Stand tall and shake the heavens!

Released in 1998, Square’s underrated RPG Xenogears is the product of two mostly unrelated trends. The first one is that strange period in Japanese geek culture when everything became surreal, post-modern and filled with unreliable narrators, psychological themes and religious references – the same one which gave us anime like Ghost in the Shell, Neon Genesis Evangelion or Serial Experiments Lain and video games like Radiant Silvergun or (to a certain extent) Final Fantasy VII. The second one was the game designers’ tendency to create massive multi-part projects to be developed over the period of many years that almost never really came to fruition as they often went over budget and almost never sold well enough to make up for it – the one that a few years later resulted in the forever unfinished Shenmue series.

Just like with Shenmue, the story of Xenogears was supposed to be spread over many chapters, although some of them were not supposed to be games (the developers wanted to experiment with other media such as books and anime). In contrast with the former title’s more personal narrative, Xenogears series was supposed to be a multi-generational epic spanning a few planets and tens of thousands of years. Unfortunately, only a single game was created, and even that didn’t exactly come out the way it was supposed to be as the game’s second disk had to be reduced to mostly the characters telling you what happened as opposed to a traditional JRPG gameplay of the first one (there’s an unconfirmed rumor that the original plans were for Xenogears to be shipped on 4 CDs and given how much story has been hastily crammed into a second one it doesn’t sound impossible).

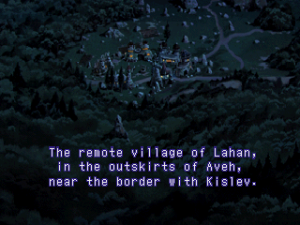

The plot of Xenogears is focused mostly on the character of Fei, an amnesiac painter living in the Lahan village on the border between warring nations of Aveh and Kislev. As per genre tradition, Lahan doesn’t last very long and our hero will be thrown into a conflict much larger than he imagined as he’ll be forced to pilot Weltall – a powerful Gear (basically a giant robot made by an ancient civilization) stolen by one military from the other. Along the way, he’ll meet a colorful cast of characters (including a higher than average number of mysterious villains wanting to use him for their incredbily complex schemes), discover many secrets and fight in battles of rapidly increasing importance – from personal survival to national conflicts to the affairs of gods.

Characters

Fei Fong Wong

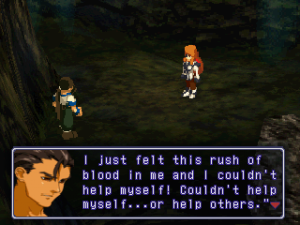

An amnesiac painter living in Lahan after a mysterious masked man brought him there when he was wounded and unconscious. He’s a reluctant hero who at first has a hard time accepting his (much more important than it seems) role in the universe. He’s a martial artist and pilots a Gear called Weltall (German for ‘universe’). Fei’s character arc deals with him recovering his repressed memories and accepting the consequences of his actions. His name is a reference to a Chinese folk hero Wong Fei Hung.

Elhaym ‘Elly’ van Houten

A talented Gear pilot from Gebler, an advanced military force which aids the nation of Aveh. She struggles between her relationship with Fei and the loyalty to her superiors while slowly learning to doubt the ideology she learned in her home country – namely that she is one of the ‘Shepherds’ and as such has a right to decide the fates of ‘Sheep’. Her weapon of choice is a rod and her Gear is called Vierge (French for ‘virgin’).

Citan Uzuki

A doctor and a scientist living in the mountains near Lahan. He apparently knows much more about the world around him than most of the characters but for several reasons keeps most of it secret. He’s probably the most overpowered character in the game – that also extends to his role in the story as he often rescues everyone else from trouble. Citan is a martial artist and a swordsman (although he gets his first weapon relatively late in the game) and pilots a Gear called Heimdall (named after a god from Germanic mythology).

Bartholomew ‘Bart’ Fatima

A hot-headed leader of the group of ‘sand pirates’ stealing Gears from Aveh military with a help of a strange submarine called Yggdrasil (named after a world tree from Germanic mythology) that is able to travel through the desert. He’s actually a rightful heir to the throne of Aveh and is preparing to take back his country from the usurper known as Shakhan. Bart fights with a whip and pilots Brigandier.

Kahran ‘Kahr’ Ramsus

A Gebler commander serving as a major villain for a large part of the game. He’s an intelligent and ambitious leader who introduced meritocratic reforms to his millitary but can also be quite ruthless and single-minded. Kahran considers Fei to be his archenemy and is so obsessed with the idea of defeating him that he seems to put Gebler’s plans in jeopardy. He pilots a Gear called Wyvern.

From the beginning to the end it’s obvious that the creators of Xenogears where heavily inspired by Neon Genesis Evangelion. Some of the similarities between the two include the use of christian and gnostic themes, references to German philosophers (although while Evangelion borrowed some of its ideas from Schopenhauer, Xenogears seems to prefer Nietzsche), focus on the psychology of major characters, a reluctant protagonist (with obligatory refusal to pilot his robot), prominent theme of parent-child relationships, giant robots and conspiracies involving shadowy organizations. Some of the visual elements are also borrowed from that show as well, especially in the beginning and the end with the anime-style cutscenes (made by Production I.G., a studio which had a part in the creation of End of Evangelion movie) utilizing quick montages that include looped footage, close-ups of characters’ faces and eyes, computer displays and typography.

This is not to say that Xenogears is just a rip-off of a popular TV series. It’s a SquareSoft game from the late 1990s after all and it wouldn’t be complete without some of the company’s signature narrative elements. As can be expected from Square, there are evil empires, rightful leaders trying to regain power, a destroyed hometown, a forgotten civilization and not one but two lands in the sky. Unfortunately there’s also some silliness that can break suspension of disbelief like a mascot-like creature growing to gigantic size and defeating a Gear or two characters finding out they’re long lost brothers. But the less said about that the better.

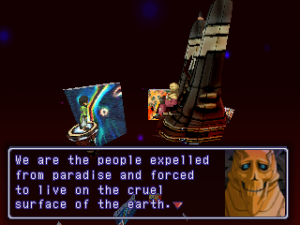

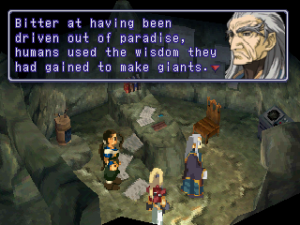

The use of religious symbolism in the game is surprisingly well thought out, far from randomly namedropping unrelated christian concepts that was so commonplace in 1990s Japanese media (no matter how you look at it, the crucifix-shaped explosions from Evangelion didn’t really make sense). Everything is somehow related to its original meaning, although usually recontextualized in interesting ways: in this world the Babel Tower and its builders who rebelled against god are connected to one of the flying cities you’ll be visiting near the end of the first disk while the giants (Nephilim) are heavily implied to be the same as exceptionally powerful Omnigears. While most things in Xenogears are eventually explained with some in-universe science, it makes sense that they’ve gradually turned into myths and legends given all the destructive wars and the complete control Ethos (one of the two Church-like organizations in the game) had over the historical documents. The reimagining of the Gnostic duality between a good spiritual God and an evil materialistic Demiurge is a thing of beauty, with the mystical Wave Existence trapped inside a powerful, godlike machine Deus.

The other duality of Xenogears is a sort of male-female dichotomy exemplified by the statue of two angels in the city of Nisan, the existence of all-male and all-female Churches (Ethos and Nisan sect), various past incarnations of Fei and Elly, Emperor Cain and Queen Zephyr ruling two flying cities and, most explicitly, Anima and Animus. The latter is the reference to male and female ideals in the theories of Carl Gustav Jung and it’s not the only time Xenogears uses concepts borrowed from classical psychoanalysis – another major theme in the game is the freudian structure of personality with ego, superego and id.

There’s also a philosophical aspect of the Xenogears story that’s mostly based on the works of various existentialists – the characters are often seen searching for their purpose, more often than not in direct opposition to the wishes of political and religious powers. There are many references to Nietzsche, often recontextualized the same way the game deals with religious themes: the recurrence of events (although here it’s connected to the cycle of reincarnation as opposed to the recurrence of universe as a whole), Grahf’s search for power and desire to kill god, a scientist trying to become more than a man. All in all, Xenogears is quite erudite and people with an interest in some of its themes may want to find out about the things it references as it allows to see some of the game’s events in a different light.

Carl Gustav Jung (left), Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (right)

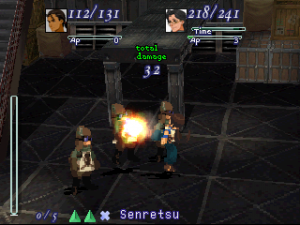

Gameplay-wise, Xenogears offers an interesting variation on the console RPG genre. The game has two battle systems: one for fighting on foot and one for Gear fights. Fighting on foot is similar to the way it’s done in other Square games: there’s a level system with characters progressing in a pre-programmed way, with the player modifying them by changing their equipment which consists of a weapon (although many characters don’t use one) and three accessories (keep in mind that armors and helmets are also classified as accessories). The combat is turn-based, with an active time battle system similar to the on in Final Fantasy games. A major difference is the attacking as the player must use triangle, square and cross buttons to input attacks of varying strength (triangle is the weakest, cross is the strongest). Those attacks take different amounts of ‘action points’ and how many of those does the player have depends on his current level. By using different attacks the characters will gradually learn ‘deathblows’ – powerful attacks with their own dedicated animations. They’re far stronger than other combinations but relying too much on them will impede learning new ones, leaving the player unprepared for the more difficult enemies.

Gear battles are quite similar to on-foot battles but there are a few notable differences. First of all, Gears require fuel to operate and there’s no reliable way of refueling in the dungeons or during combat (it’s possible to regain some by using ‘charge’ option during fighting but it’s only good for emergency situations as the amount gained that way is rather small). There’s also no reliable way of repairing damage to the Gear outside of Gear shops – there are equippable ‘fix frames’ somewhere around the halfway point but they’re also an emergency measure because of high amounts of fuel they take. For this reason, Gear-based segments are somewhat of an endurance test where being well-prepared and well-equipped (that can’t be stressed enough: Gears don’t gain levels and their stats are dependent on three pieces of equipment: engine, frame and armor; those are expensive but important so if you have to choose between upgrading a Gear and buying more healing items, always go with better parts for your machine) is the key to your success.

Gears also don’t have action points and can only attack once per turn (deathblows described later are an exception). This increases their attack level which allows them to use deathblows, although their specifics are different from the deathblows learned by the characters. Gear deathblows consist of two attacks, the first of which determines what attack level is required to perform it (1 for triangle, 2 for square, 3 for cross) and executing them lowers attack level by deathblow level. If a Gear stays in the third attack level for a while, there’s a chance that it will enter hyper mode (represented by an infinity symbol) where it has access to extremely powerful attacks and can regain much more fuel by charging. It’s a pretty fun feature but only practical during boss fights.

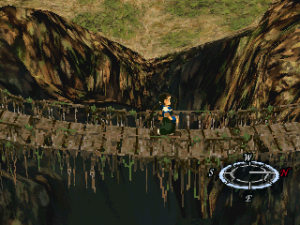

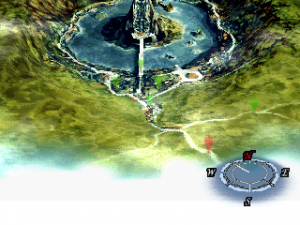

Of course, Xenogears is not only about combat. There’s a lot to explore in this game and the level of detail put into the locations is amazing. There are many places that are technically useless, only providing flavor to the game’s world: cities have residential buildings, bars and hotels, indoor locations have bedrooms and kitchens, royal palaces have great chambers for the aristocrats and smaller rooms for the servants etc. The dungeon design isn’t as good though as there’s a huge amount of backtracking and, worst of all, platforming. And while Xenogears is a great RPG, it’s one of the worst 3D platformers ever with unhelpful camera angles, small margin of error, vertical design (so that when you miss one jump you might need to start over) and most of mistakes being punished with annoying random encounters. The nature of Gear-based levels also means that those encounters can easily exhaust your resources so a lot of frustration will be had in the mountains on Aveh-Kislev border and in the infamous Babel Tower (I might lose a bit of gamer cred for admitting that but I used emulator savestates during the latter).

The game also features two minigames. The first one is Battling: a sport competition in which the opponents fight in their Gears. It doesn’t use standard Gear fighting system, instead opting for a simple 3D fighting game. There are a few nuances there as different terrain types affect the performance of Gears and attacking from the distance may cause them to overheat but it’s generally easy to grasp and fun for a little while. The second minigame is an implementation of a card game speed. It’s nothing really special and plays just like a card game, although the idea of representing it by character running on the giant cards is quite funny.

From the graphical standpoint, Xenogears looks very good. The art direction is impressive – epsecially the look of some of the locations, which the developers showcased by zooming and rotating the camera around them when you visit them for the first time. The look of each place is always related to the story and geography behind it – towns in Aveh have a distinct Middle-Eastern look, the capital of Kislev is industrialized and polluted, Nisan looks rural and idyllic etc. The locations are fully three-dimensional, although there’s sometimes a bitmap of a landscape in the background.

The Gears and larger enemies are polygonal as well, although they don’t look as good – it’s not a big problem for all the machines but large monsters really show the limitations of the old PlayStation hardware. People and human-sized (or smaller) creatures are sprite-based. The sprites are beautiful and detailed, with some really fluid animation (some of the deathblows are a real pleasure to watch, especially when the game decides to show them from a dramatic camera angle) and blend well with the backgrounds, although there is one problem with them: they’re a bit too low-res and get pixellated when viewed up close or from an angle. There are also quality issues with the anime cutscenes as they’ve been heavily compressed and the artifacts are clearly visible. Still, the game usually looks great and its visual style seems to be a natural evolution of the way SNES titles like Chrono Trigger looked like.

The soundtrack to Xenogears was composed by Yasunori Mitsuda of Chrono Trigger fame. Most of the tracks are orchestal type music, with a Celtic flair in places. Grahf’s theme sound especially tense and epic, with a pounding drum beat and an ominous melody. The battle themes are appropriately bombastic, and the Lahan theme recalls the “Millenial Fair” theme from Chrono Trigger, a jaunty little song that becomes much sadder once the town is completely destroyed. The overworld song is rather peaceful, with a vocal version appearing on the game’s soundtrack. This track is sung by Joanne Hogg, who also sings the ending song, “Small Two of Pieces”, as well as a few tracks in Xenosaga. The sound quality is impressive considering it’s all generated by the PS1 sound chip rather than being a recording of an orchestra. The sound effects are also mostly typical SquareSoft fare, with an exception of a few satisfying bits of voice acting (well, mostly shouting and grunting) used during the combat.

Xenogears doesn’t have too many bugs when played on the original hardware. There are a few clipping issues here and there and the pathfinding is pretty bad but it’s used so rarely that many players might not even notice it (the only times I can think of is when the player is chased by guards or soldiers). On emulators, PlayStation 2 and PSP there are some glitches with camera being stuck in weird places during the in-engine cutscenes, but more importantly there’s a certain attack used by one of the bosses which causes the game to hang up. There is no fix for this so the only thing the players can do is try to kill him quickly while hoping that he decides to hit them with something else.

The game’s biggest problem doesn’t lie with the technical issues though – the most annoying thing about Xenogears is its infamous second disk. As was mentioned before, everything changes from the typical RPG gameplay to brief descriptions of what happened. Those descriptions are also artificially padded by the painfully slow text speed. The narration is occasionally interrupted by a dungeon (which often contains a lot of backtracking and some obtuse puzzle) or a boss fight – and that’s pretty much the whole disk 2. The story during that part of the game suffers as well as instead witnessing the events you’re just being given a summary. Some of the planned subplots were also removed – there was an enemy who was supposed to switch sides and join your party and the end of disk 1; instead of that, the main characters simply convince him to leave them alone and he completely disappears from the story.

Xenogears is a controversial title. While some of the players will love its story and themes, many other will find playing through the annoying platforming sections and a disappointing disk 2 too frustrating for the game to be worth playing. The plot and writing will also have their detractors as it’s not unusual to consider such an amount of religious and philosophical references as a cheap way of making the game feel more intellectual than it is.

Xenogears really only comes recommended to more patient players with a bit of experience with PlayStation-era jRPGs. The game is extremely ambitious and the scope of its story is very large, but admiring them requires some knowledge of the genre and an ability to look past the game’s flaws. All in all, Xenogears is a JRPG masterpiece – but it’s quite an unpolished and unwelcoming one, with many rough edges and imperfections. In certain respects, the fans appreciate not what the game is but what it was supposed to be – after all, the finished product is just a small part of the original plans.

While the Xenogears project died with this game, Takahashi created two spiritual successors: Xenosaga trilogy and the more recent Xenoblade series. Unfortunately, due to the copyright reasons those titles couldn’t be set in the world of Xenogears and only contain small references to the original game. On the other hand, some of the plot elements in Xenosaga were originally supposed to be in the planned “chapter one” of Xenogears series, dealing with space exploration and the USS Eldridge ship from the introductory cutscene so it might still be of interest to those interested in Takahashi’s original vision. Xenoblade has no real ties outside of the title, however.

Links:

Xenogears guide at the old Gaming Intelligence Agency Website – an excellent resource on the game; includes a walkthrough and a detailed plot summart

Xenogears shrine on RPG Classics

Xenogears on Chaos2

Xenogears: Perfect Works fan translation – a Japan-only artbook which also explains some of the ideas that didn’t make it into the finished game

HD version of all Xenogears cutscenes (Japanese)