post-apocalypse.

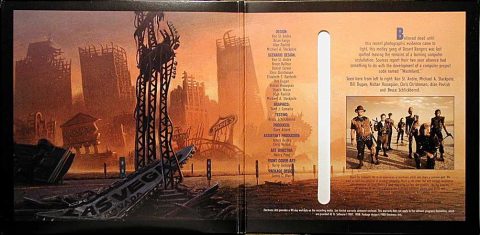

Developed over the course of the next two years, Wasteland drew on the nuclear scare of what turned out to be the terminal decade of the Cold War, freely mixing in elements from apocalyptic fiction the creators loved, such as Planet of the Apes (1968 through 1973), the Mad Max series (1979, 1981, and 1985), The Terminator (1984), and Red Dawn (1984). In fact, Fargo originally wanted to create a story modelled after Red Dawn, with players stepping into the shoes of American guerrillas fighting against the Soviet occupation. St. Andre convinced him to pursue a different idea, pitting the remnants of humanity in a desperate fight against a robotic menace, in the desolate post-nuclear deserts in what was once California, Nevada, and Arizona.

Wasteland became The Terminator instead of Red Dawn, set a hundred years after the nuclear holocaust nearly wiped humanity out in 1998.

Story

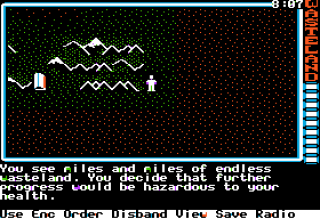

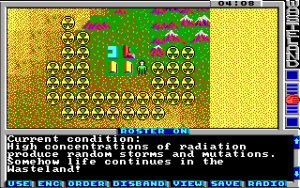

The nuclear exchange between the superpowers toppled human civilization, turning humans from apex predators into endangered species that has learned little from the collapse. Isolated pockets of humanity survive, separated by blasted sands, intolerable heat, and the occasional mutated horror. You step into the shoes of a survivalist group descended from a battalion of Army Engineers, stranded after the Big One deep within the deserts of the American Southwest.

The engineers seized a newly constructed federal maximum security prison, banishing the death row inmates into the surrounding wasteland, and then inviting the surrounding survivalist communities to join them in their efforts at building a new society. The community withstood the test of time and sieges by desperate inmates trying to retake the prison. When the denizens of the prison learned that other towns also survived the holocaust, they decided to aid others in rebuilding civilization, styling themselves the Desert Rangers, in the tradition of Texas and Arizona Rangers of the early 20th century.

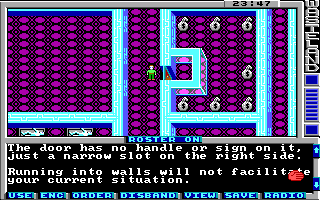

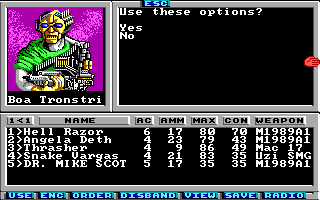

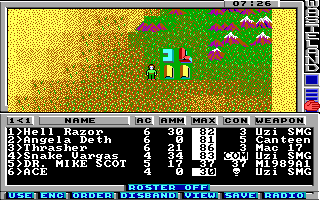

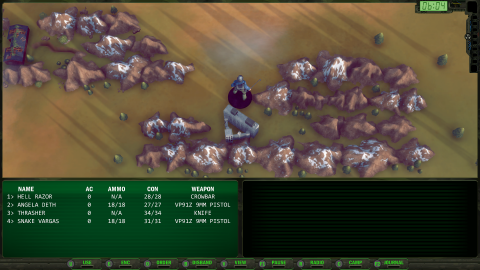

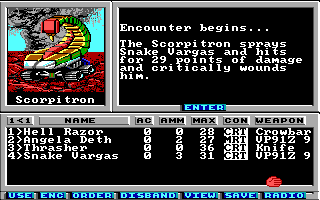

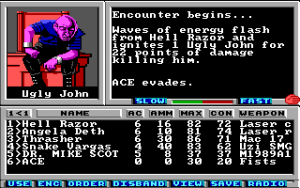

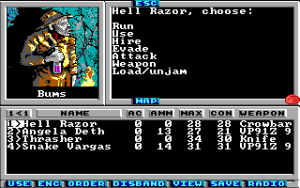

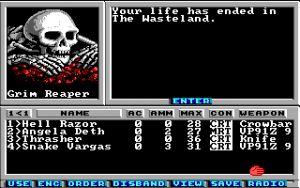

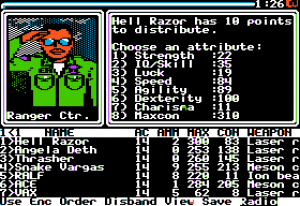

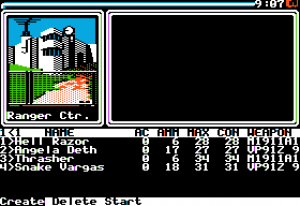

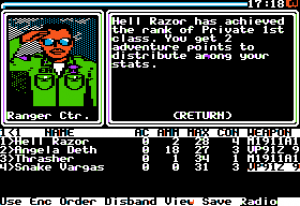

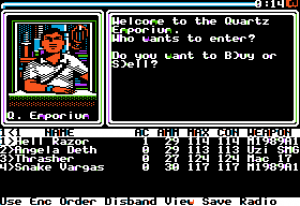

A century after the war, your newly formed team of Rangers (Hell Razor, Angela Deth, Thrasher, and Snake Vargas, although you can freely create your own team) is sent out from the Ranger Center on a mission to investigate a series of disturbances in the desert. You’re handed your pistols, ammunition, and full canteens, and sent out of the gates.

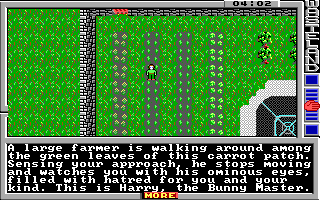

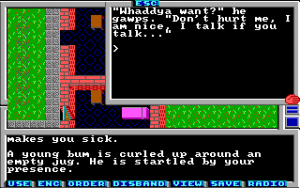

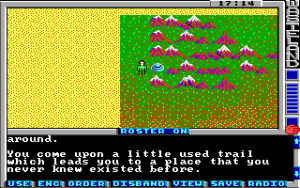

You can start by visiting Highpool, the agricultural center, and the Rail Nomads camp. These early game locations serve to gently ease you into the game’s persistent world and provide a few easy problems to solve: Fixing the water purifier at Camp Highpool and dealing with a rabid dog hidden away by a local youth, saving farmers from a vermin plague orchestrated by a disgruntled Bunny Master, and delivering a Visa card to a Rail Nomad who settled down in a Quartz to the west, beyond the mountains.

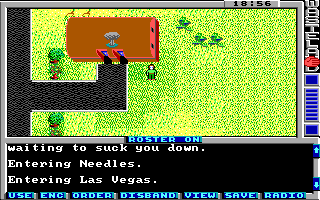

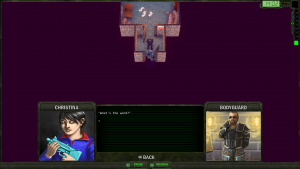

Upon arrival, you realize that it’s been attacked by a band of desert raider, who have taken hostages and terrorize the populace. If you decide to help, you eventually save a mechanic from Las Vegas. The mechanic can fix up the broken-down jeep south of town, bringing you to Needles, a town still bearing the scars of the Sino-Soviet invasion after the nuclear war that fizzled out. After dealing with the town’s blood cult, you finally reach Vegas, the jewel of the desert, under siege by a mysterious robotic menace. Navigating the city’s factions and sewers you learn of the true nature of your enemy and gain access to long-lost military bases, rife with wondrous technologies, dark secrets, and mad plans for remaking the world. Then you save the world.

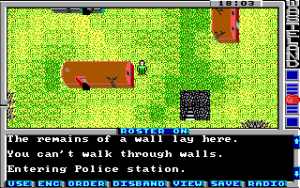

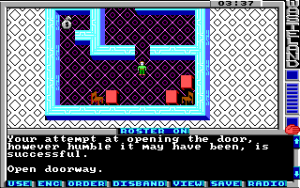

However, that is only one path through the game. There’s nothing stopping you from making a beeline for Vegas to pick up one of the strongest recruits in the game, to Needles to stock up on automatic weapons that turn the first half of the game from a challenge into a turkey shoot, or just blazing a path of destruction across the wastes. A door stands in your way? Blast it open with a rocket. Don’t like the Mushroom Cloud cultists? Start shooting.

Highpool’s children annoy you with their jeers after you slip and fall into the water one too many times?

Wasteland doesn’t judge.

Mechanics and gameplay

Wasteland gave players the freedom to explore the world at their leisure, combining it with a free-form character creation and development system. Based on Michael Stackpole’s Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes ruleset, itself an evolution of the Trolls & Tunnels tabletop pen-and-paper game by Ken St. Andre. Both were designed to be easy to use and fun to play, rather than provide mechanical complexity.

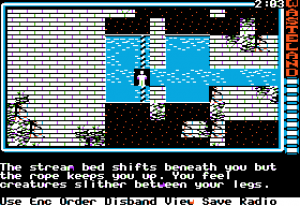

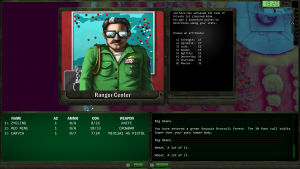

Each of your characters defining characters through seven attributes (Strength, IQ, Luck, Speed, Agility, and Dexterity) tied to 35 skills, ranging from climbing and swimming, through weapon mastery, to piloting attack helicopters and toaster repair. Not all of the skills have equal utility and a significant number has only marginal uses – but on the flip side, there are only a handful of must-have skills – such as Picklock, Assault Rifle, Energy Weapons, or Perception – and there is enough experience in the course of normal gameplay to make any mistakes forgiving. All skills increase in level through use, either active or passive, as long as the character has at least one level in them.

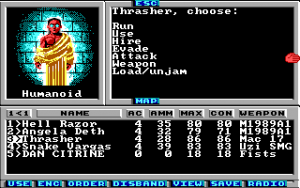

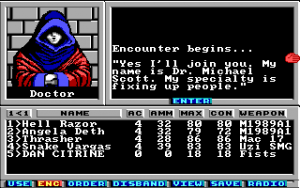

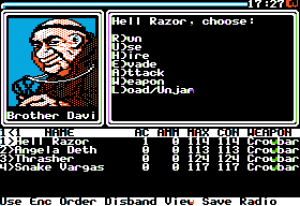

You can control up to four Rangers created at the Ranger Center at any given time. The full squad can count seven members. The slack is picked up by the game’s 14 recruitable characters, who are functionally identical to Rangers, except for a chance to disobey orders and no control over their trigger happiness in combat.

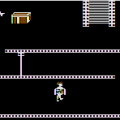

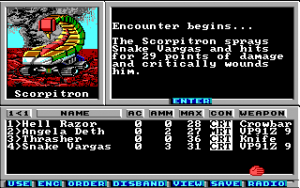

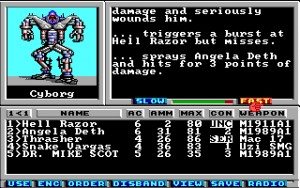

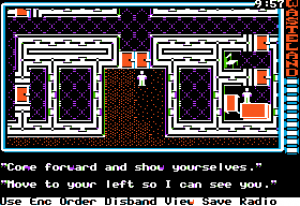

Speaking of combat: The system is heavily abstracted, emphasizing ease of use and speed, rather than tactical complexity. The turn-based system doesn’t feature formations (unlike e.g. Might & Magic, where the order of the party matters) and actions are executed sequentially according to the Speed attribute of the participants. This fundamental simplicity allows for participating in some spectacular (and tense) battles against dozens of enemies.

The absence of magic is compensated by emphasis on weapon properties. Explosives can be used to damage all targets in a map square. Automatic and energy weapons can be fired in bursts or by emptying the entire magazine against a group of targets. Finally, melee weapons gain additional attacks per turn as the fighter’s skill increases and yield double experience (even improvised weapons; any item can be equipped and used in melee).

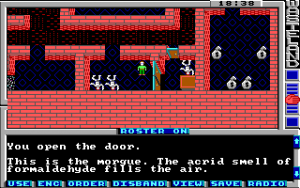

Finally, your characters can be wounded by enemies, who can use the same tricks against your party. A party member in serious, critical, mortal, or comatose condition needs medical attention, either from one of his fellow Rangers or followers, or a hospital. Some of the most tense experiences come when you have no conscious medic in your team and have to double back to the nearest infirmary.

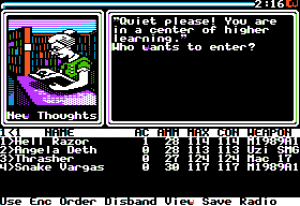

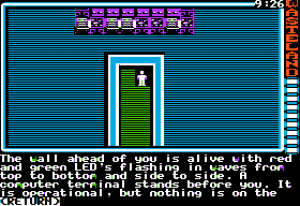

This is the biggest strength of Wasteland: These tense moments draw you into the world, jogging your imagination and helping you fill in the blanks in a story that would otherwise be a loose jigsaw puzzle. As your plucky band of Rangers, survives in the wasteland, figuring out its mysteries and challenges, you don’t sit through cutscenes or endless dialogues, but participate directly in it and create your own story. The sole exception to the rule are paragraphs, a clever solution to limit the size of the game and get around space limitations: These fictional vignettes were a separate book in the original release, and provided colourful vignettes to enrich the world and provide crucial passwords and information needed to advance the story. It also doubled as a form of copy protection.

Summary

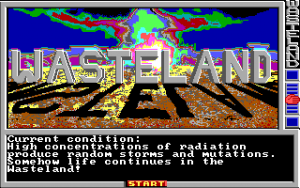

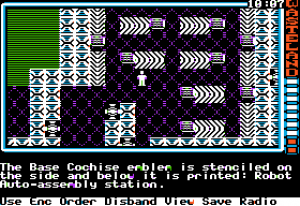

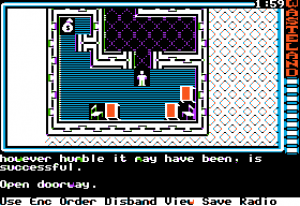

Wasteland was an impressive game in its time: It offered an overhead, Ultima-style navigation with an expansive, persistent world with unique locations, an actual plot, and a detailed setting – all with decent graphics and animated encounter portraits to boot. At the same time, it managed to fit on just one 3.5’’ floppy disk (or two double-sided 5.25’’ in the original release) and a paragraph book.

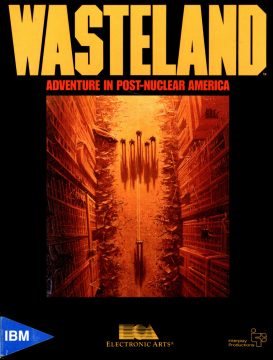

When it was released in 1988 it became the Skyrim of its time: A runaway hit for Apple II, Commodore 64, and DOS, selling a quarter of a million copies, earning acclaim from gamers and reviewers alike, and a very profitable product for Electronic Arts.

That’s when it became a victim of its own success.

FOUNTAIN OF DREAMS

In the Meantime

Interplay would attempt to create its own follow-ups to Wasteland. Its first attempt was Meantime, a time-hopping RPG in its image. You’d step into the shoes of time travellers battling a group of villains trying to warp history by altering past events. Your party would travel across time in hot pursuit, picking up various historical figures to aid them in their quest. Planned companions included Amelia Earhart, Cyrano de Bergerac, Albert Einstein, and even Wernher von Braun. Each would bring a unique set of skills to the table.

A similar gimmick was included in Escape from Hell. However, unlike that game, Meantime never saw the light of day, becoming a casualty of the changing industry landscape. Built on the Wasteland engine, it was built primarily for the Apple II and Commodore 64. However, their decline coupled with the departure of Liz Danforth, one of the principal writers on Wasteland, resulted in Fargo deciding to cancel the game.

It was briefly revived in 1992, with the intention of porting it to DOS. Bill Dugan, one of Wasteland’s developers, headed the effort. He also decided to scrap the project after the antiquated code proved to be too difficult to update – three years might as well have been an aeon – and the static graphic couldn’t compete with the likes of Ultima VII – Black Gate.

It would take several more years for Interplay to make another attempt to follow up on Wasteland. After securing the GURPS license from Steve Jackson’s Games, a small group of developers within Interplay set to work on producing a game out of it. Led by Tim Cain, they set out to create a game based on GURPS mechanics and eventually settled on a post-nuclear setting. As long time fans, they naturally wanted to create a sequel to Wasteland. Their enthusiasm was dashed after the legal department informed them that Electronic Arts still held rights to the Wasteland property.

They couldn’t make a sequel, so instead they made Fallout, with a proud tag line on the box asking buyers if they remembered Wasteland. They did: Fallout became a sleeper hit and was catapulted from a B game that executives didn’t think about too hard into a flagship title.

Fallout would suffer a similar fate as Wasteland, though this time at the hands of its own. Increased interference from management and marketing would drive Tim Cain and other original developers from the project, while the frenetic development pace of less than a year would make Fallout 2 legendary for its bugs. The franchise would also be exploited by its publisher to generate income with ever poorer quality titles, before being sold to Bethesda Softworks.

Wasteland would have to wait for a total of 26 years to receive a proper sequel, setting a Guinness World Record and blazing new trails.

http://www.artfulgamer.com/electronic-arts-the-destroyer-of-worlds-sets-its-eye-on-bioware/

Wasteland re-editions

An interesting aspect of the series is the sheer number of re-releases of the original. It has been released for three separate platforms – Commodore 64, Apple II, and IBM PC – and later re-released two times over, for a total of five editions. What distinguishes it from other games is that it’s all the same game, including the 2020 Remastered version.

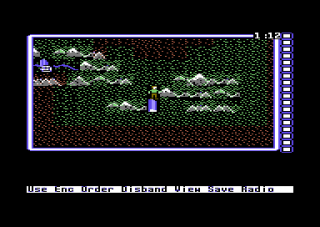

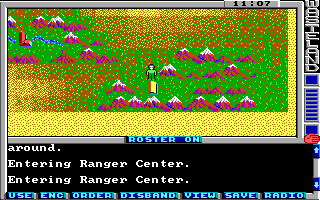

The differences between the initial three versions boil down to visuals, as the fundamental gameplay remains the same. The PC version is the most commonly circulated and formed the basis of the re-releases, the Apple II and C64 versions are notable in their own right: While the graphics are much less detailed, they do feature smoother portrait animations and a fully animated intro with simple sound effects that shows the nuclear war as it happens, complete with the destruction of the Citadel Star Station.

Ultimately, the PC version with its more detailed graphics, performance, and the ability to record macros and assigning them to function keys, would become the definitive Wasteland version for over two decades, until inXile finally secured the right to release the original game from Electronic Arts.

The Original Classic was promised as a backer reward during Wasteland 2’s Kickstarter campaign and was released in November 2013. It runs the original version through a custom emulator, featuring several quality of life improvements, such as integrating paragraphs into the game itself (along with a voice-over), option to use upscaled graphics, a soundtrack by Edwin Montgomery, and – for the first time – actual save games, meaning you didn’t run the risk of overwriting your master disks and losing the game.

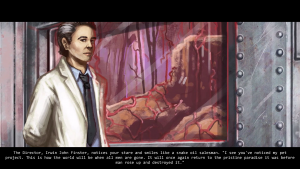

The Remastered version is primarily a graphics upgrade and interface overhaul. At its core, it’s exactly the same game, rebuilt in Unity using as much of the original as possible, paired with Wasteland 2 graphics and some essential features, like saving the game at any point and cutscenes for what was originally a paragraph. It’s an interesting choice, in line with what modern remasters have offered (such as Starcraft or Command & Conquer), but the use of new and improved also highlights the fact that the original open world game was far more than merely the sum of its parts.

The original Wasteland heavily relied on your imagination and engagement. The graphical and quality of life upgrades seemingly add to the game, but also make it a lot more literal. There are far fewer blanks to fill and the resulting game feels a lot more dated than the original.

In a way, it shows that less is frequently more – and in this case, tremendously more, to the point that the original, whether played on Apple II or through any of the DOS emulators, can feel so much more immersive at times. That is in spite of the fact that the Remastered version now features proper quest tracking, cutscenes, and even variable endings.