- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

Mobile Games

Besides several ports of the Lllylgamyn trilogy, Success thoroughly exploited their license to bring many original scenarios to Japanese mobile phones. This started in 2002 with a line called Monthly Wizardry. Despite the name, there seem to be only two scenarios for this, “Melancholy of the Young King” and “Intruders of the Annedale Forest”. Even if the latter title seems to promis outdoor areas, the games just use the good old wireframe dungeons, although the walls are at least filled out with color. Wizardry Traditional from 2004 runs on a very similar engine. Once again there are two scenarios, “Twelve of a Kind” and “Grace of the Moonspoon”. In between the two series, Success also published a more graphically impressive game labeled DoCoMo Wizardry, after the service it was released on. Like many Japanese companies that had touched Wizardry, Success ended up publishing an inspired original IP as well. The Dark Spire features refreshingly stylized graphics, including the option to switch to the Wizardry-typical vector lines. Success even offers a dungeon map plotting sheet, like Sir-Tech packed with the early Wizardry games, for download on the game’s official homepage.

Not by Success, but by So-Net was Wizardry Online Mobile, which was released in 2010 and obviously a lead-in for the big online game from a year later. Like its Windows counterpart, it also does away with the first person dungeon crawling, here in favor of an isometric view.

In 2013, Bandai Namco Games published a Wizardry game with the subtitle Senran no Matō (戦乱の魔塔; appears on the English App Store as Tower of the Maelstorm, sic!) to the iOS and Android marketplaces. It looks to go back to the traditional first person dungeon crawling, but seems riddled with free to play systems. Gamepot’s iOS exclusive Wizardry Schema was launched the following year, and somehow someone decided that what Wizardry really needed to drop was the dungeon crawling. It doesn’t replace it with anything, either. The “players” just create and equip their party, then they can read a summary of their adventures every once in a while and buy new stuff and manage their level-ups in between.

Other Media

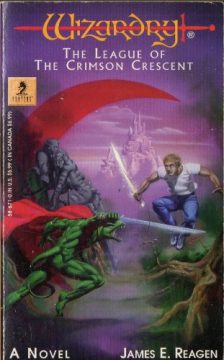

In the era when Wizardry was big in North America, North America still wasn’t so big on cross media tie-ins for computer role-playing games. The only product along that line was the odd novel The League of the Crimson Crescent, whose premise about a normal world dude entering a fantasy world and becoming a legendary hero there seems rather reminiscent of Ultima.

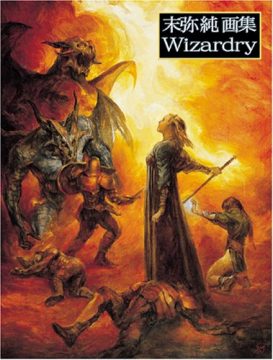

In Japan, on the other hand, the licensing machinery ran at full steam almost from the very beginning. There were two series of manga by Tamaki Ishigaki, which started in 1988 and ran over 9 volumes in total. Another important name at that time was Penii Matsuyama, who was involved in further mangas, novels and strategy guides, of which there were several for each game. There were “Guidebooks” and “Handbooks” and “Playing Manuals” and “Monster Manuals” and “Perfect Manuals” – if Japanese bookstores had desired to set up an entire Wizardry section, they wouldn’t have had any lack of material to fill it. With the “Wizardry Rennaissance”, the mangas also came back in 2010, in form of four volumes called Wizardry Zeo. Jun Suemi, monster designer for the Japanese editions, also published a Wizardry artbook full of moody fantasy illustrations, some of which appeared on the covers of the PlayStation compilations.

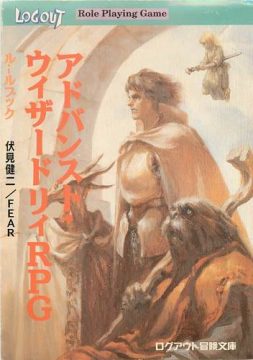

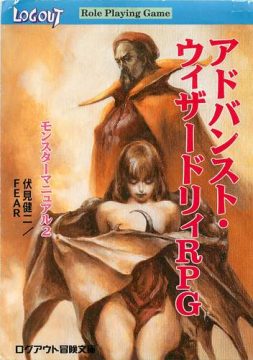

No doubt the oddest step to take for Wizardry in Japan was going back to a pen and paper role-playing system – after all, the series more or less ran on simplified Dungeons & Dragons rules to begin with. The Wizardry Role-Playing Game was first published in 1988, followed by several supplemental books and a revised version called Shin Wizardry RPG (“True Wizardry RPG”). Even later, in 1995, there was the Advanced Wizardry RPG, which was built on the rules and world view of Bane of the Cosmic Forge. To those who desired a lighter “RPG” experience, there were also three Wizardry volumes in the Famicom Bōken Game Book series, plus one Game Boy Bōken Game Book for Wizardry Gaiden. Fitting figurines of Wizardry monsters for tabletop play were already sold even before the official Wizardry RPG was released.

It wasn’t all just books, though. A Wizardry anime, based on Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord, was also released in 1991. It tells the story of the ninja Hawkwind, the fighter mage Alex and the warrior Shin, who make a living by fighting monsters and hunting treasure inside the dungeon. The plot thickens when they meet the wizard Joeza and his comic relief hobbit pupil Albert. Joeza has been a former companion of Werdna before he turned evil, and has sworn to defeat the traitor and take back King Trebor’s amulet. Werdna of course plans to use the amulet to break a thousand year old seal and doom the world forever. Deep inside dungeon, they also help out an elven woman, to complete the party of six, and to make sure everyone gets that this anime would rather be Record of Lodoss War.

On the other hand, the movie follows the game a bit too literally – it’s a world full of adventurers, who keep going into the dungeon and raising treasure as a day-to-day job. The heroes get to the lower dungeon levels with an elevator, which they activate by holding up a ribbon, just like in the game. The characters are always talking about how Werdna is sitting in level 10 of the dungeon, and that’s indeed where he is. Monsters are referred to by their English names, and it’s weird to have characters phonetically proclaim the arrival of a “Greater Demon” as if it was an exotic name, instead of just using the Japanese equivalent.

It’s also quite violent – monsters and humans alike get hacked into pieces en masse, and the party stumbles upon the horribly mutilated corpses of less fortunate adventurers. The action is decent – even if the director doesn’t have a clue what to do with so many heroes, and in any given battle scene, most of them just stand around off screen.

The writing, however, is ridiculous. Case in point, when learning that a female adventurer has gone into the dungeon, her group obliterated, Alex states: “Maybe she’s lying around here somewhere – naked.” Turns out she is alive and kicking (and fully clothed), though, and her reply when asked for her name: “Sheer. All my friends got killed.” The whole thing is just so rushed, too much pressure to solve an epic quest in no more than 50 minutes running time. After completing the mandatory party of six, amazingly the elven lady is never turned into a damsel in distress. In fact, it’s her who gets to take down all of the big villains short of Werdna himself, but those moments of badassery are hardly enough to elevate the anime to must-see status.

Additional Anime Screenshots

Various Book Covers