- Wizards & Warriors

- Ironsword: Wizards & Warriors II

- Wizards & Warriors X: Fortress of Fear

- Wizards & Warriors III

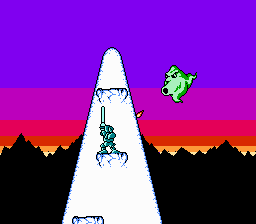

Kuros saw one more outing on the NES before the Wizards & Warriors series was laid to rest. The Game Boy iteration of W&W, released a couple of years earlier, had Rare carving W&W down to its core and making a standard platformer out of it. Zippo Games returned to take lead on the development of the final game, and they molded the W&W formula in the exact opposite direction, making an open-ended game that nowadays would get the “Metroidvania” label.

The story of Wizards & Warriors III: Kuros: Visions of Power, is that Malkil was not truly defeated at the end of Ironsword. The unusually elaborate opening of W&W III features an animated retelling of that previous battle with Kuros and shows that the evil wizard’s spirit got away, but not before zapping the good knight and knocking his helmet and sword away. Malkil flies off and takes up residence in a city called Piedup, where he imprisons its king and takes his appearance to fool the population. Kuros, in a daze, wanders the wilderness for a long time and eventually ends up at the gates of that same city. With his thoughts filled with revenge, he heads inside to make things right.

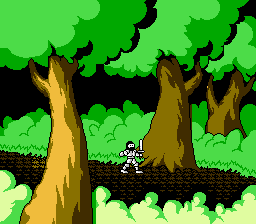

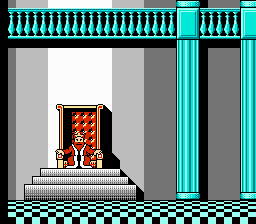

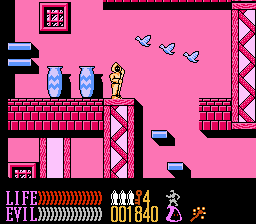

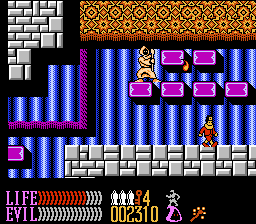

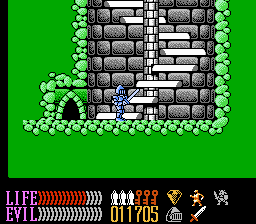

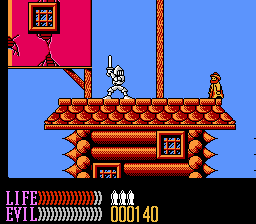

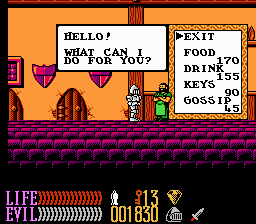

And it’s quite the initial shock if you are used to the previous games. There is no distinct level structure any more, and Kuros begins, not in a forest or on a mountain, but at the lowest levels of the city of Piedup. Villagers are walking around, minding their own business, and nary a monster is in sight. With no threats attacking you, your main goal in the beginning is to simply find money, buy keys, and explore every door you can access.

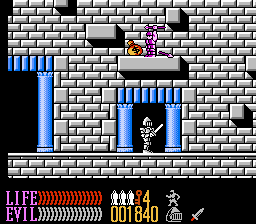

The city’s buildings are built on stilts, supposedly as a means of space conservation, and the royal castle sits high above the common folk so that the nobility can avoid the filth and disease of the peasants. In reality, though, this provides a sense of vertical progression in the game, as what would a Wizards & Warriors game be without a lot of senseless jumping and climbing? A lot less frustrating, for one thing. Admittedly, though, it never gets anywhere near as bad here as it did in Ironsword, where the multitude of slopes and charging enemies made getting around incredibly cumbersome.

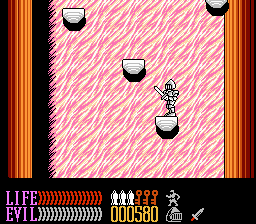

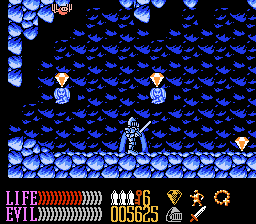

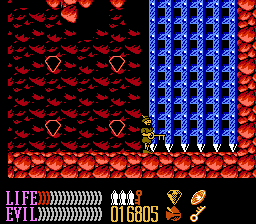

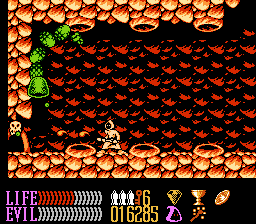

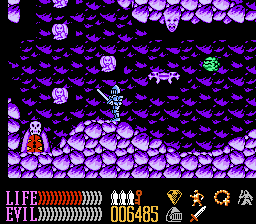

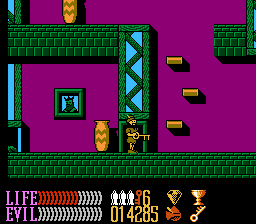

Ascending ever higher gets Kuros to different features of the castle, and delving beneath the city gets him to its old diamond mine, a series of caves called the Underworld that are now filled with monsters and other threats. There is no in-game map, but the game’s developers very smartly color-coded the areas. For instance, the highest section of the Underworld is colored red, the middle green, and the very bottom purple. While it’s still somewhat easy to get lost, you at least have some idea of where you are.

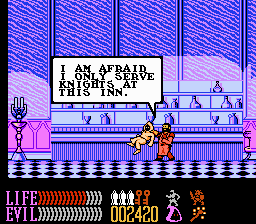

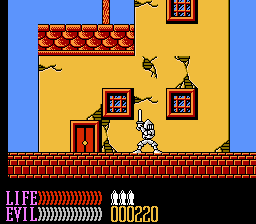

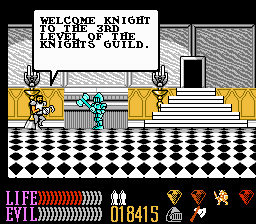

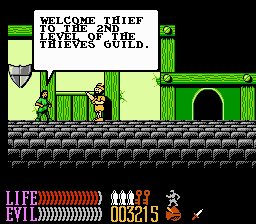

The main gimmick in W&W III is that there are three sets of disguises that Kuros can pick up from various guilds scattered about: knight, thief, and wizard. Many years later, the Trine series would use these same three character classes for its puzzle-based platforming, but here they form the basis for unlocking new areas in the large map of Piedup. Each guild has three locations scattered around the city, and they’ll teach Kuros a new ability for their respective class, such as using a crowbar as the thief to enter buildings via windows, or levitating into the sky as the wizard. Gaining one of these skills (nine altogether) then opens up one or more new areas of the map to explore.

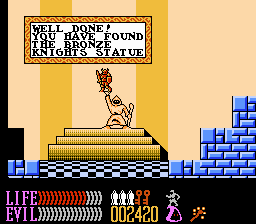

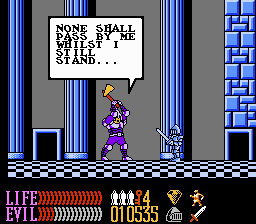

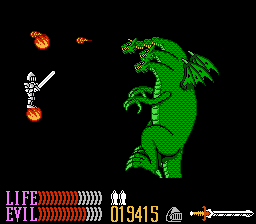

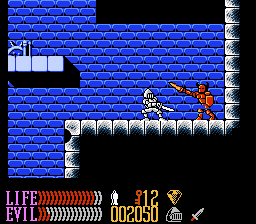

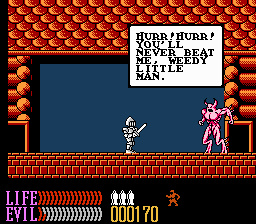

First, though, Kuros needs to do two things to get access to the guild. He has to track down the guild’s lost statue, usually found behind a locked door or boss elsewhere. Then, using his basic knight form, he is tasked with completing a test for the guild: a tedious platforming challenge, ending with an even more tedious boss fight. These fights are not overly difficult to beat, but they require studying the bosses’ attack patterns, dashing in when they momentarily pause to get in a sword strike, and then backing out of the way for a good while until they pause again. They have a lot of health, too, especially the level 3 guilds, so the battles are more a fight of attrition than anything else and take a long time.

Speaking of fighting, W&W III drastically alters the series’ sword fighting mechanics. In all the previous games, you press the B button to swing your sword. Holding down a directional button as you do this results in a high or low swing, but you mash the B button to swing your sword over and over again. This is no different than the vast majority of NES games. The B button launches Mario’s fireballs; it swings Link’s sword and Simon Belmont’s whip.

W&W III completely reverses this, and it never feels intuitive. Holding down B simply readies your sword in an upward direction. You then have to press the D-pad to swing your sword in the direction you press. Want to swing diagonally towards the enemy’s head? Hold B and then Press UP + RIGHT over and over again. Need to duck and jab towards the enemy’s feet? Hold B and then press DOWN + RIGHT again, and again, and again. This same control scheme applies to Kuros dressed as a thief using a dagger, and as a wizard throwing fireballs. The developers so badly wanted an extra directional input on the controller and would have loved the dual-stick setup now standard on consoles. While what they did does arguably work, it never feels comfortable.

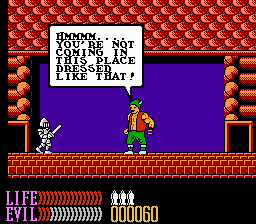

Playtesting most likely found that everyone stumbled with the revamped combat, so the developers had two choices: #1) rip it out of their codebase and start over again, or #2) simply place a note in the instruction manual under the “Special Warnings” section that you should practice Kuros’ new style of sword fighting as much as possible before you actually engage in combat. (They went with the latter.) Thankfully, there is far less fighting in W&W III than in any other W&W game. The screens aren’t inundated with enemies as in the past NES entries in the series, and other than the boss fights and a couple other minor enemies that serve as gatekeepers, you can largely make your way around the city without fighting anything at all.

In fact, a unique feature of the game is that each disguise allows safe passage in certain parts of the city. The knight is left alone by the inhabitants of the castle areas. The thief can walk around without incident in the lower rundown areas of the city, while the wizard is mostly left to his own devices in the Underworld. Use a different outfit in those areas, and the natives will start attacking you. For all intents and purposes, however, you’ll use the thief most of the time for his speed and ability to get around and into locked doors and windows.

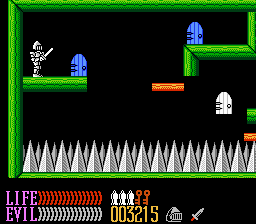

W&W games are known for their difficulty; the original one is incredibly easy, while the second one is near impossible to beat. W&W III’s difficulty fits somewhere in between. The two main challenges are getting lost and the guild challenges. Writing down notes as you go is practically a requirement if you don’t want to wander around aimlessly later on while trying to remember where that one guild you stumbled across earlier is, or the location of the barrier that you can now safely pass with a new ability.

As for the guild challenges, they are initially unfair in that they punish you until you memorize the safest path to the end. Fall off a tiny platform or get knocked into a pit by a flying arrow, and you lose a few bars of health and have to start the challenge again from the beginning. If you started with a full life bar, you can only fail 5 or 6 times before you’ve lost one of your precious lives. There are no continues here or the password system from Ironsword, so you’ll likely have to start the game from the very beginning multiple times while you learn these challenges. But once you do, the game is largely a breeze.

There’s one more game mechanic that is very unusual, not just when compared to the rest of the W&W series, but to video games as a whole. W&W III treats your point count as your money as well. Defeating enemies doesn’t give you points this time around, but everything else you can pick up from the ground does. This leads to oddities such as getting paid for eating a food pickup, which nets you 10 points/coins. The shops from Ironsword return here, though expanded upon – they each have their own guild alignment. Towards the end, you’ll likely have tens of thousands of points, which you can spend to buy food whenever your health gets low, further lowering the overall challenge. Until then, though, most of your money goes towards buying dozens of keys to open the plethora of locked doors scattered around Piedup.

From a presentation standpoint, the graphics are definitely the nicest in the series and rank among the better NES games. They’re colorful and nicely detailed (compare the subtle cracked facades in the lower, poorer city areas versus the ornately-decorated knight guilds), and really help give a sense of time and place to the world. The boss designs are a step down from Ironsword, though, where they were screen-filling terrors; here, they’re mostly reduced in size but much more mobile and chase Kuros around.

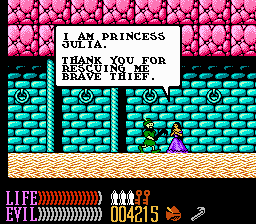

The music, again done by Rare’s in-house composer David Wise, is catchy and memorable. In a nice touch, Kuros’ various disguises have their own music that plays as you wear them. Unfortunately, most of W&W III’s soundtrack is only used in very specific locations, be it a guild (each class has its own theme), a guild store (again, each has its own theme), or the three rooms containing an imprisoned princess. The game does have a fairly extensive soundtrack, but for the vast majority of the time, you’ll be listening to the songs that accompany Kuros’ handful of costumes. And if you do in fact wear the thief outfit most of the time to get around quickly, its song will very quickly turn into an earworm and never leave your head.

W&W III was initially released in North America in 1992 after the SNES had hit shelves the year before, so it was mostly overlooked. It’s a shame the series died and never made the move to a 16-bit system, as this final game showed a promising new direction for it and could really have taken off with the extra processing power and storage of the newer consoles. It also arguably finally found the right balance of difficulty to keep players engaged but not overly frustrated.

It should also be noted that W&W II and III bookended Zippo Games’ NES development. Their first attempt at console development was Ironsword, contracted to them by Rare. They did a couple more projects for Rare after that, most notably Solar Jetman, before developing W&W III. Sadly, according to an interview many years later with Ste Pickford, one of the two brothers who founded the company, they were struggling towards the end of its development. The Pickfords sold the studio to Rare, and they became Rare Manchester. As is often the case with buyouts, employee morale suffered, and just about everyone left the company before the game was 100% complete. The studio was shut down, and one of the developers finished the game on their own and turned it over to Rare.

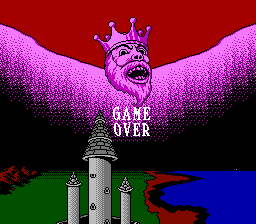

The ending to Wizards & Warriors III: Kuros: Visions of Power suggests that there were plans for another sequel at some point. When Acclaim, the games’ publisher, went bankrupt in 2004, the rights to the series and many other Acclaim properties went to Throwback Entertainment, who are mostly known for restoring older, lesser known games to Steam via emulation. There are, as of yet, no hints that they plan to bring back Kuros and Malkil for another battle of might and magic.