Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier

|

Page 1: |

Page 2: |

Page 3: |

Japan's 18-year-long computer bubble is difficult to summarise due to poor documentation, excessive hardware variations and an abundance of doujinsoft (hobbyist games). Videogame publishing between 1979 and 1985 in particular was chaos, and some would argue that all games prior to 1985 were doujinsoft.

Many publishing companies in the early days were simply computer shops, with guys programming games in the back, often just as a hobby, and then selling them out front. Nihon Falcom started in 1981 selling Apple computers, before shifting to focus on developing and publishing games. Their first big success was thanks to staff member Yoshio Kiya and his proto-RPG Dragon Slayer in 1984. Most of the blockbusters the company released in the following years were conceived by Kiya. Meanwhile, Koei was founded by the husband-and-wife team of Yoichi and Keiko Erikawa, who mailed out home-programmed tapes to whoever ordered them. Japan had parallels with England's early computer scene, in that if you could program and had a good idea, you could find success. Enix, which always had a good nose for talent, held a contest enticing hopeful bedroom coders. Much like in the West, programming enthusiasts formed informal communities through magazines that published sample code and held occasional programming contests.

Technopolis was a popular Japanese computer magazine, with extensive coverage of doujinsoft at Comiket

Of course, the programmers were bound by the technical limitations of these early machines. The high screen resolution, combined with the lack of hardware spriting found in consoles like the Famicom, meant that creating fast-moving action games was difficult. This in turn led budding game developers to create adventure games mostly involving still images and text. While initially similar to pioneering Western adventure games like Mystery House, they gradually morphed into the kind of minimally interactive storybook adventures now commonly known as visual novels. Also, given the complete lack of content restrictions, these adventure games often contained erotic elements.

The fact is, and this is something uptight commentators in the West have trouble dealing with, eroticism forms a major part of Japanese computer game history. It may be surprising to hear that the first commercial erotic computer game, Night Life, was developed by none other than Koei (click here for an extremely explicit and NSFW screenshot). Other now-famous companies such as Enix, Square, and Nihon Falcom all released erotic games in the early 1980s. In the best cases, the erotic content is meaningfully integrated into a thoughtful and mature storyline. In other cases, the game is just a flimsy excuse for pornography. Sometimes, erotic content will abruptly appear in an otherwise mundane RPG or strategy game, so caution should be exercised when playing in the same room with children or people who would feel uncomfortable.

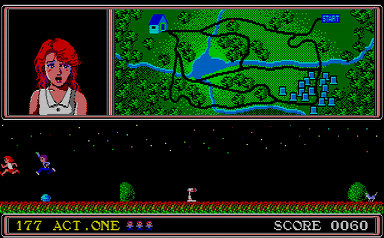

Unfortunately, the proliferation of erotic software did taint the early computer scene in the eyes of the Japanese mainstream. It didn't help that many of these early computer users were still in middle school or high school. In 1986, a game called 177 (the Japanese criminal code for rape) ignited a furor that reached all the way to the National Diet. In 1992, another game called Cybernetic Hi-School (Dennou Gakuen) was declared to be obscene material in Miyazaki Prefecture. Thankfully, the issue was ultimately resolved without enacting laws for banning material. Instead, software makers self-organized and introduced guidelines for the distribution of erotic material, such as applying glittery "18+" stickers to game boxes (these still exist today) and using mosaic patterns to cover genitalia. (That didn't stop some software makers from sneaking in special keyboard commands to remove these mosaics, however.) Ultimately, it speaks volumes for gaming as a medium in the West that only recently have developers incorporated sexual themes into their games, such as Mass Effect, only then to be pounced on by Western news outlets - whereas Japan has dealt with sex from the onset of the technology.

In any case, adventure games became a large fraction of the Japanese computer game library. These slower-paced, text-heavy games may hold little interest for the non-Japanese speaker, but they should not be completely overlooked, because they also showcase some of the best pixel art in video game history. If an emulator such as Anex86 is used in conjunction with the Anime Games Text Hooker (AGTH) software, these games can be even played in (machine-translated) English. Even those who want to avoid erotic visuals completely should not miss out on the many excellent non-erotic murder mysteries and horror games, such as the J.B. Harold series, the 1920 series, and the Nightmare Collection (consisting of Dead of the Brain 1-2 and Marine Philt).

Even with dithering, the pixel art in computer games like Policenauts is simply stunning

In time, clever programming and further hardware revisions enabled developers to create a rich variety of games in all major genres. Game Arts' Thexder was released in 1985, and became the benchmark for commercial quality.

Thexder was especially praised for its music, another aspect of early Japanese computers that deserves special mention. Although the earliest computers lacked any kind of sound reproduction functions besides the tinny beeps of an internal speaker, FM synth boards were sold as optional accessories and eventually built into every model on the market. Almost all of these boards were manufactured by Yamaha and based on a pre-MIDI technology. While not very sophisticated, these FM synth boards produced a warm and pleasant sound, and musicians like Yuzo Koshiro and Takeshi Abo were able to draw out the technology's potential and create music that is still highly regarded by chiptune enthusiasts.

Even after all these years, Yuzo Koshiro remains a prominent champion of this type of sound. Koshiro composed much of his early work for Falcom's games and other titles (lesser known stuff includes music for Misty Blue and the Metroid-inspired The Scheme on the PC-8801), and after moving to consoles he continued to use older hardware. In an interview with Kikizo he explained: "For Bare Knuckle I used the PC88 and an original programming language I developed myself. The original was called MML, Music Macro Language. It's based on NEC's BASIC program, but I modified it heavily. It was more a BASIC-style language at first, but I modified it to be something more like Assembly. I called it 'Music Love'. I used it for all the Bare Knuckle Games." More recently, Koshiro went back to his PC-8801 to create the music for the Etrian Odyssey series. After fully composing each soundtrack on retro hardware, he then transferred the music to the DS sound source (with an unfortunate drop in quality).

Click here to compare Etrian Odyssey's music on the DS and PC-8801 sound sources.

Takeshi Abo has also made some of his early music available for free download.

Doujinsoft continued to flourish alongside commercial titles, and encompassed music and CG collections in addition to full games. The PC-9801 was home to the first five titles in the legendary Touhou Project series of doujin shoot-em-ups. The popular RPG Tkool (RPG Maker) software and its variants enabled even non-programmers to create fully functional games, such as the brilliant and award-winning Corpse Party, which was recently remade for the PSP.

Cing, the company behind Hotel Dusk, was formed from ex-Riverhill Soft employees. Riverhill Soft was an excellent developer of mystery adventure games, such as the J.B. Harold detective series. Later J.B. Harold titles were ported to consoles and released in English, including a couple of obscure Laserdisc releases.

Compile, famous for its Puyo Puyo series, released the Devil Force series of SRPGs on the PC-9801, plus the awesome vert shmup Rude Breaker as well as the 'Disc Station' line – originally for the MSX, these were essentially disc magazines that contained everything from full retail games to staff comments and exclusive bits of artwork.

The RPG tripod of Square, Enix and Falcom all started out on old computers. Square produced quite a few RPGs with very unusual battle systems for the PC-8801, like Cruise Chaser Blassty, featuring a customisable first-person mecha, and Genesis, a Mad Max-style RPG. Enix originally focused on adventure games before finding their niche in RPGs. One notable Enix title was 46 Okunen Monogatari, released for the PC-9801 in 1990. This unique evolution-themed RPG was later heavily revised and released for the SNES under the title E.V.O.: Search for Eden.

Bangai-O's creation is also attributable to Japanese micros, as Yaiman of Treasure told Sega: "Bangai-O started off as a remake of an X1 game called '*****', but then I started to mix in anime influences from Macross and Layzner, and pretty soon it didn't resemble the original, so its being a remake became 120% a bluff/lie. I think the president also liked it, since it was just before the game industry turned cold." While Sega's reporter purposefully blanked out the name mentioned, ReyVGM, Frogcuda and HG101 founder Kurt Kalata all searched the archives until they discovered (with the help of Tokugawa) Hover Attack, released on the PC-8801 and X1, which as the screenshots prove is indeed similar!

Yuji Horii, best known for designing Dragon Quest, started programming on a PC-6001, learning BASIC and then altering the code in commercial games. He went on to create one of Japan's earliest and much-loved graphic adventures in 1983, The Portopia Serial Murder Case (Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken). Portopia is a well-told murder mystery with multiple ways to achieve objectives and a great surprise ending. The Famicom port has been fan-translated into English. Although the Famicom port was more popular, Portopia originated on the PC-6001 and PC-8801, and its semi-sequel, Okhotsk ni Kiyu, received a beautiful remake for the PC-9801 in 1992.

Koichi Nakamura, who went on to program Dragon Quest, achieved his first success with Door-Door in a game design competition held by Enix. Nakamura later formed his own studio, Chunsoft, when he was just 19 years old. An interesting element of Japan's computer history is the number of game design competitions which were run, with several winners going on to become prominent developers.

Yuji Naka's introduction to computers was a Sharp MZ-80, and at the start of the 1980s he bought his own PC-8001, typing in games listings from magazines and improving his coding by finding and correcting the misprints. Several of his favourite games were arcade ports submitted by Koichi Nakamura.

Hideo Kojima was also an early computer developer. The original Metal Gear was an MSX2 exclusive before being ported to the Famicom (NES), and his early adventure games Snatcher and Policenauts were originally developed for the PC-8801 and PC-9801, respectively. The PlayStation port of Policenauts has received a lot of attention recently thanks to the release of a superb translation patch, but many fans still regard the PC-9801 original as the superior version, favoring clean-looking pixel art over blurry console graphics.

Once it shifted away from selling computers, Nihon Falcom became an RPG powerhouse and created some of the best games in Japan, such as Popful Mail and Sorcerian, which made it stateside. All of Falcom's early work was on the PC-8801, and the original versions of many titles, such as Ys, still hold up extremely well.

From across the sea

Even though computer hardware rarely crossed borders, computer software proved to be much more flexible. A large number of Western games were ported to Japanese computer systems, with companies like Starcraft, Infinity, and Pony Canyon focusing almost exclusively on localizing English games. It was a rare time when large numbers of Japanese gamers were actively interested in Western games, an interest which has only just rekindled in the last few years. A little game called Dragon Quest famously arose out of a friendly argument over two Western games. As Koichi Nakamura has stated in an interview, "A game that I have fond memories of is Wizardry, which was popular in our office, but a co-worker of mine named Yuji Horii was hooked on Ultima at the time. Yuji kept saying we should make an RPG, but while I wanted to make a game like Wizardry, he wanted it to be like Ultima. We said to ourselves that we'd combine the interesting parts from both, and what we ended up with was Dragon Quest. So if it wasn't for Wizardry and Ultima, Dragon Quest wouldn't exist -- either in Japan or in the world."

Nakamura and Horii were not alone. The Wizardry ports in particular created a Japanese fanbase for 3D dungeon crawlers that still exists today, despite the sub-genre being long dead in the West. Inspired by Wizardry's template, Japanese computer developers would go on to create a large number of their own 3D dungeon crawlers, often with unique and delightful results. It is this rich heritage that Atlus drew upon to create the Nintendo DS cult hit Etrian Odyssey.

Meanwhile, Western publishers like Acclaim, Brøderbund, Electronic Arts, Microprose, and Sierra On-Line established their own Japanese divisions to publish a wide variety of titles. J-to-E localizations were more sparse, but there are some notable titles, like Nobunaga's Ambition, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, A-Train, and the Metal & Lace series, as well as a number of localized titles published by Sierra, including Silpheed and Sorcerian. C's Ware and Jast also published English versions of their adventure games.

Interestingly, Japanese computers such as the PC-6001 are even where Fred Ford, of Star Control II fame, started out. As he explained (read the full, uncut email, it's very funny):

Fred Ford (left)

"I was attending U.C. Berkeley at the time and was responsible for paying my own way, so I answered a 'Help Wanted' add for a local software company, Unison World. Having no prior experience, when the interview ended with 'We might call you in a month or two.', I figured I was being let down easy.

"But I did get a call in a couple of months. And the crazy thing was that they let me do whatever I wanted, ruining me for later Silicon Valley corporate jobs where my bosses actually wanted to have some say about what I did. First I worked on some sort of Japanese monochrome handheld with a screen about 1cm by 4cm (maybe 16 pixels by 64 pixels). I did a bowling game, a first-person bi-plane game, and a top-down window on a find-the-other-tank game.

"After that I moved onto the NEC, Fujitsu, and MSX. Sometime during this halcyon time, the two owners of Unison World had a falling out and one split off to form Magicsoft. Their agreement had all of the employees, including me of course, going to Magicsoft.

"Some of the games I did for those systems were: Pillbox, Sea Bomber (PC-6001 - pictured), Ground Support, and some submarine game whose name escapes me. I was working on a game for the MSX (I still have the eight inch floppy) when Magicsoft ran out of money. This was just as I was finishing my degree at college and the timing seemed right for me to put away childish things and join the corporate world. Luckily, after six years lost in the corporate wilderness, my senses returned and I hooked up with Paul."

The unconsoled

Of course, the console video game industry had grown considerably during these same years, and the bulging sales figures enjoyed by Nintendo and Sega did not go unnoticed by the computer makers. In 1993, Fujitsu attempted to repackage the FM Towns as a video game console called the FM Towns Marty. Unfortunately, the Marty far exceeded the price of a regular video game console, and suffered compatibility problems when playing games designed with the computer system in mind. The Marty ultimately achieved less than 5% of its projected sales.

Earlier, NEC had made a solid entry into the console market with the PC Engine (TurboGrafx-16) and its numerous extensions. For its successor, however, NEC made a wild attempt to bridge the gap between the computer and console markets with the PC-FX in late 1994. Coming in a tower case with three expansion slots and an optional mouse, the PC-FX was an oddly computer-like console, and looked suspiciously like certain PC-8801 models. The PC-FX could even be plugged into a PC-9801 and used as an external SCSI CD-ROM drive. Even more daringly, the console internals were also repackaged as expansion cards for both PC-9801 computers as well as IBM PCs. With one of these cards, any compatible computer with a CD-ROM drive could be transformed into the PC-FX. NEC even provided software enabling amateur game designers to actually create their own PC-FX games. However, the complete lack of 3D capabilities was a major blow when the PC-FX was compared to the competing Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation. Despite its dominance in the computer world and success with the PC Engine, NEC was unable to attract much third-party support, and the PC-FX was a spectacular flop, much like the FM Towns Marty.

The Fujitsu FM Towns Marty (left), and the NEC PC-FX (right)

Resistance is futile

The early 1990s were a golden age of Japanese computer gaming, with a variety of titles being released on three terrific systems. However, it was also a precarious time for the computer makers, as a number of changes rapidly swept through the insulated Japanese industry.

The first big change was the creation of the DOS/V standard for handling Japanese text. Computing power had advanced to the point where a software-only solution was practicable, and most Japanese computer makers committed themselves to manufacturing IBM compatible machines equipped with DOS/V. Several Western manufacturers also entered the Japanese market at this point, most notably Compaq and its aggressively low-priced PCs. The "Compaq shock" of 1992 was felt throughout the Japanese computer industry, and caused hardware prices to plunge.

A victim of its own success, NEC had become entrenched in its PC-9801 ecosystem, but the global boom in IBM PC clones had led to cheap competition and very cheap parts. NEC was forced to slowly assimilate its computers into the IBM standard until no trace of the original PC98 architecture remained. You can follow the progression of successive PC98 models slowly morphing into a modern Windows PC: the CPU changing from NEC in-house designs to stock Intel chips, to the adoption of the 3.5" floppy disk standard, and then to the more extreme adoption of the IDE bus, SIMM ram, and USB. Starting with Windows 3.1, Japanese text could be displayed at arbitrary sizes, rather than the limited number of fixed sizes imposed by NEC's hardware solution. The specialized hardware configuration NEC had created to speed up Japanese text display had suddenly become meaningless.

But the primary reason for the death of the PC98 platform was Windows 95. As the first operating system that truly provided seamless support of both English and Japanese software, Windows 95 enjoyed the biggest launch of any software product in Japanese computing history. Moreover, games designed for Windows 95 would run in Windows 95, regardless of the underlying hardware, which meant that NEC's proprietary technology became completely irrelevant. By the end of 1996, the glorious era was over.

During this upheaval, game developers were faced with a choice: to continue with the computer platform, or switch to the larger and more lucrative console market. Most chose the console market, and many ports of Japanese computer games can be found on the Saturn and the PlayStation (at lowered resolution and censored, in most cases). On the other hand, developers committed to creating content unsuitable for consoles (such as eroge and complex military strategy games) stuck with the PC, where they remain to this day.

Hidden threads

With all of the above proving the importance of Japanese computers, it has to be asked: why aren't they archived online, like say the Spectrum? Well, they are, but the files are tucked away into deep and dark corners of the Internet. The majority of games were dumped in the 1990s and shared on BBSs and message boards, often embedded inside JPG images to deceive automated servers which would otherwise delete ZIP and RAR files. Nowadays, p2p networks are the preferred distribution method, but Japanese p2p software goes to great lengths to maintain deniability and anonymity, and can be frustrating and difficult to use. Overall, the Japanese retro scene is a much more private and cautious place than the free-wheeling nature of Western sites like the Pirate Bay.

The main English source for anything to do with Japanese computers is the Tokugawa forums, which I visited for information. Another reason for lack of downloads, as one insider reluctantly told me, is that about a decade ago, prior to Tokugawa's formation, there had been a collaboration between East and West to dump and share Japan's retro computer games. Except the games ended up being sold online by one of the Western members... Apparently, Japan has yet to forgive this treason.

I asked Tokugawa's founder, Ben, about some of the other difficulties found in the scene. He explained, "You have to know how to run a DOS game using Japanese DOS; how to install a Japanese game on a virtual HDD from several floppies; run a game in basic mode, since sometimes that game was originally a tape, and the list goes on and on. TOSEC tried to establish a data-set for several Japanese retro computers, but for some games, just because the save file on disk 12 was changed by 2 bytes, we ended up with another set for the whole game. There is a wide variety of dump formats for almost all machines, well over 10 for PC98, and emulators don't come with English directions."

Tokugawa's resident PC88 expert, Danjuro, also spoke about the difficulties in dumping games, explaining that you need a 5 and 1/4 inch Amiga drive to read the floppies correctly – many also need to be cracked afterwards.

Other members also answered questions, and everyone shared software freely. But there's a sadness visiting the Tokugawa forums, as you realise that all the hard work in collecting over 5,000 scanned covers and manuals, screengrabbing various games, plus dumping, renaming and organising the thousands of games themselves, all falls to the callous whims of ImageShack and RapidShare, and that the vast databank of knowledge accumulated over hundreds of forum pages is all at risk of a Home-of-the-Underdogs style disappearance. Were it not for the relentless hard work of these few fans, there would be little online in English regarding the history of Japanese computers and the games which you will find nowhere else.

Rusty (PC-9801)

Usagi na Panic (PC-9801)

A-Train (FM-7)

177 (PC-8801)

Cybernetic Hi-School (Dennou Gakuen) (PC-9801)

Thexder (PC-8801)

Loop (PC-9801)

Corpse Party (PC-9801)

J.B. Harold: Manhattan Requiem (PC-9801)

Disc Station 98, a disk-based magazine for the PC-9801

46 Okunen Monogatari (PC-9801)

Sorcerian (PC-8801)

Popful Mail (PC-8801)

Wizardry (various, PC-9801 version pictured)

Genesis: Beyond the Revelation (PC-8801)

Steel Gun Nyan (PC-9801)

Sea Bomber (PC-6001)

Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken (PC-6001)

Silpheed (PC-8801)

DAIVA (various)

Rogus (PC-9801)

Genocide 2 (X68000)

Star Trader (PC-8801)

XZR (Exile) (PC-8801)

Various Game Screenshots

|

Page 1: |

Page 2: |

Page 3: |