|

Sega Consumer History (セガ・コンシューマー・ヒストリ)

Author: Famitsu Books

Publisher: Enterbrain

Date: February 2002

Pages: 306

Language: Japanese

Review: derboo

Sega Consumer History and Sega Arcade History are a pair of simultaneously-published books on Nintendo's first challenger to the Japanese console market, put out by the Famitsu DC staff. Consumer History is the more bulky of the two, covering all of SEGA's end user-targeted hardware from the SG-1000 to the various 1st party Dreamcast peripherals. The cover also advertises "and over 2434 Software," although the book only contains some 450 short introductions to games. And those are really short; one paragraph only per game, the title screen and one additional screenshot (the strict format becomes kinda amusing at Warp's Real Sound entry (the infamous graphicless game), which only shows two pitch black screens). The number 2434 simply means the complete catalog of games released in Japan for Sega hardware, which is listed in a table as an appendix.

The selection of titles introduced has somewhat of a bias towards in-house SEGA titles, and only really cares about games released in Japan, which is a huge bummer especially for Master System fans, where even many first party titles were produced exclusively for the Western markets, especially PAL territories. Some&mash;like the 8-bit version of Sonic The Hedgehog—are covered for the Game Gear, but once again only those released in Japan.

Sega Consumer History has more to offer than just game introductions, though. You get a sort of time table each for both original games and arcade ports, where every console is assossiated with the arcade hardware(s) the ports were usually based on, and every console's chapter opens with lots of photos of the actual hardware from all angles, including standard gamepads, technical specs, description of the available connections. There are a few pages of the system's career on the market, examples of the different package design templates (for Japan, once again) and comments by Hideki Sato, SEGA's hardware engineer No. 1, who also gives an introductory 5-page interview at the beginning. Thanks to his input, this is one of the most technical books on mainstream game consoles.

But the software creators are also dragged out of their cubicles to be "The Witness of History." Yuji Naka (Sonic Team), Noriyoshi Ohba (Bare Knuckle series, OverWorks studio) and Rieko Kodama (Phantasy Star, Skies of Arcadia) are only some of the more famous names, and even voices from some of the 3rd parties who particularly supported SEGA consoles (Compile, Westone, Game Arts, Climax, Camelot and Treasure) are given their time. But for a Japanese company, SEGA is very generous with retro developer interviews in general.

Interspersed miscellaneous history bits are brief but extremely interesting, there's even half a page specifically describing the emergence of adult software for the Saturn. Those pages are also the rare instances where it branches out into overseas (=North American) territory, which, aside from the dilligent listing of every North American hardware variant is spotty at best. TecToy, for example, the famous Brazilian licensee for Sega hardware, doesn't seem to even be mentioned at all.

The totally Japan-centered viewpoint is almost the book's only weakness though, maybe aside from the small format, which makes it a bit strenuous on the eyes to make out some of the photos and most of the screenshots. And of course, for Western readers, the fact that it's all in Japanese. But there's still a lot of usable data and tons of images, even if you've got no access to the interviews and history texts.

|

|

|

Sega Arcade History (セガ・アーケード・ヒストリ)

Author: Famitsu Books

Publisher: Enterbrain

Date: February 2002

Pages: 209

Language: Japanese

Review: derboo

Sega Arcade History is noticably thinner than the other book, and lacks the fuzzy and melancholic feeling of conclusiveness, since of course Sega kept producing new arcade machines afterwards. On the other hand it can be more thorough, as it "only" features Sega's own output—432 games as advertised on the cover. With the exception of highlights like Space Harrier, Virtua Fighter or Derby Owners Club (don't forget, it's Japan), the introductions are just as brief as Consumer's, but all custom cabinets, starting from their early '70s stuff, are shown in photographs. The only problem: Most of them are tiny, the same goes for the small selection of vintage flyer art at the end of the book.

Interviews are more secluded as well: The book opens with words from some really old '60s Sega veterans no one hardly anyone will know/remember, but later representatives from most of the former AM teams have their say. Old legends like Yu Suzuki talk about the beginnings of their careers just like still rising stars such as Hisao Oguchi (Hitmaker/AM3, now one of the big bosses at Sega and Sega-Sammy Holdings), Toshihiro Nagoshi (Amusement Vision/AM4, now producer of the Yakuza games), and even some lesser known technicians and voices from the non-vide game amusement machine departments.

Nice features like a hardware timeline (which visualizes how the Model 1 outlived the much older System 16 only by a month, for example) and a look at some of their "attraction" machines (hydraulic CGI-3D-rides and the like) round up the package, but it still feels a bit barebones compared to the Consumer History, and the images really suffer from the small format.

|

|

|

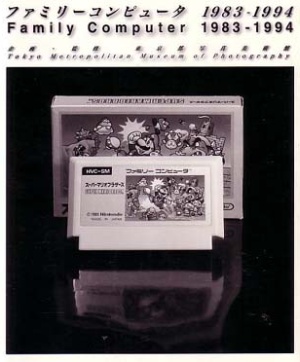

Family Computer 1983-1994 (ファミリーコンピュータ 1983-1994)

Author: Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

Publisher: Ohta Publishing

Date: December 2003

Pages: approx. 200

Language: Japanese/English

Review: John Szczepaniak

There have been several attempts at comprehensive books focusing on the games of the Famicom/NES. David Sheff's Game Over doesn't count since it's mainly about the business. There was a two volume encyclopaedia-style book in Japan (Fami-Complete), and there's also La Bible NES, written and published by the French. Both of these examples, as fine as they may be, are sadly not available in English and are therefore of limited use to those not proficient in either language. There was an American attempt to catalogue all the games with screens and reviews, by a gentleman known online as ManekiNeko, but without publisher backing he put it online. The resulting A-Z entries were brief, uninteresting and lacked insider insight. Without question, the best book for any fan of the Famicom or NES is still Family Computer 1983-1994 by the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography and Ohta Publishing, in conjunction with the Level-X exhibit to celebrate the Famicom's 20th anniversary.

It is the perfect book. For a start it features interviews with several major Japanese developers, regarding either their work on Famicom games or, if they worked on rival hardware, their views on the era. It features Shigeru Miyamoto, Shigesato Itoi, Yuji Horii, Kouichi Nakamura, Satoshi Tajiri, Ken Sugimori, Hideo Kojima, and Yuji Naka. Their answers are candid, very detailed and—best of all—available in English alongside the original Japanese. In fact everything in the book is available in both Japanese and English. The translations aren't perfect, but that's not a deal breaker. Everything is perfectly understandable, and it makes for more charming reading than something done by committee and filtered through corporate PR.

Additionally it features full-page examinations for major releases and quarter-page bites for other interesting titles (see to the right)—these are more than mere reviews though, and contain nuggets of insight regarding who worked on them and how they resonated with the public. There are photographs of everything else. This is important to note: every single Japanese Famicom game ever released has been photographed and includes an entry detailing its name in both Japanese and English, publisher and developer, precise release date, and launch price. It's safe to say that the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum got their facts right, which makes this tome an extremely valuable resource. The addition of the reviews also offers great insight into the atmosphere of the time and a snapshot of Japanese tastes. There are the obvious contenders (Mario, Dragon Quest, etc), and some US favoured titles are not covered in-depth, but significantly it contains detailed opinions on games unique to Japan which you'd otherwise never find insight on—such as an intra-office simulator fronted by an actual Japanese politician. These entries might not resonate with hardened Zelda fans, but it paints a fascinating view of the foundation of Japan's entire industry.

It's clear that a tremendous love for the subject matter was had by those who produced this extremely professional book, and the fact that they had the foresight to translate it into English is miraculous. The praise given here might seem a tad over-zealous, but if you're even remotely interested in either the Famicom or the NES, then there is no way you could be disappointed by this book.

Browse on Amazon.co.jp

|

|

|

The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual

Author: David Thomas, Kyle Orland and Scott Steinberg

Publisher: IGJA / Games Press

Date: July 2007

Pages: 100

ISBN: 978-1-4303-1305-2

Review: derboo

"A necessary part of moving game journalism, and games, to the next level." With those words by Dean Takahashi the The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual advertises itself, and the cause seems noble and desirable; each step towards a consistent use of names and termini across the thousands of web publications and blogs that deal with video games—predominantly or peripherally—has to bring a great deal of relief for anyone who ever agonized between "cut scenes," "cutscenes" or "cut-scenes." The Videoga—there's already the first problem: Videogame, written as a single word. The issue is even adressed in the introduction, "but someone had to make a choice and draw a proverbial line in the sand. So that's what we did, because that's what journalists and editors have to do every day - make tough decisions." Well, frankly, that was a bad decision—by the book's very own standard, which puts up the following four statutes for those "tough decisions."

1) Ease of comprehension for a general audience.

2) Common usage and accuracy.

3) Convenience, with respect to writer use/remembrance.

4) Official styling, as preferred by game developers and publishers.

The only guideline that applies to this choice is number 2. Championing "videogame" (58,000,000 hits on google) over the much more accepted and widely used "video game" (408,000,000 hits on google, refered to as such in the Oxford English Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia) only puts the authors under the suspicion of a petty attempt to promote their minority preferences through the publication, rather than actually caring for an improvement of games journalism. The main part, which is essentially a short dictionary for gaming-specific terms, also shows some weird omissions: Apparently Thomas, Orland and Steinberg complete all their games in one single session, as terms used for storing game status are alien to them: No savegame (save game? save-game?), quicksave, autosave, not even passwords are found in the listing. Then there are seemingly arbitrary taboos on certain abbreviations: "Sega Master System (SMS) Do not shorten to Master System." Why not? Are there any other well-known Master Systems it needs distinction from? Where's the "may be shortened after the first use"-clause that can be found in many other entries?

The last quote was already from one of the appendices, which provide lists of official spellings for a number of game consoles and operating systems, sales figures for some important systems and common video game genres. These are the most useful in the book, although they leave writers alone as soon as they stray to far away from the mainstream. Though not as much as the "brief History of videogames," which only contains the most essential milestones every video game writer should have memorized (aside from those that may or may not be incorrect). The lists of notable video game characters, companies, personalities and titles finally are so damn short they might just as well not be there.

Finally, an afterword that praises pretentious rambling about the meaning of life as the highest form of criticism, and a list of article URLs with an unproportional prominence of "new games journalism" leaves no doubt about what the cover quote meant by "moving game journalism to the next level," further alienating readers/writers that might not identify with this particular niche.

All the doubts about the book's integrity aside, the most important question remains: Is it useful for my publication/website/blog? It is, at least by saving the first steps to what can eventually become a complete compendium of important terms with your own additions and alterations appended to it. Will it move game journalism to the next level? Aside from actively trying to worsen the confusion about "video games" and "videogames" by promoting the separatist spelling that should really be eliminated, it actually might if it can bring everyone to care about consistency within their own editorial body.

Update 01/28/2013: The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual has since been made available as a free e-book. Be sure to check out the official homepage when interested.

Visit the homepage

|

|

|

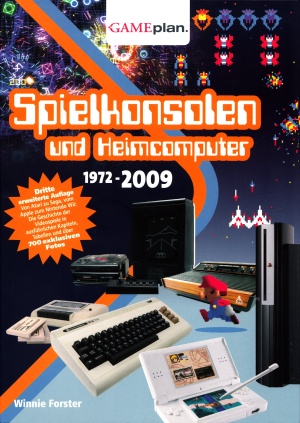

Spielkonsolen und Heimcomputer 1972-2009

Author: Winnie Forster

Publisher: Gameplan

Date: June 2009 [first edition 2002]

Pages: 240

Language: German

Review: derboo

Winnie Forster's Spielkonsolen und Heimcomputer is hands down the most complete compendium of gaming machines you'll find in printed form. It covers not only dedicated consoles, but also many home computers that were not designed for gaming, but of course became thoroughly "abused" for the "pastime" nonetheless. Each entry comes with the most important data for a device; units sold, number of available games, storage media, release and discontinuation dates, as well as a somewhat untransparent 5-star evaluation of the overall variety and quality of the games library. The short to medium-sized rundown of the system's history, important games and description of the hardware is composed in the dry writing of an encyclopedia, which is what this ultimately strives to be. Neat is the table at the end of most entries, which lists updates and variations with their individual peculiarities.

Inside the scope of the compendium are home consoles, home computers and dedicated gaming handhelds, whereas arcade machines, mobile phones with game capabilities (with the exception of the N-Gage) and non-programmable single game / compilation devices like the '70s Pong consoles or LCD handhelds are not covered in detail, but briefly taken account for in the history 2-pagers, that are interspersed in between. There's even a neat overview for the different magnetic, optical and electronic storage media games are and used to be played on, and also the appendix which compares technical specs of same-generation machines in a handy table.

What more could one wish for? The book being in a language one can read, for example. The second edition, dubbed Game.Machines, was actually published in English in 2005, but it is out of print, with used copies usually going for very steep prices. But even the listing price for the current edition with EUR27.80 isn't exactly cheap for a 200-something pages paperback, since Gameplan is basically just Winnie Forster's do-it-yourself publishing company and books in Germany are generally quite expensive. It is not too difficult to make out what each field of data means whithout being able to read much German, but reading text body requires decent language proficiency. The new one is mostly an update with some errors fixed and the new consoles released since 2005 included, though, so you're not missing too much if you should be able to track down a copy of the English edition. The first edition, released in 2002, on the other hand, is about a hundred pages shorter, still with significant gaps.

But even in its 3rd edition, Spielkonsolen und Heimcomputer is not quite perfect. For overseas readers, the eurocentric view becomes immediately obvious when they try to find the Magnavox Odyssey II, which is only listed as the Philips G7000, with a passing mention of its origin in the text body. Then there are full entries for the X68000 and FM-Towns (both 2 pages), while Japan's 16-bit home computer No. 1 is delegated to the far end of the book as a 2-paragraph stub, alongside obscurities like the Dragon 32 and Gizmondo. Of course one can't hope for every single mega-obscure device to find its way into the book, either, so those interested in Soviet home computers or the Taiwanese 16-bit console Super A'can have to turn to the internet for their fix.

A few other decisions seem dubious no matter which way you look at them. Six pages for the GBA? Is the platform really as interesting or important as the MSX or the PS2? And can the Mark III and Master System really be filed as "variations" of Sega's SG-1000? Because they're backwards compatible? Then why is the PS2 not a variation of the PSX? Other than these minor flaws in composition, of course it's quite impossible to compile that much data without a bunch of errors slipping in, which the official homepage has a sizeable list of corrections for.

Gameplan also carries several other, mostly encyclopedic books: Joysticks looks exclusively at various game controllers on 144 pages, Lexikon der Computer- und Video-Spielmacher is a reference of companies and personalities, and probably the least penetrable for non-German speakers, but only because Volkscomputer is just a slightly expanded translation of Commodore: A Company on the Edge by Brian Bagnall.

|

|

|