Xanadu is one of the most important Japanese RPGs developed. According to Falcom’s website, it sold more than 400,000 copies and is one of the most successful PC games in the country. It’s the second title in Falcom’s Dragon Slayer line, which aren’t technically related, but the early titles shared much of the same staff, and you can find small similarities and recurring elements between them.

Xanadu was the summer capital of Kublai Khan, ruler of the Mongol Empire. Its name has become synonymous with “wealth paradise”. Many unfortunate people have surmised that these games had something to do with the much maligned ’80s Olivia Newton John movie by the same name – as one might guess, this is not the case. It’s a pretty standard RPG, with the basic goal being to crawl through dungeons, defeat enemies, find hidden crowns, uncover the lost Dragon Slayer sword, and kill the dragon Galsis.

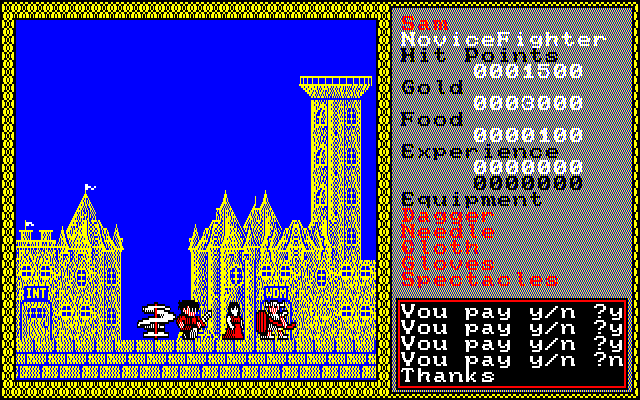

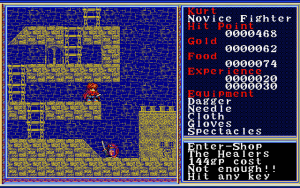

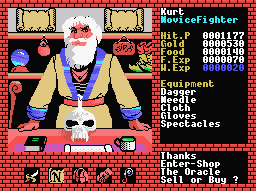

The game is a side-scrolling, dungeon crawling RPG. You begin in a town with no money and no strength. It’s filled with people, though they’re only there for flavor, and you can’t interact with any of them. A quick visit to the king will allow you to name your character and net you some cash, which you can use to train the hero in several different fields. Then you delve into the caverns below the castle.

Just getting into the dungeon is an abstract, nonsensical puzzle – unless you figure it out, you’ll wander around in a circle forever. (Fall straight down, head left until the hole you fell from scrolls off the screen, then head right. A shop will appear out of nowhere, in where case you can head back left and down the ladder to the first cave.)

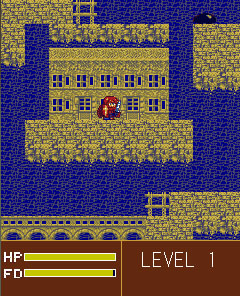

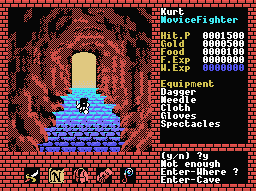

The look of the game should be familiar to fans of the NES game Legacy of the Wizard, which is actually the fourth game in the Dragon Slayer series. Each dungeon is several screens tall and several screens wide, though it loops horizontally. The goal is to not only find the exit, but gain enough strength and find enough equipment that will allow you to defeat the boss, before moving onto the next dungeon. There are ten dungeons in total. The game auto saves at certain points, but you can also save your game at any time at the cost of some gold. Navigation is incredibly confusing, considering there’s almost no real logic to the placement of platforms. You can climb up and down ladders, but can only “jump” a single square. Finding hidden rooms plays a big part in progressing too. This being an old computer game, the characters move a single tile at a time, so the movement feels very choppy.

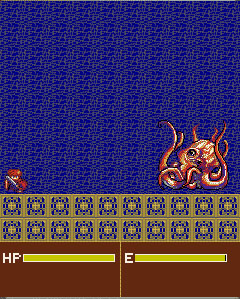

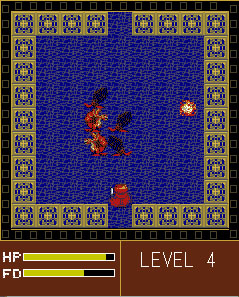

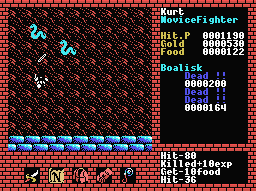

The landscape is, of course, littered with enemies. Colliding with one will bring up a separate overhead battle sequence screen where you engage in combat against multiple bad guys. Similar to its predecessor Dragon Slayer, you can attack them simply by nudging up against them. If you’re facing them and you’re more powerful, you’ll inflict a bit of damage, but if you’re attacked from any other side or are too weak, then you’ll take damage instead. You also have magic spells which allow you to attack from a distance. It’s also possible to run away from enemies by walking off the side of the screen. If you have an elixir, you can revive from the spot you died, but otherwise you’ll lose your money and be tossed back to the save point.

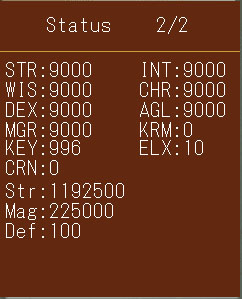

You also need to keep track of your Karma stat. Every enemy in the game is classified as either “good” or “bad”, even though they all will attack you. If you kill too many “good” enemies, your Karma will raise. There are a few other things that will increase too, like saving the game when you don’t have any money. In order to lower your Karma, you need to drink poisonous black potions, which deplete a good chunk of your HP. These potions cannot be purchased and must be found during exploration. None of this really makes any logical sense, of course, but so it goes. Keeping your Karma low is important for many reasons, as you can’t enter the final dungeon or get the Dragon Slayer sword unless it’s kept under control.

Leveling up your character is a very important aspect of the game. Melee and magic experience is distributed separately, so you need to attack with both methods if you want a well rounded character, or just stick to one if you want to concentrate in that area. To level up, it’s necessary to go to a temple after reaching the required amount of XP, but they won’t let you in if your Karma stat is too high.

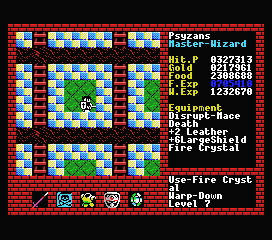

Beyond experience points, killing enemies will also grant gold, which you can use to buy equipment from any of the shops strewn throughout the caves. You also need to replenish your constantly dwindling food supply, lest you want to starve to death. Some areas are locked off and require keys to proceed.

Your weapons also level up independently, so you need to continue to reuse them before they gain in power. As a result, you might feel a little weaker when you get new equipment before you fully break them in. The number of enemies is limited in each dungeon, so it’s important to carefully manage your resources and experience distribution.

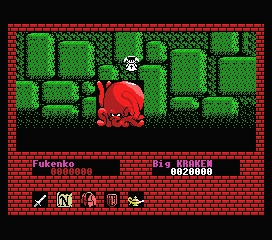

There are also numerous castles and towers underground. Upon entering the perspective changes to an overhead perspective like the battle scenes; these effectively act as dungeons. They are dark at first, but can be lighted with lamps from chests dropped by defeated enemies. Further items that help during the quest include spectacles to read an enemy’s status, invincibility rings, healing potions and a mantle that allows you to pass through walls for a short time. At the end of some mazes, a giant boss creature guards the main treasure. Only these bosses are fought in the side-view perspective, which makes it very difficult to reach them because of their long moving tentacles. However, the size of these sprites was considered extremely impressive at the time.

Xanadu is one of those games that’s clearly very advanced for the mid-1980s, as it’s a huge game with lots to see and kill. The game is quite difficult, as it’s essentially a series of puzzles you need to figure out over several playthroughs, learning where all of the hidden stuff is and figuring out the best way to allocate resources. Gamers who were able to complete the game could copy their clear data onto a floppy disc and send it to Falcom to get a certificate of completion, a true badge of honor. But its difficulty is also one of the reasons why the game became so popular. It was released around the time that the computer magazine industry was beginning to flourish, and of course, many of them featured strategy guides on how to beat this complex game. This ended up basically being free advertising, which led even more people to purchase it to see what the fuss was about. Of course, from a modern perspective, it’s even more difficult to play. Without any guidance, the mechanics are fairly obtuse, and it feels like endless grinding and stumbling about, especially with the repetitive visuals.

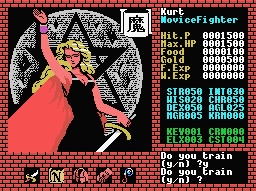

The original releases of Xanadu were for the Sharp X1, Fujitsu FM-7, NEC PC-88, PC-80, and PC-98 home computers. The X1 version, which was the first one released, was published on tape as well as disk, though the load times for the tape version are insane. The PC80/88/98 versions are all similar, with slightly better visuals than the X1 version. The FM-7 version adds support for PSG and FM music. The controls are a little bit dicey in this version, since you’ll automatically continue to move whenever you hit a direction, and need to hit it again to stop.

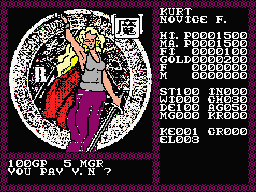

The game was ported to both the MSX (on cartridge) and MSX2 (on disk). The graphics are lower resolution, but in general it actually looks a bit better. Curiously, the MSX cartridge version is actually an improvement over the MSX2 version – it looks nicer, for starters, as the MSX2 version sticks to a color palette similar to the PC-88 version, plus the cart version adds unique backgrounds for the bosses. The cartridge also has an entirely different (and expanded) soundtrack that was written by Mieko Ishikawa and Yuzo Koshiro which utilizes PSG synth, rather than the FM music of the PC-88 game. In most versions, you’re given money from the king, which is used to allocate points in certain fields. The MSX version just gives you points directly (and less money), because in this version only, you can return to the town to further improve your stats. Items can only be bought at a hidden shop in the first training ground area. Items are cheap, except in the MSX version, where they are prohibitively expensive. The load times are also eliminated, plus it includes the ability to save your game.

The Japanese home computers also received a second release titled Xanadu Scenario II: Resurrection of the Dragon. This was released for every platform of the original game, except for the MSX platforms. It’s technically an expansion set, since it requires that you have the original Xanadu disks in order to create your character, and it uses many of the same basic graphics. But it adds a significant amount of new features that it almost feels like a sequel. Beyond including new and different enemies, the game is now non-linear, and you can explore any of the eleven dungeons in any order. However, some are more difficult than most, so it’s generally to your advantage to stick to the lower level dungeons at first. The dungeons are 8 screens wide by 8 screens tall, compared to the 16 wide by 4 tall layouts of the original game. You can also sell back items, and each shop buys and sells different items at different prices. There are also slippery floors, and the concept of weight, effectively limiting the amount of items you can carry. Overall, it’s actually even more difficult than the original version.

The soundtrack is also greatly expanded, with each dungeon having its own song. Most of the music in the original game consisted of a single song, “La Valse Pour Xanadu”, with a basic melody that was played at different tempos depending on the scene. The soundtrack in Scenario II is completely new, with many more tracks. The music was composed by Takahito Abe and Yuzo Koshiro. This was actually the first work by Koshiro. He did not write tracks specifically for Xanadu, but rather he submitted a demo of his music to Falcom, who ended up purchasing the rights and using his work in the game.

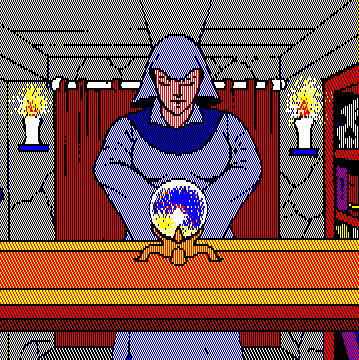

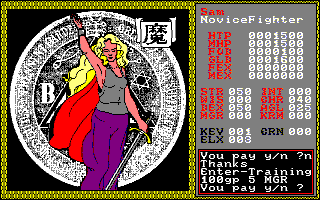

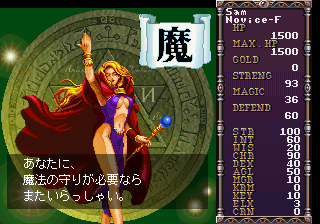

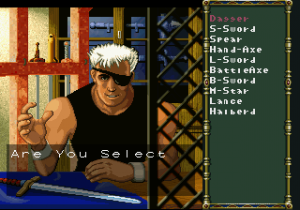

In 1995, Falcom released Revival Xanadu for the PC-98. The graphics are improved, but only slightly, with the visuals improving from the 8 colors of the PC-88 version to 16 colors, as well as FM synth music. The shopkeeper portraits and character sprites are more detailed, but the backgrounds are still the spartan blues as before, and the scrolling is still pretty choppy. Compared to the other version, melee combat is much more difficult, almost requiring you to play a wizard. It was also followed up by a Revival Xanadu 2 Remix, which is technically analogous to Xanadu Scenario II, though it’s been drastically reworked with different levels and enemies. This version also includes Revival Xanadu Easy Version, which is, as the title suggests, an easier version of the first release.

The first Revival Xanadu was ported to Windows 95 by Unbalance, who also developed versions of Romancia and Asteka II for the platform. Visually it’s similar to the PC-98 version, but is stuck using WAV recordings of the music rather than native FM synthesis (which probably would not have been able to replicate it satisfactorily), and it’s extremely glitchy, with a number of small inaccuracies from the original versions. It doesn’t play nice with modern operating systems either. As a result, the digital distribution platform EGG just features emulations of the PC-98 versions. A mobile port was based on this version.

Xanadu is also one of the three games on the Falcom Classics disc for the Saturn, released in 1996 and developed by Victory-JVC. Despite its name, it’s actually based on Revival Xanadu. The graphics are much better, but still pretty subpar, and the music arrangements are terrible, considering the capabilities of the system. Although the scrolling is smoother than the PC versions, the ridiculously awkward jumping is still present. There is a “Saturn” mode that streamlines some of the processes a bit and makes it a little less irritating (it eliminates the puzzle to get into the dungeons, for example, and makes it easier to create the character), but it’s not nearly enough to make it playable for modern audiences, even back in the mid-90s.

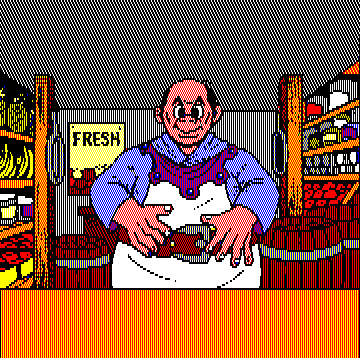

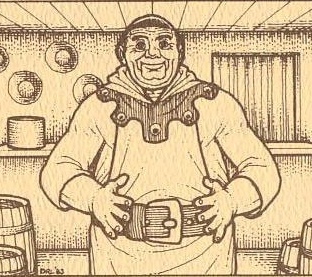

Amusingly, a lot of the shopkeeper graphics in the original releases were traced from the manual for Ultima III, which caused an especially awkward moment when Falcom demoed the game to Origin in search of American publishers. (The complete comparisons can be seen in our Tracing the Influence feature.) Subsequent ports changed them completely. Ultimately the game never found a publisher outside of Japan, though for non-Japanese speakers it doesn’t really matter, since most of the text in the game is in English anyway.

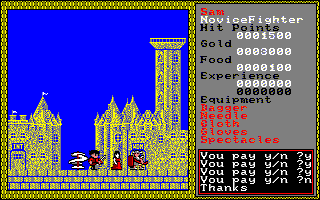

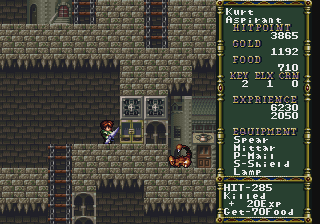

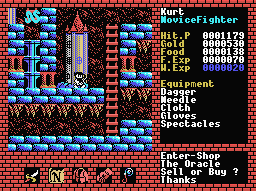

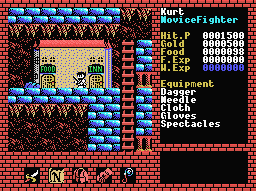

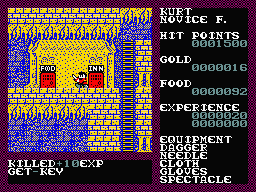

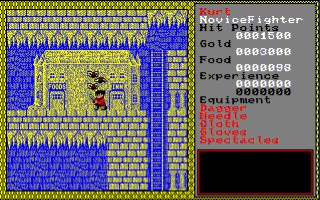

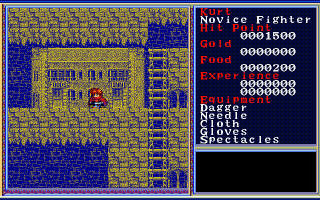

Screenshot Comparisons