For most of the 1980s, Origin Systems was best known for their groundbreaking work in the Ultima series. Ultima defined the CRPG and broke ground with each new iteration, gaining Origin Systems, and especially its key figure, Richard Garriott, considerable fame within the industry. The history of Ultima can be found elsewhere on this site, but Origin released other games, of course, many of which were also RPGs. Its reputation as ‘the Ultima guys’ was well-earned.

All of that changed in 1990 with the release of Wing Commander.

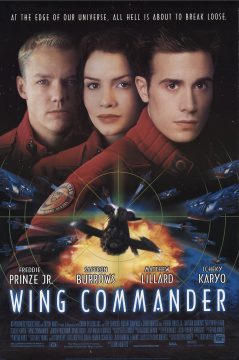

Much like Garriott came to be defined by his creation of Ultima, so did Chris Roberts come to be known primarily for his magnum sci-fi opus. Wing Commander put space combat simulators on the map, causing a boom in the genre not seen since its apex in the 1990’s. Throughout multiple games, ports, and adaptations to other media from cartoons to novels to a Hollywood film, Wing Commander defined Origin’s ’90s just as much as Ultima had defined its ’80s.

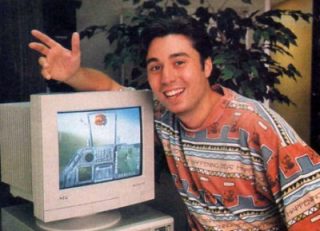

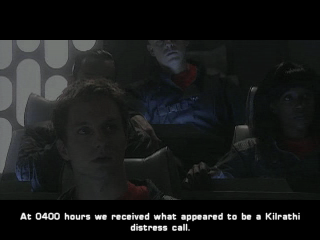

Chris Roberts – (left to right) Showing off Strike Commander in 1993, cameo in Wing Commander IV, and at GDC 2012

Born to an English father and American mother, Chris Roberts grew up in Manchester, England, where his father was a lecturer in Sociology. This gave young Chris the opportunity, rare for the time, to get acquainted with personal computers. As a teenager, he would learn BASIC from one of the founders of BBC Micro magazine. This resulted in his games being published in the style for BASIC games of the time: as code transcripts one had to manually type up. From these humble beginnings, Roberts went on to publish boxed games at retail at a time when British computer culture was experiencing a boom in growth. Little did he know that years later, he’d be living in Texas, working with one of the biggest names in the business.

It was a series of lucky coincidences that led to Roberts finding himself working in the same Austin, Texas offices where the legendary Ultima series was developed. His father was offered tenure at the University of Texas, an opportunity no academic would’ve turned down. Roberts planned to join his family there for a gap year before starting studies at the University of Manchester, taking advantage of the free time to continue work on his first Commodore 64 game.

But the young developer found himself enchanted with American pop culture, especially the more advanced computers available (and, to hear him recount it, the attention from girls caused by his English accent was also a factor). He was looking for an artist for his game when he saw a painting by Denis Loubet in a local gaming shop, its owner offering to put them in touch. Loubet was a frequent collaborator of Origin Systems, and had just been brought in-house full-time. He was impressed with the young British developer’s game, and brought him to meet Lord British himself, Richard Garriott.

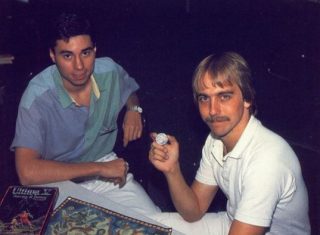

Chris Roberts with Richard Garriott in 1988

Chris Roberts with Richard Garriott in 1988

Roberts, however, had never heard of Ultima. Computer gaming culture was, at the time, sharply divided by the Atlantic, with many British gamers unaware of the legendary RPG saga. But Roberts liked what he saw, and agreed to work on his project as a freelancer. With Loubet on art, this became his first game with Origin: Times of Lore. Unfortunately, its release in 1988 was impacted by Origin’s curse: the success of the Ultima series, which overshadowed their other projects. Times of Lore did well enough, even against Origin’s port of Ultima V to the Commodore 64, and managed to be innovative in its own way. The game took the RPG interface championed by Ultima one step forward by discarding written commands in favor of a point-and-click menu with evocative icons.

His follow-up, Bad Blood, didn’t find much of an audience, as it put off Origin’s devoted RPG gamers with its action-oriented gameplay, whereas audiences looking for an arcade experience were not, at the time, looking at Origin to provide them. Roberts was too busy to focus on the game’s critical failure, however, for he was hard at work on the ambitious sci-fi game, Squadron.

Starting life as a grand, 4X strategy game, Roberts decided to shift the perspective to a more gripping first person view as a fighter pilot. But there was a problem: graphics. Transparent vector visuals had been iconic in arcades and home computer games alike, such as Roberts’ acknowledged inspiration for Squadron, space-sim classic Elite. But those games looked positively primitive to gamers by the late ’80s, and evolving that look would have monstrously spiked the already elevated system requirements Origin was becoming infamous for. Instead, the team chose scaling 2D sprites.

Origin was sold on the prototype, and gave Roberts their full support for the project. There was only one problem: they wanted it out before the end of the year. Roberts and his growing team, which now included Producer Warren Spector and writers Jeff George and Glen Johnson, got to work. The idea was for Squadron to fully immerse the player through its space combat gameplay and a detailed storyline full of evocative characters and a space opera’s scope. As these things usually go, Squadron became Wingleader, and was presented to the public with this name in the summer of 1990 at the Consumer Electronics Expo.

Much like Ultima, the tale of Wing Commander as a series is inextricably tied to Origin Systems and its acquisition by Electronic Arts in 1992. As of this writing, Wing Commander is best known to the average gamer as a footnote in the convoluted story of its spiritual successor, Star Citizen. But as we’ll see in this series, its groundbreaking nature would extend far beyond that ambitious first game.

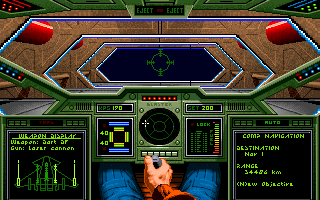

Wing Commander III (IBM PC)

Wing Commander III (IBM PC)

Each new installment would push the envelope in new and exciting ways. Wing Commander II offered several fully-voiced cutscenes (as a Speech Accessory Pack add-on, sold separately). The third mainline game in the series jumped to 3D ship models and, famously, replaced its 2D cutscenes with full motion video. The cast, replete with beloved sci-fi and fantasy actors, included Mark Hamill as the series lead, alongside Tom Wilson as Maniac (Biff Tannen in Back to the Future), John Rhys-Davies (years before his Lord of the Rings role as Gimli) and Malcolm McDowell, who seemed to play a villain in every conceivable genre film of the 1990s.

Building on this success, Wing Commander IV brought an expanded budget for a marked increase in film quality and player choice. The follow-up Wing Commander: Prophecy was the first in the series to showcase the more detailed real-time graphics which 3D accelerator cards could now provide for PC gamers.

Indeed, the ’90s were the age of Wing Commander. The franchise exploded, with numerous spin-off games and a growing universe that encompassed novels (which included brand new stories set between the games), a trading card game, and even an animated series. While not the first video game series to expand into other media, its tragic war stories stood apart from competing adaptations of more cartoony, kid-friendly characters such as Mario and Mega Man. This culminated in the production of a Hollywood movie… which flopped.

Just as soon as the series took the world by storm, by the early 2000s Wing Commander was dead. This is its story.

Image Credits

Screenshots for WC1, 2, 3 and 4 from Moby Games

Photograph of Chris Roberts at GDC 2012 from Flickr, shared under Creative Commons BY 2.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0

WC3 Staff Photo of Chris Roberts from WCCIC

Photo of Chris Roberts and Richard Garriott from the Digital Antiquarian

Chris Roberts in WCIV screenshot from WCCIC

Prophecy screenshots from WCCIC