A History of Korean Gaming

Part 2: The rise and fall of the package

Gaining respect

On February 20, 1994, a former Soft Action employee called Kim Hakkyu started to upload a series of postings on the online service HiTel, titled "[Facts] What we'd like to know - Mr. Nam Sanggyu," in which he commented upon the working conditions experienced in his short time with the company. For the first time the average gamer could get a - less than flattering - insight into the newly risen industry that had seemed so vital and prosperous in recent times. Complaints about masses of unpaid overtime, poor and much belated payment, but also a lot of personal quarrels with the president started popping up from several sources.1 Accounts that blamed Nam Sanggyu to have poisoned the food at the company2 were certainly greatly exxagerated, but the scandal's nickname "Dog Food Incident" speaks volumes. In the following trial it appears Kim Hakkyu was convicted for slander, but the damage was done. While from today's perspective it appears impossible to determine the true circumstances, the truth was likely to be found somewhere in the middle. Kim Hakkyu's original postings seem to be lost as well, together with the online argument that followed. Certain is that the developer who only two years before had been hailed as the savior of the industry had lost the faith of the customers beyond repair and continued to sink more into obscurity with every following title released, making way for a newly emerging generation of young enterprises.

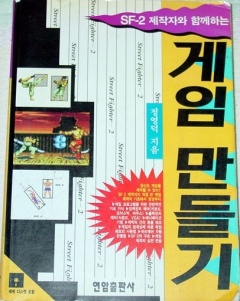

One of the most popular early freeware

games was the unofficial PC version of

Street Figther II - programmer Jung

Youngdug even wrote a book on

the creation process

Two of the more famous upstarts of these days were TWIM and Family Production, both entered the market in late 1993 with quickly forgotten sidescrolling action adventures. They only found success the following year with more arcade-like games. TWIM became most successful for the Tonko series, while Family Production's first big hit was the cutesy beat 'em up Pee & Gity. On the financial side, things remained miserable at first, though. Jeong Jaeyeong, founder of TAFF System, which soon became famous for its fishing simulations, had worked on Sengoku Denshou at SNK in 1992, when the company was at the top of its game, the Neo Geo still fresh and continuing to blow everyone's mind. Back home, on the other hand, he had to program the first game of his own company on a computer borrowed from a friend's mother.3 A game that managed to sell more than 10,000 copies still had to be considered a hit, and games still had to be crunched out within months to make a profit, semi-regular office hours and a regular salary was far from being the norm. Trigger Soft's Jeong Musik remembers: Until 1997 I hardly ever received a proper salary, it was not until 1998 when I started regularly getting about 700,000 Won a month."4 Teams rarely consisted of more than ten members in these days, and most of the time were recruited from among independent developers.

BBS played an important role in the formation of these teams. Unless aspiring game makers were blessed with like-minded high school friends, they had to organize through these networking services. Cho Younggee, Choe Yeonkyu and Jeon Seokhwan had met at a console gamer's club meeting and formed a team called "Art and Technology," before being joined by Kim Hakkyu and Kim Seyong. The resulting Artcraft Team became the cradle of many of Korea's most influential game designers: While developing their first game Lychnis, the "Art and Technology" faction joined the now famous company Softmax, while Kim Hakkyu and Kim Seyong (accompanied by another Artcraft member, Chae Jaehyeok) went on to form Gravity Software, of Ragnarok Online fame. Most staff members of Mantra's Ys 2 remake were likewise drafted from these game clubs by Son Seoho. TeMP, the famous group of freelance composers now known as SoundTeMP, also first operated through the BBS service HiTel.5 Later teams that made the amateur-to-professional transition were Garam & Baram, who met through the network and ended up moving to Busan together, to join the established software house Mips, or the lesser known Byteshock (started out with an unofficial homebrew PC port of Taito's Kiki kaikai before getting published with Electronic Popple), Acro Studio (known for the shooter Baryon, which also made it to the West as shareware), Dream Card (made it from the freeware game Moheom Sok-euro to the commercial product Black Sign) or Object Square Team (Astrocounter of Crescents), whose leader Kim Donggeon later created the Mabinogi series of Online games.

With the growing homebrew scene also came the demand for a proper education of young talent, which was initially met by only two educational institutes: Goldstar Soft founded the very first course for game producers and graphic artsists at the Goldstar Education Center in March 1993,6 the Softry Game School followed just five months later.7 Both relied on industry "veterans" for their teaching body: Goldstar Soft hired Soft Action developers,8 while Game School teachers were recruited from the short-lived team KETO (which consisted of former Daou Infosys staff).9 Many later important figures of the industry got their education at one of these two institutes. By 1997 Gameschool counted Jeong Bongsu of FEW, the Dragonfly team and SiEn Art's Pak Cheolho and Hong Gyeongcheol to its alumnis.10 Game School is in operation even today.11

The next step for the industry was to get more closely networked and organized. For the coin-op industry the Korea Electronic Amusement Center Association (한국전자유기장업협회, renamed to Korea Computer Game Industrial Association 한국컴퓨터게임산업중앙회 in 1994) had existed since January 1985 to self-regulate arcade game import under the administration of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.12 In June 1993 it had just elected Kim Kaphwan, himself leader of the Viccom group of 3 arcade game developing and publishing companies, as its fourth chairman.13 As kind of a rivaling organization stood the Visual Entertainment Creators Association (영상오락물제작자협회), whose chairman Kim Jeongryul, also the owner of the company Windeal (later Deniam), did a great deal of lobbying work at the Ministry of Culture and Sports (now Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism). After getting the admission by the Ministry on March 29, 1994, it held its founding ceremony on May 5. 45 companies united under that banner, including Windeal, Dooyong, Unico and Comad.14 Consumer game publishers in the meantime formed under the banner of the Korea Electronic Pictures Culture Association (한국전자영상문화협회), lead by Dongseo Interactive president Yun Weonseok and encompassing 61 companies, including big shots like Hyundai, Goldstar, Ssangyong and SKC.15 The organization was founded in February 1994 and started operations in April, with the fight against piracy as its major objective.16

Apparently all these organizations started getting a bit much even in the eyes of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and so in September 1996 it strongly suggested the merging of the Visual Entertainment Creators Association and the Korea Electronic Pictures Culture Association, supposedly to cut down on the rivalry and factionalism between the different industry organs. The combined organization kept the name of the former, while Yun Weonseok of the latter remained as its chairman.17 The rivalries continued, though: When the KGIA was involved in bribery investigations and had its approving authority for arcade games revoked, voices became loud that claimed an intrigue by Kim Jeongryul was the driving force behind the investigations, in order to gain control of the approving process for his organization.18

Relatively unaffected by all this was the Korean PC Game Developers Association (한국PC게임개발연합회, KOGA), which was formed in October 1994 (it might or might not be related to the Korea Game Developer's Association, an alliance of small software houses and indie developers that held a preliminary meeting in the Korea Software Plaza on June 5, 199319) by Mirinae Software, Twim, Softmax, Makkoya, and Family Production with TWIM's president Choe Gwonyeong as its first chairman. Many more companies joined the association over the years, predominantly small independent studios, until LG Software's entry in 1996.20

Contrary to the other, publisher- and distributor-driven organizations, KOGA was formed in order to strife for a more developer-friendly publishing environment.21 Early on it released a compilation of Makkoya's Super Segyunjeon, Mirinae's Apachacha and Twim's Father World on CD-ROM,22 which was only a prelude to the founding of an independent publishing company on September 20, 1996.23 Much like the later Gathering of Developers in the US, it was conceived as a developer's publisher with fairer conditions. It also organized the Korean delegation to the ECTS '97, and published the very first White Paper on the Korean video game industry.24 Unfortunately though, it was even more short-lived than GoD.

The same small companies also got together for the first dedicated video game Expo in Korea - so far companies like Samsung had showcased their gaming products on the Korea International Exhibition Corporation (KIECO)'s events. Organized by the Korea Information Culture Center, the first Computer Edutainment and Game Software Festival was held February 24-27, 1993 at the electronics store complex at Yongsan, Seoul.25 While stress was put on the "edutainment" part, the stated goal by the Information Culture Center's PR section chief O Seungsu (吳承洙) rather seemed like an conservative attack on video games at first glance: "The game software currently used in this country is imported indiscriminately from foreign countries; most are violent and obscene products that inspire worries about our children's emotional development," but it becomes clear that this was only meant to discredit foreign games in favor of boosting the fledgling domestic industry, as O continues: "With this event we're envigorating game software companies in this country and provide the environment for the development of the industry."26

The festival was held annually at least until 1996, but after the first one could still rely on the pull of high profile exhibitors such as Hyundai Electronics, and still had the support of the Electronic Pictures Culture Association until 1995,27 in the end the event fell into obscurity, to the point where it was only carried by the small KOGA membership developers,28 without the big shots taking much notice.29 The demise of the festival was probably the result of it being outclassed by the Amuse World expo, first held from December 16 to 19, 1995 by the Visual Entertainment Creators Association.30 Although it started out quite humbly as well - in its early years, it had to share its show room floor with the General Pictures Festival (종합영상축전) of the movie industry,31 but it kept growing steadily, eventually evolving into the G-Star expo in 2005, still the largest game industry event in Korea.

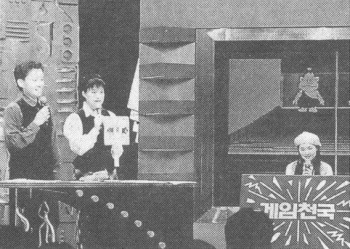

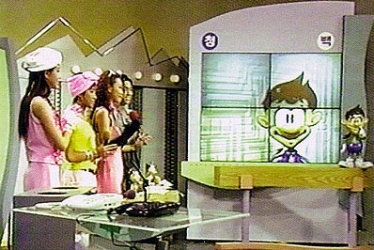

It seems in the late 20th century a new medium hadn't really "made" it until it was featured on the dominant old medium, the TV. For video games in Korea, this moment came in 1994 with the start of two call-in game shows. The live broadcast Game Paradise (Game Cheon'guk 게임천국) TV-i on KBS 2TV started the trend, first airing on August 14. The software for initially 8 mini games was provided by Mirinae Software and Tapcom, who also took care of putting the technology in place. Some of them were made for two players to compete with each other.32 The show not only entertained call-in players, though, but also studio contestants. There were games made specifically for the program, but also some retail games like Family Production's Into the Sun. Later this was even expanded to foreign games like Sega's Daytona USA and the seemingly unfitting Sim City 2000.

SBS' Coba on the Run (Dallyeora Coba 달려라 코바) followed on October 24. DS Game Channel programmed the games, which it also bundled and sold in packs as releases for PC.33 It was almost a carbon copy of the Scandinavian Hugo show, complete with charming young female host and some of almost the same games. Both shows were highly successful, Game Paradise even managed to take down the phone network in the provinces due to several thousand simultaneous callers.34 With 17%, its ratings weren't quite as high as Coba's, though, which made it to 22% in the ratings at a 36% viewers quota.35 It is uncertain how long the shows ran, but each can be traced until 1996, when they were joined by a third show named Narara Hoking (날아라 호킹).

Another major step in getting accepted as a serious industry was very particular to the political situation on the Korean Peninsula: The option of applying for military service exemption for developers. Every male South Korean is required to serve in the military for two years, and is effectively taken out of civil life for the duration. The main programmer getting drafted during crunch time undoubtedly is an enormous blow to any game in full production. While it was technically possible to apply for military exemptions before (as the developer TWIM sucessfully did in 1993 after the drafting of staff members caused a severe delay of its debut title Father World), the procedure was only explicitly acknowledged in April 1994, when - under the umbrella of New Technologies - game software developers were officially encouraged to do so from July 1 to 25.36 Getting through all the bureaucracy and formalities remained quite an ordeal, to intercept possible attempts to merely dodge having to serve, and there were always severe application deadlines to follow.37 Independent teams that were not part of a properly established company of course couldn't hope to get a slice of this pie either, and there are many cases of people switching teams/companies for the exemption,38 but it was a first small step of the govermnent reaching out to the fledgling industry and offering at least some form of support.

The Ministry of Culture and Sports became even more generous in 1996, when the first Korean Game Awards were announced. Named "Game Grand Prize" (Game Daesang 게임대상), it was mostly the result of the Visual Entertainment Creators Association's lobbying, who closely worked with he ministry on this. The prize was initially awarded in two categories, for finished games and for game scenarios, and endowed with 5 million Won prize money.39

The death of consoles

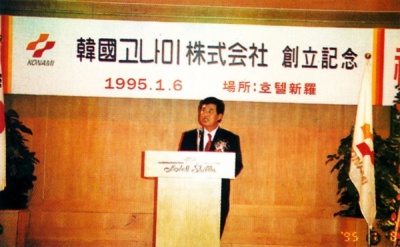

But what happened to the home consoles while the PC prospered as a platform for Korean games? Their fate is actually one piece of Korean video game history that has come up numerous time in the Western media, when it came to try and explain the current, MMO-dominated state of the industry there. Almost every account, however, was fueled by misconceptions and oversimplifications. Richard Garriott, back when he was developing Tabula Rasa and still excited to work with the Korean company NC Soft, declared: "Korea, for decades now as a vestige of World War II, has had a law on the books that dissuaded companies from importing goods from Japan. Game machines from Nintendo, Sega, and Sony have been effectively banned, (...)".40 By now we all know that this couldn't be further from the actual state of things, as both Nintendo's and Sega's consoles have been readily available throughout the 90s. Even Japanese companies establishing subsidiaries in Korea wasn't unheard of. Fujitsu for example was in Korea since 1974, then under the name FACOM Korea.41; Sharp entered even a year earlier. As far as game companies are concerned, Konami established a Korean branch in January 1995,42 which ended up publishing a handful of arcade and N64 games until 1999 (and is not directly related to Konami Digital Entertainment Korea, which was founded in 2008).

Even Jim Rossignol in his - otherwise fantastic - article on the current pro gaming scene in 2008 stumbles over the vague explanation attempts by his Korean informants when he declares "early generations of Japanese game consoles prohibitively expensive for Korean gamers"43 due to trade restrictions between Korea and Japan. Trade restrictions were indeed in place, but, the price difference between consoles and PCs was at no time significantly different from elsewhere in the world.44 As a matter of fact, both Samsung and Hyundai eventually went on to assemble Super Gam*boy and Comboy consoles, respectively, in Korea, presumably circumventing most of the import costs.45 The sales of licensed Japanese game consoles kept going well in the first third of the 1990s. Samsung sold around 200,000 consoles a year, and Hyundai was catching up fast with their Comboy series.46 In November 1992, the Kyunghyang Shinmun estimated 1.5 million consoles sold in Korea by then (probably including Famicom clones), which would mean there was one console in about every eighth to tenth household.47

There is really no single factor that can explain alone why consoles withered away in Korea. Their demise rather came in several steps. The first big obstacle for the thriving industry came in the form of epillepsy hysteria. This phenomenon swept over the western world as well in 1992-1993, but in Korea the sensationalist mass media were particularly successful in doing what the media do best - induce disproportional mass panic, to a degree that would have sufficed to make people perceive epillepsy among kids in Korea like an epidemic. On a daily basis during the second half of January 1993, newspapers tried to outdo each other in reporting alleged new cases (even a fit from a mere casual onlooker in an arcade was reported48), digging out old incidents and retroacively connecting them to vigeo games49 or simply printing more opinion pieces on the matter, all long before the original incident that sparked the hysteria was even conclusively examined,50 resulting in mass disposal of children's game consoles through their parents.51 Now anti-Japanese sentiments also started creeping into the argument from conservative outfits, as often the newspapers stressed that the initial reported cases in the US and Canada were caused by Japanese game consoles,52 or appealed to the morality of importers.53 The English language paper Korea Newsweek likewise printed:

A Seoul boy has been hospitalized after losing consciousness while playing a Japanese-made video game. "The boy lost consciousness after being overwhelmed by epileptic symptoms last week while playing 'Street Fighter II' produced by Nintendo, a Japanese video game maker", said his father Kang Yong-yol.

This news also came with a disclaimer that should have served to keep overly hasty reactions in check:

[Experts] maintain that more Korean youngsters have epileptic fits in discotheques, where they are exposed to loud noise and fast light movements than while playing video games.54

After all that hysteria it finally turned out that the boy's epileptic fit wasn't related to flashing light sensitivity at all,55 but the damage was done. Contemporary newspapers reported that sales had gone down to less than 10% of the usual within January,56 although over the year the situation relaxed just a little bit: Samsung reported later that their 1993 sales meant a decline by 71.4%, from 185,000 to 53,000. Hyundai sold 52,000 systems (decrease by 33%), Haitai 35,000 (down by 59%). Some smaller famicom clone manufacturers like Cosmotech and Daou also reported a decline of 50%.57 Console distributors like Haitai reacted with including "protective glasses" with their products (newspapers had earlier urged parents to make their children wear sunglasses and turn down the brightness of the TV during play58), and games by the few Korean console developers started to feature automatic pause functions after an extended play time.

The impact of these events on the industry was grave, but not unsurmountable. The market soon started to slowly recuperate, and especially Hyundai's Super Comboy (rebranded SNES) was doing extraordinarily well. Yet the next blow was just waiting around the corner: A revision of censorship regulations for popular media, enacted by the Ministry of Culture and Sports on July 1, 1993, demanded that video games on CD-ROM or cartridge, just like other "audiosivual" media like movies and music, be submitted for evaluation through the Korea Public Performance Ethics Committee.59 In the early days when the committee lacked members with any experience in handling this new medium, there had been lots of confusion and decisions that were hard to get behind even during the time. Among the games that were refused a rating during these days were Gunstar Heroes, Bare Knuckle 3 and General Chaos.60

The rating system continued to be one of the strictest throughout the free world during the 1990s - Germany is well known for having violence in games reduced, but after submitting the German censored version of Resident Evil 2, publisher Ssangyong was forced to even more concessions to get the game through the mandatory procedure.61 Western games like Duke Nukem 3D,62 Diablo63 and Dungeon Keeper64 didn't make it through the inspection unscathed, either. Even Aeris' bloodless death scene in Final Fantasy VII was censored. StarCraft got distributed in a heavily censored "Teen" version alongside the 18+ uncensored game,65 and its expansion Broodwar had even more trouble getting released.66 Erotic visual novels from Japan in the meantime were stripped of all explicit sexual content.67 Korea's game censorship put strict boundaries to both worlds - sex and violence. It was not only foreign games that had to deal with this: Triggersoft's organized crime simulation Boss was only waved through after all gangster terminology and real-world place names were removed.68 On the opposite side, sometimes Korean games were even sexed up for a possible release in Japan. Ecstasy Entertainment prepared special nude scenes for their otherwise fairly tame raising sim Newly Weds,69 and the innocent fantasy SRPG Xenoage was remade as a full-on eroge with the title Kaze to Daichi no Pageant.

The reason console games were hit much harder by the new rating system, however, was one particular side-effect that came with the law: In result of the troubled history between Korea and its insular neighbor, it was illegal to distribute mass media in Japanese language, and games had just been elevated to the same level of scrutiny as movies and TV shows in this regard. Thus by January 1994 games with Japanese screentext were effectively banned.70 Both Samsung and Hyundai had a stream of simultaneous releases with imported Japanese games running since 1992,71 but now this was to end. The console publishers dodged to English US versions of games,72 but the most important genre, the console RPG, wasn't exactly in rich supply in the West. Waiting for the English localizations also meant losing time to illegal importers. The two conglomerates' remedy was a handful of localized games: The Super Alladin Boy saw Korean versions of Crusaders of Centi, Light Crusader and The Story of Thor, while Super Comboy fans had to be content with the sports games Korea Pro Baseball and Tae-Kwon-Do.

Furthermore Samsung - who had already developed the original Mega Drive shoot-'em-up Uju Geobukseon in 1993 - conspired with Korean developers to get a stream of Korean exclusives to their console. Initiated in September 1994 and funded with 6 billion Won,73 the Samsung Game Soft Group (short SgSg) was a pact with 8 (later the number was raised to 15) smaller companies to develop titles for Super Aladdin Boy and Pico74 (which Samsung also published in Korea). The list of developers included Open, HiCom, Softmax, Softry,Sailon, Digital Impact, Mantra and Soft Action,75 and no less than eight games for the 16-bit console were promised.76 The named titles were HiCom's If and Powerball, Open's EXP and Super Toema Yeongung Jeon'gi ("Record of the Super Exorcist Hero"), and Softmax' Halloween Capsule. Many of them were reportedly completed or almost completed77 before Samsung suddenly pulled the plug and cancelled all of them in late 1995, presumably to put all the budget into promoting the new Saturn.

That was a mistake as it turned out, because every released console from now on was doomed to fail on the market. In late 1994, almost a year before Samsung brought over the Saturn, Goldstar got heavily invested in the 3DO adventure, building and publishing its own variant based on the 3DO specs, the Alive. (Samsung at one point was also developing games for the system, but abandoned it even before the Korean version was released.78 Even though Goldstar actually managed to get together developers and deliver some Korean exclusives - the US-developed FMV shooter Firewall, the 2D fighter The Eye of Typhoon, a turn-based tactical game called Battle Blues and the in-house developed space sim shooter Armageddon - the system was just as much a failure as it was everywhere else in the world. Throughout 1995, only 20,000 units were sold.79 Goldstar (by now renamed to LG) tried to turn its fate witch a more slick and cheaper second hardware model, but that one is so rare some even question if it was ever released, despite being advertised with a price and a set release date. LG officially abandoned the 3DO in late 1996.80

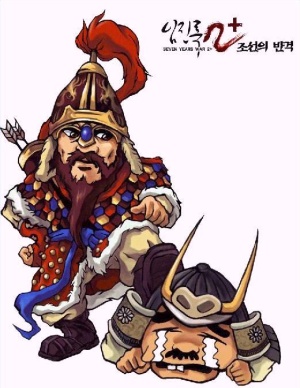

The marketing campaign for Imjinrok 2+ rode the

wave of protest against the misrepresentation of

historic facts in Japanese school books.

There are no thorough statistics available for the Saturn, but within the first month after its release, it sold a mere 2,000 units.81 The console was incompatible with the Japanese version, and retailed at W550,000 Won, the highest price tag a console in Korea ever got, which should explain at least some of the customers' reluctance. Incidentally, the Saturn was the first console to receive third party localizations. A handful of games were actually officially localized through Wooyong System, an arm of the Japanese company AIL. The released titles include Myst, El-Hazard The Magnificent World, Albert Odyssey Gaiden82 and Impact Racing.

All of this didn't help. Even though multimedia market analysts at the end of 1995 esteemed the value of the industry to almost double by 1997,83 home consoles had started to almost disappear from the Korean gaming landscape by the end of the 1990s. While Hyundai still released the N64 in 1997, the new world market leader was only seen in import shops, as no company ever picked up the PlayStation for a proper release. Daewoo had been in negotiations with Sony to get back into the console business,84 but never followed through.

The Dreamcast's fate in Korea is a bit more complex. The Hyundai conglomerate and Sega had actually founded the shared subsidiary Hyundai-Sega in 1996, to setup a chain of arcades and distribute Sega's amusement machines. October 1998, this company decided to bring the Dreamcast over as well.85 By late 1999, Hyundai-Sega claimed to be almost ready for launch in early 2000. The system was supposed to be region free and cost no more than W200,000, seemingly circumventing all the issues that had plagued the "next gen" consoles that came before.86 In May 2000, the system still wasn't released, and the ambitions had been downsized to a direct import of the Japanese hardware.87 In September that year, Hyundai-Sega announced that it had given up bringing the Dreamcast to Korea after being denied an import license.88 (One assumes the reason might have been the Japanese language option in the system's bios.) This makes the Dreamcast the only console to not appear in Korea specifically because it came from Japan - at least that was the official story. Sega's being on the verge of discontinuing the Dreamcast probably played a role as well.

An Xbox promotion event at the World Cyber

Games 2002. (photo: Gamedonga)

This happened in a very odd time frame, too: Just in October 1998, President Kim Daejung had declared the gradual opening towards Japanese mass culture. In its third step on June 27, 2000, the program lifted the ban on the unaltered import of all Japanese games except console games. At this point, Power Dolls 4 on the PC could be published with Korean subtitles and the original Japanese speech, but on consoles this was still impossible.89 It seemed as if those would follow suit soon, but a conflict about the misrepresentation of historical facts in Japanese school books brought everything to a complete halt, and only after the success of the shared soccer world cup in the two countries, Japanese culture imports - including console games - became entirely freed from any bans on September 16, 2003.90 It should be once again stressed that this ban ever only affected Japanese language in imported goods, not properly localized software.

In the new millennium, home consoles managed to win back a little more footing. For reasons further elaborated on below, foreign console manufacturers then entertained their own subsidiaries in Korea; Sony released the PlayStation 2 on February 22, 2002, Microsoft followed with the Xbox on December 23.91 (Nintendo consoles continued to be published through a Korean licensee, Daewon Culture Industry.) The Xbox was struggling about as helplessly as it did in Japan, despite a tremendous marketing effort with lots of public events,92 but Sony Computer Entertainment Korea was able to celebrate the sale of a million PlayStation 2 units on On October 16, 2004, two-and-a-half years after its introduction.93

This also meant that for the first time since 1994, there would be Korean console games again. A few companies had developed PlayStation titles in the meantime, like Unico's The Masters Fighter, Soft Action's TRL: The Rail Loaders or Deniam's Logic Pro Adventure, but they were all made exclusively for the Japanese market. The first console game of the new millennium targeted at a Korean audience was Manic Game Girl. Arriving on June 7, 2002 it was awfully late for a title on the original PlayStation, which actually had been officially released in Korea after the PlayStation 2. Developer Joycast also worked on a 3D shooting game for the PlayStation 2 called Wings, but all that remains of it is a leaked prototype.

Ecually unsuccessful were Digital Dream Studios' console projects. The game developer / animation studio had announced no less than six games for the Xbox, but unsurprisingly the company was totally in over its head with that workload. Only one of the games, the short 3D platformer Mangchi the Hammer Boy, eventually made its way out on Windows PCs. The dark and gritty Astonishia spin-off The Soulless for PlayStation 2, which featured disturbing but fascinating artwork by Limha Lekan, never went beyond the concept stages.

A few titles for the new console generations actually made it out, though. Aside from the two famous success stories of Kingdom under Fire and MagnaCarta, Axis Entertainment delivered the PlayStation 2 racing game Axel Impact in 2003, which also managed to make it westward two years later in an updated version called DT Racer. From N-Log Soft came Mystic Nights, an unique networking survival horror game where one player would secretly take the role of the monster. EXPotato ported their wacky arcade hit Come On Baby to Sony's console. Interestingly, all Korean PlayStation 2 games were published directly by Sony Computer Entertainment Korea.

The popularity of consoles never went back to the one in "eight households" of the early 1990s. Something else had changed, something that is much harder to grasp in its specifics. The social acceptance of home consoles had actually made a big step backwards in the intermediate years. When asking Koreans about why so few peoples tend to own one, the replies are similar to the explanation game designer Kim Kyongsoo gave in our interview: "PCs are in every household now since they're not mere gaming devices, but in a country that is as obsessed with education like ours, consoles that require people to invest money just to play games aren't very widespread." Now "education fever" had always been a big thing in Korea - going all the way back to premodern times, when Neoconfucian literati dominated the society. As early as 1983, the Kyunghyang Sinmun declared Korea the most education-focused country in the world.94

Yet something had changed between 1992, when almost every other kid got to own a console, and the 2000s, when even the most valiant marketing efforts could only draw a niche audience, and simply owning a console could easily get someone under suspicion of being a good-for-nothing game addict - with a computer it was at least easy to pretend needing it for other purposes.

A corner shop selling consoles and games, 1993 (photo: Game Champ)

Big successes and the call to the world

The almost complete absence of Japanese RPGs on the market from 1994 onwards left the field wide open for indigenous Korean titles to fill the void. Mantra, a publisher usually focused on ports and localizations, landed the first hit that would lead PC games sales charts, Ys 2 Special. Granted, the title based on Falcom's classic mostly got gamers convinced through its famous pedigree, and was later also one of the first games that severely enraged customers due to severe bugs and some questionable added content.

The first completely original title with the same degree of success followed soon after, Korea's first legendary title: Astonoshia Story by Sonnori. Being the first Korean game to break the 50,000 copies sales barrier,95 it made Sonnori one of the most famous names in the industry - and by association also publisher Softry, who shamelessly exploited its newly won recognition value for future, much less stellar products.

Astonishia Story also set a new trend for Korean RPGs to come: Rather than the simplified battle scenes of a Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy, it relied on a tactical combat system more akin to the Ultima series or SRPGs. The same niche was also followed by Softmax for its first RPG. The companies former games, the platformer Lychnis and the shoot-'em-up Sky and Rica, had a lot of heart and adorable pastel graphics, but not that much sales pull. The War of Genesis, however, should become the closest to a Korean equivalent to Final Fantasy both in terms of popularity and longevity - including spin-offs and mobile games, the series spans more than 10 games. Later episodes sold more than 100,000 units in Korea alone. What set the series apart from Astonishia Story's goofy slapstick and satire was an epic, serious fantasy story with a connected history over several games. Not quite as successful but still enjoying a lot of prestige with gamers were action RPGs, like Nam Inhwan's comeback Liar: Legend of the Sword II and HiCom's Corum series.

Ultimately, however, the Korean market remained much to small to turn a decent profit for more than a few surprise hits - not least because of massive piracy issues (in a survey by PC World in 1992, less than 20% of gamers obtained their software legally96). Anti-piracy campaigns could only do so much. Ads that appealed to gamers' patriotism didn't have much of an effect either, and so companies started to search for other markets to penetrate.

The industry's strongest ties lead to Taiwan, and thus most Korean game exports went to the Republic of China, returning the favor of the many Taiwanese titles that had been imported the years before. Family Production were first to place its Pee & Gity series there late in 1994, followed by Taff System's military simulation K1 Tank and many more titles. The deals weren't that delicious though: Each game only got 5,000 copies, which earned their creators 3 dollar each.97

Softmax managed to negotiate better conditions for The War of Genesis in Japan, but still only 5,000 copies were produced, whereas the PlayStation version with a promised 20,000 copies98 was never made. HiCom's Geisters, a tie-in to the first animated movie ever produced in cooperation between Japan and Korea, was even more ambitious. The publisher proudly proclaimed that a 50,000-copy PlayStation run was confirmed, and the game was part of an advertisement campaign with the slogan "Games that don't use foreign money, but earn foreign money".99 But in the end, the amount of PlayStation copies that were actually produced was exactly zero. This was the usual fate of many planned PSX ports that were announced around that time (Soft Action's Universal Force,100 Mirinae's Battle Gear,101 Softry's My Friend Koo102), but the only ones that were ever produced were some arcade ports: Deniam's Logic Pro Adventure and Unico's The Masters Fighter.

The Koreans had no better standing in the technology-obsessed Western games market: The first Korean game to make it to the US, the solid and well-programmed vertical shooter Baryon, was distributed as shareware. The best a Korean game could hope for was being picked up by some low-budget shovelware publisher: Family Production had a deal with Microforum (which also obligated them to bring the abysmal Maabus to Korea), while several of Mirinae Software's games ended up in bug-ridden, music-ripped botch jobs by JC Research. The most popular titles never even made it to the West: The War of Genesis 2 was supposed to come out in France, after the tentative Japanese publisher got Softmax in contact with the French publisher IDE Software.103 But not only did the French version never happen, the Japanese release was also dropped, leaving the single best selling Korean game from the DOS era without any localized versions at all. Dragonfly's Karma, Korea's first polygonal 3D RPG, was also left hanging after German publisher BlueByte wanted to bring it to Europe.104 It certainly wasn't for a lack of effort among Korean developers: Under the umbrella of KOGA, several developers prepared English language demos to showcase their games at the 1997 ECTS.105 Jamie System's Eryner even shipped with an English language option106 - but was never released in an English speaking country.

Eventually Korean games managed to find some respectable success in the neighboring countries in East Asia. The major export country remained the Republic of China. The niche PC game market in Japan didn't allow for big jumps most of the time, but the War of Genesis spin-off Rhapsody of Zephyr, an homage to Alexandre Dumas' novel The Count of Monte Cristo, made it to the Dreamcast and PlayStation 2. Softmax' later PlayStation 2 title MagnaCarta was significantly more successful in Japan than in its home country and sold 120,000 units in just four days.107 Kingdom Under Fire: The Crusaders by Phantagram even became a major Xbox title world-wide, but all this happened on consoles, as the PC market in Korea had already all but died down.

To be continued...

A crisis, a blizzard and the world wide web

And in the arcades?

References

1. http://www.dal.kr/col/pcadvance/pcadvance199404.html

2. http://clien.career.co.kr/cs2/bbs/board.php?bo_table=park&wr_id=402219&page=3018

3. PC Power Zine 8/1999, page 318

4. Gamespot Korea - Self Story: Trigger Soft's Jeong Musik; Kim Mukwang's memoirs mention entering a regular working schedule only in 2001, when his team Garam & Baram joined Grigon Entertainment.

5. http://blog.naver.com/PostView.nhn?blogId=yuporia2&logNo=60012339552&redirect=Dlog&widgetTypeCall=true

6. PC Power Zine 11/2000, page 212

7. Ibid, page 213

8. GameChamp 4/1993, page 39

9. GameChamp 9/1993, page not numbered

10. AmuseWorld 11/1997, page 42

11. Homepage at www.gameschool.co.kr

12. http://www.saramin.co.kr/zf_user/recruit/company-info-view/idx/4983120

13. https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:u3qmAcICVLgJ:http://kgia.or.kr/introduction/history_90.php

14. Amuse World 10/1997, page 38; ET News 5/4/1994

15. Maeil Gyeongje 2/22/1994, page 12

16. Other companies included Saem Jeonja, Gasan Jeonja, Twim, Marixon and Mirinae software for PC games, Samsung, HiCom, Gabin Mulsan, Open, Sieco, Cosmotech for consoles, as well as Dooly Multitech, Gobong Saneop and B&T as distributors; Dong-A Ilbo, 2/9/1994, page 21

17. Maeil Gyeongje 9/21/1996, page 9

18. http://news.simfile.chol.com/index.php?cmd=view&sd=19970101&ed=19981231&cat=IT&scat=IT_GEM&tc=4488&cp=&newsid=ELEC_P479080

19. Game Champ 8/1993, page 48

20. PC Champ 11/1996, page 94

21. Maeil Gyeongje 11/3/1994, page 13

22. Game Champ 11/1994, page 63

23. Hankyoreh 10/8/1996, page 11

24. Jeong Mira et al.: Eorini-wa Multimedia, 2002, page 142

25. Hankyoreh 2/20/1993, page 8

26. Dong-A Ilbo 3/1/1993, page 13

27. Maeil Gyeongje 7/24/1995, page 10

28. Dong-A Ilbo 8/13/1996, page 20

29. Amuse World 10/1996, page 50

30. PC Champ 12/1995, page 12; Maeil Gyeongje 12/15/1995, page 13

31. Amuse World 2/1997, page 18

32. http://www.seoul.co.kr//news/newsView.php?code=&id=19940812013001&keyword=%B9%CC%B8%AE%B3%BB

33. Gamechannel 11/1994, page 37

34. Hankyoreh 11/18/1994, page 12

35. Dong-A Ilbo 11/30/1994, page 21

36. Game Champ 9/1994, page 114-117

37. As Triggersoft's Jeong Musik, who got the expemption as the first employee in his company in 1998, attests in his Self Story on Gamespot Korea.

38. One example is described in Kim Mukwang's Self Story on Gamespot Korea, which mentions that team Garam & Baram member Kim Sehun leaving for a company that was in the military exemption program.

39. Dong-A Ilbo 8/1/1996, page 17.

40. http://archive.gamespy.com/amdmmog/week1/index3.shtml

41. http://www.fujitsu.com/kr/about/

42. Game World 2/1995, page 60

43. http://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2008/12/11/korea/

44. Dong-A Ilbo 10/13/1992, page 13 talks about average IBM PC systems for 2,000,000 Won, in Hankyoreh 7/4/1995, page 13 it's around 3,000,000. Check the appendix for contemporary console prices.

45. mport restrictions for the components had been an issue at first, but they were soon resolved. Game World 10/1991, page 228-229

46. Game Champ 8/1994, page 136-137. The Journal Multimedia'96 (page 55) on the other hand saw the console market shrinking from 137 billion Won in 1992 to 5,68 billion in 1993 (the year of the epilepsy hysteria), then rise again to 81.2 billion in 1994

47. Kyunghyang Shinmun 9/11/1992, page 9; There don't seem to be any statistics for the number of households in Korea in 1992; in 1995 it was roughly 14 million households, but the figure has been rapidly growing since then.

48. Dong-A Ilbo 2/3/1993, page 21 and Maeil Gyeongje 2/3/1993, page 23

49. As happened in Kyunghyang Shinmun 1/27/1993, page 23 and Kyunghyang Sinmun 1/28/1993, page 23 with various cases from 1990-1991, based on old medical records

50. Korea Newswreview 2/6/1993, page 9

51. Dong-A Ilbo 1/27/1993, page 23

52. This started when it was first reported about the incidents in the US. Kyunghyang Sinmun 1/16/1993, page 23 and Dong-A Ilbo 1/15/1993, page 23

53. Dong-A Ilbo 1/31/1993, page 18

54. Korea Newswreview 2/6/1993, page 9

55. Dong-A Ilbo 2/4/1993, page 22

56. Hankyoreh 1/29/1993, page 7

57. ET News 1/24/1994; Game Champ 8/1994, page 136-137

58. Kyunghyang Shinmun 1/27/1993, page 23

59. Game Champ 9/1993, page 52

60. Game Champ 4/1994, page 117

61. PC Power Zine 3/1999, page 162

62. PC Champ 8/1996, page 90

63. PC Champ 3/1997, page 76

64. PC Champ 2/1998, page 121

65. PC Power Zine 6/1999, page 146

66. PC Power Zine 2/1999, page 154

67. PC Power Zine 8/2000, page 171

68. It appears the developer later made the uncensored version available via download. http://blog.naver.com/PostView.nhn?blogId=dmsdn8041&logNo=70066927553&widgetTypeCall=true

69. PC Champ 7/1997, page 93. It is not established whether or not the game was ever released in Japan, though

70. Game Champ 2/1994, page not numbered

71. Game Champ 12/1992, page 25

72. Game Champ 6/1994, page 57

73. Dong-A Ilbo 12/19/1995, page 23

74. Maeil Gyeongje 9/20/1995, page 12

75. Game Champ 12/1994, page 93

76. Maeil Gyeongje 9/20/1995, page 12

77. Multimedia '96, page 56

78. Game Champ 9/1994, page 57

79. Multimedia '96, page 58

80. Gamepia 1/1997, page 90

81. Multimedia '96, page 58

82. Gamepia 7/1996, page 177

83. Multimedia '96, page 58

84. Maeil Gyeongje 5/26/1995, page 12

85. http://news.simfile.chol.com/index.php?%20%20cmd=view&sd=19970101&ed=19981231&cat=IT&scat=IT_GEM&tc=6503&cp=&newsid=ELEC_P484051

86. Amuseworld 11/1999, page 116

87. http://www.gamechosun.co.kr/article/view.php?no=988

88. http://news.inews24.com/php/news_view.php?g_menu=022600&g_serial=14490

89. http://www.gameshot.net/common/con_view.php?code=AA00044501

90. http://contents.archives.go.kr/next/content/listSubjectDescription.do?id=003611

91. http://game.donga.com/13946/

92. Only 50,000 units were sold until the end of 2003, though sales are said to have experienced a boost after Xbox Live became available. http://www.gameshot.net/common/con_view.php?code=AC401338ac8d91a

93. http://www.scek.co.kr/about/about_scek.sce

94. Kyunghyang Sinmun 1/13/1983, page 11

95. Kyunghyang Sinmun 10/27/1998, page 25

96. Among 80 questioned kids, 52.5% copied their games from friends, 13.75% bought cheap pirate copies in shady computer stores, 15% downloaded from BBS. 17.5% bought legit copies themselves, while only 1.25% got them from their paraents. PC World 8/1992, page 57

97. Dong-A Ilbo, 11/5/1996, page 33

98. PC Champ 4/1996, page 93

99. Advertisement in Gamepia 2/1998

100. PC Champ 2/1996, page 106

101. PC Champ 5/1997, page 100

102. PC Champ 7/1997, page 91

103. PC Champ 10/1996, page 84

104. PC Champ 11/1997, page 118

105. Mirinae with Full Metal Jacket and Softry with Record of Arman's War, for example. PC Champ 8/1997, page 102

106. PC Champ 11/1997, page 120

107. Gameshot 11/19/2004

Other Sources

The International Arcade Museum Invaluable source of information on old coin-op arcade games

The Korean Game Ratings Board Release information from around 1993 onwards

Ruliweb Big gaming "Cafe" (Korean style message board) with tons of anecdotal information

Photos from Maeil Gyeongje, Dong-A Ilbo, Computer Study, MyCom, Game World, Game Champ, AmuseWorld, PC World and Gamedonga