Wild Arms XF (“Crossfire”) is a competent and interesting strategy RPG. Though it’s the first non-turn-based entry, the jump to SRPG could have been anticipated by the light SRPG elements in the last two games. XF contains all the hallmarks of its genre with a fair share of unique quirks, some of which serve in its favor and some of which get in its way.

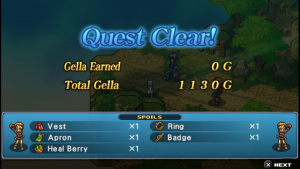

XF‘s place in the Wild Arms canon is undeniable in some ways: You get basic things like heal berries, Gella, and revive fruit, plus more all-encompassing things like Guardians, a Filgaia once again on the verge of ecological collapse, and villains striving to wield technologically advanced weaponry. Its soundtrack even has a few songs lifted near-directly from the classic games. Despite all that, though, its connection to the rest of the series feels tangential. Sort of surface level. It’s a fantasy game with a few Wild West looking settings, not a fantasy/Wild West/sci-fi/steampunk/desertpunk mishmash as every other game has been. Not a bad thing in itself, but a weird way for the series to peter out, with a game that doesn’t even have the feel of its predecessors.

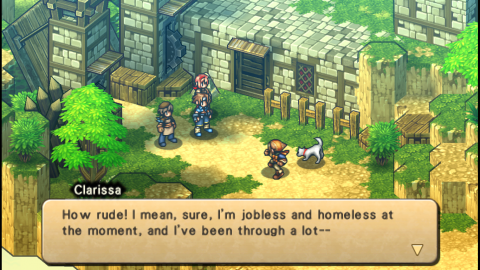

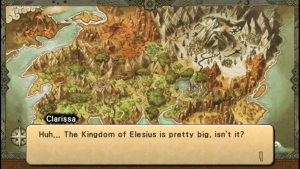

The plot is convoluted in a way that only strategy RPGs seem to be able to pull off. Essentially, you place Clarissa Arwin, a girl who travels to the kingdom of Elesius with her adopted brother Felius to retrieve her mother’s sword from a ruthless drifter, Rupert. What could have been a straightforward MacGuffin hunt becomes instead a dense and complicated political conflict. That’s because upon arriving in Elesius it’s revealed that Clarissa is a dead ringer for the purportedly dead princess Alexia. One thing leads to another as she adopts Alexia’s identity and becomes the leader of a movement to overthrow the kingdom from its current rulers, the corrupt Council of Elder Statesmen.

The group she forms is called Chevalet Blanc. The main protagonists are Clarissa and Felius; a magician named Labyrinthia Wordsworth who was Alexia’s personal tutor; a young boy and heir to the noble House Brenton named Levin Brenton; a mercenary who wishes to destroy Elesius for its crimes against humanity named Ragnar Blitz Lebrett; and Labyrinthia’s companion animal Tony, a white dog. There are several other NPCs crucial to the plot, as well as other spoiler-y companions who join along the way, but these are the core protagonists. Like many other SRPGs you can also recruit generic mercenaries to fight alongside you in battle.

Just as the plot seems overly complicated, the gameplay can also be daunting to a first-time player. The systems are actually fairly intuitive once you get a feel for them, but they can be confusing to start.

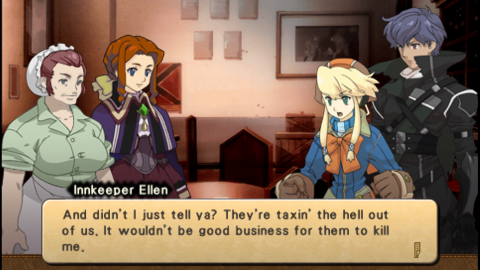

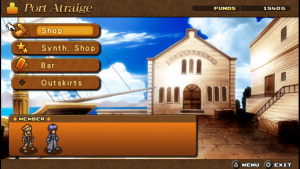

The majority of time in non-combat scenarios in XF is taken up by navigating menus. Some of it is fun, but there’s a lot of micro-management involved. Nothing as bad as, say, most Idea Factory games, but bad enough.

Perhaps the largest system is the class system. There are many different classes to choose from, most of which aren’t the familiar Black Mage, White Mage, Monk, Chemist, etc. There are comparable classes, but many are oriented in terms of stats and tricks rather than defensive versus offensive. “Sacred Slayers”, for example, are important because they have good defense against magic spells and have the ability to cast spells on several hexes at once. The main protagonists also have their own unique classes. Clarissa is a “Dandelion Shot”, which is a specialization in firearms, while Labrynthia is an “Arcanist”, a specialized version of the Black Mage-like Elementalist. You can mix and match class skills once you’re sufficiently advanced in a class, though, and most battles will require such hybridization to complete.

Further explanation of the class system has to run alongside an explanation of the battle system. As one might guess, the grid in XF is hex-based rather than squares. This means six different sides to be attacked from at any given time. There is no advantage or disadvantage to the direction a character is facing. The main component of the hex system that will affect players in any given generic battle are Formation Arts. If player characters surround an enemy in a number of combinations, like on opposite sides or three each a space apart, then they will deal a more powerful attack. Otherwise for the most part the grids play just like normal square ones. Elemental hexes are back too, but they can only be seen and effectively exploited if a character is in the Geomancer class.

Battles are more puzzle-oriented than a lot of other SRPGs. The stronger you get the easier it becomes to brute force your way through most encounters, but in the first chapter especially you’ll find yourself micro-managing classes till your eyes fall out.

A battle toward the end of the first chapter, for instance, requires you to defeat a large group of fast-moving enemies before they reach a certain point on the map. So you need classes that can move around a wide radius, that act quickly, and that deal enough damage for you to defeat the enemies in time. It is very difficult balancing all those parameters. Elementalists can deal the most damage if you exploit enemy elemental weaknesses, but they don’t move very fast. Geomancers have a “Lock Out” ability, which can help prevent enemy movement, but they aren’t very strong.

So you have to combine the powers of multiple classes. If you level up a class a certain amount of times, you can equip their skills and equipment without actually belonging to that class, so it becomes a matter of organizing a balanced team for the exact requirements of each mission. This can get really tedious, especially given that your characters automatically unequip all their items and equipment every time you switch classes. There is at least a “Favorites” option to automatically reequip your team, but these too take time to organize.

The thing is, leveling up classes takes time in random encounters. And your random encounters happen on many of the same battlefields that require this careful class orientation. You may find yourself stuck in a battle because you only have classes that can’t move past a certain roadblock, or with characters who can’t exploit the monster’s weakness. So you have to take time to reset the battle and reorganize your team. Battles in SRPGs already take a long time and this just adds to the total. Not to mention, the rewards for random battles aren’t that great.

There are other little systems, like item searching, that add little new dynamics to the mix. Item searches are when you send a group of generic characters out to any given battlefield and wait either by paying some money for each wait period or getting into fights a number of times, usually two. When they come back, they’ll have raw materials that you can take to a synth shop in town and use to make upgraded items. It can be fun seeing where the materials you need are and following each item down its upgrade path, but when you reduce the system to its core it’s mostly just busywork, a way to elongate the task of buying new equipment. Which, given the amount of characters you’ll need and the amount of classes with their own equipment specifications, you’ll be doing a lot of.

As Wild Arms is a series noted for its clever puzzles, it makes sense that XF would want to carry that tradition on. The problem is that combining the puzzles with the need to switch classes makes the game drag. It is extremely slow. More than that, there is a lot that feels like padding, like how only certain classes can destroy barriers and how most classes can’t use items on their allies. There is a way to make an SRPG puzzle-focused rather than combat-oriented, and perhaps XF should have leaned more heavily in that direction. As it stands it fails to keep the balance between combat and puzzles, making progress in the game much slower and less rewarding than it needs to be.

Michiko Naruke didn’t return to do the soundtrack. Instead we have her followers, contributing composers for WA4 and WA5 respectively Koda Masato and Noriyasu Agematsu. Junpei Fujita, Hitoshi Fujima and Daisuke Kikuta also contribute. The three along with Agematsu are part of Elements Garden, a “music production band” for video games, anime and other musical artists. The music is undeniably beautiful. Where the setting lacks Western vibes, the music rushes in as always with twangy guitar and whistling.

Released in the US in 2008, Wild Arms XF marks the first portable game in the series and the last internationally released proper title in the franchise. As mentioned in the WA5 article, there is a surprising darkness to the plot toward the end of the game, which shows itself in brief glimmers throughout the narrative. There’s an ARM, for example, that turns its wielder and all those around them into zombies, which causes some disturbing scenes. Darkness in a story isn’t of course the equivalent of depth or quality, but the underlying seriousness in Wild Arms games always seems to be handled well. They pack surprises one wouldn’t anticipate in an ordinary JRPG narrative.

In a genre that hosts the nuanced, layered, thoughtful narratives of Final Fantasy Tactics and Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together, Wild Arms XF‘s story manages to hold its own. Issues with the gameplay are that much more a shame, though, as they get in the way of appreciating the other things that make the game worth digging out your old PSP for.