- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

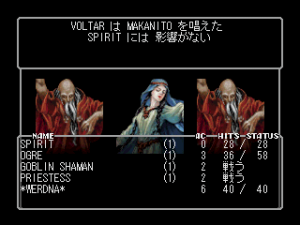

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

Some of the Apple II version screenshots were taken from Let’s Play Archive.

Wizardry was an excellent game in its time, but the series rested on its success for a bit long. While Richard Garriott invented Ultima anew with every new episode, the second and third releases were little more than expansions for essentially the same game. That should change drastically with Return of Werdna, one of the strangest RPGs of its time, and one of the hardest RPGs of all time.

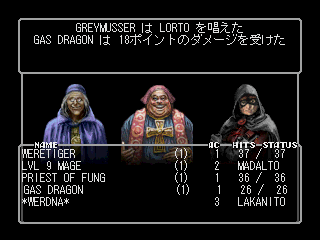

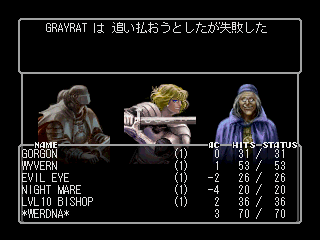

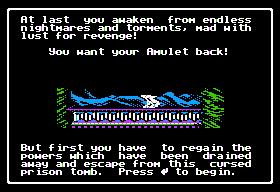

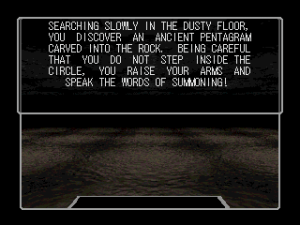

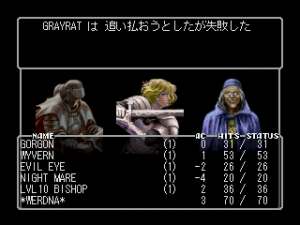

Instead of importing or creating another band of adventurers, players were cast in the role of the evil wizard from the first game, who starts out imprisoned in a deep underground labyrinth. The goal is to regain his sealed powers, and make it back to the surface through countless waves of “do-gooders”. Werdna doesn’t have to stay on his own, though: Throughout the maze are laid out pentagrams, where he can summon his usual mooks and beasts.

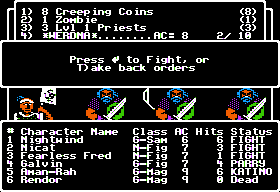

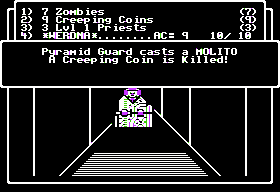

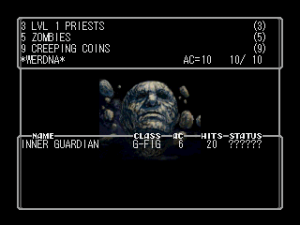

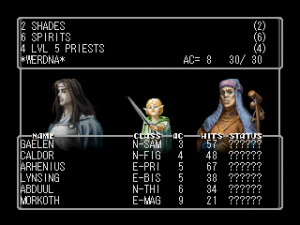

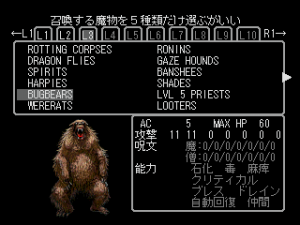

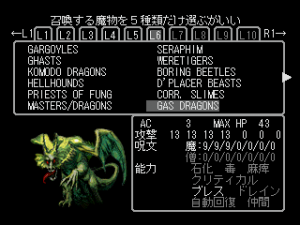

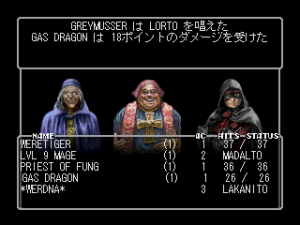

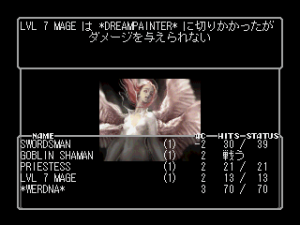

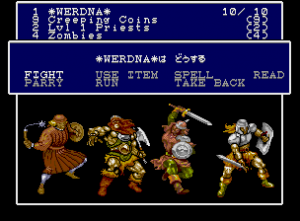

The underlings aren’t commanded directly, though, bringing combat in the fourth Wizardry scenario closer to a strategy game than an RPG. Knowledge of their strength and weaknesses from previous Wizardry games was essential to stand a chance: Creeping coins for example do only 1 point of damage per attack, but can breath of the entire party of do-gooders. They are also strong in numbers and can call reinforcements, so it can take enemies a while to punch through them, providing much protection to Weirdna.

This isn’t limited to combat, but also extends itself to the often super obfuscate puzzles. Right in the beginning, Werdna finds himself in a tiny room with no doors in sight. Only if he hires a group of (evil) priests and one of them randomly casts the light spell “MILWA” in combat, the hidden exit becomes visible. The only way to know that priests casts MILWA is by having played the previous Wizardry titles, and the spell didn’t even have that effect there. Of course there’s nothing in the game or manual to inform players about this, and it’s even possible to go through a lot of battles with the priests without them casting the spell. Two stories up, and Werdna has to maneuver his way through a minefield – only there is no way to figure out which spaces are safe, and players have to find the exact path on the huge map by trial and error. And this is only the beginning!

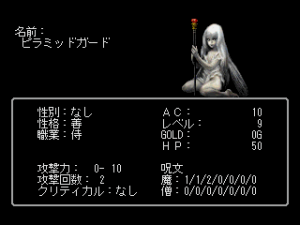

Throughout the game, Werdna remains the only character who can be managed and commanded directly, who can wear equipment, use items, and level up. The latter doesn’t happen the usual way through accumulating experience points, though, but instead reaching a new dungeon floor comes with an upgrade each time, enabling Werdna to cast spells of a higher level and unlocking a new tier of monsters at the pentagrams.

Aside from the various adventurers to fight, there is a number of one-time guardians who are fixed in place, and the ghost of the mad overlord Trebor – who died of paranoia after he got his hands on Werdna’s mighty amulet – haunts the premises, and if the evil wizard doesn’t stay on his toes, an encounter with him always ends deadly, so in a way this game is also survivor horror. All the player ever hears (or reads) of his nemesis are his ghastly mumblings like “W…E…R…D…N…A…” or “I…COME…FOR…YOU…”, as he draws nearer and nearer. In the original version, he even moved around in real time, although in later ports his movements are triggered per keyboard input. If he gets too close, only saving the game – at least The Return of Werdna was the first Wizardrytitle to allow it manually – can reset his position, but this comes with a serious caveat: Roaming do-gooders on each dungeon floor are finite in number, but whenever the game is saved, they all respawn.

Even though it is hard enough to complete the game even once, The Return of Werdna is also the first RPG to feature multiple endings, five of them precisely. One of them was so hard to achieve that it was rewarded with the title “Wizardry Grandmaster Adventurer”. Sir-Tech discouraged magazines and players from revealing it to others, and the ending triggered a message to call Sir-Tech and tell them about the achievement. But the steps to reach it are so complex and obscure, the fact that it was discovered at all is a testament to how much time and undivided attention people had to spend on a single game in the ’80s.

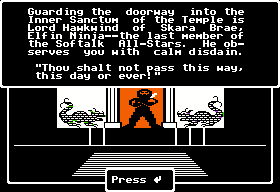

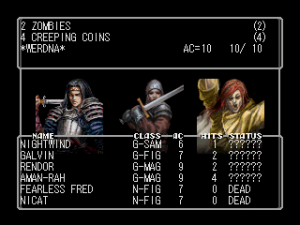

The Return of Werdna was designed by Roe R. Adams III, who had already written the manuals for previous Wizardry games. He was kind of an omnipresent figure in the early CRPG scene, because not only did he use to write RPG columns in several computer magazines, he is also the only one who had worked on three of the big RPG series of the 1980s – Ultima, Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale. It seems to be to his credit that all three game worlds contain a city called Skara Brae. It was certainly his doing to also implant his RPG alter ego Hawkwind, leader of the Softalk All-Stars, first introduced by Adams as an example band of Wizardry adventurers in Softline magazine in March 1982, and the canonical party to defeat Werdna in the first game. The elven ninja Hawkwind is the penultimate opponent on Werdna’s road to victory, but he is not the only “real” hero: All of the do-gooders in the dungeon are supposedly named after characters by actual players of the previous games, who had sent in their disk to Sir-Tech’s support to fix. It must have blown the minds of many Wizardry fans of the first hour when they ended up fighting their own alter egos from past adventures.

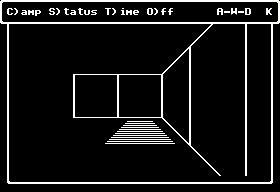

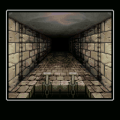

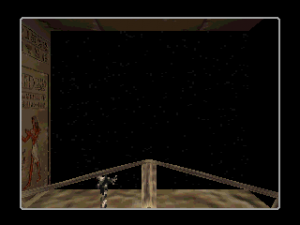

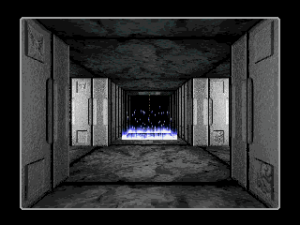

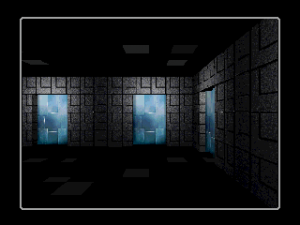

Wizardry IV had one problem, though: It never seemed to get done. The fan newsletter Wizinews was already looking forward for a release in late 1984, and by the following year the overall concept for the game was made public. Yet it took Woodhead and Adams until 1987 to get all the fine-tuning done. Retaining the stark wireframe dungeons of its predecessors, the game of course looked hopelessly outdated compared to newcomers like The Bard’s Tale and Might and Magic, which already featured detailed environments.

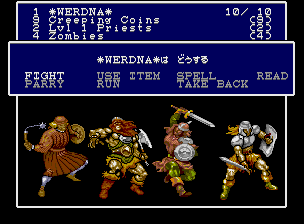

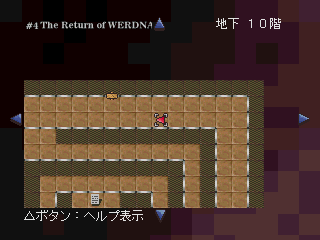

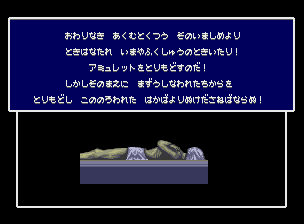

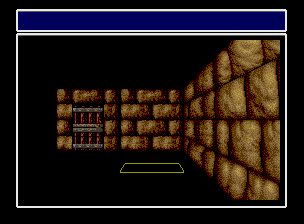

Both the late release and brutal difficulty certainly put a dent in Wizardry IV‘s popularity – accorting to Robert Sirotek, it was the worst-selling product in the entire history of Sir-Tech. That may also explain why it was ported to much fewer platforms than the other games. Especially console players didn’t get to see much of it, as the NES line was discontinued and both the Commodore 64 and SNES skipped it in favor of the following episode. Initially the only way to play it on a console was the PC Engine CD, which was oddly bundled with Legacy of Llylgamyn. It looks very much like the rest of the games on the platform. Addressing the insane difficulty of the original, it was much simplified: Some puzzles are omitted, including the introductory one, so Werdna can simply step out of his inner cell without any resistance. This version also allows to command the monsters directly, though not as minutely as the heroes in the earlier games. It’s possible to choose whether monsters attack or use a spell, but not which one to cast.

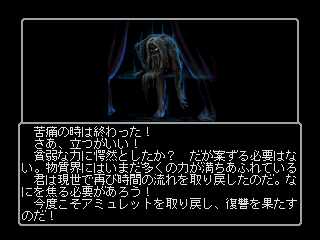

Later, the game appeared on New Age of Llylgamyn for PlayStation and Windows PCs, this time bundled together with Wizardry V. This version features the original game alongside an arranged mode that – similarly to the PC Engine version – makes it possible to control the monsters, but is made even more involved by increasing Werdna’s entourage to five monster groups instead of three and allowing direct selection of their spells. Overall, monsters are rather treated as individual characters, who have individual hit points and can be healed. This completely mixes up the balance, as monsters who justified their existence through strength in numbers have become mostly useless. It also adds a few additional monster types per circle, offering abilities that are completely absent in the original game. At any rate, the fights aren’t much easier for it and it’s still easy to get slaughtered at any time.

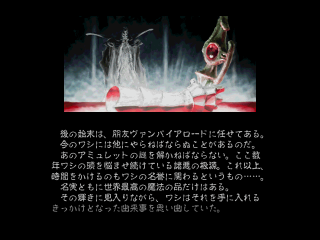

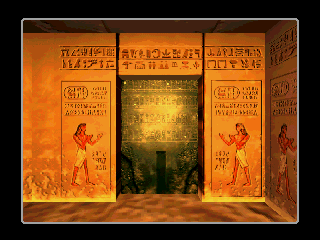

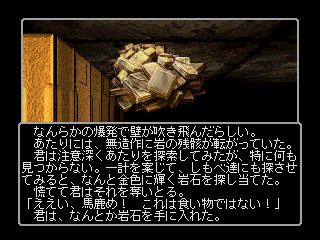

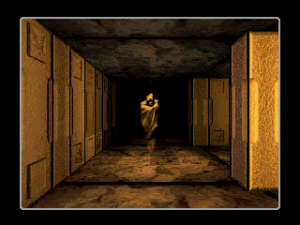

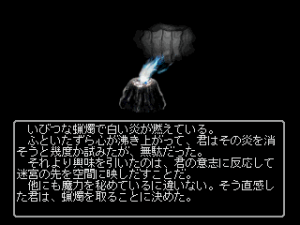

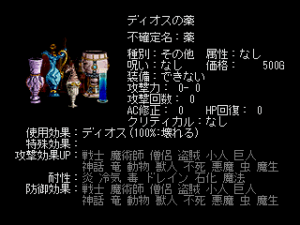

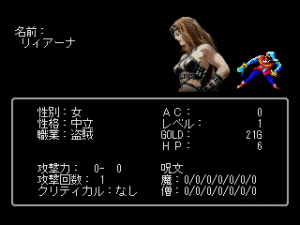

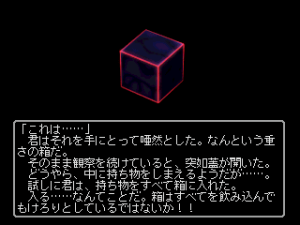

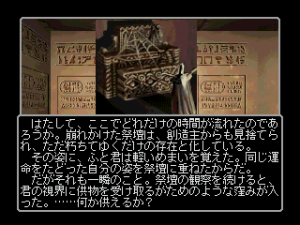

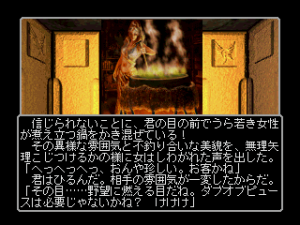

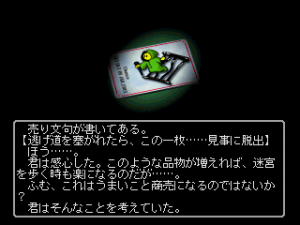

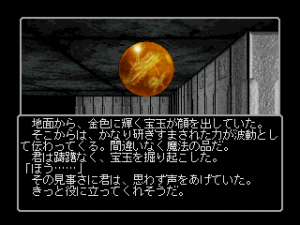

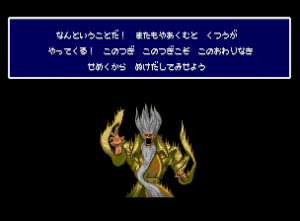

What definitely does make Werdna’s life easier is the revised black box – in the original, it extends the inventory by 19 slots, but is rather tiresome to manage as items have to be put in and pulled out again all the time. In the arranged game, it completely replaces the standard inventory, sorts the items in handy categories, offers limitless storage and provides detailed illustrations for easier recognition. Like in the Llylgamyn Saga, an automap is freely accessible for both variants. Separately switching between the new and old graphics for monster sprites and dungeon walls is possible in both original and arrange modes, but only the latter features added illustrations for events and different (but still mostly abstract) visual representations in the dungeon where merely a rectangle on the floor used to indicate special locations.

Unfortunately, the arranged version has a lot of extended text that cannot be switched to English – only the names for items, monsters and do-gooders are available in both languages. As Werdna makes his way through the maze, info on all the items and adventurers he encounters gets unlocked, and a database can then be accessed from the main menu.

PlayStation Intro

Comparison Screenshots