Pre-Street Fighter II Fighting Games

|

<<< Prior Page |

|

Page 1: |

Page 2: |

Page 3: |

Page 4: |

Page 5: |

|

Page 6: |

Page 7: |

Page 8: |

Page 9: |

Page 10: |

|

Page 11: |

Page 12: |

After Street Fighter II popularized the genre, 2D fighting games have developed the habit of digging themselves into a hole where only the hardest of the hardcore would really follow them. That's why the genre went into obscurity around the turn of the millennium, and why the spark of live given to it by Street Fighter IV seems to have turned out as little more than a retro fad.

For any game to be popular, it should allow players to immediately enjoy the game regardless of skill level. That, concisely, is what is wrong with fighting games. Due to their complexity, fighters are no longer as easy to immediately and continually enjoy for first timers as they are for veterans. It shouldn't be required to spend hours in a practice mode to get the basics down, or to master the game just to have a good time playing it.

There are also dogmatic design philosophies that keep people away from the genre. Why do they need 720-degrees inputs or weird pretzel motions for special moves? What purpose does this serve? All it does is require players to carry around a dictionary of moves in their heads, for every character in every game. Fighting games no longer allow first timers to jump in and do the basic things that are involved in playing the game. As a result, it's no mystery why 2D fighting games have maneuvered themselves into a niche. For almost two decades, all titles being made are only targeting the hardcore fighting game audience, resulting in a lack of diversity in fighting game design.

But things were not always like they are today. Those pretzel motions? Those were originally hidden moves. They had controller motions which would not normally be performed in regular play for the novelty of the player having to look for the moves themselves. The advanced techniques that certain modern fans of the genre consider to define it? Those were once completely nonexistent. Move cancelling originated in Street Fighter II as a glitch. Extensive combos, also first available in Street Fighter II? That was also an accident. Hit detection and hitboxes were completely different in early fighters as well. Even hit levels and blocking were once not a part of the genre, and even after they were invented there were still games that did not have them. Diversity? Once there weren't any sacred cows in fighters. Designers tried many different approaches to the genre. After certain elements became popular there were still just as many alternatives as there were fighters with the more "modern" gameplay elements.

Then Street Fighter II happened. Most fighting game fans consider the template it popularized and standardized to be the definition of the genre, often not even realizing there were dozens of games before it. It's kind of difficult to imagine today, but SFII sold millions and millions and millions. It was one of the highest selling games of its time. Developers began attempting to cash in on this game and many fighters were made in a fairly brief period. There are about seventy five fighting games for the SNES alone, it being the dominant console during the genre's peak in popularity. Eventually the "point" became about things like comboing and other advanced techniques, for advanced players. Nobody else was really good enough to do them very well or even cared. What did attract people was the basic gameplay.

In a time when the genre was threatened to dry up completely, there is still a series that stood apart in general public reaction. That series is Super Smash Bros. It was among the highest selling series on the Nintendo 64 and GameCube, and proved that the genre could still be popular, separate from the Street Fighter formula. Most interestingly of all, after many years, it is more popular than ever. That is something that no fighter has ever accomplished before. Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat got less and less popular after they took off. Yet Smash Bros. accomplished the impossible in the genre and outlived its novelty.

So that brings us here. Why bother with this history of fighters that precede Street Fighter II? Other than general documentation purposes, to examine all of the influences that led to the creation and popularity of Street Fighter II. This is sort of like how the inspiration for Cave's games was Raiden, which eventually inspired the "bullet hell" genre of shooters birthed by Donpachi. Many of the games listed within are, honestly, quite bad. But each of them is significant in some way or another.

It will be necessary to define the term "fighting game" before going on. In this case, it involves two characters fighting each other, one-on-one, in a confined arena setup. There may be some exceptions of two-on-one or one-on-one-on-one, but any more characters (one-versus-many) becomes classified as "beat-em-up" like Double Dragon and Final Fight. Boxing and wrestling games (including Sumo) are recognized as separate genres, and for good reasons, so they are excluded. Competitive martial arts games and weapon fighting games like fencing will be covered, though.

Working under vector game pioneer Larry Rosenthal - who had built the arcade version of Space War - Tim Skelly conceived the first ever one-on-one fighting game, although it was completed only after Vectorbeam was bought back into Cinematronics.

Like Space War, Warrior provides no AI and thus is strictly a two-player game. All that's displayed on screen are two armored knights holding swords, though some fantasy is required to recognize them as such. The environment is simply an overlay attached to the screen.

Both players control their character with a joystick, holding the single button allows them to freely swing around the sword. As soon as the blade hits any part of the opponent's body, he explodes in a storm of particles. When the two swords collide, the knights are bumped backwards a little, so it's also possible to push each other into the two manholes close to the center.

It's an incredible concept for its time, but the execution certainly betrays its age. The characters move around very sluggishly, and the swords get easily stuck into each other. As the knights turn around automatically to face each other, it's possible to hold the opponent at bay indefinitely just by standing with the blade extended, so many matches are bound to be decided by shoving and pushing rather than any direct hits.

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Designer: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

Warrior (Arcade)

Warrior (Arcade)

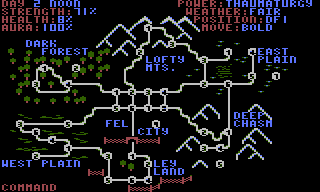

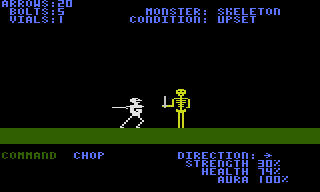

Now, Dragon's Eye was technically sold as an RPG, but as the first game to feature duel fights in the typical side view, it just has to be mentioned here. After selecting a title and a sword, players start out on a map, where they can move around the numbered locations. The quest is to find the eponymous Dragon's Eye within 21 days, but all there is to it is walking up all the dots on the map and pressing the (E)xamine to search the location. Every once in a while, the hero is attacked by a monster, which initiates the combat mode.

This mode is basically turn-based, but the monsters keep moving on a timer if the player doesn't react quickly, adding an element of action to the game. Several offensive and deffensive moves are available via key commands, like (C)hop, (L)eap, (M)agic Bolt, (D)uck or (P)arry, but all the player sees are percentages of their own health and strengths, as well as a vague description of the monster's condition, so it's hard to determine the usefulness of each move. After the fight, it's possible to recharge by taking a rest on the map, drinking vials or using spells, before the quest for the Dragon's Eye goes on.

Dragon's Eye was released for the Apple II, Atari 8-bit and Commodore PET computers (there are C64-ready images floating around, too), which chiefly differ in the way they look. The Atari version is the most pretty one, while the PET with its text character graphics looks worst.

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Designer: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

Dragon's Eye (Atari 8-bit)

Dragon's Eye (Atari 8-bit)

Released in 1982 originally for Apple II computers, Swashbuckler was the first pure fighting game with the side view. It's not strictly a 1-on-1 affair, though: Once the hero has slain one nasty pirate to the left and one to the right, they start appearing in pairs. Their territory on the screen is mostly separate, though, so the player only takes on one at a time.

The system is simple: The character can move, turn around and use one of five fencing moves: The default stance is "on guard" at middle height, but there are also high and low parries to defend against strikes from all directions. Even though these stances are defensive in nature, touching the enemies with the rapier still kills them. "Thrust" is an ordinary attack, while "lunge" makes the hero leap forward while striking.

Like in Warrior, every hit is a kill, be it for the hero or the villains. Every once in a while small animals rush through the screen and go for the protagonist's legs, which has a chance of wounding him instead if they're not fended off by a low parry. An injured hero cannot use the important "lunge" command anymore.

Even though it looks a lot like a modern fighting game, the "one hit kills" mechanic gives it a very different dynamic than most of what came after it. Going back and forth between the two enemies over and over again can grow a bit monotonous, although the game cycles through a few different types with different tricks up their sleeves: While the club swinging brute attacks mostly from above, the peg-legged pirate has a move where he crouches on the floor and tries to stab the hero from below, and the spear-holding foe is capable of rapid advances. The scenery also changes eventually after cutting through a few dozen enemies, although there are only three different scenes. The lack of variety has been noted even in the early 1980s, while the game was most frequently praised for its (at the time) astonishing graphics.

While Swashbuckler was almost an Apple II exclusive in the West (otherwise it only appeared on the super obscure Panasonic JR-200U computer). The game also made it to Japan via Comptiq, where it was ported to the PC-88 and FM-7. These versions technically run in a higher resolution, but they only use it to make the backgrounds look uglier with bad dithering. They seem to have been published as late as Winter 1984/1985, so the game probably didn't have much influence over the earliest Japanese genre efforts.

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Designer: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

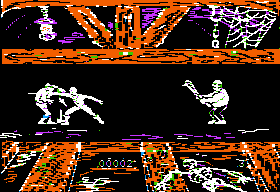

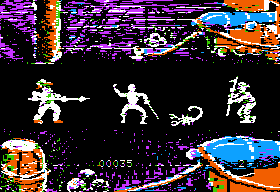

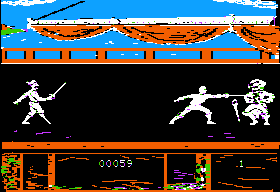

Swashbuckler (Apple II)

Swashbuckler (Apple II)

Swashbuckler (Apple II)

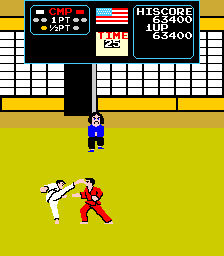

Originally advertised in 1982 by a company called UltraVision, who mostly got attention for the ultimate vaporware console of the same name, Karate is technically the first (non-boxing) game representing a martial arts competition, although it's availability at the time is dubious. It seems not even UltraVision's games for the Atari 2600 properly made it onto the market, although apparently cartridges were produced and got out there somehow, even in several regions under different publisher labels. Five years later, Froggo Games (re-)published the title, the only released fighting game for the console (once again, not counting boxing).

The playing field is more like a beat-em-up and allows the players to move in and out of the screen, as well as back and forth. There are four attacks that are each performed by holding any of the four directions and tapping the lone button. Keeping the joystick in neutral position makes the combatant perform the "up" attack. Matches are timed and each of the four available attacks is worth varying point totals. The competitor with the most points after the timer runs out is declared the winner. Karate, disappointingly, really is a terrible game. The worst part is the hit detection, which almost seems randomized. Controls are horribly unresponsive, and the characters' movement feels awkward, sluggish, and stiff. It might be novel and campy to play a fighter with generic Atari 2600 graphics and audio, but the hit detection and game physics kill it's chances of offering any appeal beyond that.

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

Karate (Atari VCS)

Karate (Atari VCS)

In a way, The Bilestoad is similar to Warrior, but more complex and at the same time more limiting. The controls involve no less than ten keys per player: Three (the middle one is always to stop the movement) turn the warrior around, three are there to swing the axe around, and three to adjust the shield. The last button makes the gladiator run forward.

Despite the medieval weaponry, the duel is supposed to take place in a far future, and thus the warriors move around on a grid atop a field of stars. Quite unusual for a 1-on-1 fighting game, the arenas are huge, and this is where the three little screens on the right come in. They represent different zoom levels when the warriors get too far away from each other. The main screen then swaps back and forth every few seconds, which is extremely confusing, especially since neither of the smaller displays shows which directions the combatants are facing. When one player tries to run away from the other, it's pretty much impossible to catch up, especially since the arenas contain teleporters towards the borders. When the characters are apart, Beethoven's "Fur Elise" plays in the background. There are hardly any Apple II games with music, much less during gameplay, so this was quite impressive at the time.

The name "Bilestoad" is actually a phonetical imitation of the German "Beilstod", a made up compound word meaning "axedeath," quite gruesome for an early 1980s game. Nomen est omen, at least concerning the display of brutality: When the warriors are hit, the blades leave red marks on the body, and blood splatters around and sticks to the floor. It is even possible to hack off both arms of the opponent, who then has to make do with what's left until the end of the match. In an Interview developer Marc Goodman admitted to be inspired by the ludicrously gory fight against the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The degree of violence made it quite difficult to find a publisher for the game, but in the end Datamost of Swashbuckler fame picked it up. Only about 5,000 copies of the game were sold.

In part the shocking presentation might have been responsible for that, and of course the usual piracy problem, which Goodman blamed for the game's lack of success. But all things considered, The Bilestoad just isn't very playable. It only runs at about 2 frames per second, the controls are extremely counter-intuitive, and the large arenas add nothing to the game other than the danger of tedium while trying to find the opponent again.

Since the game didn't do so well, Goodman was done with computer games. Yet in the early '90s, he started programming a remake of the game for Macintosh computers. The game plays pretty much the same as the Apple II version, except at twice the frame rate (not that big of an accomplishment, especially considering the requirement of a 33 MHz 68030 processor). New additions include the map zooming in and out between a few fixed levels (Star Control-style) as the players get farther apart from each other, and randomized objectives for each player (sometimes a match is won by killing the opponent, others by escaping on one of the many face-shaped teleporters). Also present is the ability to select one of four "meatlings" with different appearances and weapons, though this seems to be just for the sake of aesthetics.

Despite not being much of a success commercially, The Bilestoad did have some definite impact on later game developers, though: The creators of the 1997 action adventure Die By the Sword started out with the idea to recreate The Bilestoad in 3D (Game Developer Magazine January 1999, page 62). Another famous fan of the game was John Romero.

(Text about the Macintosh version by Corwin Brence)

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Designer: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

The Bilestoad (Apple II)

The Bilestoad (Apple II)

The Bilestoad (Apple II)

The Bilestoad (Apple II)

Macintosh Remake Demo Screenshots

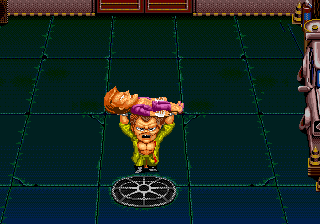

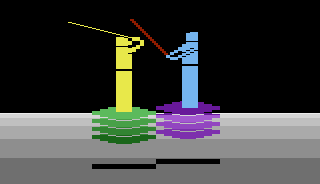

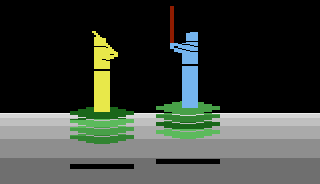

Similar to Karate, this game's history is another odd anomaly: Steve Tatsumi programmed and completed the program around 1983, but MNetworks just shelved it and never published the game. Only seventeen years later, the retro release company Intellivision Productions found itself in possession of the rights. After showcasing it on a few events, frequent demand caused them to produce and sell a small number of copies.

The game itself is also weird, since the fire button is not connected to any attacks, but lets the character hover back and forth a fixed line on a stack of tetragons. The joystick movements encompass three different light saber attacks and the corresponding defenses for each. With every few hits, one of the tetragons get chopped away. Once one of the combatants has nothing left to stand on, the fight is over.

Swordfight only supports player vs player matches, which is assumed to have been the reason for not releasing it in 1983. There's really not much to the game, though, and those who evaluated it at MNetworks might as well have deemed it not marketable for its overly simple mechanics.

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Designer: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

Swordfight (Atari VCS)

Swordfight (Atari VCS)

|

<<< Prior Page |

|

Page 1: |

Page 2: |

Page 3: |

Page 4: |

Page 5: |

|

Page 6: |

Page 7: |

Page 8: |

Page 9: |

Page 10: |

|

Page 11: |

Page 12: |