- XZR: Hakai no Gouzou

- Exile

- Exile: Wicked Phenomenon

Telenet’s XZR series is wild. It mixes religious historical figures and iconography, along with prolific drug-taking and a crazy storyline that sees you as a time-travelling Syrian Islamic assassin from 1124 AD. One who opposes the current Caliph, kills several real-world deities and eventually ends up taking out the leaders of present-day Russia and America. Yes, you read that correctly, you play a Shia Muslim who has to kill the president.

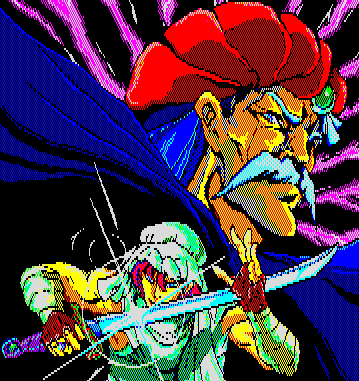

Originally released in 1988, the XZR series was developed by Nihon Telenet (or rather its divisions), the same company responsible for the Valis series, El Viento and a long list of other awesome Genesis titles. Telenet was also the owner of developers Wolfteam, which should require no introduction. Two of the US releases were then localized by Working Designs. So all in all, the series has a prestigious lineage, surrounded by some of the greatest games and people of the era. Despite their now mostly forgotten status, the games range in quality from fairly good to absolutely fantastic, blending action side-scrolling stages with RPG-lite overhead villages and anime cutscenes for excellent results. Perhaps they’re best compared with Popful Mail, Ys III or maybe even Zelda II – though if you weren’t a fan, don’t let that put you off.

As an aside, Telenet’s Exile series has nothing to do with the British series also called Exile, available on the BBC Micro, Amiga, Commodore 64 and other systems, also first released in 1988. For those interested, it plays very much like a Metroidvania in a sandbox world, free to explore, with its own living eco-system and realistic physics engine.

Below are the most prominent characters featured in XZR. The majority are based on real-world historical figures, and it seems that the developers grabbed a history book, opened it at the 12th Century, and then randomly grabbed anyone who looked interesting. The XZR plotlines are all insane, but wonderful because of that. Kojima, eat your heart out.

Main Characters

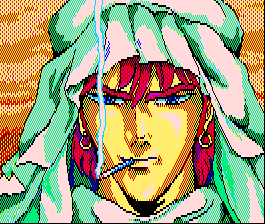

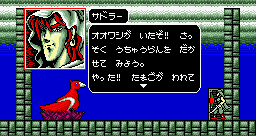

Sadler

Our protagonist, a Syrian assassin and secretly the son of the Caliph. When he was a baby he was kidnapped by assassins and raised as their own. In the first game he sets out to stop oppression and ends up killing his father, then the Russian general Secretary, and the President of the USA. In the second game a scouting mission has him embroiled in searching for the Holimax, to bring about world peace. In the end he realises world peace can never be achieved and so wanders out into the desert. The final game sees him focusing his sights on the nebulous concept of “hatred”. He also enjoys a good cigarette, except in the Japanese Megadrive and American Genesis games, where his cigarette is removed.

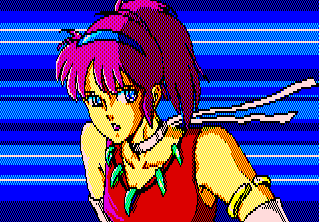

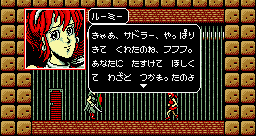

Rumi

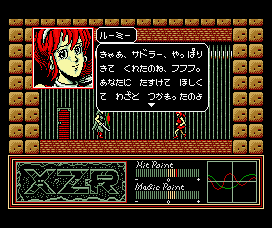

Supposedly Sadler’s love-interest and, according to the manual, an expert with knives and fluent in 8 languages. During the first game she’s only 16 years-old. Mainly she exists as the game’s anime eye-candy, repeatedly getting kidnapped in the first two games and then disappearing from the party to search for items like lost scrolls. Towards the end of XZR II she’s supposed to die in a cave-in along with Jofre but, thanks to wonderfully bizarre retconning, is written back into the third game. When playable she follows the fast-but-weak archetype.

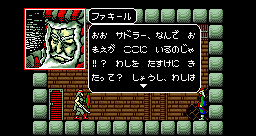

Fakhyle

A sorcerer who teaches Sadler magic spells. Generally though he’s lazy and prone to leaving the party to sleep at an inn or a shack. For some reason his face is visible in the computer versions, but console ports have his entire face covered. In the console version of XZR II he also needs to be manually recruited, whereas in the computer version is already in your party. When playable he has homing magic, but isn’t very powerful.

Kindhy

A strange giant of a man who never says anything intelligible, yet is apparently Sadler’s instructor. In the first game he’s gotten himself embroiled in the circus and needs to have his freedom bought back. After that he mostly follows Sadler around and doesn’t seem to do much. In the second game he’s equally as useless and by the time Wicked Phenomenon came round, he hadn’t changed much. Strong-but-slow when playable, but still useless.

Secondary Characters

Sufrawaldhi

A shrewd scientist whose analytical reasoning is not swayed by his emotions. As a result, he doesn’t hesitate to disobey Islamic law when he deems it necessary. When Sadler meets Sufrawaldhi later in the game, he tells Sadler that he faked his own death once he discovered his life was in danger. Hence needing to search his gravestone at the start of XZR. Since then, however, he has been covertly tracking Sadler to watch over him and keep him safe. Uses a gun as a weapon. Only found in the first two games on computer – he’s missing entirely from later console versions.

Caliph

Sadler’s father, who is assassinated by him in the first game, and seen in the opening cinema to the second game. Some speculate he is based on Al-Afdal Shahanshah, grand vizier of the Fatimid caliphs of Egypt, who was allegedly assassinated by the Batinis Hashshashin order in 1121 AD. He doesn’t play that great a role in either game.

Yuug D’Payne

Based on the real-life character of Hugues de Payens, Grand Master of the Knights Templar. Information on the real Hugues is scant, but the in-game Yuug plays the role of supposed-ally and then betrayer-turned-antagonist, and resides in Homis Shrine, which is actually the Temple of Solomon. He searches for the Holimax under the pretence of wanting world peace, but actually just wants to resurrect himself, for he is in fact the demon Shimbatha, possibly a reference to Samyaza in the Book of Enoch, a fallen angel of apocryphal Jewish and Christian tradition who is also quite possibly Satan.

Prince Larma

The Prince of India, his localised name is probably a corruption of Prince Rama, meaning he would be based on the legendary Prince Rama found in ancient Sanskrit epic Ramayana, by Hindu sage Valmiki. The title literally means “Rama’s Journey” and tells the story of Prince Rama (the seventh incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu), whose wife Sita is abducted by the demon king Ravana. Which kind of ties in with Exile’s Prince Larma’s fiance being kidnapped by a demon. Except that in Exile it’s a giant bird, not a 10-headed warrior.

Milieu D’Payne

Supposedly Yuug’s sister, she is engaged to Prince Lahma in India. She gets kidnapped by a giant bird called Garuda, which is based on the same-named mythic Hindu deity, said to be large enough to block out the sun. She ends up marrying Prince Larma, but how she could be the sister of Samyaza is never really explained. She doesn’t have much of an impact on the story other than to be rescue-fodder, and it’s doubtful she’s based on any real character.

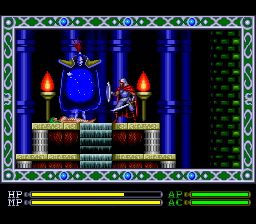

Mani

A giant, burning blue face in an Indian cave that reveals the truth of the world to Sadler. But first he has to be resurrected in a special ritual. Some online sources describe Mani as being the biblical Noah, but this is incorrect. He’s based on the historical figure of the same name. Born in 216 AD, Mani the prophet founded the major Iranian religion of Manichaeism. Around 240 AD he travelled to India as a missionary, apparently converting a local Buddhist king, and spending several years teaching in India. While history says he returned to Persia before dying, it does tie in with the Exile story.

Ninkan

A Japanese monk imprisoned on one of Japan’s Izu Islands. While there is speculation that he’s based on Buddhist monk Nichiren (1222-1282 AD), who also upset the authorities, Ninkan is in fact based upon a real Japanese monk of the same name (仁寛, which can also be read as Hitoshi Hiroshi). He was an obscure figure who founded the sexual cult known as “Tachikawa-ryu”, and taught that sexual union was a means for directly obtaining Buddha-hood. Most information about him online is in Japanese, but the real-life Ninkan’s teachings resulted in mass orgies and were soon outlawed by Japanese authorities. It’s claimed he committed suicide by jumping from a mountain in 1114 AD. In the game, he and Sadler attempt to achieve enlightenment.

Pythagoras

Unsurprisingly, he’s based on the real-world ancient Greek mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras, born around 570 BC (which totally throws the in-game timeline out of wack, but it was never accurate to begin with). He’s the guy behind the Pythagorean theorem we all learned at school. In the game he lives in the garden of the Eden surrounded by drunk revellers and naked dancing girls. He provides Sadler with information, and builds a time-machine out of a triangular lake.

Lawrence

A mysterious knight with no recollection of his past, found in the third game. The reason he can’t remember is because he has no past, and was in fact synthetically created by the Ultimate Evil you’re fighting against. At first he takes the role of a boss, but once defeated joins Sadler and becomes playable. He can jump a little higher and swing his axe a little further than Sadler’s sword, but there’s not much difference between them. At the end of the game, because of a belief that he owes Sadler his life, he sacrifices himself so you can save your friends and defeat the boss.

XZR‘s story is detailed, expansive, and hugely confusing to someone who doesn’t know Middle Eastern history. The intro describes the year 622 AD, which is Year One of the Islamic calendar, when the Prophet Muhammad and his followers emigrated from Mecca to Medina. And so history unfolds until we come to 1104 AD, and the birth of our protagonist Sadler, a Syrian assassin who at the age of 20 would take out several key figures, from his father the Caliph who is said to be oppressing the people, to present day leaders. You’re joined by Rumi, Fakhyle, Kindhy and later on supposedly-deceased associate Sufrawaldhi. It’s speculated your group are followers of Aga Khan, leader of a different branch of Shia Islam. There’s also some kind of connection to the Great Seljuq Empire.

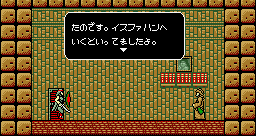

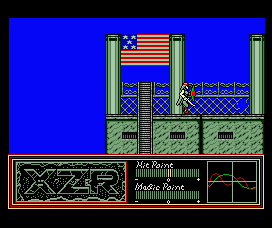

Anyway… You start off near Baghdad, where you search Sufrawaldhi’s grave for a key to enter a prison cell and rescue Rumi. Turns out she let herself get kidnapped to help you. Then you head off to Isfahan in Iran, where people are being killed by the Caliph’s army. Here you buy Kindhy back from the circus and discover Fakhyle’s hidden shack. After helping out the Royal Family there’s mention of the Assyrian Queen Semiramis and then it’s off to Babylon! Turns out Ishtar, the goddess of fertility, love, sex and war, has turned Semiramis into a small bird, and some oil magnate is pumping sludge into the Euphrates River. You also visit the tower of Babel and search for unicorns, then it’s on to Alexandria and a Jewish village, where you get baptised into the faith. Ouroboros needs to be searched for, an erotic book is found, then it’s back to Baghdad. Eventually you reach a major boss, Sufrawaldhi lends a hand (isn’t he supposed to be dead?), and you take out the great Caliph. Here it’s revealed Sadler is his son, having been kidnapped years previously by a band of assassins who raised him as their own. There’s a weird subplot involving a Mongol invasion before Sadler is warped into the 20th Century and fighting modern soldiers. First you take out Russia’s General Secretary, and then America’s President, and then it ends – the world, past, present and future apparently at peace. Or something like that.

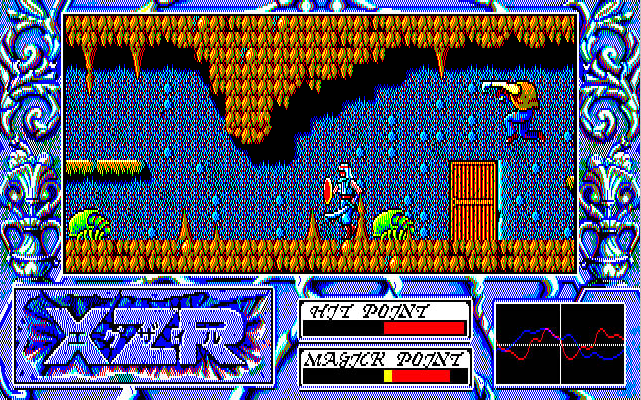

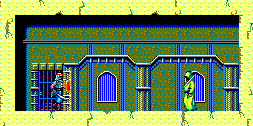

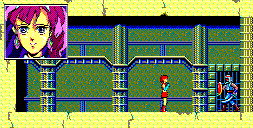

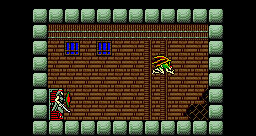

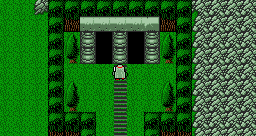

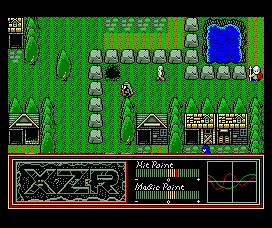

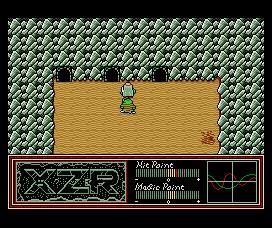

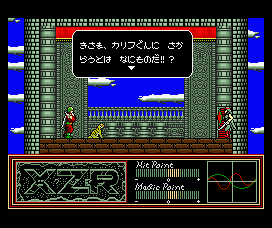

Gameplay is almost identical to the localised Exile follow-ups released on console, alternating between overhead maps where you converse with NPCs, and side-scrolling stages which are unlocked by talking with said NPCs. The overhead and side-scrolling sections can be visited freely as they’re unlocked during each area, but once you progress the story to the next world zone, past stages become inaccessible.

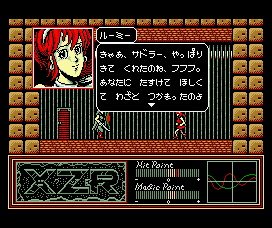

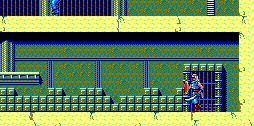

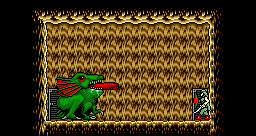

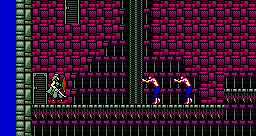

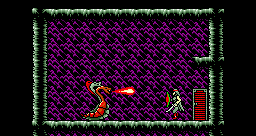

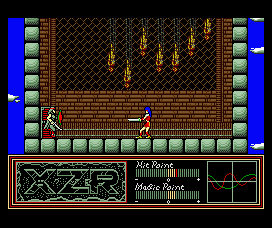

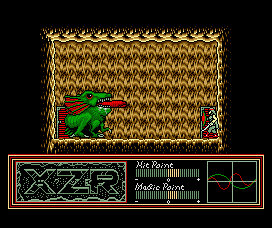

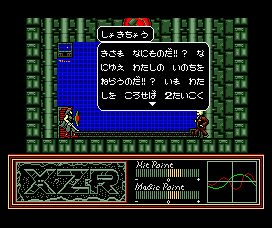

Combat is as you’d expect. Walk, jump, sword attack and, much later in the game, spells that allow you to cast magic such as fireballs and flying serpents. Enemies are generally easy. Occasionally a boss can prove troublesome, but levelling up will make short work of them, and all are weak against downwards attacks with your sword. For action scenes there are HP, MP and two statistics, AP and AC (Attack Power and Armour Class). These have a baseline number that increases through levelling or equipment, and are augmented by two heart-monitor style wavy lines which move and undulate (see the screens). These lines are a visual representation for randomisation during fighting, and while impossible to actually make use of, it’s nevertheless a nice graphical touch. Certainly much better than Morrowind‘s randomised and invisible “why the hell am I not hitting anything” system. It also ties in with the drug-taking mechanic, since in the same way that drugs alter your real-life heartbeat, so too do they alter your statistical heartbeats in XZR, while also increasing or decreasing stats, HP and MP.

Instead of potions or food, XZR features a massive range of drugs, including: LSD, magic mushrooms, datura stramonium, hashish, marijuana, laughing gas, codeine, alcohol, mandrake, cocaine, amphetamines, heroin, morphine, plus a whole other multicoloured galaxy of uppers, downers, poppers and screamers. It makes Hunter Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas look like an E-ride at Disneyland. Despite the quantity available, they don’t have enough of an effect to warrant their usage. New equipment, grinding and clever technique are all far more effective at dropping tough enemies than taking drugs are (perhaps the developers were trying to convey a message here – or perhaps XZR simply isn’t well balanced). They can also cause dangerous side-effects when they wear off, such as stats and health abnormalities, and supposedly even death, though this is rare. To counter such problems another drug called “papuron” is available, which supposedly cancels out the side-effects of other drugs, and at one point there is a rehab centre which normalises your heart waves. The only useful drugs are those which restore HP and MP – all others can be ignored.

Without knowledge of Japanese, and even with the available guides, XZR can be frustrating, even more so because it gives the impression of attempting Tower of Druaga-style shenanigans. Entrances to key areas are sometimes hidden, notably the PC88 overworld map for the Alexandria caves where you need to randomly search walls. Earlier on, when you need to examine a gravestone for a vital key, you need to search on the right hand side of it since searching head-on results in a generic description. Throughout, hotspots are placed in non-intuitive places which are easily missed. Later there’s a frustrating wrap-around mountain maze – not quite as bad as the random maze in Metal Gear, but close enough. At another point an early dungeon is remixed for maximum confusion, and a follow-up dungeon has a puzzle where the boss’ door warps you back to the start (TIP: re-enter this entrance door to warp back to the boss door, and then enter this again – the game is trying to trick you into re-negotiating the entire dungeon). Then there are puzzles where you need to search for a unicorn to make medicine, or buy a flute and drop it in a lake and give it to someone in exchange for another item so you can return to Jewish village and exchange it for a further story item (this side-quest takes ages). And sometimes, even after you’ve spoken to everyone, and examined everything, nothing will happen until you sleep at an inn – which if you have full health, again isn’t very intuitive. Plus, some stores refuse to sell you items until certain conditions are met. If XZR were in English these obtuse “puzzles” wouldn’t be so bad, but when you’re dealing with them and the language barrier, it can prove challenging.

Having said that, XZR is still reliant on action, and the superfluous elements (such as a store which can sell you items using a “credit” system) can be ignored. Most items outside of standard equipment and health items are also useless, existing seemingly only to rob you of your money. To make navigating stores easier, see the translation table below. With the use of online guides, machine-translated into English if needs be, it is possible to make headway, and the game proves fun and tremendously enigmatic – there’s a sense of mystery and the feeling that as a westerner, you’re really not supposed to be playing this game.

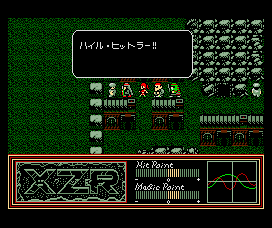

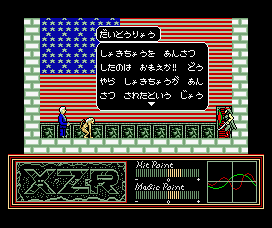

Real-world figures appear in questionable situations, and through understanding only fragments of dialogue a subtle feeling develops, implying that events are both sometimes in bad taste and sometimes a scorching indictment of the real world. An NPC in a Jewish village who shouts “Heil Hitler” is only going to make players feel deeply uncomfortable; an oil magnate who pumps poison into the Euphrates River might raise questions about how we treat our environment and our dependence on oil; and as for the Russian and American leader assassinations, the game was developed during the Cold War – a turbulent time when no doubt many people at some point wished they could put an end to world leaders always bickering. It’s interesting to hold up in-game events against those of the real world during XZR‘s development: for example the democratically elected government of Afghanistan requested the Soviet Union’s support in combating religious extremists in 1979, and only in 1988, the year of XZR‘s release, did they start pulling out. America supported Afghanistan’s opposing Mujahideen fighters during the conflict. In the grand scope of XZR, Sadler seems to be taking on the heads’ of two great powers who, at the time of development, were in indirect but serious conflict with each other and destabilising the world.

Without reading the text in your native language, it’s difficult to make a judgement on how controversial things are. But the game would appear philosophical. There’s a general disdain for organized religion (common to most Japanese RPGs), such as in the first town. If you go to the mosque, the Imam tells you to stay away from the charlatan preaching heresy in the pagan temple at the edge of town, or else suffer the wrath of Allah. However, if you go to the temple, the priestess simply says that you should follow your own beliefs and worship your own god.

Hopefully this feature will encourage fan-translation groups, especially those with some sense of cultural understanding for the settings, to work on a patch for XZR. It would need wit, tact, a degree of sensitivity, and above all a resistance to making changes for the sake of humour or personal beliefs which might be in conflict with the source material. Then we could make a native speaker’s judgement on what kind of statement XZR is making.

Of special note are the differences between the NEC computer versions of XZR and the MSX2 port. The Sharp X1 Turbo version is named in release lists, but the disk image proves elusive and, like a lot of cross-platform titles, is probably almost identical to the PC88 game. The PC88/98 versions use complex kanji for a lot of words, compared to the MSX2 which uses only kana – this ties in with the fact the MSX2 version is easier to play. Perhaps it was aimed at younger players, whereas NEC’s computers were the domain of adult salarymen.

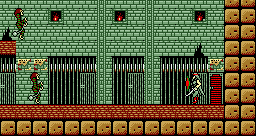

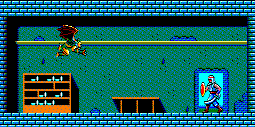

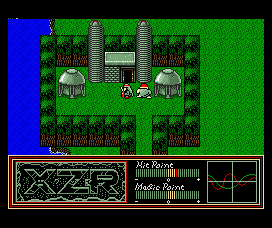

The MSX2 version is hugely different to the NEC computer range, playing like a technologically inferior remix. Not quite as different as the PC Engine and Super famicom versions of Ys IV, but close enough to warrant lengthy comparison. The overhead MSX2 maps use a tile system similar to Dragon Quest, with tiny and poorly drawn sprites, limited animation, and clunky scrolling. The NEC games, which presumably were the base model for the MSX2 port, have detailed sprites, beautifully designed overworld graphics and smooth scrolling, making them reminiscent of the console ports of Exile.

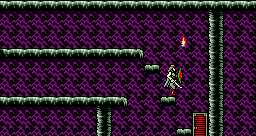

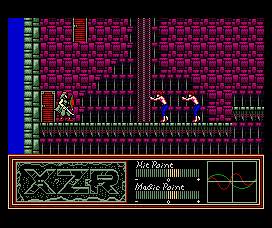

The action scenes are even worse for the MSX2, with small sprites and no horizontal scrolling at all – instead the screen flicks across like a Metal Gear title, scrolling only when climbing ladders. This prove troublesome when enemies are able to freely walk between screens, and isn’t much fun. On the NEC PCs there is full, multi-directional scrolling, albeit jerkily in places, and the pace of the action is fast and exciting, similar to that of XZR‘s sequels. The game is also physically much bigger: to give you one example, early in the MSX2 version there’s a big statue which fits in a single room the size of one screen. On the PC88 version this same statue is about 5 screens tall and the room is 4 screens wide! Playing the MSX2 game is like playing it in miniature. The NEC versions’ scrolling though can prove problematic with fast moving enemies. The bats in Alexandria’s caves for example will follow and trap you against scenery, sapping your health until game over. Larger enemies, meanwhile, will become trapped in small passageways, forcing you to scroll the screen until they reset.

For awhile, it was believed the NEC version was impossible to complete due to a missing item. In Alexandria there is a section where you need to find an alembic (アランビーケ) to progress. Googling the keywords brought up Japanese forums where people were asking the same question. Apparently no one has found the alembic. There were various theories, ranging from buggy code to a devious copy protection scheme, or simply that the alembic is found in a previous area which is now inaccessible. Thanks to turboZII on the Tokugawa forums though, it’s been revealed that the item is just well hidden. At the lower left of Pan the goat god, there is a cave where you can get the elusive alembic.

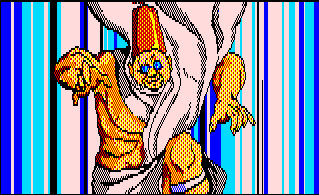

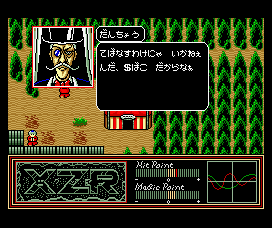

Another disadvantage of the NEC versions is that the side-scrolling levels are invariably dull. Despite the lack of scrolling on the MSX2, they really went to town with some colorful and inventive visuals, which ooze the kind of charm you’d expect from a decent MSX2 game. Note the bandit queen room, which on the MSX2 has dead bodies suspended from the ceiling, whereas on the PC88 is an indistinct turquoise, much like the rest of that dungeon. Only in a few instances, such as when meeting the royal family in the caves, does the NEC version feature more detail. There are also a lot more NPC dialogue portraits in the MSX2 version, such as when the Queen of Babylon is turned into a bird.