“It’s exciting, feeling you’re on the ground level of something that is new… To me, it suggests so many different possibilities.” Mark Hamill, Behind The Scenes of Wing Commander III

Orchestral music swells as we are presented with the game’s title (accompanied by a tiger’s roar) and… actor credits!? Big names too, including Tom Wilson, Malcolm McDowell, and none other than Star Wars’s Mark Hamill as the star. Before long, a giant ship emerges from a jump point. With pointed, asymmetrical edges, it’s not unlike a giant mechanical claw, and it enters orbit over the homeworld of the Kilrathi Empire: Kilrah.

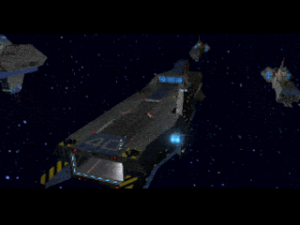

A Confed commando team has been captured in the Kilrathi capital, led by none other than your beloved Jeannette “Angel” Devereaux. Brought before Prince Thrakhath and the Kilrathi Emperor himself, she remains defiant. On the planet Vespus, Col. Christopher Blair (that’s you!), examines the wreck of the TCS Concordia alongside James “Paladin” Taggart. You have once more lost the carrier you called home, and there is no news of Angel’s whereabouts. Admiral Tolwyn reassigns you to the TCS Victory, an old rust bucket quite unlike the top-of-the-line Concordia. On the way over, a news broadcast states that despite Confed’s statements to the contrary, the war is going badly for humanity, with rumors of a plan for an emergency evacuation of Earth. But your assignment to the Victory will prove to be much more fateful than you initially thought…

Much had changed in the three years since Wing Commander II. The shift from 2D to 3D graphics was slowly picking up pace in the industry. While Wolfenstein 3D and its successor, DOOM, led the charge on PC (alongside Strike Commander), games like Daytona USA wowed arcade audiences. Even the Super Nintendo, which was starting to show its age, entered the fray with 1993’s Star Fox. Alongside this, both PCs and consoles were moving away from floppy disks and cartridges and towards the exciting CD-ROM format. The greater storage capacity afforded by CD-ROMs gave developers the opportunity to integrate pre-recorded cinematic sequences. Digitizing real actors had become quite the trend, after the unexpected smash hit Mortal Kombat, which dovetailed nicely with FMVs. And the same month Wing Commander III was released on PC, Japan saw the entrance of Sony into the video game market with its PlayStation, which would leverage said technologies into unprecedented commercial success and cultural impact.

“Chris Roberts comes up and says ‘hey, how about being in an interactive, CD-ROM, computer-sort-of-entertainment-style-game-film-experience?’ My first reaction, of course, was to say ‘What?’ ” Tom Wilson, Behind The Scenes of Wing Commander III

The road had been quite bumpy, however, for games built around full-motion video. In the early ‘80s, Dragon’s Lair caused a stir in video game arcades with its FMV animated sequences. The idea of an ‘interactive movie’ appealed to many, outpacing at the time the more primitive graphics from even the fanciest arcade games. Gameplay for FMV games was largely uninspired and lacked replayability, making them a curiosity at best.

It would take a few years for consumer-grade PCs and consoles to catch up. By the early ‘90s, more and more games with FMV sequences were released. The popularization of CD-ROMs made such games a possibility on both PC and consoles. Still, the popular perception of FMV games were that they were flashy novelties with cheap sets and stilted acting. Many such games sold well regardless, and some even garnered decent reviews. Chris Roberts and his expanded team pitched EA on an ambitious project that would use live-action sequences with Hollywood production values for the next Wing Commander. Roberts and his team felt the genre was still looking for a game that would exploit the potential of FMVs:

“Everyone talks about interactive movies, and multimedia and all the rest. But I think that no one’s done anything that defines it or makes a statement.” Chris Roberts

The game’s box did indeed bill it an ‘Origin Interactive Movie’, and the game received much greater publicity and attention than its predecessors. Electronic Arts’s strong marketing emphasized the Hollywood production values of the game’s full-motion video sequences, starring well-known actors. These included both sci-fi/fantasy and cult cinema performers like Tom Wilson (Back to the Future) and Malcolm McDowell (A Clockwork Orange, Caligula), as well as up-and-coming stars like François Chau (who would go on to appear in Lost and The Expanse). And the leading man? None other than Mark “Luke Skywalker” Hamill, fresh from his iconic role as the Joker in Batman: The Animated Series. They would star in a story that was pitched as the ‘end’ of the Wing Commander saga: a sweeping live action epic directed by none other than Chris Roberts himself.

Despite what the marketing may indicate, Wing 3 was still a space simulation game, iterating on the successful elements of its predecessors. Production was thus divided in two, with Chris Roberts directing the movie side of things in L.A., and Frank Savage leading the game development side back in Origin’s Austin office. Savage assembled a team which included several newcomers, all of them Wing Commander fans before joining Origin. Savage was a fan himself, famous for sporting a ‘WNGCMD 1’ Illinois license plate on his car.

The game presented a generational leap in terms of performance… and system requirements. At minimum, the game required a 486 processor, VGA graphics, and 2x CD-ROM drive. But its lush 3D textured models and FMV cutscenes meant it was clearly designed with Intel’s latest and greatest Pentium chip, as well as SVGA graphics, in mind. A joint advertising campaign with Intel yielded a poster, shipped with the game, which declared ‘Wing Commander III really flies on an Intel Pentium Processor!’

Meanwhile back in Texas, Origin Systems was undergoing changes of its own due to being acquired by Electronic Arts in 1992. While EA developed many games internally, the company’s success resulted in a time of expansion and acquisition of external studios. These studios would continue to create lucrative IP, but would now have access to greater budgets from their new parent company… along with added oversight.

Ballooning production costs and market pressures had landed Origin in financial trouble, which led to their acquisition by EA. Initially, reaction within Origin was positive: EA brought a bit of structure to the company, and a significant injection of cash. The staff at Origin doubled in size within the first year, with multiple concurrent projects to match. While this honeymoon was not to last, it allowed for the greenlighting of ambitious projects like Wing Commander III: Heart of the Tiger. The success of the series up to that point, and the development of Strike Commander as a tech base to work from, made EA excited for the game’s prospects. Electronic Arts was already building their own production unit, Crocodile Productions, to continue expanding into the growing market for games with digitized actors. Live-action capture in video games seemed to be the way of the future, and Origin was ready to explore this potential.

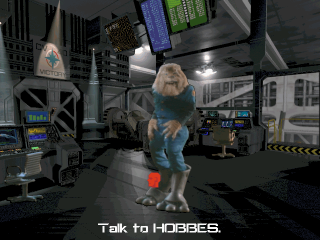

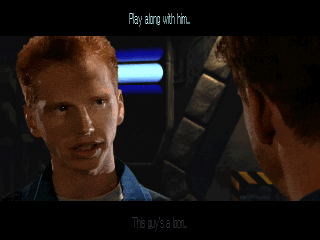

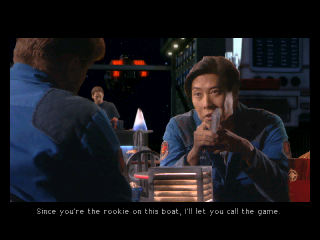

As you arrive on the TCS Victory, the big-picture view of the war falls away. You are confronted with a brand new cast to get to know, as well as a couple of familiar faces. Captain Eisen (Jason Bernard) greets you with some skepticism due to your war hero status, as the Victory is an old workhorse that isn’t exactly making headlines. Hobbes (John Schuck) and Maniac (Tom Wilson) return from prior instalments, and while your friendship with Hobbes remains strong, the rivalry and enmity between Blair and his academy buddy has only grown. The player can pursue a romance with perky chief tech officer Rachel Coriolis (Ginger Lynn Allen) or the determined pilot Flint (Jennifer MacDonald). Comms Officer Rollins (Courtney Gains) offers some comic relief laced with deep cynicism about the war effort. The cast is rounded out by several new pilots, each with their own backstories and attitudes: the idealist Vaquero (Julian Reyes), cynical card shark Vagabond (François Chau), arrogant test pilot Flash (Josh Lucas), and the traumatized, headstrong Cobra (B.J. Jefferson). You can develop your relationships with each pilot through dialogue choices in cutscenes, which will influence their morale and in a couple of cases, whether a pilot joins or leaves the duty roster.

The Confederation is losing the war. After a few deployments against the Kilrathi, Admiral Tolwyn (Malcolm McDowell) takes command of the Victory, so that it may protect Confed’s decisive weapon: the Behemoth. This unique starship is essentially an enormous laser, which can completely destroy a planet. Since Kilrathi society is heavily centered on their homeworld, destroying it could force a surrender. This endeavor is doomed to failure: In one of the most shocking twists in the series, Hobbes turns out to have been a sleeper agent all along. He has been leaking information to the Kilrathi, leading to the destruction of the Behemoth at the hands of Prince Thrakhath. The Crown Prince of Kilrah proceeds to taunt you by transmitting footage of Angel’s execution, leaving Blair devastated.

As losses continue to mount, both in the Confederation at large and aboard the Victory, the outlook is grim. But there’s still hope: Paladin (John Rhys-Davies) and his black ops team propose a risky operation to drop a ‘temblor bomb’ on Kilrah, which would exacerbate the existing instability in Kilrah’s tectonic plates to the point the planet would tear itself apart. Success in this final, daring operation is, of course, up to you.

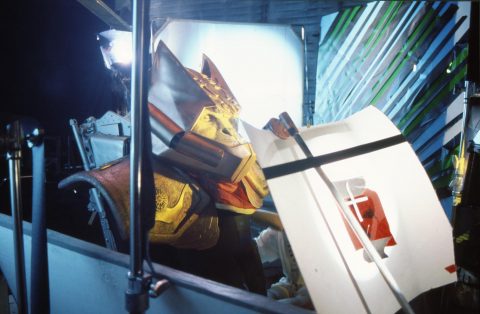

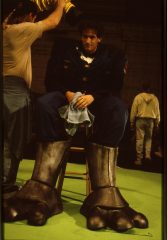

Chris Roberts had been working on a story outline while on breaks from Strike Commander’s punishing schedule, and now he found himself directing professional actors in a Hollywood setting. But it wasn’t a regular film shoot. While the actors would be shot on set with real Sony Betacam cameras, said sets didn’t physically exist for the most part. Instead, they would be added in through a technique known as chroma key, or green screen.

Chroma key involves making a small range of colors transparent so that other elements can be composited in, such as matte paintings or special effects like moving starfield. It was quite common in Sci-Fi and Fantasy productions, but the Wing 3 team innovated with the sheer extent of its use. With the exception of certain props, sets were made up of computer-generated images. These backgrounds were created back in Texas by Origin, and were then composited in real time during the film shoot with a system known as Ultimatte. After a take, actors could look at the Ultimatte machine’s monitor and see the CGI background already added into the scene. Such extensive use of chroma key caused several headaches for the crew, as the lighting for actors had to match the CGI backdrops. Any delay between backdrop creation in Texas and its safe arrival in L.A. meant the film crew did not know how the scene needed to be lit, necessitating reshoots once said backdrops arrived.

Malcolm McDowell observed, however, the sheer cost savings when compared to Star Trek: Generations, which was being shot at the same time:

“I have a feeling this is the way the movie business is going to go in the future, this may save [it]. They probably won’t do it all on green or blue screen. They’ll mix it with sets, and then the more expensive sets they can’t afford to do will be done this way, with computers. (…) I’m doing Star Trek at the moment, and they built the sets. What we see here on computer, they’ve built, and they’re up to 35 million dollars.” Malcolm McDowell, Behind The Scenes of Wing Commander III

The budget for Wing Commander III on the other hand, was around $4 million. While this is smaller than most games’ marketing budgets in the 2020s, at the time of its release this made it the most expensive game ever made. Its predecessor for that title had been Doom, with a much more humble $200k.

While actors sometimes struggled with the extensive use of chroma key, the true endurance test was the interactive side of things. Most scenes had several versions depending on player choice, which often caused confusion on set. Actors had to memorize the emotional state of their character at different points in the branching script, which would of course vary greatly depending on said branches.

Further complicating things was the way scenes were shot. Shooting scenes out of order is a standard practice in filmmaking, allowing for flexibility regarding scheduling and availability of cast, crew, locations, etcetera. For the actors, however, there was added complexity: shots were grouped per location, not per story choices, and could involve drastically different characterisation and emotion. As Jason Bernard put it, “[Y]ou can’t be as staunch one way, and then not be able to recover from that. […] But one moment when you’re playing one thing this way and then you come back and you play it another way, you just have to be very flexible. And you have to do your homework.”

The film side of the project necessitated an extensive crew, just like any regular feature. The first hire was Donna Burkons, who acted as producer of the film shoot. She wore many hats, acting as a liaison with the dev side in Texas, as well as getting the film crew together. Writers Frank DePalma and Terry Borst were tasked with turning the outline into a script. In order to fully immerse the player, it was decided that choices shouldn’t be obviously ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but instead dependent on character relationships and the player’s attitude towards them. On the other hand, certain scenes needed to be written in such a way that they could be used in multiple contexts regardless of prior choice, which often necessitated writing around the branching parts rather than alluding directly to them.

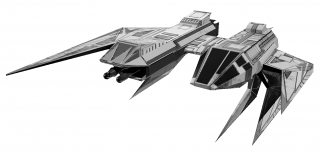

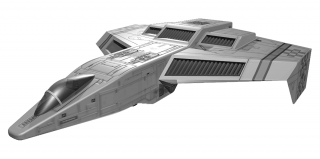

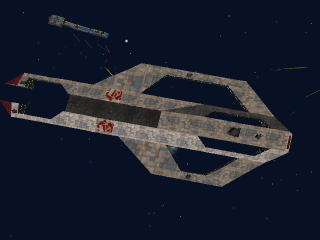

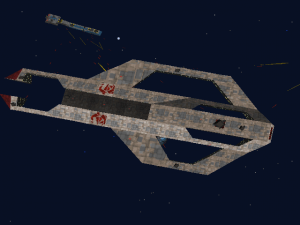

The film side was still intrinsically linked to the game dev side, especially when it came to art and design. Art Director Chris Douglas created much of the visual identity of the game. A veteran of the series since the Secret Missions add-ons, he built on the existing aesthetics for Terrans and Kilrathi to make them more distinct. The Confederation became more utilitarian, with chunky, blocky starships that would look good in both FMV CGI as well as the in-game, low-poly graphics. Meanwhile, Kilrathi ships became more detailed, with sharp asymmetrical profiles that resembled teeth, claws, knives or axes. This asymmetry had not been possible in prior Wing games, which used pre-rendered sprites that necessitated symmetry so they could be mirrored at different angles to save time, space and memory.

Back in Texas, Frank Savage was leading a group of programmers he largely picked himself. Savage had joined Origin during the development of Strike Commander, hired on Warren Spector’s recommendation due to his skills as well as love of Wing Commander. Having excelled in the previous project, he earned the position of Game Development Director for Wing 3.

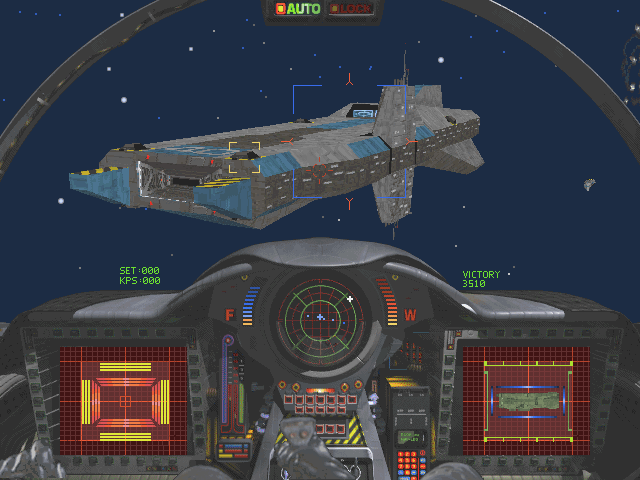

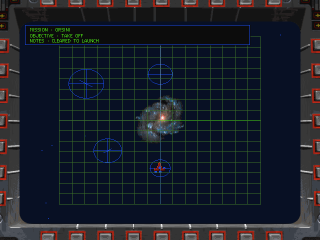

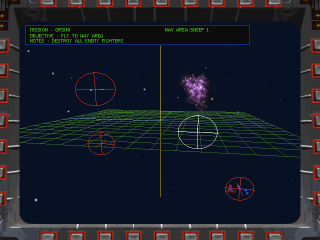

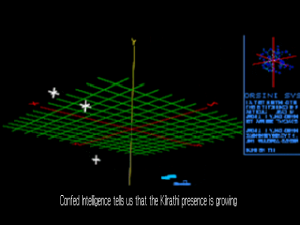

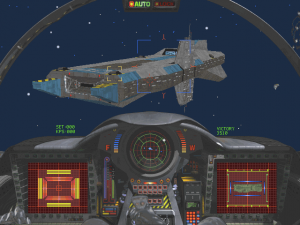

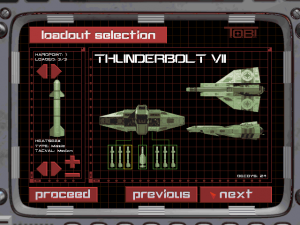

With Wing 2 as a baseline, the team aimed to refine and improve what already worked. They used a new iteration of the RealSpace engine originally developed for Strike Commander to bring gameplay into 3D with texture mapping. New features abounded thanks to the leaps in graphics and processing power. The navigation map, ostensibly near-identical to the previous iteration, can now be rotated in 3D as shown in the briefing cutscenes. Cockpit graphics are now presented with an impressive digitized look, but the option exists to toggle it off to see space largely unobstructed. Power distribution, a feature present in competitor space sim X-Wing, is also available. Players can maintain a balanced configuration, or allocate power to a specific system according to the situation between guns, shields, engines and damage repair.

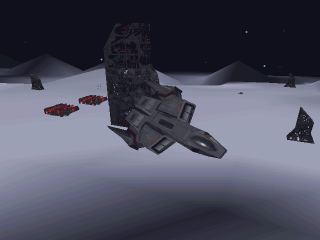

In an effort to expand the scope of gameplay, some missions take the player into a planet’s atmosphere to destroy ground targets. While interesting, this is a very basic addition without any real atmospheric physics to speak of.

Back in space, capital ships are much more detailed, allowing a player to destroy turret emplacements, or even fly within a carrier’s flight deck and destroy enemy fighters. During dogfights, hitting a fighter with gunfire briefly shows part of their shields, again adding to the level of detail. This is especially useful for fighting the redesigned Strakha stealth fighters, which return from Wing Commander II, as their shields will continue to appear on hit, even when cloaked.

This leads us to the headline feature of the game: those juicy, live-action FMV cutscenes. Following in the footsteps of Strike Commander, the keyword is once again ‘immersion’. Instead of a single pre-mission story scene before the briefing, the player can now freely wander the Victory and engage in conversations with wingmen and crew members.

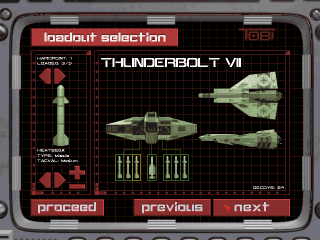

Conversation choices will either improve or lower a character’s morale. For wingmen, the lower their morale, the worse they will perform during missions, flying more recklessly, missing more shots, or making them less likely to follow orders. Certain actions during specific missions, as well as choices when talking to Comms Officer Rollins, can affect shipwide morale. This, in turn, makes the crew behave differently towards you. Finally, Rachel has her own morale stats, which may affect the available endings. For the first time in the series, Blair is the titular Wing Commander, with ramifications for both the storyline and gameplay. The player can now choose which wingman to fly with, as well as their loadout and fighter in pre-mission conversations with Rachel.

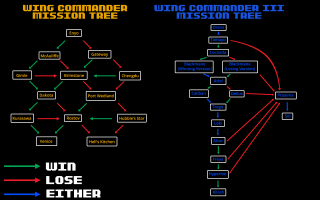

Finally, mission branching returns from the original Wing Commander, although it has been streamlined. Instead of the complex web featured in that game, Wing 3 opts for winning and losing tracks. Lose enough missions, and you will end up in an inescapable losing track that ends with the destruction of humanity. While much shorter than the winning track, this path features several unique cutscenes and a bad ending, so they’re worth checking out for completionists.

The leap from Wing Commander II to III feels enormous, even with the ‘missing link’ that is Strike Commander. It almost feels ludicrous that we went from mute talking heads and short pre-mission cutscenes to full-motion video and a complex storyline where choices outside the cockpit can affect both story events and relationships with other characters. On release, the game felt like an incredible jump in gaming technology. Origin and EA pulled out all the stops with the box contents too, indicating their confidence that this was as momentous a game as the original Wing Commander: Ship blueprints, a manual themed as an in-flight magazine, and an enormous poster were all included. While Wing Commander III is often discussed in terms of its FMVs, it is still a space combat simulator first and foremost, and in this aspect it does not disappoint. Flying feels more natural and balanced. Weapons fire has greater weight and precision, giving the player a sense that if they didn’t hit a target, it was their own fault. The game feels somewhat easier than its predecessors, but that could be ascribed to the dev team’s focus on fairer challenges. Capital ships, for example, require a more surgical approach than in previous games, where they were more like eldritch bosses to hit and run. Players take out turrets one by one, and can then deal with carrier fighters inside the hangar bays for ships that hold them. It’s a palpable difference.

All of this amounts to a game that comes together well and never feels bloated. The game’s soundtrack, composed by George Oldziey, is full of memorable tracks, with bombastic orchestrals and sober military marches. Every mission serves to either progress the story, explore character backstories and relationships, or frequently both. The gameplay loop becomes pretty addictive. After each mission, it’s fascinating to hear Rollins’s latest conspiracy theory on what command isn’t telling us about the war, or cheer up Vaquero, or, yes, flirt with Flint and/or Rachel. And after a round of interesting conversations, it’s exciting to jump back in the cockpit and stop Kilrathi from using devastating weapons on innocent populations, or covering convoys in daring escapes from enemy fleets.

This has the same loop as later Bioware RPGs, particularly Mass Effect. Deploy on a mission, come back to the ship and have interesting, multiple-choice conversations with your teammates about the mission, or their lives, and thus progress your relationships with them. It feels basic, but it is a clever way to weave characterisation and plot while keeping the game’s momentum going. The implementation of an affection system (referred to here as ‘morale’ due to the military setting) is also innovative, and wouldn’t become standard in story-based western AAA games for many years. While neither game originated such a system, it was popularized in Japan by Tokimeki Memorial, also a 1994 release, published six months before Wing Commander III. A fascinating example of simultaneous, independent creation of similar features across the ocean.

Despite all this praise for its innovation and game feel, there are a few choices in storyline and characterisation that warrant critique. Chris Roberts was not very involved with the development of Wing Commander II, and thus discarded much of the world building from that game. He also had no involvement with the novel Freedom Flight, co-written by Wing 2 co-director and lead writer Ellen Beeman, which was an exciting, pulpy romp connecting the first two games’ storylines. The reveal of Hobbes as a sleeper agent who betrays the Confederation completely undermines his entire character, as he represents the fact that not all Kilrathi are evil, bloodthirsty conquerors. By making the personality we know a false ‘imprinted’ one, the implication is that, indeed, all Kilrathi are evil and untrustworthy.

Hobbes explains his defection in a cutscene removed from the PC version, yet available in the 3DO and PSX ports.

This problematic racial analogy is compounded by the temblor bomb subplot. The Kilrathi have been characterized as a race of ruthless warriors with a strange, alien code of honor. The setting has always carried connotations of the Pacific Theater of World War II, and when we add the idea that the only thing that can stop this honor-bound culture is genocide, subtext moves much closer to text. This allegory to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is distasteful, even if it was (and still remains) a common narrative regarding the mass murder committed by the allies. Another aspect that has aged badly is the treatment of Cobra, the only female black character in the game, who is killed for the development of Blair’s character and his nascent rivalry with Hobbes. While there is some development regarding her trauma, she is mainly framed as an irrational, angry black woman… and then she dies.

Wing Commander III is, at the end of the day, a product of its time. It was a huge technological leap forward for the franchise, at a time when PC gaming had recently exploded into mainstream gaming with Doom. It proved that FMV games could be more than a gimmick, that they could be “done right” as Chris Roberts said. And it was a harbinger of things to come, a no-holds-barred production with an enormous staff list on both film and game development sides, and the funding to match. Its budget of $8-10m USD (adjusted for inflation) was enormous for a PC game of the time. While the modern view is that Final Fantasy VII was the first AAA game with its development budget of over $40m, Wing Commander III embodies the spirit of the modern blockbuster game: a star-studded cast, ambitious use of new technology, graphics that pushed current PCs to the brink, and an expansive list of new features. Concrete sales figures are hard to come by, but estimates go between 500k – 1 million, making it a heavy-hitter in the PC space of the time (where Doom sold 2M and Myst sold 6M, being the previous year’s biggest hits). It was, and remains, a touchstone in the history of video games.

The first port of Wing Commander III arrived in the same week as its MS-DOS release: a basically identical release for the Macintosh. But the resounding success of Wing Commander III resulted in several ports to gaming consoles. In the mid-90s, however, only the newest generation of consoles could hope to handle the game.

The troubled 3DO had the honor of landing the first console port in 1995. It was something quite special, developed in-house by Origin. The FMV cutscenes look significantly sharper in the console. Compression artifacts are rarer, and characters ‘pop’ more. The in-flight radio messages, conveyed as green monochrome videos in the PC original, are now in full color, including brand new comm messages. But that’s not all, as the game includes several cutscenes that didn’t make it into the PC version. At regular points in the story, the player can watch brief news stories that give a more general perspective on the universe and a civilian, journalistic viewpoint on the war. But perhaps the most important addition is a hologram left for Blair by Hobbes after his betrayal. In it, he explains that despite the imprinted personality, he had come to respect Blair as a warrior. He declares that the Hobbes he knew never truly existed, as it was all a personality imprint. While this clarification was sorely needed in the original version, it doesn’t make this plot development any better.

In-flight, the 3DO had some interesting changes. First off, loading times are no longer a tedious slog like the PC version was on contemporary systems. Ship interiors have been removed, probably due to processing reasons, but the greater change is in mission layout. In order to give the player a more ‘arcade’ shooter feel, the game is now more fast-paced and less strategic. Weapons recharge faster, enemies are weaker but more numerous, and some missions no longer follow the original briefings, still present in the game. The overall story remains the same, however. While the resolution is lower, as the 3DO could at best output 480i, ships have been retextured, with some looking more detailed than their PC counterparts. Planetary missions are gone, replaced with cutscenes. While no great loss, it does mean the final mission (a difficult atmospheric flight gauntlet with a precision bombing run), was removed. The 3DO port was ambitious, if difficult to control with the limited buttons of the default controller. It’s compatible with the Flightstick Pro controller, and this was reportedly a more optimal way to play.

A port for the Sony PlayStation followed in 1996, a logical move considering the console’s runaway success. Electronic Arts took the reins this time, with some QA support from Origin. This version retains the newly added cutscenes from the 3DO version, and cutscene quality is only slightly lower. Ship interiors are still removed, as are planetary missions. But this is where similarities end, as missions are now basically carbon copies of their PC versions, and there’s no evidence of the ship retexturing from the 3DO port. The greatest loss for immersion are cockpit graphics, completely absent from this version rather than being an option as in the 3DO port. Possibly the most frustrating part of this port is the amount of times one is confronted with the loading screen.

The next port brought Wing Commander III back to the PC, as part of the Kilrathi Saga compilation of the first three numbered entries in the franchise for Windows 95. Released in 1997, this compilation originally sold poorly as players were reluctant to re-buy the games, but as MS-DOS faded into irrelevance, copies of the compilation became highly sought-after as the only way to play the games in modern PCs until DOS emulation could catch up. The Kilrathi Saga version of Wing Commander III added support for HOTAS joysticks, allowing for better handling of thrust in flight. The MIDI soundtrack has been replaced by digitized recordings, although these proved to be of relatively poor quality. This collection has never been released for digital download, unlike the MS-DOS original.

There are at least three known cancelled ports of the game. The port to 3DO successor M2 never materialized as that console went unreleased. It was reported that Atari was brokering a deal with Electronic Arts to bring their games to Jaguar, with Wing Commander III destined to its Jaguar CD add-on, but reports of this are all that remain. Then we have the odd case of the Sega Saturn port, which had cutscenes showcased at the very first E3, and was part of an ad campaign by Electronic Arts, promoting the ports of the game. However, despite several magazine reports throughout 1995, screenshots shown might not have been running on Saturn hardware, and little else was seen before the port was quietly shelved.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Colonel Christopher “Maverick” Blair (Mark Hamill)

You are Colonel Christopher Blair, hailed as a war hero for your many exploits in the Enigma campaign. Your old carrier, the Concordia, was lost in a great battle alongside many of your friends. You are in a relationship with Jeannette “Angel” Deveraux, whose whereabouts are unknown. You are a level-headed mentor but your eyes betray an extreme sadness and weariness about humanity’s long war with the Kilrathi. Your callsign is blank, but it is now canonically “Maverick”. You no longer have blue hair.

Captain William Eisen (Jason Bernard)

Your CO aboard the TCS Victory. Captain Eisen is a no-nonsense kind of leader and runs a tight ship, but don’t let this fool you: he cares deeply about every single person under his command. If at any time you exhibit unprofessionalism or rash impulsiveness, he will take you to task on it. So you better shape up, mister.

Admiral Geoffrey Tolwyn (Malcolm McDowell)

Despite the mutual respect you had both achieved over the course of the Enigma campaign, Tolwyn’s more twisted personality in the late days of the war has made you extremely wary of him. He has manipulated events for the Behemoth operation, which he sees as his crowning moment of glory.

Major James “Paladin” Taggart (John Rhys-Davies)

Losing his Sean Connery-esque looks in his old age, Paladin might not be in the cockpit, but he’s still fighting the good fight. Now involved in covert operations, he worked closely with Angel’s unit in its infiltration of Kilrah. He knew Angel was dead. He didn’t tell you. And yet, at humankind’s darkest hour, he might be the hope we need.

Major Todd “Maniac” Marshall (Tom Wilson)

After several setbacks in the Morningstar project, Maniac’s stock has plummeted, not that he’d ever admit it. Still a reckless, if talented, pilot, he’s been reduced to a braggart. He holds a one-sided rivalry with you, and is generally seen as the ship’s asshole. Unlike everyone else, however, treating him like dirt makes him go harder in the cockpit.

Colonel Ralgha “Hobbes” nar Hhallas (Voice: John Schuck)

While he held a place of honor aboard the Concordia, Hobbes is regarded with suspicion by the crew of the Victory. He requested to be removed from the flight roster as other pilots refused to fly with him, and starts the game as the ship’s XO. You reinstate him immediately, knowing his skills. While still a proud warrior, he’s become more sullen and meditative.

Chief Tech Rachel Coriolis (Ginger Lynn)

The perky Rachel is as flirty as she’s in love with her job. She’s happiest when deep in the guts of a fighter, tuning it just right to make it sing. She helps you with ship selection and loadouts, and gives you a quick evaluation of your mission results after returning to the Victory. You might also end up in a romance with her, should you make the right moves.

Lieutenant Robin “Flint” Peters (Jennifer MacDonald)

The latest in a long line of fighter pilots, Flint lives for flying. She’s eager to prove herself, but can often be impulsive. She is also romanceable, although her canonical ending is as your wingman during the Kilrah bombing run, where she will sadly be lost in action.

Lieutenant Winston “Vagabond” Chang (Francois Chau)

Always ready to play some poker and take rookie’s lunch money, Vagabond’s friendly personality belies a man scarred by a dark past. Formerly involved in super-weapons programmes, he carries enormous guilt over his part in the Pax VII incident where millions of civilians died during a test gone wrong.

Lieutenant Ted “Radio” Rollins (Courtney Gains)

In charge of comms in the Victory, Rollins has a conspiratorial mindset. His instincts often prove true, however, as the crew of the embattled carrier is kept in the dark on the truth of their operations.

Lieutenant Laurel “Cobra” Buckley (B.J. Jefferson)

Traumatized by spending most of her formative years in a Kilrathi prison camp, Cobra’s hatred for the Kilrathi runs deep. She suspects Hobbes of being a traitor and will not fly with the Kilrathi defector. She’s a fantastic pilot, but carries the weight of what she saw at the camp and this can make it difficult to interact with her.

Major Jace “Flash” Dillon (Joshua Lucas)

Flash is your typical arrogant hotshot who was a big deal at the academy but has yet to see actual combat. He arrives on the Victory as the test pilot for the cutting-edge Excalibur fighter, and is generally insufferable.

Lieutenant Mitchell “Vaquero” Lopez (Julian Reyes)

A romantic who can often be found at the bar strumming his guitar, Vaquero is a young dreamer. You quickly take a liking to him due to his laid-back attitude and zest for life.

Colonel Jeanette “Angel” Devereaux (Yolanda Jilot)

Formerly the CAG of the TCS Concordia, Angel has become involved in covert ops and managed to infiltrate the Kilrathi homeworld. You are unaware of this, and simply know she’s gone radio silent in some undercover operation.

Prince Thrakhath nar Kiranka (Voice: John Rhys-Davies)

The Crown Prince of Kilrah returns, and he’s holding a grudge against you, personally, for getting in his way so many times. He has nicknamed you “The Heart of the Tiger”, and seeks to hurt you as much as possible while carrying out the Kilrathi campaign to exterminate the human race.

Melek nar Kilra’hra (Voice: Tim Curry)

Thrakhath’s right-hand cat, Melek is an able commander loyal to his lord, if sometimes befuddled by human vocabulary.

Kilrathi Emperor (Voice: Alan Mandell)

The ruler of the Kilrathi Empire, he has reigned since at least the time of Wing Commander II, possibly longer. He is Thrakhath’s grandfather, and little is known about his personality. He rules the Empire with an iron fist, in the finest Kilrathi tradition.

Image Credits:

MobyGames

Super Adventures in Gaming