- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

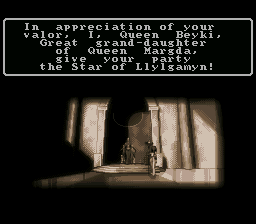

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

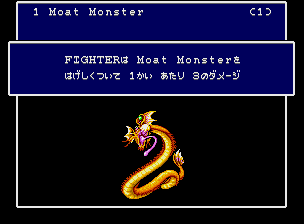

At first, Wizardry wasn’t much of a multiplatform title – it remained a system exclusive to the Apple II until after Legacy of Llylgamyn introduced the new windows-based interface, which was then used for almost all ports of the first two scenarios as well. In 1984, Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord was finally ported over to IBM PCs, not to be run in an MS-DOS environment, but booted directly from disk. It introduced all new monster graphics which were then used for subsequent home computer versions. In cooperation with a Japanese team at ASCII, Robert Woodhead created a kind of virtual machine especially for Wizardry, to make porting it to individual platforms much easier. ASCII brought the game to pretty much all home computers out in Japan. Since they were all running on the same basic engine, they only differed in graphics, which look best on PC-9801 thanks to the higher resolution. These new versions also had a number of balancing differences to the original Apple version.

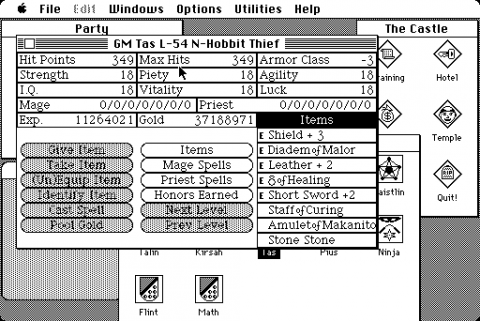

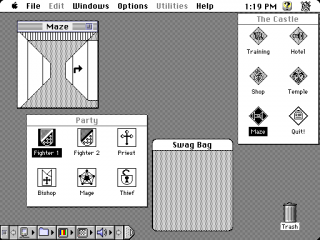

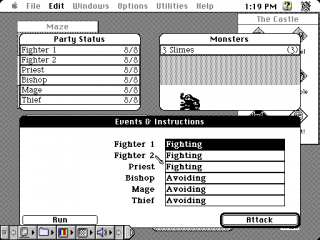

According to an interview Woodhead gave to the magazine QuestBusters in March 1987, the plan was to bring Wizardry to all the Western home computers as well, including the Atari ST, Atari 800, Amiga and C64, but only Commodore’s 8-bitter did get it in the end. The Apple Macintosh version didn’t use the virtual machine, but got completely new graphics and a new engine embedded in the Mac OS built-in interface. This version was the most user friendly for a number of slick-interface-related reasons (especially combat was much faster thanks to drop-down menus with typical default selections for the entire party). But its greatest advantage was the ability to save inside the dungeons and then go back to that party later, eliminating the need to get back to the town each time before quitting the game.

Wizardry was never big in Europe – only the French received translated versions of the original trilogy on Apple II – but in Japan the franchise had already caught on a life on its own by 1987, and ASCII had produced Japanified new variants of the games for the Famicom and MSX2 (the original MSX had been pretty much the only notable platform left out the first time around), with a soundtrack by anime musician Kentarou Haneda (1949-2007) and new monster art by illustrator Jun Suemi, whose designs have become so popular that most recent Wizardry games still base their graphics on them. The Famicom version was also the first Wizardry title to eschew wireframe dungeons in favor of monotonous, but at least textured brown walls. Dungeon level 6 to 8 in Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord have their layouts changed for some reason. The change seems even more puzzling considering that these levels are completely optional, but they’re kept through all future versions based on this. Also for reasons unknown, ASCII switched the second and third episodes around this time. For the American NES release Asciiware waited for Knights of Diamonds to come out to bring them back into the original order, but in the end they never got around to releasing Legacy of Llylgamyn in the West. It’s no surprise that the NES versions don’t support importing the party between episodes, but in Japan ASCII actually distributed a tool called Turbofile, which allowed to store save files separately, and thus enabled the transfer even on the cartridge-based console.

With the exception of the PC Engine port, which was done by a different team at Naxat and had its own soundtrack, graphics set and balancing, and the Wonderswan’s strange melange from both the “mainstream” and PC Engine branches, all subequent versions built on the Famicom game as their template, although many added improved and more diverse graphics and even new mechanics. The three scenarios now always appeared bundled into one package (safe for the handheld versions), re-enabling the file transfer, although for balancing reasons these versions always do it in the “inheritance” fashion introduced in Legacy.

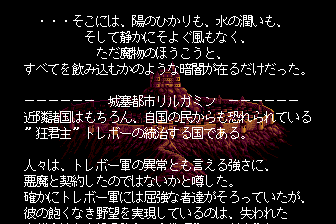

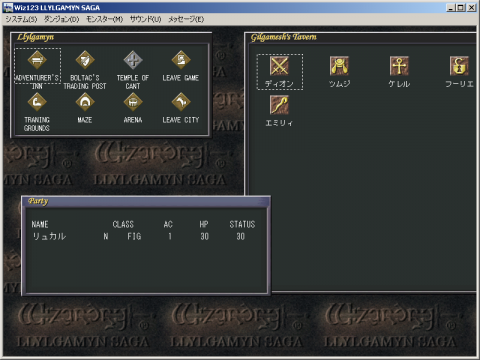

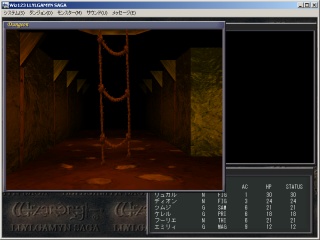

The Story of Lllylgamyn, which combines all three episodes on the Super Famicom, was released only for the Nintendo Power flash cartridge in Japan, and came astonishingly late – it became available in 1999, even after the Saturn and PlayStation compilations. But it is easily the best version, as it has the most beautiful graphics and solves the problem of thieves being useless in combat by including the “hide in shadows” skill that was first introduced in Wizardry V. It also displays an icon next to characters that are ready to level up, and makes things much more comfortable by providing an automap for casters of the DUMAPIC spell instead of just putting out the current coordinates. Soliton’s Llylgamyn Saga bundle for PlayStation, Saturn and Windows has more detailed monster illustrations, but the dungeons are made of ugly pre-rendered graphics. It also supports a free automap feature, and contains a pre-built party at a higher starting level to ease the entry a bit. The Windows version, oddly enough, seems to channel the old Macintosh port, as it uses mostly the same interface layout.

All Japanese versions feature a surprisingly rich set of options, as the player always has the choice to play in the trademark wireframe dungeons, and monster names, item names and status messages can be individually toggled between Japanese an English text. The 32-bit Lllylgamyn Saga even includes the home computer monster graphics, although not in the hi-res splendor of the PC-9801.

Balancing varies haphazardly in between ports. The NES version provides a very easy start; it’s no problem going right down to the second dungeon floor and kick some ass with an unleveled, unequipped party, which would have been suicide on home computers. Afterwards it gets harder quite fast, though. On the PC Engine the first floor is laughably easy as well, while on the second the party keeps running into enemies that formerly only inhabited the third, especially the dreaded ninjas, capable of beheading heroes with a single strike. Spell levels are also shuffled around each time. The later console versions mostly restore the balancing, though.

A perfect example for the many subtle yet significant differences is the loot gained from the “mid-boss” fight on the fourth floor of the original scenario, which distinguishes the “Proving Grounds” from the dungeon proper: On the Apple II the enemies just drop some random items, while the first ports for other computers introduced fixed swag, which includes the Ring of Death, which is worth a whooping 25,000 gold pieces when sold at Boltac’s Trading Post, but continuously drains the HP of the character that carries it. On computers it is harmless until identified by a bishop; on the Super Famicom it’s deadly from the start, but can be switched between party members to keep them alive; on the PC Engine, on the other hand, it is a cursed item that sticks to the one who finds it, even without being equipped, making that character’s death almost guaranteed.

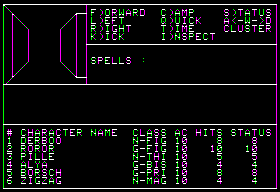

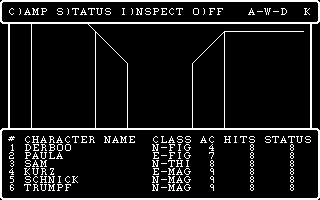

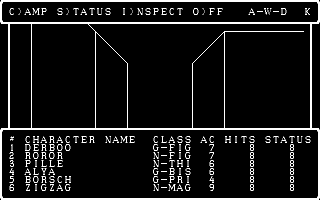

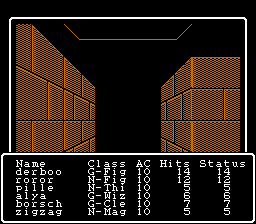

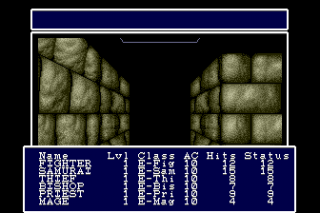

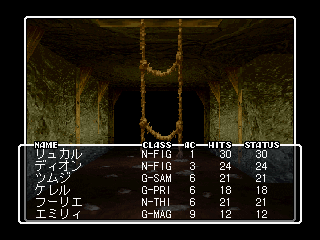

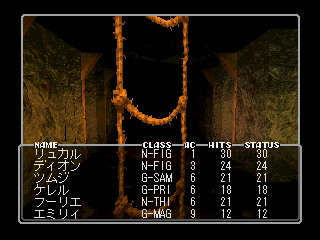

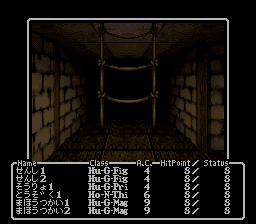

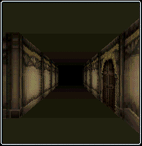

Comparison Screenshots: Dungeon View

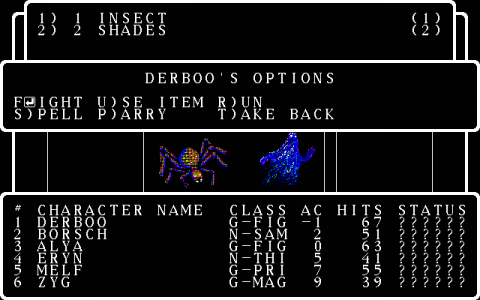

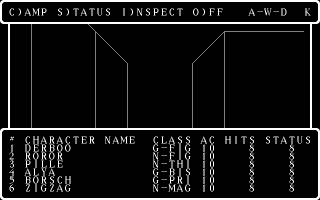

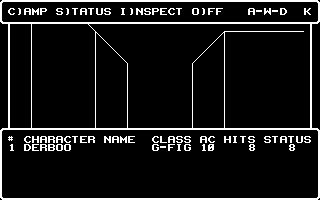

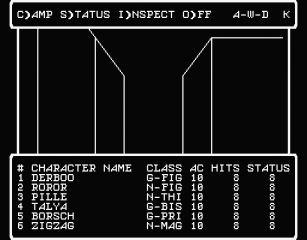

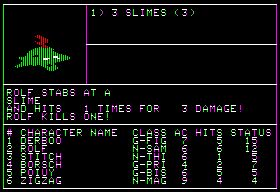

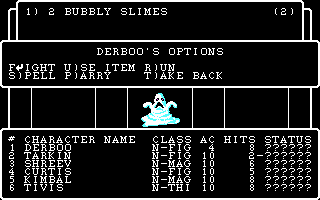

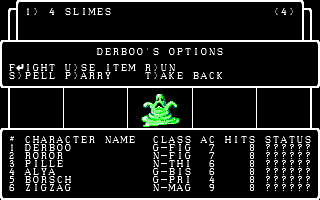

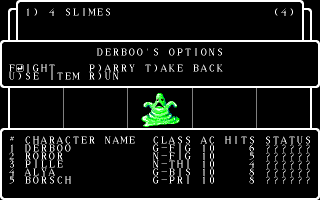

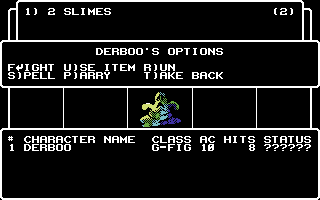

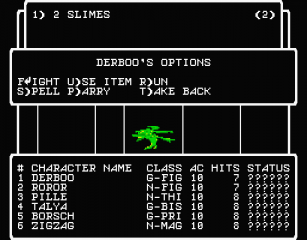

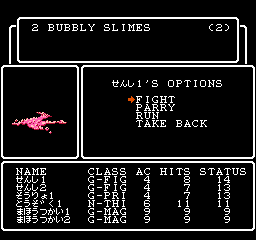

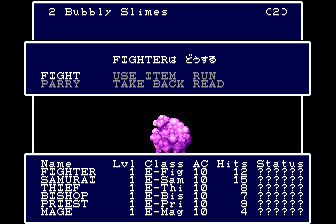

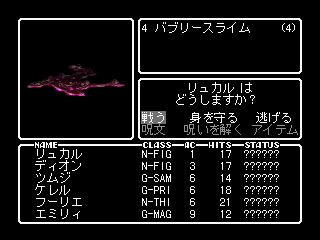

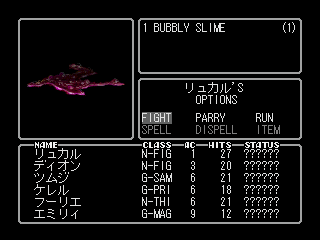

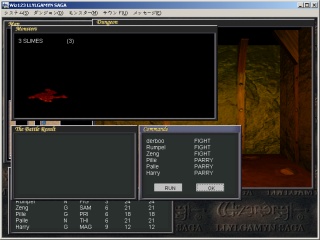

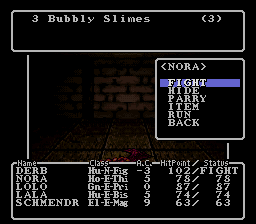

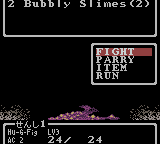

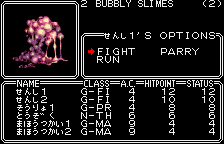

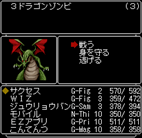

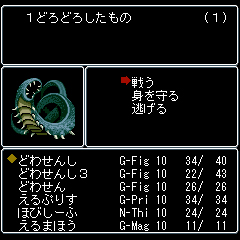

Comparison Screenshots: Battle Screen