- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

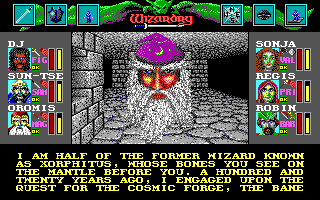

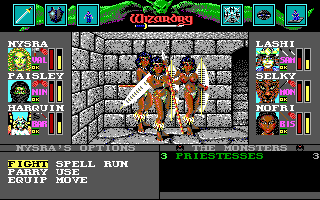

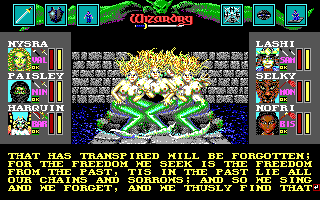

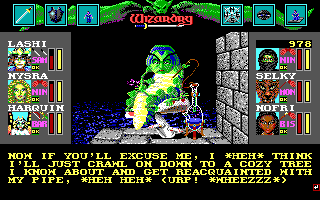

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

Most of the PC version screenshots were taken from The CRPG Addict and DJ OldGames.

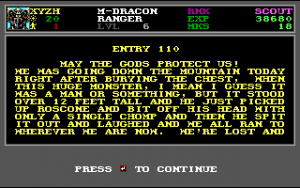

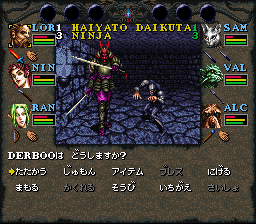

If D.W. Bradley had performed careful corrective surgery with a scalpel on the Wizardry series in The Heart of the Maelstrom, then Bane of the Cosmic Forge is the equivalent of him taking a butcher’s hatchet to it. The title screen still only shows the typical fantasy races, but in an attempt to emancipate from the Dungeons & Dragonsinfluence, Bane introduces a whole lot of more exotic creatures for the party. Most of them are anthropomorphic animals – the canine rawulf, a cat people called felpurr, and the less inventively named lizardmen. The reptile faction is completed by the Dracon, who have the unique ability to breath acid on their enemies. The fairies lack in physical strength, but they are fast and hard to hit due to their small size. The mook, finally, are essentially just the wookies from Star Wars.

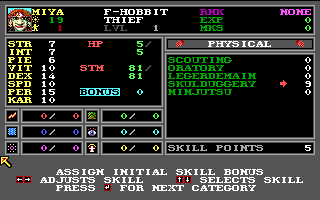

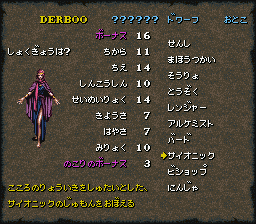

To make more space for meaningful differentiation of all those races, the rules have been given much more complexity: Characters are now built with eight base stats instead of six – agility got separated into dexterity and speed, and there’s now a “personality” value for interaction with NPCs, too. Luck got replaced by the much more obscure “karma”, which is only rolled once upon character generation and never increases upon leveling up. For the first time in the series, characters are no longer handled gender-neutrally, and women actually get a lower strength, but higher personality and karma. They also get a new exclusive class: the Valkyrie.

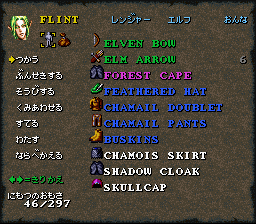

The class system in general has been expanded a lot. In addition to the Valkyrie, which is a variation on the Lord, finally there are mixed thief classes: Bards get some mage spells and carry a lute that can put enemies to sleep, while Rangers are predestined archers and get access to the Alchemist spell book. That’s right, there are two new schools of magic, the Alchemists and Psionics. Monks are even more focused on unarmed combat than Ninjas, and can cast Psionic spells (opposed to the Ninjas’ Alchemist magic).

As all these new spell types suggest, the magic system has been heavily revised as well, and hardly resembles the Dungeons & Dragons inspired methods of the earlier games. The spells are now divided into six “elements” (fire, earth, water, wind, mind and spirit), and the different caster types get to learn different spells in each category (although there is some overwrap between them). Mightier spells can still only be learned at a sufficiently high character level, but the strict spell level distinction doesn’t exist anymore. Rather, casters get a separate pool of magic points for each element based on the number of spells they learned in that category. To avoid ending up a lot of useless low-level spells, high level mage users can invest more spell points upon casting to make them more effective.

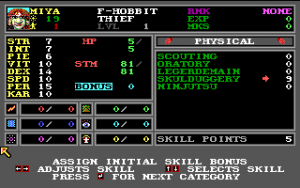

Completely new is the skills system. Wizardry V had the swimming skill that improved upon use, but now there’s a whole range of new abilities to take care of. These include combat skills with each weapon type – the weapon range system has been carried over from Bradley’s first game – knowledge-based skills for the spell schools, the use of scrolls and spell books or identifying enemies, or kirijitsu, a samurai or ninja’s ability to find vulnerable spots on enemies. Finally, there is a number of physical skills, including a separate scouting ability that makes it easier to detect hidden treasures and mechanisms, music for bards, as well as legerdemain, skullduggery and ninjitsu, which represent the thief actions steal, unlock and hide.

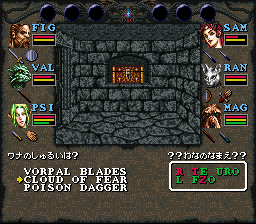

The thief abilities in particular are no longer just dice rolls, but represented by little mini games. Locked doors just show a row of flashing numbers, and only when pressing the button as all are above the requirement, as indicated by colored rectangles, the opening is successful. It’s also possible to break open the door with a strong fighter, which shows a rapidly flashing gauge, similar to “strength” based challenges in many action games. However, with the speed these run on a normally fast computer (even at the time), these are much too fast to play as reaction tests, and more or less just a visualization of the stat-based/random process. More involved is disarming trapped chests: Each character gets a chance to examine the device, resulting in one or more letters to show up in no particular order. The player then has to go through the list of existing traps, finding a name that matches up with all the discovered letters.

But thankfully the use of skills is not strictly limited to those classes, and once a single point has been invested into a skill, it carries over upon class change, making the job system even more useful than before. So if a character transitions from being a thief to a fighter, all the skill points carry over, and they can continue to invest more points into them, even if they are alien to the new class (equipment limitations still apply, though). The system to increase proficiency is a hybrid one: Characters get a small number of points to distribute when they gain a level, but the weapons and most of the physical skills can also be improved through frequent use.

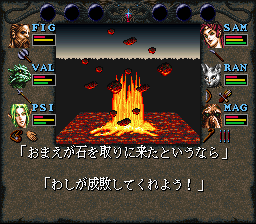

But really the most significant change comes with the structure of the whole quest. At the beginning, it’s not at all certain what the party is actually trying to accomplish. The manual tells the story of an evil(?) king and his wizard, who long ago discovered the Cosmic Forge, a magical pen that makes everything true its owner writes with it. But the game takes place centuries after both the king and his wizard mysteriously vanished, and it doesn’t become clear how current events relate to that until much later, so for most of the game it’s just a “press on by exploring every nook and cranny” affair. While there is one critical path to most of the dungeon, the loose approach to the party’s motivations carries on until the very end, where it is possible to achieve several different outcomes.

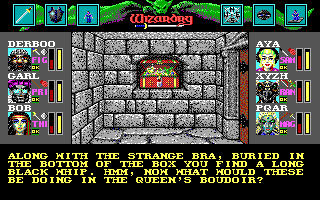

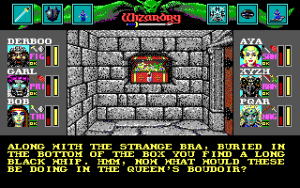

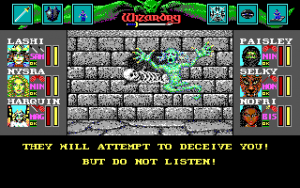

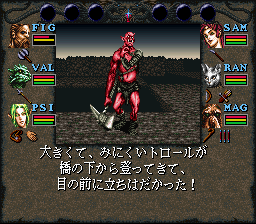

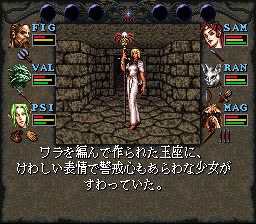

Also very distinguishing from previous games, Bane of the Cosmic Forge is the most pure dungeon crawl experience in the whole series. After the party enters, a grate closes behind them, and they’re trapped. There is no going back into a save town to heal and restock, the party is fixed and has to get along with what is found within the dungeon. Luckily, the area isn’t entirely desolate, though. There is a number of NPCs to find, who can be interacted with in the same way as in Heart of the Maelstrom, and some even stock items to buy. The only ways to heal and replenish stamina – which gets used up by attacking and using skills – and spell points, are by finding rare healing fountains (but careful – there are also poisoned ones) or by camping within the dungeon, which of course leaves the party open for surprise attacks from monsters.

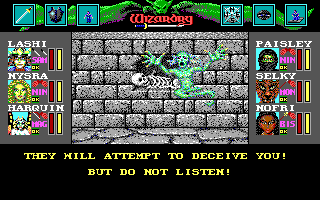

Encounters are balanced in a particularly mean way – a well-rested, properly leveled party will have trouble to get any random encounters at all, while the monsters seem to keep appearing on purpose to wail on already battered heroes. The game is no less brutal in killing off adventurers than its predecessors, but this time, players are stuck with what they got. There are scrolls and potions to bring a character back to life, but they are in short supply, and most of the time the game simply requires a save-scumming approach to survive. If the game had retained the hardcore consequential approach of the old games, it would be just impossible, but fortunately Bane of the Cosmic Forge allows free saving everywhere.

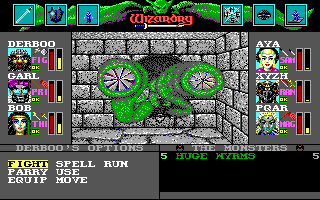

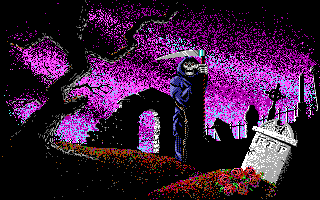

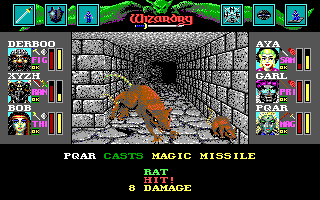

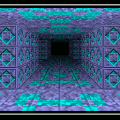

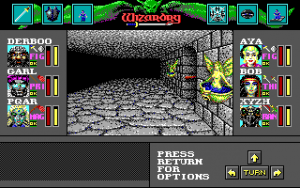

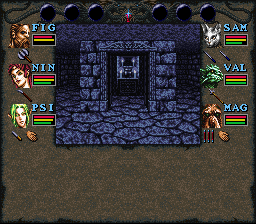

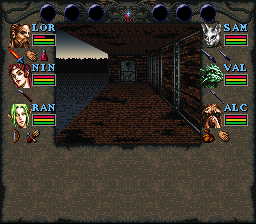

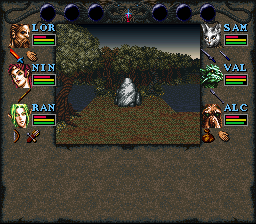

Bane of the Cosmic Forge finally got rid of the wireframe dungeons and 4-color monsters, that much can be said about its graphics. It’s still glaringly obvious that Sir-Tech was only desperately playing catch-up with the advancement of technology, and Bradley was still mostly on his own creating the entire game and all its assets. Contrary to earlier promises by the publisher, the game only used 16-color EGA graphics. What’s worse, though, is the fact that the entire dungeon is made up of only one type of wall. Every area looks exactly the same, no matter if it’s described as a castle, a pyramid, underground mines or a forest. Yes, Wizardry VI lets players explore a forest made out of grey brick walls! There’s also no music whatsoever, and the sound effects are only static noise. Coming at the tail end of 1990, the year when Wing Commander sold countless VGA and Soundblaster cards, the presentation seemed rather miserable. Even RPG fans could look forward to Might and Magic III and Eye of the Beholder in all their 256-color glory just a few months down the line.

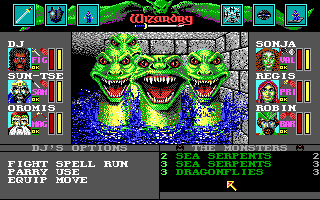

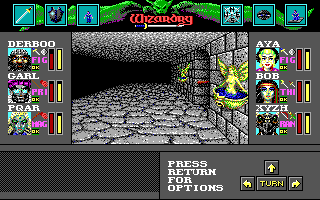

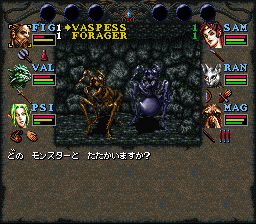

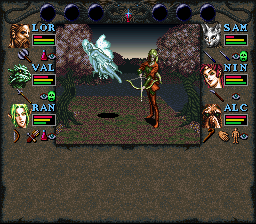

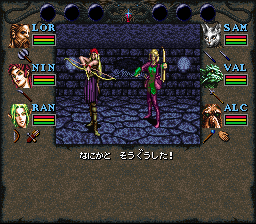

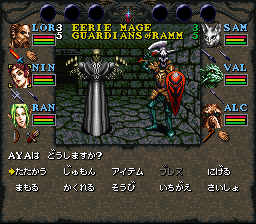

There are also some weird interface issues with Bane of the Cosmic Forge – the party members are distributed to the left and right of the 3D window, but the front row is still made up counter-intuitively of three characters. The new mouse interface includes strafing for the first time in the series, but it has to be toggled with a separate button, which usually results in more clicks than just turning around each corner the old way. Characters are now represented with a small portrait, but the selection is rather limited, especially for the animal races. It’s also not possible to get to characters’ status screens by clicking on the portraits, everything just goes through text-based menus.

The different computer versions are all largely identical to the IBM original – it’s funny looking back at old Amiga magazines and see reviewers scoff at the graphics of a port for looking just as bad as the PC version. Even all the FM Towns adds visually is a high res Japanese font. At least it has a kicking redbook CD soundtrack, but it seems strangely inappropriate for a game looking that bleak.

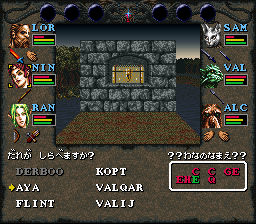

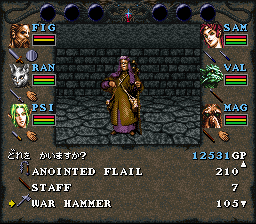

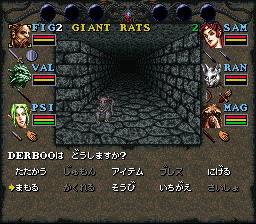

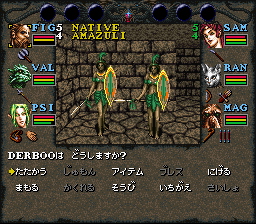

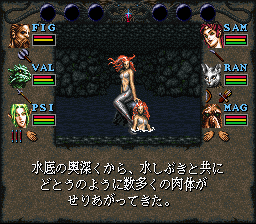

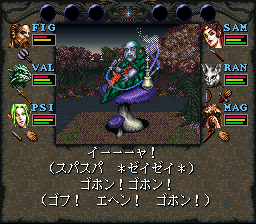

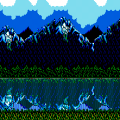

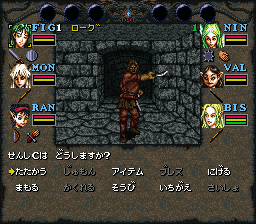

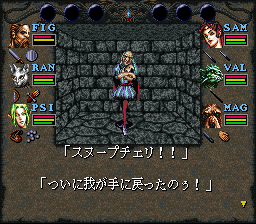

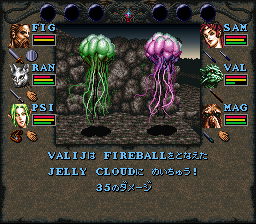

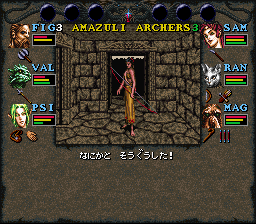

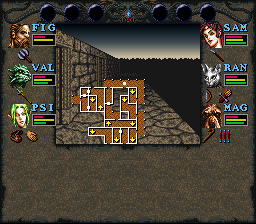

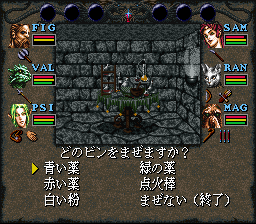

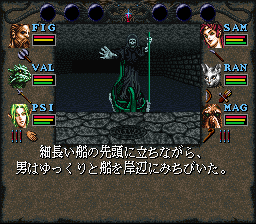

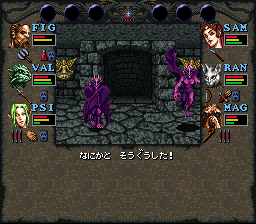

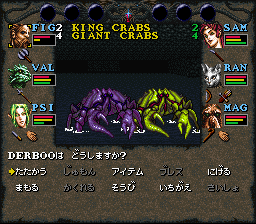

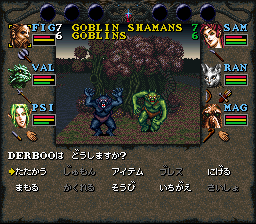

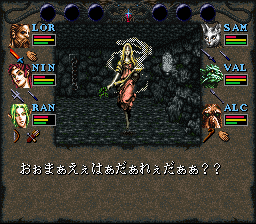

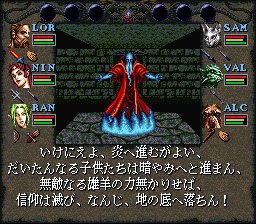

Leave it to the Super Famicom version to fix the graphics. It still has technically only three different wall tilesets – castle, cave and forest – but with some color changes that goes a long way. Many NPCs that would looks just like average enemies got their own unique sprites, too, and the pixel art is fantastic. All creatures are redesigned from the ground up, but there’s also some more self-censoring: The original game went a bit overboard with topless female enemies, and even though the game never had to deal with Nintendo of America, they are appropriately covered up in the console version. The soundtrack, while not as splendid as the FM Towns audio, is still reasonably atmospheric, too. The icing on the cake is a freely accessible automap, since Wizardry has finally reached a size and structure where using graph paper almost seems like more trouble than it is worth (although modern mapping programs solve that problem).

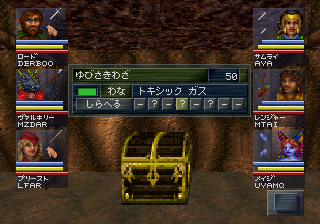

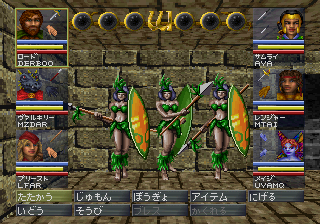

On the Saturn, Wizardry VI was bundled together with its sequel, Crusaders of the Dark Savant, and published by Data East. With the advantage of hindsight, rules concerning spells and skills were adjusted to match Wizardry VII, even though some of them remain useless for the entirety of this game. The treasure chest mini game has been changed quite a bit – upon pressing the “inspect” button, the chosen character takes a guess for the nature of the trap, with eight buttons displaying either “?”, “-” or as an empy space. The “-” fields are off limits, while the aim is to find the empty button. When it’s not among the recognized parts, it’s possible to check again with “inspect” to make sure, but every action is measured against a flashing light – whenever the treasure hunter acts on a red signal, the trap is executed. Since the light flashes very fast even at high skill levels, untrapping chests is more dangerous than ever in the series.

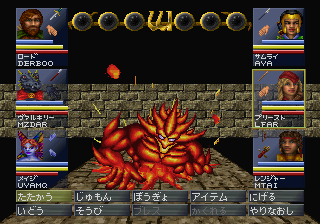

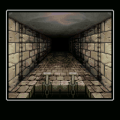

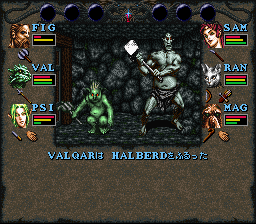

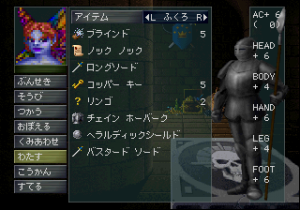

The character portraits are also taken from Wizardry VII to smoothen the transition from one game to the other, and they’re the same as on PC. The enemies, on the other hand, are entirely new sprites that are not based on any other version, while the dungeon walls are made of low-grade polygon graphics. The sprites are the most refined of any version, but the dungeons look very ugly. Even though there is some variety, it’s quite unevenly distributed – the game features an earthy-looking tileset for the mountain area, but the mines revert back to brick walls. Same for the river styx and the swamp – the standard brick walls are overused throughout. The somewhat counter-intuitive menus and load times do the rest to ensure this port’s place below the Super Famicom version.

The only problem? Neither the Super Famicom port nor the Saturn version of Wizardry VI ever left Japan, and contrary to the earlier games most of the text outside of monster and item names cannot be switched to English. It is possible to kind of get through the game with a guide, since dialogs run once again mostly automatically, but given the huge amount of flavor text that fills the game, this is not very enjoyable. There is a fan translation patch for the Super Famicom port, though, which is a bit unpolished, but at least fully functional.

Comparison Screenshots