- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

Once upon a time, a game called Wizardry, created by Robert J. Woodhead and Andrew C. Greenberg and published by Sir-Tech, used to be the biggest name in home computer gaming. Together with the Ultima series, it shaped the outline of an entire genre for decades to come. Although vaguely based on a couple of mainframe games and of course Dungeons & Dragons, it popularized first person dungeon crawlers on home computers, a special breed of fantasy role-playing games that remained strong well into the 1990s. Wizardry wasn’t the first commercial home computer RPG – Automated Simulations’ Temple of Apshai predates it, as do Akalabeth and – if only by a margin – the first Ultima (and all that’s even after more obscure, DIY scope publications like Devil’s Dungeon, Beneath Apple Manor or Space I).

Its party-based combat and immense attention to detail, however, left critics and gamers alike puzzled how Woodhead and Greenberg managed to cramp such a rich experience into the very limited space of only two floppy disk sides, and made sure it would overshadow its competitors. The very first Wizardry title was voted the most popular Apple computer game of all time by the readers of Softline magazine in spring 1984, and also remained a constant leader in the popularity polls by Computer Gaming World, until the groundbreaking Ultima IVand the “first RPG for the layman,” The Bard’s Tale, finally managed to dethrone it in 1985. At that point, Wizardrywas so important that the new kid on the block even included the option to import its player characters.

The Wizardry series started to peter out a bit at that point, but its initial influence could still be felt in many games that followed it. Whether they added surface exploration like Might and Magic and the aforementioned The Bard’s Tale, or real time combat and state-of-the-art graphics like Dungeon Master and Eye of the Beholder, they all were indebted to Wizardry. This even extended to many early European RPGs (though mostly through the conduit of The Bard’s Tale and Might and Magic), be it Silmarils’ Ishar trilogy or Spirit of Adventure and the Realms of Arkania series by Attic. The latter eventually came full circle when it was localized by Wizardry publisher Sir-Tech for release in the US.

David W. Bradley spectacularly reinvented the series in the early 1990s, but he couldn’t prevent the big slump for traditional CRPGs in the West that soon followed, which led to the temporary demise of all the big name series. Although Wizardry in a way went out with even two swansongs in the early 2000s – a legitimate one by Sir-Tech, and a spiritual successor by Bradley and his new company Heuristic Park – neither of the two was able to restore the glory of old.

But the Wizardry phenomenon only unfolded its true potential when it traveled to the other side of the world. Although both Wizardry and Ultima weren’t officially introduced to Japan until late in 1985, they certainly had gathered a dedicated insider following well before that date. Roe R. Adams III wrote in his column “Come Cast A Spell With Me” in Computer Gaming World from September/October 1985, though probably not without hyperbole:

Both Wizardry and Ultima have huge followings in Japan. The computer game magazines cover Lord British (Ultima) like our National Inquirer would cover a television star. When Robert Woodhead, of Wizardry fame, was recently in Japan he was practically mobbed by autograph seekers. Just introducing himself in a computer store would start a near stampede as people would run outside shout that he was inside! (sic)

First role-playing games with obvious inspirations by the two giants had already started infiltrating the archipelago. But the greatest result of Wizardry’s impact wasn’t the waves of dungeon crawlers that since started to inhabit Japanese home computers, but a new amalgam that became known to later generations as the JRPG genre. Two young Enix programmers and Wizardry fans named Koichi Nakamura and Yuuji Horii – who first met their new favourite game at a trip they won in an Enix programming contest, to visit the 1983 Applefest held in San Fransisco during October 28-30 – took the overhead world exploration of Ultima and paired it with Wizardry’s menu based combat to create Dragon Quest (possibly with some hints of earlier Japanese RPGs) and the rest is all history now.

But helping to fuel the igniting spark for the Japanese RPG tradition wasn’t the final extent of Wizardry’s influence, as the brand itself stayed popular in Japan over all those years, even after it was all but forgotten in its home hemisphere. Ever since the first ports of Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord appeared on Japanese home computers, the first and so far only year that didn’t see any official Wizardry game releases was 2008, but immediately following that brief drought, the series experienced yet another resurgence thanks to the Acquire-initiated Wizardry Rennaissance project. This makes Wizardry by far the longest running computer RPG franchise, with the total number of released titles and ports putting to shame any other RPG series out there.

The road to Wizardry

It all started very small, merged from the hobby projects of two students at Cornell University. Robert J. Woodhead, at the time a student at the psychology department, entered the gaming scene when he uploaded a program with the file name “sorcery” onto PLATO. Apparently the game was based on the code of another dungeon crawl, dnd (1975), already showing some of the whimsical traits Wizardry should later become known for. Elven boots, so the dnd manual reads, were replaced with socks. The dnd authors didn’t took too kindly to the rip-off (disregarding the fact that their own program was an unlicensed adaption of Dungeons & Dragons, which the title didn’t even try to hide) and made sure that “sorcery” was deleted.

Soon Woodhead shifted his programming efforts to the Apple II, and he found new partners to publicize the results. Like Robert Woodhead, the Sirotek clan lived in Ogdensburg, New York after migrating from Czechoslovakia through Canada. They came first into contact when Woodhead’s mother became involved with the patriarch Frederick Sirotek, Jr. to cooperate with her resin sand business. Woodhead’s first program was a software to speed up the enterprise’s shipping calculations. Soon afterwards he developed the mail order application Infotree, which should become the first product published by the new company Sirotech, led by Fred’s sons Robert and Norman and intended by their father as a means of practical education. After a huge success showcasing the software at the Trenton Computer Show, Woodhead and his driver Norman already made plans for further cooperation on the ride home – the tactical space warfare game Galactic Attack was conceived. Released in 1980 (first introduced in Softalk Volume 1), it was the last software to bear the Sirotech label, before the company changed names to a less obvious variant of the pun, Sir-Tech.

The mad minds that created Wizardry – Greenberg (left) and Woodhead in Softalk Magazine August 1982

Andrew C. Greenberg’s background is told more briefly: As the first issue of the fan newsletter Wizinews tells, he started working on his own computer variant of the Dungeons & Dragons formula in 1978. The name of the game: Wizardry. Coded in BASIC, it was in a playable state in fall 1979 at latest, as by then it had become popular among Greenberg’s fellow students. According to Softline (Vol.1 No.4), the two finally met in June 1980. Robert Woodhead was planning to create the fantasy role-playing game “Paladin” for Sir-Tech, and remembered hearing about Greenberg and his Wizardry, which he came to regard the superior game to his own attempt. Not content with the performance of the BASIC code, Woodhead would rewrite the game from scratch in PASCAL, while both kept refining and adding to Greenberg’s concept, taking inspiration from what was available on PLATO at the time. Back in the day when Wizardry was received as the hot new thing, Sir-Tech kept quiet about the PLATO influence, but Woodhead remembered much later:

Both Andy and I were active on the PLATO system, which was a tremendous influence on us. […] The multiplayer dungeon games were particularly good. Pretty much all of the basic concepts of multiplayer gaming were developed there. Wizardry was in many ways our attempt to see if we could write a single-player game as cool as the PLATO dungeon games and cram it into a tiny machine like the Apple II.

Commenters often place emphasis on Oubliette (1977) as the definite influence, although shares of credit most likely also need to go to Moria (1978?) and avatar (1979), the latter of which first introduced the menu-based town (in Oubliette and Moria the cities are mazes almost as convoluted as the dungeon itself). But Greenberg and Woodhead weren’t content with copying existing games. The PLATO dungeons are much larger than the Wizardry scenario, but feel empty and generic. The Wizardry creators felt that something was lacking. As Woodhead explains in High Score! The Illustrated History of Video Games: “We added a concept and story line to what we’d seen on PLATO, where it was ‘hack-hack-kill-kill-occasionally something interesting happens-run away…'”

Following the narrative of that book, the Greenberg-Woodhead cooperation wasn’t the most harmonic one in the beginning. Before they even met in person, Woodhead got frequently kicked from PLATO for his constant game programming and playing by Greenberg, whose job at the time was to operate the system at Cornell. He said about his would-be partner: “He was one of those people who just seemed to live to make my life miserable.” The bad grades Woodhead’s conduct earned him eventually got him expelled from university for a year, which gave him ample time for coding games. Supposedly the two argued a lot during the development of the first Wizardry scenario, which might have been the origin for the antagonist roles they took in the game: Werdna (Andrew spelled backwards) became the evil wizard the party was sent out to destroy by the mad overlord Trebor (you know the deal).

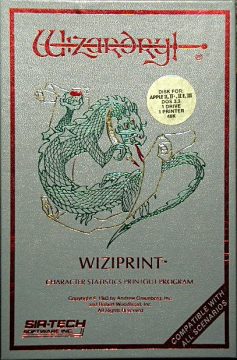

At the height of Wizardry’s popularity, Sir-Tech

could do whatever they wanted – like selling the program to print out character sheets separately.

Despite – or maybe thanks to – the rivalry, Wizardry was soon shaping up and Sir-Tech first presented it to the public at the New York Computer Show in November 1980. At that time the game was still slow and plagued by lots of bugs, and the creators insisted on waiting until Apple would release a runtime system for their computers before they started selling it, so it could be run without the need of additional PASCAL language systems.

Early copies were finally sold at the 1981 Applefest (June 6-7, and thus vaguely at the same time as the commercial release of Ultima) with the subtitle Dungeons of Despair, in what was likely the first early access model in commercial video gaming. It’s easy to imagine how Gary Gygax and TSR wouldn’t have taken too kindly to the double-D moniker, and indeed the father of modern fantasy role-playing games contacted Sir-Tech about his legal concerns, but no actual litigations ever took place. At any rate, the title went, the game stayed. After many further tweaks resulting from feedback of Dungeons of Despair customers, Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord was released late in September 1981, and it massively contributed to shaping the landscape of computer gaming for the years to come.

Links:

TK241 Repository for hints, maps and instructions for the original series.

Wizardry Fan Page by Snafaru Particularly valuable for scans of old documents like Wizinews.

Boltac’s Trading Post Huge Japanese fansite.

Museum of Computer Adventure Game History Photos of boxes and other documents of many classic computer games.

Gamespot – Q&A: Wizardry 8 Interview with Ian Curie.

Gamespot – Wizardry 8 Q&A Interview with Linda Curie.

Matt Chat – Interview with Brenda Romero 1 2 3 4 5 Great talk about her career that started with the Wizardry hotline.

Matt Chat – Interview with Robert Sirotek 1 2 3 4 5 Tracing back Sir-Tech’s company history with one of the founders.

Matt Chat – Interview with Robert Woodhead 1 2 3 Chatting with the programmer of the original games.

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview Another Interview with Robert Woodhead on Wizardry.

Print Sources:

Popular Mechanics April 1981 – Computer Wizardry One of the earliest published previews of Wizardry.

Softline March 1982 – The Wonderful Wizard of Odgensburg: An Interview with Robert Woodhead 2 3.

Softalk August 1982 – Exec Sir-Tech: Wizzing to the Top 2 3 4 Early company profile.

Wizinews #1 – Casting the Spell 2 3 A making of with rare insight into Greenberg’s perspective.

Quest Busters January 1986 – Wizardry Info on Macintosh Wizardry by one of the beta testers.

Quest Busters March 1987 – Interview: Wizardry’s Robert Woodhead 2 Covering Wizardry IV, V and the VM.

Computer Gaming World December 1992 – Company Report: Sir Tech 2 3 Another company profile.

Computer Gaming World October 1998 – Wizardry 8 2 3 Preview.

Wizardry did it!

To demonstrate the tremendous influence Wizardry had on (J)RPGs, here is a list of elements either introduced or popularized by Wizardry, without which the history of the genre would be looking quite differently. Some where actually inspired by the PLATO dungeon crawls, but are nonetheless included in this list because those existed in a very different – and somewhat hermetic, in comparison – environment.

Party Gameplay

In the mainframe games, adventurers either had to go out on their own or team up with other players in a group, but everyone would still just play one single character to command in combat. Only the party leader had control over movement through the dungeon, which resulted in a rather dull experience for everyone else. Even Ultima was a solo journey until the third iteration, and it is certainly no coincidence that only then market shares started shifting in Lord British’s favor. Turn-based RPGs and party management just go together like bread and butter, and Wizardry showed that to the world.

The Slime

Yes, Dungeons & Dragons does have slime and goo creatures, and Wizardry of course took them from there. Its typical role, however, as the weakest and most basic enemy in Dragon Quest and many following JRPGs, the blob got from Wizardry (in Western RPG tradition, that role usually falls to rats). As Yuji Horii remembers: “I was really hooked on ‘Wizardy,’ the PC game, and that’s kind of where I got the inspiration for the Slime. […] I was doodling the slime-looking character and I took it to Mr. Toriyama, who did the character design, and he made it the Slime we see today.”

Separate Battle Screen

Ultima’s monsters were roaming freely through the dungeons from the very beginning, whereas all the PLATO dungeon crawlers would just project them into the 3D view. Wizardry eventually adopted the latter approach as well, but the “damage” was done.

Job Changes

No, Final Fantasy III wasn’t the first to apply the concept (which already existed in Dungeons & Dragons) to digital RPGs. Heroes in Wizardry are able to change their class whenever their base stats allow it, retaining some of the advantages they’ve earned with their former profession. Some of them, like the Lord and Ninja, are even impossible to get from the very beginning, effectively making them prestige classes.

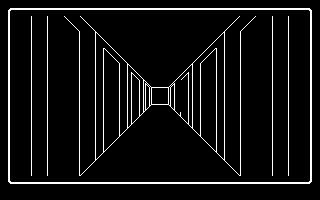

Windows

You like the opaque, mostly black or blue windows with the rounded white borders that used to be omnipresent in JRPGs for over a decade and aren’t quite gone even today? You can thank Robert J. Woodhead for that, too. Legacy of Llylgamyn introduced them to the Apple II in 1983, and they stuck with almost every port and sequel ever since. The craziest use of the Windows can be found in the first Final Fantasy, which even keeps the player characters in a different window than the monsters they’re facing.

Systematic Spell Words

Wizardry‘s magic system relies on a fixed pool of spells, but unlike Dungeons & Dragons, their names are set up as if to hint at a greater logic behind them. BADIOS is the attack variant of the healing spell DIOS, HALITO for fire attacks has stronger versions called MAHALITO ad LAHALITO, related to the MELITO and MOLITO sparks. It seems this feature was borrowed from the PLATO game Oubliette – some of the spell names are even the exact same (although since PLATO games were edited continuously, it’s hard to track when those were put in). Wizardrymay not have been the inventor, but it certainly was the mediator who introduced it to a large audience beyond university mainframes. Final Fantasy has played upon this with couplings like FIRE / FIRA / FIRAGA, but it was the obscure Squaresoft game Rudra no Hihou (fan translation pictured) that took the concept one step further and allowed players to compose their own spells.

Character Generations

This was one of the bullet point features for Phantasy Star III and Fire Emblem IV. Whereas those two examples explore the narrative implications more closely than the mechanical application, the appropriately titled Legacy of Llylgamyn first used a feature like that: characters are imported from the previous scenario, but instead of taking them over directly, the data is used to generate their descendants.

Multiple Endings

Arcade games had known hidden “true” endings for a few years, and there were some adventure games with different outcomes, but among RPGs, fundamentally different endings were first introduced in Return of Werdna with five different ways to end the game (besides just dying). Wizardry VII even features multiple beginnings, which depend on whether or not a save from Wizardry VI is imported, and which ending was achieved in the former game.

Monster Recruits

Now this is a curious case. Recruiting demons to the party to make them fight for the main heroes is a major element in the Megami Tensei series, just as Werdna has to rely on them to escape from his “grave” in Wizardry IV. The only problem in drawing a connection: The Japanese game was actually released a month before the American one (with an official Japanese release for Wizardry IV coming much later). However, the general concept of Wizardry IV was publicly known at least since early 1985, but it is uncertain whether the news had reached Japan. It may have been all just coincidence, yet the conceptual similarity is definitely uncanny.

Summon Spells

Two of the spells Wizardry V added to the mix summoned monsters or elementals to aid the party in battle. One-and-a-half year later the same kind of spell made its introduction in Final Fantasy III, and became a staple in the series afterwards. The impressive presentation was still missing in Wizardry, though, where the helpers’ representation is no more than a text window with their names and numbers. At least they stuck around for the duration of the fight, a feature Final Fantasy didn’t see until more than a decade later.

Locks & Traps Mini Games

For once this is a tradition that lives on mostly in Western games, be it Mass Effect, Fallout 3 or Bioshock. While the first mini game in an RPG is likely the spaceflight scene in Ultima I, Bane of the Cosmic Forge introduces short challenges for the standard procedures of picking locks and disarming traps. Hacking computers in sci-fi themed games like Mass Effect 2 (pictured) is just a natural extension of the concept.

Diplomacy

Earlier RPGs featured some simple implementations of reputation and changes in NPCs’ attitudes – like city guards that would attack criminal players. Wizardry VII, however, has a complex system of alliances, where actions towards one character could have repercussions regarding their friends, or even entire factions. It really seems as if Japanese RPG developers were done learning from the US, as once again it became a mostly exclusive Western trend later after Interplay launched Fallout, and it has seen many (often simplified, sometimes expanded) variations in RPGs by Black Isle, Bioware, Troika and Obsidian since.