- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

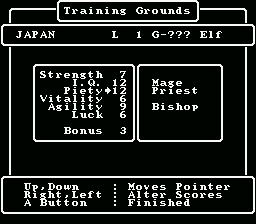

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

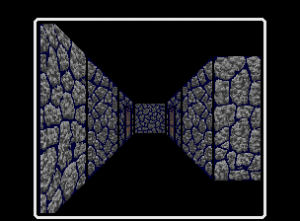

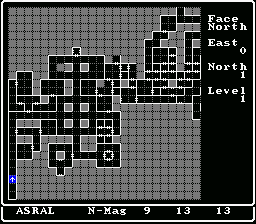

After The Return of Werdna, Robert Woodhead moved on to other enterprises, so Sir-Tech brought in a new programmer and co-designer on board: The soon-to-be legendary D.W. Bradley. He originally pitched his concept under the name “Dragon’s Breath” and apparently had started a program from scratch, but Sir-Tech convinced him to transplant the concept into the Wizardry system. Despite its origin from outside, the resulting Wizardry V doesn’t stray too far from its roots, but Bradley introduced a lot of small tweaks and thoroughly updated the old engine, freeing the series from many of its inherited liabilities. For one, the dungeon levels are no more confined to a 20×20 tiles grid. Not only are they much larger, but also structured more naturally. There are no wrap-around dungeons left, either.

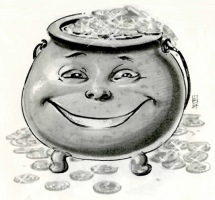

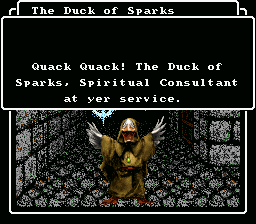

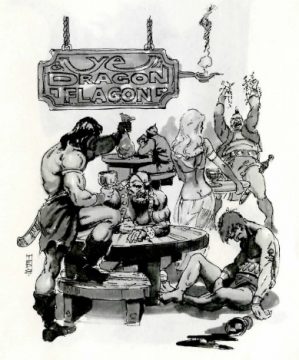

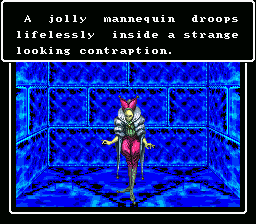

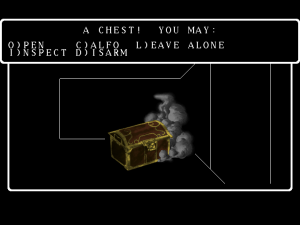

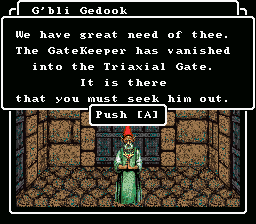

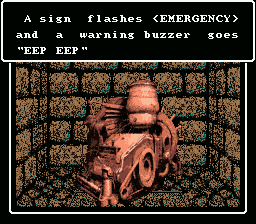

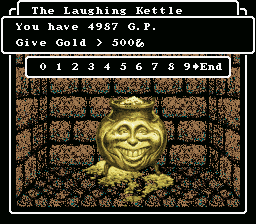

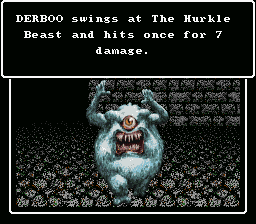

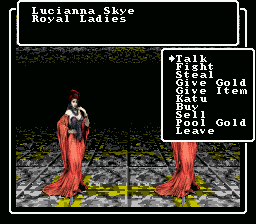

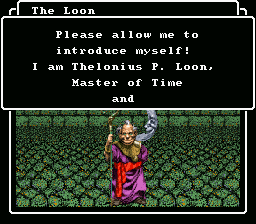

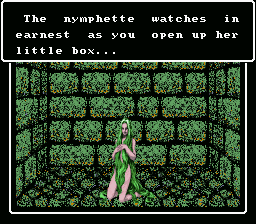

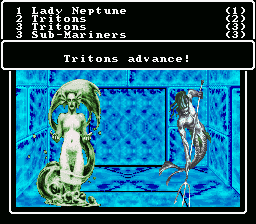

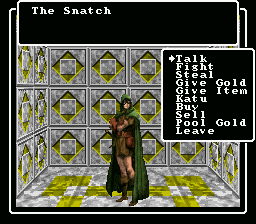

But the dungeons are not only expanded in size, but also in content. There’s a ton of riddles and puzzles, and strange encounters with the inhabitants of the depths. For the first time in a Wizardry game, there are actually NPCs to interact with in detail. An adventurer can talk to them for information by typing in keywords, buy or sell, or hand them key items. Less trustworthy parties can even steal from them or attack, but many of them are quite strong. Some of them are necessary to complete the quest, so they can be resurrected at the temple in town afterwards. They also might be rather grumpy at the next meeting, but fortunately it’s possible to charm them with a spell or bribe them with gold. The dungeon dwellers are a rather goofy lot: They include a laughing kettle who gives cryptic hints for gold, drunk dwarves that constantly ask the adventurers to buy them booze, or a prince who was turned into a monster and cursed with itching feet by his arch-nemesis, condemning him to keep hopping around the dungeon floors in search for relief. Since many of the puzzles rely on trading and using items – and some of those have to be kept around as keys – the party always operates on tight inventory space. Quest items always come as unknown and need to be identified to use them, too, so a bishop in the group is even more indispensable than before.

Another class that got its value boosted are the thieves. Wizardry V was the first game to introduce the option to hide in shadows and launch vicious ambush attacks from the back. This finally makes them useful in combat, even though in the computer versions the success rate is still very low, and the thief has to try and hide again after each attack. There are also a lot of locked doors that need to be unlocked by a thief at a sufficient experience level, although like disarming traps, the job can also be done with a spell. The traps all have new names, but that doesn’t change anything in the way to deal with them.

Not tied to the thief class, even though they technically fall into the same skill set, are the options to search for hidden items and secret doors. This can be done at any place in the dungeon, and only affects the currently occupied tile. That means finding secret passages can be a really daunting task, especially since one never knows whether there simply is no secret door, or the party is not yet skilled enough to find it. For nearly any secret, it is possible to find an NPC from whom the necessary information can somehow be extracted, but given the size of the dungeon and amount of NPCs, that doesn’t offer much consolation.

The new swimming skill is rather on the superfluous side – there are about a dozen ponds in the game, where a good swimmer can dive to the bottom to find essential items for the quest, among other things. Overestimating a hero’s abilities, however, results in death. The characters can be trained in swimming by diving in shallower ponds, but that usually comes with side effects, as clean water is hard to come by in the dungeon. The right way to do is, though, is to find a rubber duck, which allows to dive as long as it takes to reach everything. Some of the spells have been rebalanced a bit, and there are even a few entirely new ones. The most interesting are the summoning spells, which call elementals to support the party in battle. Some of the most powerful magic formulas are immediately forgotten after a single use, and have to be learned again.

Another big update applies to the weapons. Each weapon now has a range value – while the regular swords and axes can only be used from the front row, a pike or a halberd makes it possible to attack from the back, and also puts the backup monster groups within reach for the front row. Bows and crossbows finally allow to attack anyone from anywhere, and there are even some magic staffs that provide mages with ranged attacks.

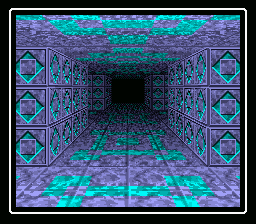

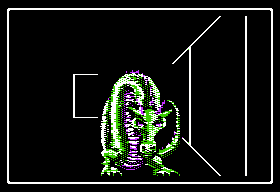

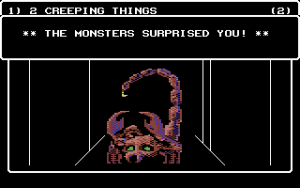

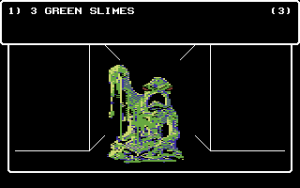

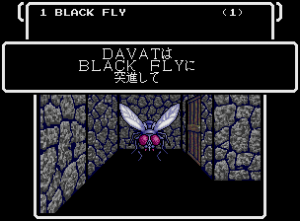

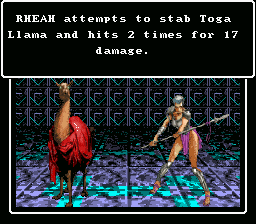

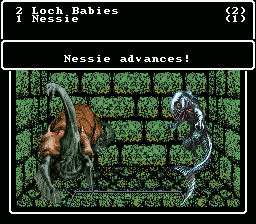

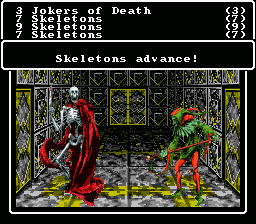

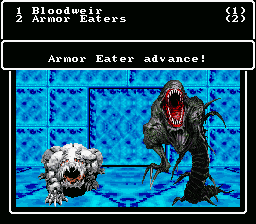

What D.W. Bradley didn’t touch was the engine for rendering the dungeons, so the graphics were hopelessly outdated when the game was released. According to Bradley, the game was actually completed well before Return of Werdna, but it was held back for an extended period of quality assurance to publish the games in order. The monster graphics are bigger and better than ever before, but all the computer versions still use the wireframe dungeons. Being a contemporary of Dungeon Master, which caused countless jaws to drop for its detailed dungeon graphics and lively monster animations at the time, Wizardry V‘s visuals were rather embarassing.

Just as The Return of Werdna, Heart of the Maelstrom is just brutally difficult. There are just so many things that can only be learned by trial & error, and given the unforgiving death mechanics of the series, a lot of times that means to restart from scratch. The final puzzle requires dozens of clues from all throughout the dungeon to consider, and the ultimate boss fight is cut from the same cloth. And that’s not even the greatest challenge: The adventurers can optionally visit hell (at dungeon level 777), whose demons make the main quest seem like an introductory chapter.

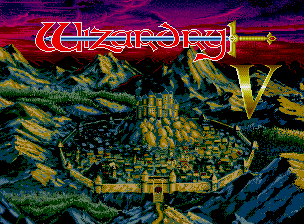

In the US, Wizardry V was still released for the Apple II, IBM PC and Commodore 64, but in Japan most of the old 8-bit platforms were ignored for this sequel. Only the PC-88 was still served, which is essentially the same as the PC-98 version, only in lower resolution. The enemy sprites were once again redrawn. The game was also released in CD-ROM format on the FM Towns, where it features a great redbook soundtrack and another set of entirely redrawn monster illustrations. These are extremely well detailed and veer a bit more towards a typical anime style, but at that grade they really clash with the naked lines of the dungeons.

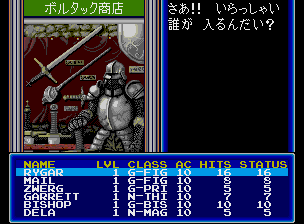

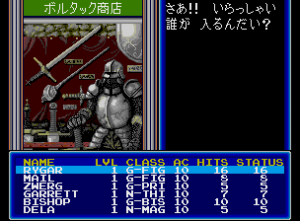

The PC Engine port for once makes thorough use of the CD-ROM medium. It not only contains CD audio, but also a voiced narration for the new intro and some of the NPC dialogs. The town has different graphics for each location, and some monster types that used to look identical have gotten individual sprites. The dungeon walls are very pleasing to the eye, although they’re the same for all levels, and the floors and ceilings are just deep black. Riddles where the solution had to be typed in on computers offer a small selection of multiple choice answers now, which of course makes them much easier. When talking with NPCs, the available keywords are also selected directly. This is the only version that offers torches and lamterns in Boltac’s Trading Post, an odd addition considering that light is on the lowest priest spell tier. Unfortunately, this port can not be played completely in English. The language for monster, item and spell names is selectable, but most of the menus and the conversations with NPCs are always in Japanese.

The SNES version is a bit of a disappointment compared to The Story of Llylgamyn, but after all it was released seven years earlier, on a measly 1 megabyte cartridge. There are not that many colors used, and the dungeon graphics tend to look a bit grainy, but at least there are different textures for each level. The town menus also lack the individual backgrounds for each store. Some of the comfortable features from the Lllylgamyn compilation are still missing, but the automap spell thankfully is there. Different to the PC Engine version, riddle solutions have to be put in manually, but NPC dialogs just run automatically, with the player character automatically asking follow-up questions. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be any way to ask some very important questions to some NPCs near the end of the game, so the final puzzle is almost unsolvable without outside help.

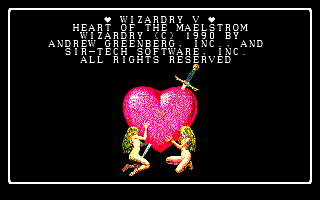

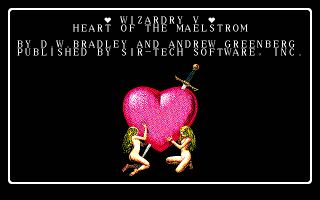

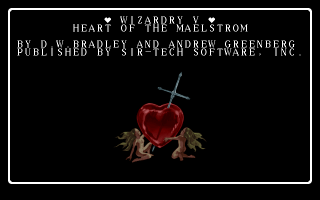

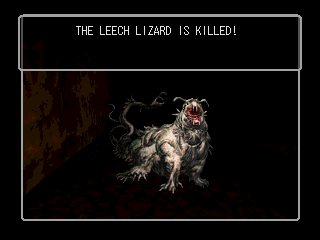

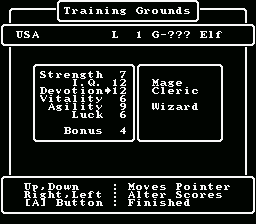

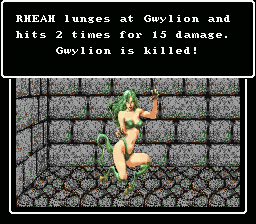

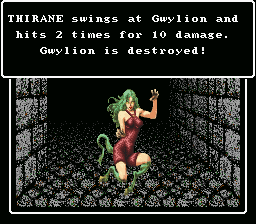

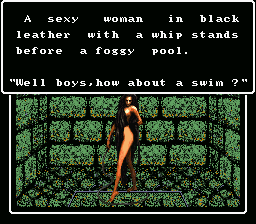

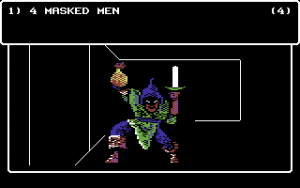

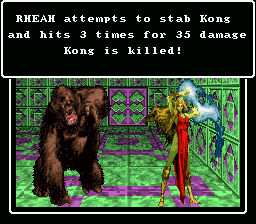

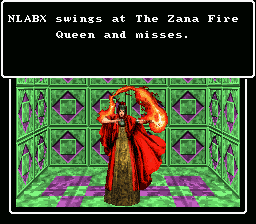

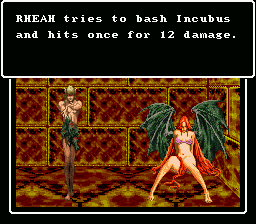

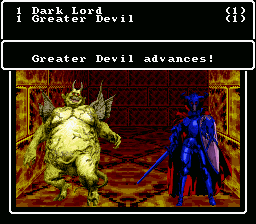

Since the Japanese versions still contained the English text, it was not much of a problem to bring this version back to North America, but it still took US publisher Capcom well over a year to get the job done. Typical for that era, there was a bit of censoring done to appease Nintendo of America’s family friendly standards. The formerly nude women holding the sword-pierced heart on the title screen are clothed in tunics, and some of the female enemies in the game were also given less revealing garbs. The Succubus was even entirely replaced by another sprite (a covered-up version of another female demon from the computers, which itself got a new sprite on the Super Famicom) and renamed to Vile Woman. Alcohol references also had to go, so in the US version there is a former alcoholic warlock who blocks the way and demands soda instead of rum. Nintendo’s stance against concrete religious references was also strictly enforced, so the priests where renamed to clerics, the bishops turned into wizards. There is also an enemy originally called “Unholy Terror”, which became “Awesome Terror” in the re-localization. Finally, the American release is afraid of speaking about death – enemies get “destroyed” instead of killed, and adventurers are “doomed”

The port contained on the New Age of Llylgamyn compilation for PlayStation is roughly based on the SNES version, although it suffers from terrible polygon graphics for the dungeons (wireframes are still an available option, though). The monsters are just cleaned-up versions of the 16-bit sprites, but they look a lot better for it. To provide players with an easy entry, there’s a level 5 party waiting to be recruited at the tavern.

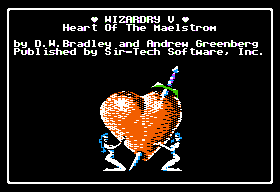

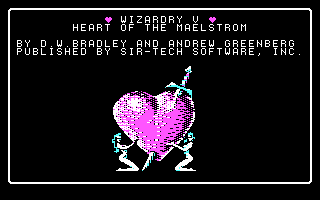

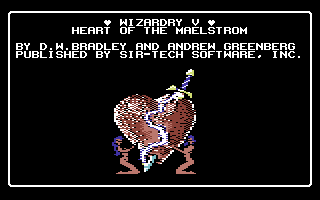

Comparison Screenshots: Title Screen

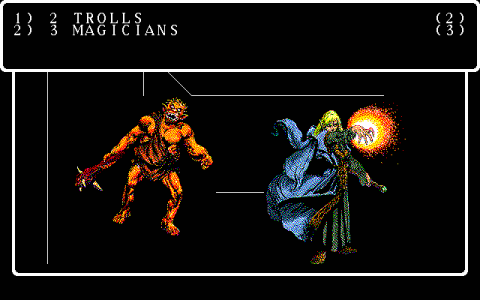

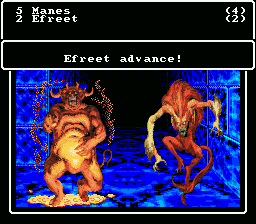

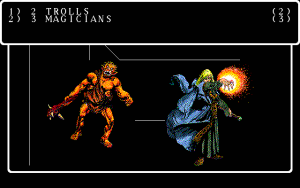

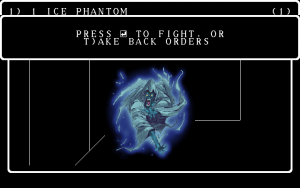

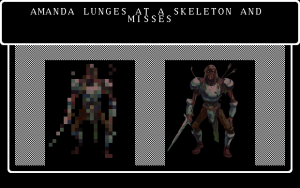

Comparison Screenshots: Monsters

Comparison Screenshots: SNES Censorship

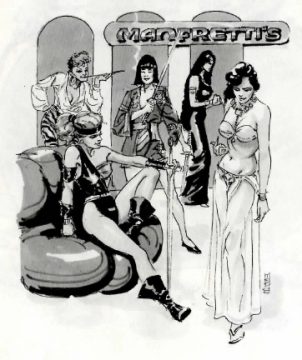

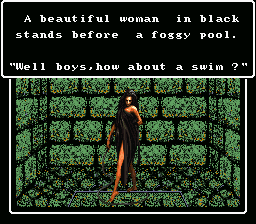

Comparison Screenshots: Sexualized Enemies

Gypsy

Gwylion

Amazon

Unholy Terror

Succubus

Fay

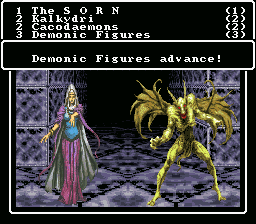

The Sorn

Royal Lady

Beauty