Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier

|

<<< Prior Page |

|

Page 1: |

Page 2: |

Page 3: |

Reprinted from Retro Gamer magazine (2009), with improvements

Main body re-written by kobushi, based on an old article by John Szczepaniak. Mini-reviews compiled by by John Szczepaniak.

Additional help provided by kimimi, roushimsx, Trickless, Johnny2x4, Karnov, Ben, Danjuro plus several other HG101 and Tokugawa regulars.

Thanks to the Internet, nearly any game of the past can be downloaded and emulated, and almost every piece of information has been documented somewhere... except perhaps the world of Japanese home computers, arguably the last uncharted frontier for English-speaking games enthusiasts.

Japan has long been viewed by the West as a console-centric country, ever since Nintendo and the NES. But there is another, mostly forgotten world of Japanese gaming history, in which thousands of games were developed for various Japanese computers over an 18 year period that stretches from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s. For all that Nintendo started, it was the open hardware of NEC and other companies that allowed small groups to form and become giants. In fact, some of Japan's most recognizable franchises, such as Metal Gear and Ys, actually began as computer games. The early Japanese computing scene was an intense flurry of creativity that launched the careers of many prominent figures in the video game industry, while also establishing some of the most famous video game companies, such as Square, Enix, Falcom, and Koei.

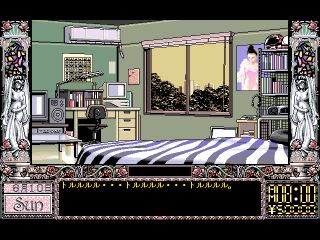

Japanese computer games were also exempt from any of the licensing and content restrictions that all console makers have imposed in various forms. These early games give us a rare glimpse into a world of Japanese creativity unfettered by censorship and outside pressures, which has never since been replicated. The content ranges from rampant drug use and presidential assassination (XZR), to tender explorations of love, sex, and relationships (Dokyusei), to mature and suspenseful horror (Onryo Senki), and even to one of the first rape simulators (177), predating the infamous RapeLay by 20 years. The content is not always tasteful, but the lawless atmosphere resulted in some of the most unique titles in video game history.

Unfortunately, this important part of gaming history has been largely obscured by time and language barriers. If you want to play these games you have to work at it, since they're not easy to find, and rarely described in languages other than Japanese. Until now, most English-language coverage has focused only on the "eroge" (erotic games, or hentai). Erotic games constitute a large and important fraction of the Japanese computer game library, and some are definitely worth your time if you are comfortable with the content, but there are hundreds of other underappreciated titles in almost every genre.

But finding these by games by searching the internet with romanised titles often results in nothing, while using the original names will only bring up Japanese websites which Babelfish renders into lunatic gibberish. Even downloading complete file archives, which are always missing titles due to a lack of definitive listings, will often present you with folders in Japanese characters (assuming your computer can even display them). Finding a good game can become an annoying case of trial and error.

But nothing compares to discovering the holy grail of hearing music and seeing sights few others have, and clicking in that Saturn USB pad for some of the best gaming of your life (and anyone who doesn't own a Saturn USB pad for emulation should be ashamed of themselves). Some narrow-minded purists will frown on the idea of emulating these titles, insisting you should either buy the original hardware or go without. But don't let these sad, misguided fools put you off - with Windows now having a respectable range of highly compatible emulators for just about every Japanese computer that existed, there's little need to struggle with archaic and difficult-to-acquire hardware. Furthermore, emulators benefit from a range of swanky features, such as save states and frameskipping, which are invaluable given how flaky some old computers can be.

A forgotten era

The personal computer industry in Japan began much like everywhere else: as a response to Intel's creation of the world's first microprocessor, the 4004, in 1971. Both NEC and Toshiba successfully developed their own microprocessors in 1973, and over the next few years a number of personal computer kits and homebew packages were released by companies such as Hitachi, Fujitsu, NEC, Toshiba, and Sharp. Much like in the West, these early computers were primarily for electronics tinkerers and enthusiasts, and had to be programmed by the users themselves.

The early 80s saw the release of the first fully-fledged 8-bit computers designed with average users in mind, rather than amateur programmers (although there were still plenty of those). Three companies eventually shared the 8-bit crown: NEC, with its PC-8800 series; Fujitsu, with the popular FM-7; and Sharp, with the X1. NEC would later come to dominate the Japanese computing scene for over 10 years with another computer, the 16-bit PC-9801, but Fujitsu and Sharp were able to maintain a small but loyal following by staying competitive and eventually releasing two incredible 16-bit machines of their own: the Fujitsu FM Towns, and the Sharp X68000.

One important thing to note is that much like the early computers produced by Western companies such as Apple, Commodore, Atari, and IBM, almost all Japanese computers were incompatible with each other. This led to intense competition among the computer makers, with each vying to establish its own architecture as the dominant standard. Once NEC, Fujitsu, and Sharp took the majority of the market, the remaining computer makers banded together around the MSX, a shared computing standard developed by Microsoft Japan and ASCII. Despite being fourth place in the Japanese computer race, the MSX and its successor eventually achieved popularity in South America and Europe, while the Big Three never found success outside of Japan.

Alone at the edge of the world

But why didn't Japan use Western computers, and why does the West know so little about Japanese computers? It's not an easy question to answer, and the various reasons are rooted in economic, technical, and linguistic problems. One problem was simply the fierceness of the market on both sides of the Pacific, making it hard for any company to compete on foreign soil. America in particular became a doomsday market once the CEO of Commodore declared a price war against rival Texas Instruments. In this respect, the early Japanese computing scene resembles the British scene, which enjoyed a similar life of its own.

Nevertheless, most Japanese computer makers did attempt to sell their hardware overseas. NEC had a subsidiary company based in Boston, and presented various computers at American electronics shows in the early 1980s, such as the PC-6001 (rebranded the NEC Trek), the PC-8001, and the PC-9801 (rebranded the NEC APC). In Europe, computers from Panasonic, Sharp, Casio, and Fujitsu were debuted at the 1983 Hanover Messe, and Sharp's MZ series attracted a loyal following. The NEC APC (PC-9801) was even voted the Australian personal computer of the year for 1983. In general, Japanese computers received glowing reviews, as seen in this review of the NEC APC (1, 2, 3, 4), and this review of the NEC APC III (1, 2, 3), both published in a New Zealand computing magazine. Unfortunately, third-party support was a problem, and only a few Western software companies (such as Magicsoft) actively supported Japanese systems. Sales were sluggish, and these early computers were eventually forgotten.

From the Western perspective, Japan was probably more trouble than it was worth. The big Japanese electronics firms already had a tight grip on their domestic market. Furthermore, Japanese demand for personal computers was smaller compared to other countries, due to their perceived difficulty of use, a lack of good software, and the continued popularity of wapuro (i.e., word processors, highly specialized electronic typewriters designed to handle Japanese text). Japanese localization of software and documentation was also difficult in a less international era. As a result, most Western computer makers didn't bother establishing Japanese subsidiaries, and Japan was basically left alone until Compaq burst onto the scene in 1992 with its ultra-cheap IBM PC compatibles. One notable exception was Commodore, who released a Japanese version of the Commodore 64 in late 1982. Unfortunately, the C64 was dead on arrival, thanks to its high price, lack of accompanying software, and compatibility problems with imported titles. Otherwise, Japanese computer enthusiasts dying to get their hands on an Atari 800 or a ZX Spectrum were forced to import one themselves or rely on an independent distributor (such as the early Nihon Falcom). In the late 70s and early 80s, saavy Japanese geeks could also find cloned Apple II boards and other pirate hardware in the small electronics shops dotting Akihabara and Nihonbashi.

The most formidable barrier by far was the problem of electronically reproducing Japanese text. The Japanese written language has three major components: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. Hiragana and katakana are relatively simple phonetic alphabets with 46 letters each, somewhat similar to upper and lower case letters in English. In contrast, kanji is a collection of thousands of complex glyphs originally from China. The sheer number and visual complexity of these characters were beyond the memory and display abilities of most early computers (this is why the specialized wapuro were favored in Japan for so long). For Western languages, a single byte was sufficient to encode most letters and numbers (the US ASCII scheme uses even less memory). But a single byte can only express a maximum of 256 characters, around a tenth of what is needed to adequately display Japanese text. Furthermore, whereas 8x8 pixel blocks are sufficient to clearly display individual characters in Western alphabets, kanji become unreadable blobs without higher resolution. For this reason, any Western computer would require serious hardware modifications to enable full Japanese text support. This remained a problem throughout the decade, until a software-only solution (DOS/V) was developed in 1990. (Apple had created its own software solution in 1986, but it was too sluggish on contemporary hardware.) Meanwhile, Japanese computer makers specifically designed their hardware around higher-resolution display modes to accomodate Japanese text. Remember this, because display resolution became a key difference between Japanese and Western computers, and had a significant impact on game design.

Unsurprisingly, the computer that came to dominate the Japanese market also possessed an exceptionally good Japanese rendering architecture. First released in October 1982, NEC's PC-9801 was a true 16-bit computer with dedicated text VRAM for displaying kanji. A special font ROM was also created to store the thousands of kanji commonly used in Japanese writing. This kanji font ROM was initially sold separately, but came built-in with later models. Two custom graphic display controllers (GDCs) were implemented, one for text and one for graphics, offering a maximum resolution of 640x400 with 8 simultaneous colors (in 1982!). As a result, the PC-9801 could render Japanese text faster than any other personal computer on the market, making it perfect for business use. By 1987, the PC-9801 series had captured 90% of the Japanese market. Unfortunately, marketing strategy and internal politics at NEC caused the PC-9801 to develop a stodgy reputation as a business machine, and games for the system didn't really flourish until the late 1980s. In the meantime, the 8-bit computers were at the center of the burgeoning game industry.

Given this background, it makes sense to divide Japanese computer game history into 8-bit and 16-bit eras, each with its own trinity of hardware.

SPECIAL THANKS

Many thanks to Ben, Danjuro, Peter and everyone else at the Tokugawa forums for providing so much expert help, photos and more information than we could ever print. Also, thanks to www.NFGgames.com and www.pc98.org and for use of images. Thanks also to those on the forums at HG101, SelectButton, NTSC-uk, and anywhere else I've forgotten.

Just as America had its personal computer trinity in 1977 with the release of the Commodore PET, the Apple II, and the Tandy TRS-80, by 1982 a trinity of personal computers had emerged in Japan: the NEC PC-8801, the Fujitsu FM-7, and the Sharp X1.

NEC PC-8801

Launched: 1981

Emulators: PC88Win, M88, X88000

Released as the successor to the PC-8001 (1979) and hobbyist variant PC-6001 (1981), the PC-8801 saw several upgrades and became Japan's number one 8-bit computer, helping NEC to become the dominant force in the Japanese computer industry for most of the 80s and 90s. Originally intended for business use, the PC-8801 was capable of a high-resolution 640x400 monochrome display mode. It was repositioned as an entry-level home machine following the release of the 16-bit PC-9801, however. The PC-8801 series eventually became known for its adventure games and RPGs, and birthed many hits such as Hydlide, Thexder, Xanadu, Ys, Sorcerian, Silpheed, Jesus, and Snatcher. The PC-8801 was also quite popular among doujin circles, and became something of a haven for eroge. Hudson also released several conversions of Nintendo games, including a few awesome originals using Mario!

Sharp X1

Launched: 1982

Emulators: Xmillennium

Originating from Sharp's television divison, the X1 was a surprise product that upset Sharp's earlier MZ-80 series. Featuring a sleek design and various TV integration features, the X1 earned a small but loyal following, especially among shmup fans. Although unsuccessful against the PC-8801, the X1 was generally the better gaming machine and had interesting exclusives, plus several conversions. Often when a game appeared on both, like the original Thunder Force, the X1 version was superior. Collectors should keep an eye out for the X1 Twin, which came with an integrated PC Engine and HuCard slot.

Fujitsu FM-7

Launched: 1982

Emulators: Xmillennium

Originally named the FM-8Jr., the FM-7 was planned as a budget successor to Fujitsu's business-oriented FM-8 (1981). Despite being sold as a cheaper home computer, it could do almost everything an FM-8 could and was technically superior. While unable to shake NEC's PC-8801 from the top of the market, the FM-7 hit a sweet spot of price/performance, and helped broaden the base of computer users. Its successor the FM-77 was backwards-compatible and sported two external disk drives. Later, two further successors were released, the AV (with over 4000 colours and FM sound) and the even more powerful 40SX. Although English information on the FM-7 is still limited, Oh!FM-7 is an excellent Japanese site devoted to the system, with an extensive game database.

These three computers shared many of the same traits. A BASIC interpreter was built-in for amateur programming. Text display was 80 characters by 25 lines. Initially kanji could not be displayed due to the technical issues discussed earlier, and so text input was limited to the English alphabet, katakana, and some symbols. The base graphics resolution was a crisp 640x200 with 8 simultaneous colors. Unfortunately, there was no hardware-level support for sprites, a crucial feature for games. Later revisions would add support for (slow) kanji display, faster VRAM access, and FM synthesis for sound.

Of course, these were not the only computers released around this time. The MSX standard would be announced in 1983 and remained a presence throughout the decade. There was also a strange collection of failures: Tomy's Pyuta range (released as the Tomy/Grandstand Tutor in the West), Casio's PV2000, and Sord's M5 computer range (one of which saw a European release). Plus others which are too poorly documented, even in Japan, to mention.

As the 1980s wore on, the limitations of these 8-bit machines began to be felt, and the balance began to shift towards NEC's 16-bit PC-9801, which had gained an astonishing market share thanks to its popularity as a business machine. Sharp and Fujitsu countered by releasing their own 16-bit models in 1987 and 1989, respectively. With that, a new trinity was formed, and the 16-bit computer era was afoot.

NEC PC-9801

Launched: 1982

Emulators: Anex86, Neko Project 2, T98-Next

As discussed earlier, the PC-9801 was specifically designed to handle Japanese text at high resolution, and became an overwhelmingly popular business machine. Initially its game library was sparse, often consisting of PC-8801 ports such as Laplace no Ma and Record of Lodoss War. However, major updates meant that from 1986 there was a massive jump in quality and greater divergence between the two systems, and over the years the PC-9801 game library would swell to over 4000 commercial titles, not to mention an uncountable number of doujin games. As the dominant computer architecture in Japan, the PC-9801 was even cloned by Seiko Epson, and NEC would remain the market leader until Japanese computers merged with Western standards in the mid-90s. Later PC-9801 models and the upgraded PC-9821 series ran various versions of Windows, making them the best to import. See Tokugawa Corp for an article on buying one (contains one NSFW image), as well as a game database containing more than 3,000 screenshots.

Sharp X68000

Launched: 1987

Emulators: WinX68k, XM6

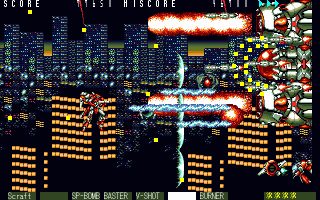

In 1987 Sharp released the – for the time – extremely powerful X68000, an enthusiast's dream machine. Rather than competing with NEC head-on, Sharp designed an expensive but powerful computer squarely targeted at core gamers, programmers, artists, and musicians. The X68000 was so powerful that Capcom used them as development machines for their arcade CPS1 titles. The case was designed in a stylish "Manhattan shape", with separate vertical case sections inspired by the twin towers of New York City's World Trade Center. The X68000 is perhaps best known in the West for its arcade ports and a Castlevania spin-off (later ported to the PlayStation as Castlevania Chronicles). But the X68000 also saw many awesome exclusives, which are now sadly overlooked by Westerners too focused on its arcade ports. Ignore these, since there are dozens of other games you won't find anywhere else.

Fujitsu FM Towns

Launched: 1989

Emulators: Unz

Fujitsu finally appeared on the 16-bit scene in 1989, with a computer that was worth the wait. The FM Towns included a CD-ROM drive as a standard component, along with a mouse-driven OS, 24-bit color, and PCM sound. The CDs were even bootable. With its hardware-level sprite support, the FM Towns was as capable a game machine as the X68000. By 1991 Fujitsu had 8.2% market share, just under Seiko Epson. By 1995 this stake had more than doubled, giving Fujitsu second place to NEC. Fujitsu was also successful in convincing Western developers such as Psygnosis, Infogrames, and LucasArts to port their games to the FM Towns. To this day, these FM Towns ports remain the definitive versions of games like Zak McKracken and the Ultima series. Modern gamers are also blessed with the excellent emulator Unz, which will play most Towns games flawlessly.

Sharp and Fujitsu chose very different tactics in order to compete with NEC's ruling PC-9801. Being the smallest company of the three, Sharp carved itself a specific niche by appealing to hardcore gamers and content creators with the X68000's powerful, arcade-level hardware. Fujitsu instead pursued families and schools with its flashy and versatile FM Towns. Meanwhile, NEC was able to cement its lead with the PC-9801 by forging strong ties with third parties and creating a massive software library. To draw a loose analogy with today's scene, the X68000 was like the PS3, the FM Towns was like the Wii, and the PC-9801 was like the Xbox 360. What resulted was a trio of unique computers with various strengths and weaknesses, and a diverse array of games to match.

|

<<< Prior Page |

|

Page 1: |

Page 2: |

Page 3: |